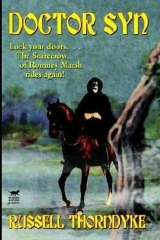

Текст книги "A Smuggler Tale of the Romney Marsh"

Автор книги: Russell Thorndike

Жанр:

Исторические приключения

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 8 (всего у книги 15 страниц)

Chapter 22

A Curious Breakfast Party

During the meal Jerry took good stock of both men. The captains manner was sullen and grumpy. He was turning things over in his mind that he was incapable of solvingthings altogether out of his ken. Doctor Syn, on the other hand, seemed eager to discuss all these curious events, but underlying his interesting, polished, quiet conversation there smouldered a nameless fear which now and then burst into flames of enthusiastic furyfury against the captains apparent inactivity in taking measures to find and capture the mysterious mulatto. But he never went too far, never said anything that his tact

212

could not smooth over; in fact, he was at great pains not to quarrel with the captain, like the squire had done, for the captain was evidently very sensitive within that rough exterior, as he had shown by not attempting to patch up his quarrel with the squire.

So Jerry watched them as they breakfasted in the sanded parlour of the Ship, keeping in the room all he could and dreading to be dismissed.

Presently the captain turned to him and inquired whether he had breakfasted. Jerry replied that he certainly had had a snack or two, but that broiled fish always did go down very pleasant with bread and butter and fresh milk, and accepted with alacrity the invitation from the captain to bring a chair and help himself.

The captain got up, filled a pipe and lit it, and the Doctor did the same; then both men pushed their plates to the centre of the table, leaning their elbows on the cleared space; and Jerry in the centre, for all the world like a judge of some

213

quaint game of skill, watched the opponents as they drew deliberately at their pipes, sending preliminary battle clouds across the table before the real tussle beganaye, a fight of brains, each one desirous of ascertaining how much the other knew or guessed about these strange events, but each very fearful of betraying what he guessed. So Jerry watched them, feeling certain that a battle was imminent, wondering upon what side he would be called to fight, and what the end of it all would be; but with all his watching and wondering he didnt forget to eat, and eat heartily, too, for Jerrys maxim was, Eat when you can, and only think when youve got to.

The captain spoke first.

Doctor Syn, you heard me say at that inquiry yesterday that I was no strategist, that I was only a fighter.

I did, returned the cleric.

214

I know everything inside, outside, and around-about a ship, but I dont know much else, and certainly nothing else thoroughly, so to speak. But I have seen other things in my time, for all that, just as any one who travels is bound to see things, and, just as any one else that travels, I have remembered a few things outside my business, just a few; the rest Ive forgotten. Now youre different from that, for youre a scholar and have travelled widely, too, and a man who can use his book knowledge with what he comes in contact with in the world is the sort of man who might perhaps explain whats bothering me at the present moment, for I am dense; you are not.

What is bothering you, Captain? Of course something to do with these murders that are uppermost in our minds?

Something, I dare say, replied the captain slowly, weighing his every word, but, on the other hand, maybe its nothing. I cant connect the two things myself, and yet Ive a feeling that I ought to be able to. Ive tried,

215

though, tried hard, been trying all through breakfast, and it worries me, because, as a man of action, thinking always does worry me sorely. You may laugh at what I am going to tell you; if you do I shant take offence, because its precisely what I should have done had any one told me about what Im going to tell you, something thatthe captain hesitated, speaking as if he longed to keep silent; speaking as if afraid of being disbelievedsomethingwell, Ill tell you that it sounds ridiculous on the face of it, but something whichwell, which I saw myself.

Tell me, said the cleric, leaning farther forward over the table.

The captain sat up rigid in his chair, took his pipe from between his lips, and spoke as if repeating a lesson that he didnt understand.

Once in a Cuban town, in a little Cuban towncant remember the precise longitude and latitudebut thats no matter, and I cant even remember the

216

name of the town or what I was doing there exactly, but that has no odds on the

story.

Go on, said the cleric.

Well, in this little Cuban town I saw an old priest die. He was as dead as this table, you understand, the doctor said so, and I knew it. Well, imagine my horror when half an hour after death this old man arose, entered the next hut, and deliberately, brutally, and carefully stabbed a sleeping child to death.

The Doctor said nothing, but just looked at the captain.

Jerry stopped eating and looked at Doctor Syn. He was pale, very pale.

Then the captain leaned over the table and continued speaking, but not like a lesson, for there was a thrill in his voice that carried conviction, so Jerry looked at him.

