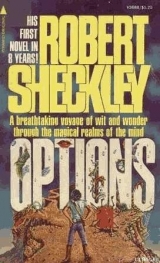

Текст книги "Options"

Автор книги: Robert Sheckley

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 10 страниц)

11

"What I'm going to do," said the Countess of Melba, "I am going to take the pledge."

"Then for the love of God Almighty," cried the Duke of Melba, "get on with it, doget on with it, and stop nattering on about it."

"I do not believe in you any more," the Duchess of Melba said.

At that instant the Duke of Melba vanished like the insubstantial thing he was and, as far as I'm concerned, always will be.

Mishkin remembered something that had happened to him as a little boy on a stud ranch near Abilene. But he didn't pursue it because he couldn't see how it would help him in his present circumstances, whatever they were.

"One can be on the verge of violent death," said the robot, "and still be bored. I wonder why that is so?"

"One can get damned sick of the thoughts of robots," Mishkin replied.

The forest died. It was an attack of the floral version of hoof and mouth disease that had wracked such ruin around the countryside. Nothing for it, we will simply have to get along without that forest.

12

Mishkin was walking through a large parking lot. It was a beige parking lot with green and yellow stripes. The parking meters were mauve, and the crumpled old newspapers were scarlet and bronze. It was a humdinger of a parking lot.

"This seems to be a parking lot," Mishkin remarked.

"It does seem so, doesn't it?" the Duke of Melba replied, twirling the ends of his long blond moustaches. "Reminds me of a story. Rather good story. Friend of mine was staying at a friend's house in Surrey. Cotswolds, actually. He had retired for the night in a room that was purported to be haunted. My friend thought that a rather piquant touch, but he didn't buy it, of course. No one does. Well, then. My friend set the guttering candle down by his bedside – the place had no electricity, you see; or rather, it didhave electricity but a sudden storm had sent it all kaput. He was just settling in for the night, in quite a calm mood, when…"

"Excuse me," Mishkin said. "Who are you?"

"Duke of Melba," said the Duke of Melba. "But call me Clarence. I don't hold with all of that title nonsense. I don't believe I caught your name."

"That's because I didn't throw it," Mishkin said.

"Oh, I say, that's rather good. Original?"

"It was, once," Mishkin said.

"Very good!"

"My name is Mishkin," Mishkin said. "I don't suppose you happened to see a robot anywhere around here?"

"I didn't actually."

"Strange. He just vanished."

"Nothing strange about that," the Duke of Melba said. "Just a minute ago my wife remarked that she didn't believe in me, and lo and behold, I just vanished. Strange, isn't it?"

"Very strange," Mishkin said. "But I suppose it does happen."

"I suppose it does," Clarence said. "After all, it just happened to me. Damned funny feeling, vanishing."

"What does it feel like?"

"Hard to put your finger on it. A sort of insubstantialthing, if you know what I mean."

You're sure you didn't see my robot?"

"Reasonably sure. I suppose you were fond of him?"

"We've been through a lot together."

"Old war buddies," the Duke said, nodding and untwisting his moustaches. "Nothing quite like old war buddies. Or old wars. I remember a time outside of Ypres…"

"Excuse me," Mishkin said. "I don't know where you came from, but I think that I must warn you that you have vanished or been vanished into a place of considerable danger."

"It's uncommonly kind of you to warn me," the Duke said. "But, actually, I'm in no danger at all. The danger number is your movie, whereas I am in an entirely different and much less satisfactory sequence. Projection doth make mockery of us all, as the poet said. Whimsical anachronism is more my line of country, old chap. Now, as I was saying…"

The Duke of Melba interrupted himself by stopping. A shadow of discontent had just crossed his mind. He was unsatisfied with his delineation of himself. All that he had presented so far was the fact that he had long blond moustaches, sounded vaguely English, and seemed a little silly. This seemed to him insufficient. He decided to rectify the situation at once.

The Duke of Melba was a large and impressive individual. His eyes were a frosty blue.

He bore a resemblance to Ronald Colman, though the Duke was handsomer, more bitter, and possessed more cool. His hands were finely shaped with long tapering fingers.

