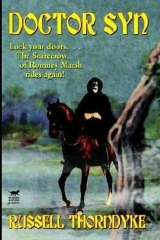

Текст книги "A Smuggler Tale of the Romney Marsh"

Автор книги: Russell Thorndike

Жанр:

Исторические приключения

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 10 (всего у книги 15 страниц)

Chapter 26

The Devils Tiring House

If the village was abed by ten oclock, the coffee shop was very much alive at half an hour after midnight. Jerk, according to his instructions, found himself tapping upon the black window at that very hour and immediately found himself hauled into the house by Mr. Mipps himself. The sexton wore a voluminous riding cloak, heavily tippeted, and a black mask hid the upper part of his face, but Jerk could see by a glance at the fine sharp jaws that Mipps had laid aside his oiliness of manner, his sarcastic wit, and cringing self-complacency, and was allowing the real man that was in him to shine forth for

276

once in a way probably for his express advantage. Jerk now saw the iron qualities in the sexton that had struck the love spark upon the flinty bosom of Mrs. Waggetts, for as Mipps walked about among his men, from room to room, and in and out of the coffin shop, which was heavily shuttered, he carried a power upon his shoulders that would have done credit to Boney himself. And the company that Jerk found himself amongwell, if the young hangman had suddenly found himself in the greenroom of Drury Lane Theatre in the midst of the great play actors, he could not have been more surprised, for there, collected altogether, were the jack-o-lanterns, the Marsh witches, and the demon riders, all preparing themselves as for a country fair. Grizzly old men, fishermen, and labourers, as the case might be, were arranging themselves in torn rags of womens garments, and with a few deft touches of Mippss hands, lo! the fishermen and labourers were no more, and Marsh witches took their place. Similarly were the big fellows, hulking great men of Kent,

277

metamorphosed into demons, enormous demons upon whose faces Mipps stuck heavy moustaches and hairy eyebrows of a most alarming nature. The grizzled ones likewise used horsehair in long streamers from their conical hats, so that their appearance as witchfolk should be the more pronounced. There were also three little boys and two little girls dressed as jack-o-lanterns. They were much younger than Jerk, but their rigouts filled him with envy.

Gentlemen, said Mipps, leading Jerry into this motley throng of eccentrics, the new recruit. A young man wot has the eye of an eagle and the nerves of a steel blade. Those who quarrels with this young gentll come off worst, if Im not mistook, but them wot be his friends can bank on his good faith, for hes as staunch as a dog. Get your brandy flasks out, my devils, and lets drink to our new recruit. Jerry Jerk his name is, but accordin to custom we drops all mention of private names in this organization; so up with your glasses whilst I rechristen him. We has power, we has, we has devils amongst

278

us of very great powers, for we has lawyers, and farmers, and squires, and parsons wot be in league with us, but the greatest enemy we has is not the revenue swabs, nor the Admiralty uniforms, nor the bloody redcoats, nor the Prince RegentGod bless him for a vagabond and a rip!no, I thinks you knows who we fears more than all that ruck?

Jack Ketch! Jack Ketch! whispered the horrible creatures.

Why, right you are, for Jack Ketch it be, retorted the sexton. And heres a man wots goin sooner or later to be a Jack Ketch. Hes got all the gifts of the hangman, he hasjust that jolly way with him, he hasand so youll all be delighted to hear as how hes joined us, for with Jack Ketch as our friend well cheat the black cap on the gallows. Gentlemen, Jack Ketch. Therefore they all drank to Jerk with much spirit, and Jerk, having been presented with a flask, pledged them in return and was introduced to all severally by the sexton. This is Beelzebub, knocked over a good round dozen revenue swabs in your time,

279

aint you, Beelzebub? And this is Belch the demon, the finest rider we ever had in our demon horse, and heres Satan, and this be Catseyes, the weirdest old witch you ever met with in a story book, Ill wager, and so on until such a vast collection of weird names had been rammed into Jerks brains that he felt quite overpowered. However, when his own particular uniform was produced for him to don, his interests were requickened, and before Mipps had half finished attiring him in the strange rags Jerk would have sworn that it wasnt himself he saw in the old cracked mirror.

And now, Jack Ketch, said Mipps, you only has to follow me into the coffin shop to get your allowance of devils face cream, then I thinks youll feel real pleased with yourself.