217

I found out afterward that the dead fellow had borne a lifelong grudge against his neighbour. The revenge that he had somehow failed to get during his lifetime he accomplished after his death. It was devilish curious.

It was a devilish trick, explained the Doctor. The fellow was feigning death to a good purposenamely, to put his neighbour off his guard. He was not really dead. It would be against all laws of naturewhy, of course it would for a man to arise and walk and commit a foul murder half an hour after his decease! Nonsense, fanciful nonsense!

Against the laws of nature, Ill allow, went on the captain, as if he had fully expected that his story would be disbelieved, but if youll excuse me saying so, who are you, Doctor Syn, and for the matter of that who am I, to say what the laws of nature are, or to dare to affirm just how far they extend? For my own part, I should prefer to question my own ignorance rather than the laws of nature.

218

But in what way do you hint at a connection between this story and our present trouble in the village owing to this murdering-mad seaman?

Why, just this, went on the captain deliberately. When you caught sight of this same murdering-mad seamanyou remember, last night, outside the barnI noticed that you took cold all of a sudden; you got the shivers.

Marsh aguemarsh ague, put in the cleric quickly. Get it often in this place. Poor old Sennacherib Pepper used to tell me that it was the result of malaria I once had badly in Charleston, Carolina; nearly lost my life with it. Mosquito poisoning which brought on raging malaria. I dare say he was right: Im a frequent sufferer. As soon as the mists rise from the Marsh I get the shivers.

Ah, then there falls one of my points to the ground. Still I have another ready. Suppose we grant that your attack of ague had nothing to do with your sudden meeting with this man.

219

Of course it hadnt, muttered the Doctor. Absurd!

Very well, then, did you notice that the entire weight of the barrel was carried by Bill Spiker, the gunner?

No, said the Doctor, I didnt notice that.

No more did Bill Spiker, said the captain; you can lay to that, or he would have soon raised objections; but I did notice it, because its my business to note which of my men work hardest, you understand; for in cases of preferment I have to give my opinion.

I dont see what that has to do with the case, said the Doctor. Its a common enough complaint to find a man shirking work.

Not when the man who shirks is an enthusiastic and willing worker. Thats what made me wonder in the first place, and Ive now come to the conclusion that whenever the mulatto was ordered to work alonealone, mind you, without the help of the other seamenwhy, he could accomplish anything, but

220

when he was working with anybody, he seemed, in spite of himself, to become singularly useless.

You call yourself dense, Captain, and you affirm that I am not; but you seem to have a keener perception of the abstruse and vague than I have, or can even follow.

You will be able to follow me in a moment, said the captain humbly. I fear it is the poor way in which I am getting to the point; but I have to tell things in my own way, not being given to talk much.

Go on, then, in your own way, said the cleric.

I then recollected that in my short acquaintance with this mulatto I never remember to have seen him in actual contact with any one, or any thing. And I also recollect a strong tendency among the men to avoid himin fact, to keep out of any personal contact with him.

221

Natural enough, explained the cleric. It is the white mans antipathy toward a native. Perfectly natural.

Perfectly, agreed Captain Collyer. And I think we may add the Englishmans antipathy toward the uncanny and mysterious.

I dare say, said Doctor Syn.

I am sure of it, went on the captain. Indeed, I went so far as to ask the bosun, who has had most dealings with the fellow, whether he had ever touched him.

Touched him? What do you mean? asked the parson, who began dimly to see what the other was driving at.

Touched, touched him, repeated the captain with emphasis. The bosun told me No and that he wouldnt care about it, for he considered that a weird-looking coveIll use his precise way of expressing itthat a weird-looking cove with a face like a dead un, what never took food nor drink to his

222

knowledge, werent the sort of cove that a respectable seaman wanted to touch.

Jerry looked at the Doctor. He was as white as the snowy tablecloth before him. Yet he still feigned not to quite follow the captains reasoning.

And now, asked the captain, mad as it sounds, do you see any connection between the two cases? Its plain to any traveller or reader of travel books that some of these foreign rascals, especially the priests, possess strange, weird gifts that the white mans brain runs short of, and I want to know if you see any connection between the two cases.

Doctor Syns had was trembling, so much so that the long clay pipe stem snapped between his finger and thumb. Neither seemed to notice this, though the lighted ashes had fallen out of the bowl upon the tablecloth and had burned innumerable holes in it before going out.