Into the weird coffin shop accordingly Jerry followed the sexton, and there was that black cauldron that he remembered so well. Now he would discover its use. Mipps stirred the contents and with a great brush began daubing Jerrys

280

face. The curious smell made the youngster close his eyes and he felt the brush pass over them.

Now, said the sexton, I blows out the candles and you shall see. Jerry opened his eyes as the sexton blew out the lights. Bring the mirror! called the sexton to the other room. And then into the coffin shop came the other members of the company, and the mystery of the demon riders was explained, for in the dark room each diabolical face glistened like the moon, and when the cracked mirror had been held up before him he saw that he in his turn burned with the same hellfire. Its now time, Satan, to get the scarecrow in, and you, Beelzebub, go and paint the horses with whats left in that cauldron.

Beelzebub obeyed the sexton promptly and, picking up the cauldron, went to the back of the house, Satan accompanying him on his different errand namely, that of bringing in the scarecrow, a thing that puzzled Jerry exceedingly.

281

Mipps seemed to read his thoughts, for he approached and whispered: Jack Ketch, youre a-wonderin about the scarecrow now, aint you? Well, youve noticed him, I dare say, all dressed in black, at the bottom of my turnip field, aint you?

Yes, replied the new christened Jack Ketch; Ive noticed him as long as I can remember, and a very lifelike scarecrow I considers him to be.

Youre right, replied the sexton; its the best scarecrow I ever seed, for its lifelike and no mistake, and if you keeps your eyes open youll see him a bit more lifelike to-nightyou wait.

Satan soon reappeared bearing on his shoulder the dead lump of the scarecrow. Mipps indicated an old coffin that lay on the floor behind the counter of the shop and Satan at once pushed the scarecrow into it, and covered him with a lid.

282

Hell be there till the works done, said Mipps, for you see the great man himself rides out at nights as the scarecrow, and if you keep your eyes open youll spot him. Now, Beelzebub, as that terror reappeared, I take it that them horses is all ready; so bear in mind that my friend Jack Ketch is new to the game, and stick by him, and good luck to you devils, and may the mists guard the legion from all damned swabs! And so the company filed out of the Devils Tiring House after receiving this parting blessing at the hands of the sexton.

Aint you coming along, Hellspite? said one of the ghastly crew to the sexton.

No, Pontius Pilate, I aint, replied Mipps, for me and the blunderbuss is a-goin to watch that damned meddlesome captain.

And so they left him there, Beelzebub leading Jerry by the hand out of the back door of Old Tree Cottage.

283

Chapter 27

The Scarecrows Legion

The company found their steeds in the turnip field at the back of the house, guarded so religiously during the daytime by the old scarecrow that now reposed in the coffinhorses and ponies decked out with weird trappings and all tethered to a low fence that bordered one of the dykes. Jerrys horse, or, rather, the missing schoolmasters horse, was brought to him by Beelzebub himself, whom Jerry very soon discovered to be a most entertaining and affable devil. It was fortunate indeed for Jerry that he was a good rider, and had a knowledge of the Marsh, for the cavalcade immediately set out across the

284

fields, breaking into a high gallop, leaping dykes and sluices in such a reckless fashion that it was a marvel indeed to the boy that his old scragbones could keep pace with them; for Beelzebub rode at his side on a strong farm horse and kept urging him to a higher speed. It was nothing more nor less than a haphazard cross-country steeplechase, and the young adventurer was caught in the thrill of it. How exhilarating it was to ride through the night with those reckless fellows, but he would not altogether have relished it had Beelzebub not proved himself an indefectible and capable pilot.

Heels in hard, Jack Ketch, when I tell you. Now! And hard went the heels in, and neck to neck went the horses straight at the broad dyke. Yoikes! And up they would go, crashing down again into the rush tops on the far side. And in this way they traversed the Marsh for six miles till they reached the highroad under Lympne Hill. There they drew rein at a spot where three roads met. At the bend of these roads Jerry could see a man on a tall gray horse.

285

Thats the Scarecrow, whispered Beelzebub. Thats the great man hisself.

One of the jack-o-lanterns trotted off on his pony toward this figure, and Jerk saw him salute the Scarecrow, who handed him a paper. Saluting again, the youngster came back to Beelzebub, who took the paper from him and read it carefully by the light of the young jacks lantern. These boys carried lanterns fixed upon long poles, bearing them standard fashion as they rode.

As he was reading, Beelzebub kept catching in his breath in an excited manner, and as he tucked the paper away in his belt he muttered: May the Marsh be good to the Scarecrow to-night! Jerry instinctively looked down the road to where the Scarecrow had been standing, but horse and rider had disappeared. Ah! Jack Ketch, said Beelzebub, you are wondering wots become of him, eh? Youd need an eye of quicksilver to keep sight of him. Here, there, and everywhere, and all at once he is, and astride the finest horse

286

on Romney Marsh, a horse wot ud make the Prince Regents mouth water, a

horse more valuable to the Scarecrow than the Bank of England ud be.

But wheres he gone to? asked Jerry.

About his business and thine, Jack Ketch, answered Beelzebub.

I wish Id seen him go, returned Jerry, for I likes to see a good horse on the move. He went very silent, didnt he?

Youll never hear the noise of the Scarecrows horse a-trottin, Jack Ketch, cos hes got pads on his hoofs. Ah! hes up to some tricks, is the Scarecrow, and, by hell! hell need em to-night.

Why? asked Jerk.

Because hes had word passed from Hellspite that the Kings men are out, and Scarecrow thinks as how we may have to fight em.

And dont you want to do that?

287

Why, you see it ud be awkward if any of us got wounded, as wounded men aint easy things to hide in a village now, is they? and it ud be a difficult business to explain. Though, come to that, Scarecrow aint never put out for an explanation o nothing.

As he was speaking, Beelzebub took Jerrys rein and started off again at the head of the cavalcade. Their way was now along the road the Scarecrow had gone, and when they had ridden for about half a mile they again sighted him, sitting his horse stockstill in the middle of the road, but this time he was not alone, for there were some half-dozen men leading packponies from the road into a large field. Toward this field Beelzebub led his cavalcade, and consequently they had to pass the grim figure called the Scarecrow. Jerry was ambitious to get a near view of this strange personage, for he wanted if possible to pierce his disguise and see if he could recognize the features. But the nearer he got, the stranger the strange figure became. If it was any one that he knew,

288

then it was only the scarecrow in Mippss turnip field, for he was as like that as two peas are alike to each other.

And the voice was not like any voice he could put an owner to, although there was something familiar in it. It was a hard, metallic voice, the voice of a commander.

The Kings men are watching the Mill House Farm, so, Beelzebub, you will circle the packponies as usual till we get half a mile from the house, then you will cut off and decoy them from the rear. If your attack is sudden and fierce they will have all they can do to defend themselves, and so that will afford the Mill House Farm men time to get their packponies in with the others. I will see that they get them away safely, and when you have shaken off the Kings men pick us up again on the Romney road opposite Littlestone Beach. Understood?

Understood, Scarecrow, understood, replied Beelzebub promptly.

289

And, went on the strange man, you will stick by Jack Ketch as far as possible, and dont let him get into any needless danger. I want him to see all the fun that is possible, but I dont want any hurt to come to him. If I alter the plans, Ill pass the word. Understood?

Understood, Scarecrow, understood, repeated Beelzebub.

Then off you go!

And off they did go, the packponies, trotting under their heavy loads of wool, keeping along the edges of the field, and this with a very good purpose, for where the dykes run zigzag over Romney Marsh a thick mist arises some eight feet high, and even upon nights of full moon these mists hang about the dykes like heavy rolls of a spiders web, contrasting strangely with the rest of the country, which is all bright and easily seen. And now Jerk had to ride even faster than before, for the packponies, entirely hidden by the mist curtains, were circled and circled all the way by the galloping demons and jack-o

290

lanterns, these last swinging their pole lights round their heads and uttering strange cries like those of the Marsh fowl, weird and ominous. This accounted, then, for all the ghost tales he had heard, for all the ghostly things those not in the secret had seen upon the Marsh, and a very clever scheme Jack thought it was, and a very good way of clearing the ground of the curious. For there is no power like superstition, and nothing that spreads quicker or is more grossly exaggerated than tales of horror and fear. So on they rode in wild circles round and round the packponies. Beelzebub was the actual leader. He it was who gave the orders, but the mysterious Scarecrow would dash out of the mist every now and again just to see that all was well with the legion, and then as quickly would he disappear, borne away like a ghost upon that spectral gray thoroughbred. and round the packponies. Beelzebub was the actual leader. He it was who gave the orders, but the mysterious Scarecrow would dash out of the mist every now and again just to see that all was well with the legion, and then as quickly would he disappear, borne away like a ghost upon that spectral gray thoroughbred.