223

Do you see any connection, Doctor Syn? asked the captain, leaning right over the table and bringing his face close to the cleric.

Doctor Syn did not answer.

The captain repeated the sentence once morewith all the emphasis and force that he could put into his compelling voice:

Any connection between the Cuban priest who was able to commit deliberate murder after death by controlling the enormous will power of his revenge upon that one definite object? Do you see any connection, I say, between that man and a man who was marooned upon a coral reef in the Southern Pacific being able to follow his murderer across the world in the beastly hulk of his dead self? I dont understand it, nor do you, perhaps, but I fancy that I see the semblance of a connection, and what I want to know is, can you?

224

Then Doctor Syn did a surprising thing: He slowly raised his face to the level of the captains, then brought his eyes to meet the captains gaze, and then, drawing his lips apart, laying his white teeth bare, he slowly drew over his face, from the very depths of his soul, it seemed, a smilea fixed smile that steadily beamed all over him for at least a quarter of a minute before he said:

You most remarkable man! A Kings captain, eh? I vow you have mistaken your calling. And he deliberately and with the flat of his white hand patted the captains rough cheek, patted it as though the captain were a child being petted or a puppy being teased.

What the thunder do you mean? roared the infuriated officer, by calling? Mistake my calling?

Your profession, said Doctor Syn, calmly putting on his cloak and hat.

What would you have me then? cried the seaman.

225

I wouldnt have you any other than what you are, sir, replied Doctor Syn, with his hand on the door latcha thoroughly entertaining and vastly amusing old seadog, mahogany as a dinner wagon, and loaded with so many fancies as to be creaking near the breaking point.

The captain was so taken aback with the extraordinary manner of the Doctor that he could only look and gasp. Doctor Syn, perfectly at ease, opened the door.

I wonder? he said in a low voice, almost tenderly, Jerry thought.

The captain, with a great effort, managed to ejaculate, What?

Why your mother sent you to sea, for as an apothecaryan apothecary aye, yes, indeed, what a magnificent analyzing apothecary the world has missed in you, sir. And to the captains amazement and Jerrys astonishment the vicar went out, closing the door behind him.

226

The captain could do nothing but stare at the closed door, while Jerry, perceiving nothing entertaining in that, stared at the captain, who suddenly exploded out in his great sea voice:

An apothecary, an analyzing apothecary! What in the devils name does he mean by that?

Jerry still looked at the captain. Certainly he had never beheld any one more unlike an apothecary. By the widest stretch of his imagination he could not picture the captain mixing drugs or making experiments.

Its my opinion he said, and then hesitated.

Yes? thundered the captain, with an eagerness that seemed to welcome any opinion.

well, its my opinion, sir, that Doctor Syn is off his headmad, sir. And its my opinion, potboy, said the captain, as if he valued his own opinion as highly as Jerry Jerks, its my opinion that hes nothing of the kind.

227

Hes feigning madness. He had to do something that he knew would take my breath away for the moment, knowing me to be dense, and he succeeded, for if any man was unqualified to be an apothecary, Im the fellow. An analyzing apothecary!

Then the captain sat down in the armchair and laughed till the tears rolled down his cheeks, and Jerry was obliged to join in, though he didnt know what he was laughing at. At length he stopped and became most suddenly grave. Getting up, he placed his hands on Jerrys shoulders.

Look here, potboy, he said, you and I have common secrets that I know. What the devil you were doing out on the Marsh the night before last I dont know, but that you saw the schoolmaster kill Pepper I do know.

You know? cried Jerk, utterly astonished. Then Doctor Syn must have told you, for I never breathed a word.

228

I know all about it, my boy, because I was hiding in the same dyke as you. Now see here, from what Ive seen of you, I imagine you can be relied upon. Well pluck a leaf out of that parsons book. Well find out his mystery. Well find out the whole mystery of this damned Marsh, and as to being apothecaries, why, damme, so we will. Well take him at his word.

And be apothecaries, sir? asked Jerry, more puzzled now than ever.

Yes, cried the captain, slapping his great hands up and down upon Jerrys shoulders. Apothecaries make experiments, dont they?

I dare say they do, sir, replied Jerk.