Jerry of course knew the terror with which the pallid host could affect the unwary wayfarerfor had he not seen them himself on the night of

291

Sennacheribs murder?but had he needed other proof he would have got it in the case of a small encampment of gypsies. They were not a recognized band of gypsies, but a wandering family, tramping from town to town, from village to village, getting what they could here and what they shouldnt there, to keep the poor life in their bodies. The gallopers came upon them in a ditch. They had lanterns there and a small fire around which three men and a young lad were sleeping. There was an old crone rocking herself to sleep on one side of the fire, and opposite, between two of the sleeping men, was a younger woman. Her garments were tattered and ragged to the last degree, and her shoulders and arms showed bare, for she had wrapped her shawl round the babe that was crying in her arms. The sudden appearance of the awful riders spread instant panic in this little circle. The old crone shrieked to her menfolk to awake, but before they could get to their feet the horses were upon them. Beelzebub, with daredevil precision, rode straight through the wood fire, his horse bellowing

292

with fright as he scattered the crackling sticks. The young mother just avoided Jerrys horse as he came crashing through after Beelzebub, and the shriek of fear that she gave made Jerry turn heartsick as he reined in his mount.

An ill-famed baggage, Ill be sworn, said Beelzebub. Twould have been a good thing had you ridden her down, and as for the brat, such devil spawn should be put out of their misery.

Now I should have thought devil spawn would have had rather a way with us. At which sally Beelzebub clapped Jerk on the back, and declared that he was a good Ketch, a remarkable good Ketch, and as the young recruit had all he could do saving his own neck every minute as they leaped backward and forward over the dyke, this unpleasant episode was forgotten, or, rather, slid back into his brain like the memory of a nightmare slides when we dream again. On they dashed, but stopping at numerous farms on the way, where they always found more packponies waiting to join the cavalcade. And the

293

Scarecrow was always somewhere. As soon as any little hitch occurredas one frequently did when the men placed the temporary bridge over the dykes for the transit of the packponiesthe Scarecrow would suddenly appear in their midst, giving sharp orders, whose prompt obedience meant an instant end to the difficulty, whatever it chanced to be. But it was the laying of this same temporary bridge that caused most of the delays, for it was a cumbersome thing to move about, and it had to be built strong enough to support the weight of the packponies. These ponies, too, caused considerable bother at some periods of the march, as their packs of wool would sometimes shake loose from the harness, and the cavalcade would have to stop while this was being remedied. But although the packponies stopped often, the demon riders were never allowed that luxury. Beelzebub untiringly flagged the horse round and round, now in large circuits, now in small circles, always ringing in the packponies from any prying eyes. It would have meant death to any one who got a view

294

within that sweeping scythe of cavalry. And as murders on the Marsh were all put down to the Marsh devils, except in the case of Sennacherib Pepperfor there was then a likely assassin known to be at large upon the Marsh to lay the deed toand because of the dreaded superstition that had grown in the minds of Kentish folk, the smugglers were utterly callous as to what crimes they perpetrated, for they were as safe from the law as the most law-abiding citizen, for those who didnt credit the existence of murdering hobgoblins at least possessed sufficient fear of the smugglers themselves to leave them alone; for, after all, it was not business of any one but the revenue men, and so to the revenue men were they left, and in nearly every record it may be seen that the revenue men got the worst of it.

295

Chapter 28

The Fight at Mill House Farm

Mill House Farm was the last on Beelzebubs list, and in the dyke facing the house, but on the other side of the highroad crouched the Kings men, commanded by the captains bosun. They were as still as mice, but the captain had given strict orders to the bosun on that score, but they need not have put themselves to such pains, for owing to the extreme vigilance of Sexton Mipps the smugglers knew exactly where they were and what they were going to do.

296

Now it is depressing to the most seasoned fighters to have to crouch for hours in a soaking muddy dyke waiting for an outnumbering enemy; for it was common knowledge that if smuggling was carried on upon the Marsh, it was well manipulated and relied for its secrecy upon the strength and numbers of its assistants. So the bosun had no easy task in keeping his men from grumbling; for whatever Captain Collyers opinion may have been with regard to maintaining the law according to his duty, it was pretty evident that his men had no great relish for the task, and the bosun heartily wished that the captain had not left him responsible, for his absence was having a poor effect upon the men, and the unfortunate bosun was greatly afraid that they would fail to put up a good fight when the time came. It is one thing to fight an enemy, but quite another to shoot down your own countrymen, and although every man jack of them was itching for the French war, they felt no enthusiasm for this suppression of smuggling, for the whole of the countryside would have taken

297

the side of the lawbreakers, and who knows how many of these same Kings men had not themselves done a very profitable trade with the illegal cargoes from France.