Well, so will we, my lad, went on the captain, as happy as a sand boy. Well set a trap for all this mystery to walk into. Well set a big trap, my lad big enough to hold all the murderers and mulattoes on the Marsh, the demon riders as well, and certainly not forgetting the coffins in Mippss shop nor the bottles of Alsace Lorraine beneath this floor. Well catch the lot, my boy, and

229

analyze em. Yes, damn em! well analyze em, inside and outside, by night and by day, give em to Jack Ketchto old Jack Ketch, wholl hang em up to dry. Not a word, my boy, to any one; not a word. Heres a guinea bit to hold your tongue; and look to hear from me before the days out, for I shall want your help to-morrow night.

And the captain was gone. Literally rushed out of the door he had, leaving Jerk alone in a whirl.

Well, he said to himself, if a man ever deserved a third breakfast, Im the one, and here goes; for both of these fellows is stark, staring mad, though its wonderful the way they all seems to take to me.

And thrusting the precious guinea bit into his pocket, Jerk again vigorously attacked the victuals.

230

Chapter 23

A Young Recruit

Talk about an ealthy child, and there he is, said Mrs. Waggetts, entering the sanded parlour with Sexton Mipps. And eat; nothing like eating to increase your fat, is there, Mister Mipps? But, there, I suppose you never had no fat on you to speak of, cos if ever a man was one of Pharaohs lean kine, you was. Its hard work wots kept me thin, Missus Waggetts, replied the sinister sexton; hard work and scheming; and a little of both would do our young Jerry here no harm.

231

As to work, replied Jerry, gulping down more food, there aint been no complaints against me, I believes, Missus Waggetts?

Certainly not, Jerry, my boy, responded that lady affably.

Thats good, said Jerk, and then turning to the sexton he added: And as to scheming, Mister Sexton, how do you know I dont scheme? Some folks are so took up with their own schemes that praps they dont get time to notice wot others are a-doin. I has lots of schemes, I has. I thinks about em by day, I does, and dreams of em at night.

And they gives you a rare knack of puttin away Missus Waggetts victuals, Im a-noticin, dryly remarked the sexton.

Lor, Im sure hes heartily welcome to anything Ive got, returned the landlady. It fair cheers me up to see him eat well, and itll be a fine man hell be making in a year or so.

232

Aye, that I will, cried young Jerk; and when Im a hangman I aint agoin to forget my old friend. Ill come along from the town every Sunday, I will, and well go and hear Parson Syn preach just the same as we does now, and Mister Mipps will show us into the pew, and everybody will turn round and stare at us and say: Why, there goes hangman Jerk! Then well come back and have a bite of supper together, that is providing I dont have to sup with the squire at the Court House.

That ud be likely, interrupted Mipps.

And, after weve had supper, Ill tell you stories about horrible sights Ive seen in the week, and terrible things Ive done, and itll go hard with Sexton Mipps to keep even with me with weird yarnin, I tells you.

Ha! ha! chuckled Mipps. Strike me dead and knock me up slipshod in a buckrum coffin, if the man Jerry Jerk dont please me. Look at him, Missus Waggetts. Will you please do me the favour of lookin at him hard, though

233

dont let it put you off your feed, Jerry. Why, at your age I had just such notions as youve got, but then I never had your advantages. Why, at thirteen years of age I was as growed up in my fancies as this Jerk. Sweetmeats to devil, eh, Jerry? for its some who grows above such garbage from their first rocking in the cradle. This Jerry Jerk is a man; why, bless you, hes more a man than lots of em what thinks they be. Aye, more a man than some of em wots a-doin mans work.

Thats so, said Mrs. Waggetts, enthusiastically backing the sexton up. And dont you forget that he owns a bit of land on the Marsh, and so hes a Marshman proper.

I doesnt forget it, said Mipps, and Ive been tellin certain folk wot had, how things were goin with Hangman Jerk, and Ive made em see that although only a child in regard to age, he aint no child in his deeds, and so they agreed with me, Missus Waggetts, that it ud be unjust not to let him have

234

full Marshmans privileges; and Ill go bail that Jerk wont disgrace me by not

livin up to them privileges.

Praps I wont, Mister Sexton, when I knows what them privileges are.

You listen and Ill tell you, answered the sexton.

And listen well, Jerry, added Mrs. Waggetts, for what Mister Mipps is agoin to say will like as not be the makin of you.

I will listen most certainly, replied Jerk, so soon as Mister Mipps gets on with it. Im all agog to listen, but theres no use in listenin afore he begins, is there now?