These were the feelings that existed as the Kings men lay in the dyke opposite Mill House Farm, listening to the noise of ponies hoofs in the yard, and waiting to fire upon any one who presented himself.

But the order Not to kill, but to fire low, also damped their spirits, for what chance would they have against desperate fellows keeping their necks out of the rope, who would not hesitate but would rather aim to kill?

The bosun had great difficulty in preventing one old seadog who lay next him in the ditch from voicing his opinion of the proceedings in a loud bass voice, but what he did say he after all had the good grace to whisper, though a whisper that was none too soft at that.

298

What the hells the sense, Mr. Bosun, of sending good seamen like we be to die like dogs in this blamed ditch? Aint England got no use for seamen nowadays? Taint the members of Parleyment wotll serve her when it comes to fighting, though they does talk so very pleasant.

They dont talk as much as you do, was the hushed retort of the bosun.

Look ye ere, Job Mallet, went on the seadog, youve been shipmate o mine for longer than I well remembers, and you be in command here. Well, I aint a-kickin against your authority, mind you, but Im older than you be, and I want to voice my opinion to you, which is also the opinion of every mothers son in this damned ditch. Why dont we clear out of this and be done with the folly? We looks to you, Job Mallet, I say we looks to you as our bosun, and a very good bosun you be, we looks to you, we does, to save us bein made fools of. We wants to fight the Frenchies and not our own fellows. The Parleyments a-makin a great mistake puttin down the smugglers. If they only talked nice to

299

em theyd find a regiment or two o smugglers very handy to fight them ugly Frenchies. For my own part I dont see why the Parleyment dont put down other professions for a bit and leave the smugglers alone. Why not give lawyers a turn, eh? They could do with a bit o hexposin! Dirty swabs! And so could the doctors wot sell coloured water for doses. Bah! dirty, dishonest fellows! But, oh, no! Its always the poor smugglers who be really hard-working fellows; and very good fighters they be, too, as well soon be called upon to see.

At this time Job Mallet tried to silence him, but threats, persuasions, and arguments were all alike useless.

Old Collywobbles thinks the same as wot we does.

Ill have you to remember, whispered the bosun stiffly, that I bein in command in this ere ditch dont know as to who you be alludin when you say Collywobbles. I dont know no one of that name.

300

Oh, aint you a stickler to duty? chuckled the seadog. Still I respecs you fer it, though praps youll permit me to remind you as how it was you in the focsle of the Resistance as gave the respected Captain Howard Collyer, R.N., the pleasant pet name of Collywobbles. Though praps thats slipped your memory for he moment.

It has, answered the bosun.

Very well, then, but you can take it from me as how it was, so there, and a very clever name it be, too; but there, you always was one of the clever ones, Job Mallet.

I wish I were clever enough to make your fat mouth shut, I do, muttered the bosun.

Now, then, Job Mallet, dont you begin getting to personalities. But there, now, I dont want to quarrel with you. Youve always had my greatest respecs, you has, and as well probably be stiff uns in a few minutes, we wont quarrel,

301

old pal. But I give you my word that I dont like being shot down like a rabbit, and Im sorry as how its you as is in command, cos if it was any one else I declares Id get up now and walk home to bed.

If Captain Collyer was here, you know youd do nothing of the sort.

Why, aint he here? Thats wot I wants to know. Strike me dead! its easy enough to send out poor old seadogs to be shot like bunny rabbits. I could do that. There aint no pluck in that, as far as I can see, though praps I be wrong, and if I be wrong, well, Ill own up to it, for I dont care bein put in the wrong of it when I is in the wrong of it.

You aint a-settin a very good example to the young men, Im thinkin, said Job Mallet. You, the oldest seaman here, and a-grumblin and a-gossipin like an old housewife. You ought to think shame on yourself, old friend.

Oh, well, growled the other, I wont utter another blarsted word, I wont. But if you does want to know my opinion in these ere proceedins, itshell!