Jerry, said the sexton, youre just one after my own heart. You ought to have lived in my days, when I was a lad. Gone to sea and got amongst the interestin gentlemen like I did. Aye, they was interestin. And reckless they was, too. They was roughnone rougher; but I dont grudge em all the kicks they give me. Why, it made a man o me, young Jerk. I tell you, Master Jerry,

235

that bad as them sea adventurers was, and bad they wasmy eyeyes, buccaneers, pirates, and all the rest of itbut bad as they was they did some good, for they made a man o me, Jerry. I should never have been the sort o man I is now if them ruffians hadnt kindly knocked the nonsense out o me.

Shouldnt you, though? said Jerry.

Never, never! said the sexton with conviction. But mind you, he went on, you has advantages wot I never had. I had to learn all the tricks o my trade, and I had to buy my experience. There was no kind friend to teach me my tricks o trade, no benevolent old cove wot ud pay for my experience. No, I had to buy and learn for myself, but, my stars and garters! afore theyd done with me I had em all scared o me. Even England hisself didnt a-relish my tantrums; and when I was in a regular blinder, why, I solemnly believes he was scared froze o me. There was only one man my superior in all the time I sailed them golden seas, and that man was Clegg hisself. I served on his ship, you

236

know, Jerk, I was carpenter, master carpenter, mind you, to Clegg hisselfto no less a man than Clegg. And on Cleggs own ship it were, too. She was called the Imogene. I never knew why she was called so. It sounds a high fiddaddley sort o name for a pirate ship, but then Clegg was a regular gentleman in his tastes. Why, I remember him sittin so peaceful on the roundhouse roof one day a-readin of Virgiland not in the vulgar tongue, neither. He was a-readin it in the foreign language wot it was first wrote in, so he told me. And you couldnt somehow get hold o the fact that that benign-lookin cove wot was sittin there so peaceful a-readin learned books had maybe half an hour before strung up a mutineer to the yardarms or made some wealthy fat merchant walk the dirty plank. No, he was a rummun, and no mistake, was that damned old pirate Clegg. But Id pull my forelock, supposing I had one, all day long to old Clegg, even were I the Archbishop of Canterbury and he only an out-at-heel seadog. Now with England it was different, as I told you, though Ill own he

237

could beat the devil hisself for blasphemy when he was put out. But I wasnt afraid o him; he was one you could size up like. But Cleggoh, he was different. Show me the man wot could size up Clegg, and Id make him Leveller of Romney Marsh, aye, King of England, supposin I had the power. There was only one man wot I ever seed wot made Clegg turn a hair, and that was a rascally Cuban priest, but then he had devil powers, he had. Ugh! And the sexton relapsed into silence. His listeners watched him, and, watching, they saw him shiver. What old scene of horror was flashing before that curious little mans minds eye? Ah, who could tell? No living body, for the crew of the Imogene had all died violent deaths one after another in different lands, and since Clegg was hanged at Rye, why, Mipps was the only veteran left of that historical ship of crime, the Imogene.

238

Pray get on with the business in hand, Mister Mipps, said Mrs. Waggetts, for though I declare I could a-listen to you a-philosophizin and a-moralizin all day long, young Jerk is all agog. Aint you, Jerry?

Thats so, replied young Jerk. Please get on, Mister Sexton.

I will, said Mr. Mipps. You may wonder now, Jerry Jerk, how it has been possible for a swaggerin adventurer like I be, or rather was at one time, when I was a handsome, fine standin young fellow aboard the ImogeneI say you may fall to wonderin how I come to be a sexton and to live the dull, dreary life of a humdrum villager. Well, Ill tell you now straight out, man to man, and when Ive told you, why, youll understand all the mystery wot Im a-gettin at. The sexton smote his hand upon the table so that all the breakfast dishes jumped into different positions on the table, and the two words he said as his fist crashed down were these: I couldnt!

239

Couldnt what? asked Jerk, whose anxiety for the breakfast dishes safety had driven the context of the sextons speech from his mind.

Couldnt live a humdrum life after the high jinks I had at sea.

But you did, Mister Sexton, and, whats more, youre a-doin it now, replied young Jerk with some show of sarcasm.

And very prettily you can act, cant you, Hangman Jerk? said Mr. Mipps, winking. I declare youre a past-master in the way of pretendin. Well, pretendin alls very well, but its often plain-spoken truth wot serves as a safer weapon for roguish fellows, and its plain-spoken truth Im a-goin to use to you, believin in my heart that if ever there was a roguish fellow livin, and one after my old heart, why, Hangman Jerk is that fellow.

Please get on, Mister Sexton, said Jerry, feeling rather important.

Yes, get on, get on, repeated Mrs. Waggetts, for Im a-longin to hear how he takes it.

240

Can you doubt? I dont, replied Mipps. I beet my head hell take it as a man, wont you, Jerry Jerk, eh?

Ill tell you when I knows wot it is, replied the boy.

Why, what a talky old party Ive become. Time was when I never uttered a wordbut doah, I was one to do. And much and quick I did, too.

We knows that very well, thank you, Mister Sexton, said Jerry. That is, we knows it if we knows your word can be relied upon.

You may lay to that, said Mipps, and you may lay that in our future dealings together you can depend on me a-standin by you as long as you lay the straight course with me.

Ill take your word for that, responded Jerk. Now praps you will get on?

Well, said the sexton, I must begin with the Marshthe Romney Marsh. No one knows better than you that shes a queer sort of a corner, is Romney

241

Marsh. Ive seen you a-prowlin and a nosin about on her. You scented excitement, you did, on the Marsh. You smelt out a mystery, and like a lad of adventurous spirit you wanted to find out the meanin of it all. Very natural. I should have done the same when I was a lad. Well, now the whole business is this: the Marsh dont approve of people a-nosin and a-prowlin after her secrets, see? And the sextons face grew suddenly fierce: all those lines of quizzical humour vanished from around that peculiar mouth and left a face of diabolical cruelty, of cunning, and of deceit. But Jerk was not easily unnerved or put out of countenance. There was something about Mipps that put him on his mettle and stimulated him. He liked Mipps, but he liked to keep even with him, for his own self-respect, which was very great, for in some things Jerry Jerk was most inordinately proud.

Oh, the Marsh dont approve, eh? And who or what might be the power on the Marsh to tell you so?

242

The great ruler o the Marshthe man with no name who successfully runs his schemes and makes his sons prosperous.

Thatll be the squire, then, said Jerry promptly, for hes the Leveller of the Marsh Scots, aint he? He makes the laws for the Marshmen, dont he?

He does that certainly, agreed the sexton. But whether or no hes the power what brings luck to the MarshmenMarshmen, mind you, worthy of the nameneither you nor me nor nobody can tell. Sufficient for us that the Marsh is ruled by a power, a mysterious power, wot brings gold and to spare to the Marshmens pockets.

Ah, then, said Jerry, with his eyes blazing, then I was right. There are smugglers on the Marsh.

There are, said the sexton; and its wealthy men they be, though youd never guess at it, and darin, adventurous cusses they be, and rollickin good times they gets, and no danger to speak of, cos the whole blessed concern is

243

run by a master brain wot never seems to make mistakes, and it was this same master brain wot agreed that you should share the privileges o the Marsh, and I was ordered to recruit you.

Oh! and whatll be required o me? asked Jerk, supposin I thinks about it.

Youll be given a horse, and youll ride with the Marsh witches, learn their trade, and be apprehended to their callin.

And how do you know I wont blab and get you and your fellows the rope? asked Jerry bravely.

Because weve sized you up, we as, and we dont suspect you of treachery. If we did, it wouldnt much matter to us, though I should be right sorry to have been disappointed in you, for I declare I dont know when I took to a young man like I as to you. Youre my fancy, you are, Jerry. Just like I was at your age. Mad for adventure and for the life of real men.

244

Yes, but just supposin that I did disappoint you, Mister Sexton? Its well to hear all sides, you know.

Aye, its well and wise, too, and Ill tell you. If it was to your advantage to betray usto that captain prapswell, I daresay youd do it now, wouldnt you?

I dont know, said Jerk; all depends. Praps I might, though. You never knows, does you?

No, you never knows. Quite right. But youd know one thing: that go where you would, or hide where you liked, wed get you in time, and when we did get you it ud be short shrift for youyou may lay to that.

I daresay, said Jerry, unless, of course, I got you first.

Youd have a good number to get, my lad, laughed the sexton. But its no use a-harguin like this. You wont betray us when it dont serve your turn to do so, and it wont do that, cos we has very fine prospects open for you, and

245

advantages. Why, we can set you in the way of rollin in a coach before weve done with you, and who knows, years hence, when youre older than you be now, who knows but what you might not succeed to the headship. If anything was to happen to the great chief wots to prevent you from taken his place, eh? Youre smart, aint you? Theres no gainsayin that, now, is there, Missus Waggetts?