302

I dont say as how I dont agree with you, returned Job Mallet, but there it is and weve got to make the best of it. It wont do no good a-grumblin. Well make the best of a bad job, and I hopes as I for one will be able to do my duty, cos I dont relish it no more than you do.

Well, strike me blind, dumb, and deaf! thundered the seadog in a voice of emotion as he clapped Job Mallet on the back, if Ive been a snivellin powder monkey I ought to be downright ashamed of myself, and seein as how I be the oldest seaman here, insteadwell, Im more than damned downright ashamed, Job Mallet, thank you! You set a good example to us all, Mister Bosun, and Ill stand by you for one. Damn the smugglers, and wait till I get at em, thats all!

Thank yer, said the bosun, but youll greatly oblige me by keeping quiet, cos here be the smugglers, if I aint mistook.

303

Indeed at that instant along the road came the sound of the sharp, quick steps of the packponies. At present they were hidden in the mist which floated thickly about that part of the Marsh, but they could not only hear the ponies but a sound of a voice singing as well. This voice was raised in a wailing monotone and the words were repeated over and over again. They were intended for the ears of the wretched sailors who were waiting in the ditch for the attack:

Listen, oh, you good Kings men who are waiting to shoot us from the damp ditch. We have got your kind captain here, a blunderbuss alooking at the back of his head. If you fire on us, good Kings men, then the blunderbuss will fire at the good captain, and then:

All the Kings horses and all the Kings men Could not put captain together again.

304

Even if the words were not sufficient to explain the situation to the sailors, the first figures of the cavalcade were all sufficient. A donkey led by two jacko– lanterns on foot jolted out of the fog. Upon its back was a man bound and gagged, supported on either side by two devil-men. That the gagged wretch was the captain needed no words to tell, for his uniform showed by the lanterns light, and there right behind him, sure enough, was the blunderbuss in question, pointed by a snuffy little devil called by his colleagues Hellspite, who sat hunched up on a shoddy little pony. This little group halted at a convenient distance from the sailors in the ditch, and Hellspite again rehearsed his little speech, ending up with:

All the Kings horses and all the Kings men Could not put captain together again.

305

Now the poor bosun in command had all his life grown so used to taking other peoples orders that he didnt know what to do for the best. He liked the captain and didnt want to see him killed, though he knew what he must be suffering in his ridiculous position. He knew that had the captain but got the use of his speech he would have shouted, Fire! and be damned to em! But then the captain had not got the use of speech. The Scarecrow and Hellspite knew enough of the man to see to that, and as they had no great desire to be fired at, they had seen that the gags were efficient. So it was, after all, small wonder that the old grumbling seadog next to him, who possessed a rollicking vein of humour, laughed until he rolled back into the mud, for the sight was enough to make the proverbial cat laugh, much less a humorous old tar, and the rest of the men were divided into two classes, some following the example of the bosun and being struck stiff with amazement and powerless wrath, others joining the laughing tar in the muddy ditch and guffawing over the ridiculous

306

situation of their captain, for he was not the build of man to sit an ass with any dignity, not being at all akin to a Levantine Jew, but very absurd in his naval uniform, with the cocked hat literally cocked right down over his nose. It was this sudden surprise that made the sailors utterly unprepared for what followed. A large party of horse swept out of the mist behind them, and when they turned to see what fresh thing was amiss there was a gallant line of terrible cavalry pulling up on their haunches a few yards in their rear. Thus they were cut off on both sides: at their back the devils with flaming faces, on horses of alarming proportions, and in front, their captain, waiting for them to shoot, to meet his own death by the little demons blunderbuss:

If you fire, you good Kings men, Then the devil shall blarst your captain.

307

And you as well, you good Kings men! shrieked and howled the terrible demons at the back, who covered with pistols or blunderbuss every Jack Tar in the ditch.

Then another rider appeared on the scene. He was tall, thin, and of ungainly appearance, and he rode a light gray thoroughbred. He was the Scarecrow, and all the devils hailed him by that name as he appeared. Behind him came the packponies, some sixty or seventy in all, and on each pony was a wool pack that would have meant a human neck to the Kings hangman if only Collyer were free to work his will. The Scarecrow drew up in the road and watched the great procession of ponies pass along toward the coast. When they had all but passed he gave a signal, and the doors of Mill House barn were opened and ten more heavily laden ponies trotted out and joined the snake of illegal commerce that was wriggling away to the sea. Then like some field-marshal upon the field of battle did the Scarecrow slowly ride over a small bridge and then along the