Noticeable also were the little crow's-feet at the corners of his eyes. These, together with the feathering of grey at his temples, did nothing to detract from his attractiveness; quite the contrary, they gave him a bold, brooding, weather-beaten appearance that the opposite sex (as well as many members of his own sex, not all of them gay) found distinctively attractive. Taken all in all, he was the man you would pick to advertise your oldest scotch, your best line of clothing, your most expensive motorcars.

The Duke thought that over and found it good. A few things were missing. So he gave himself the faintest suggestion of a limp, just for the hell of it and because he had always considered a limp to be mysterious and attractive.

When he was through, the Duke of Melba was fair pleased. The only thing that galled him was the fact that his wife had caused him to vanish. That seemed to him a very castrating thing to do.

"Do you know?" he said to Mishkin, "I have a wife. The Duchess of Melba, you know."

"Oh. That's nice," Mishkin said.

"In a way it is, I suppose. But the thing is, I don't believe in her."

The Duke smiled to himself: an attractive smile. Then he frowned: an attractive frown, for his wife appeared suddenly in front of him.

The Duchess of Melba took one good look at the Duke, then swiftly changed her appearance. Her hair went from grey to chestnut brown with red highlights. She became tall, slender, with medium-large boobies and a delicious ass. She gave herself delicate bones in her wrists, a faint, blue vein that throbbed in her forehead, a beauty mark shaped like a star on her left cheek, fantastic legs, a Pierre Cardin outfit, a Hermes handbag, shoes by Riboflavin, a tantalizing smile smiled by long, slim lips that didn't need any lipstick because they were naturally red (it ran in the family), a solid gold Dunhill lighter, emaciated cheeks, raven black hair with blue highlights, and a big sapphire ring instead of a gold-plated wedding band.

The Duke and the Duchess looked at each other and found each other admirable. They strolled away arm and arm into the nowhere they had made each other vanish into.

"All the best," Mishkin called after them. He looked around the parking lot but he couldn't find his car. It was one of those days.

At last a parking lot attendant came ambling up to him – a short fat man in a green jumper with the words AMRITSAR HIGH SCHOOL ALL-STARS embroidered over his left breast pocket. The attendant said, "Your ticket, sir? No tickee, no caree."

"Here it be," said Mishkin, and from the transverse pocket of his slung pouch he removed a piece of red pasteboard.

"Don't let him take that ticket!"a voice called out.

"Who is that?" Mishkin asked.

"I am your SPER robot presently disguised as a 1968 Rover TC 2000. You are under the influence of a hallucinating drug. Do not give the attendant that ticket!"

"Give ticket," said the attendant.

"Not so fast," said Mishkin.

"Yes, fast," said the attendant, and reached out.

It seemed to Mishkin that the attendant's fingers split into a mouth. Mishkin stepped back. Very slowly the attendant came towards him. Now he could be seen as a kind of large snake with wings and a forked tail. Mishkin avoided him without trouble.

Mishkin was back in the forest (That damned forest!) The robot was standing beside him. A large, winged snake was advancing very slowly on Mishkin.

13

The snake had a mouth that secreted fantasies. His very breath was illusion. His eyes were hypnotic, and the movement of his wings cast spells. Even his size and shape were matters of illusion, for he was capable of changing himself from gigantic to infinitesimal.

But when the snake had made himself tinier than a fly, Mishkin deftly captured him and shut him up in an aspirin bottle.

"What will you do with him?" the robot asked.

"I will keep him," said Mishkin, "until it is the proper time for me to live in fantasies."

"Why is that time not now?" the robot asked.

"Because I am young now," Mishkin replied, "and it is time for me to be living adventures and to be making actions and suffering reactions. Later, much later, when my fires have dimmed and my memories have lost their bright edge, then I shall release this creature. The winged snake and I will walk together into that final illusion that is death.

But that time is not now."

"Well spoken," the robot said. But he wondered who was speaking with Mishkin's mouth.

So they kept going across the forest. The aspirin bottle was sometimes very heavy, sometimes light. It was evident that the creature had power. But it was not enough to dissuade Mishkin from the work that lay ahead of him. He didn't know what this work was, but he knew that it didn't lie in an aspirin bottle.

14

Mishkin and the robot came to a ravine. There was a plank across the two sides of the ravine. Looking down, one could see a tiny thread of water thousands of feet below.

This was noteworthy, for the ravine had a natural grandeur and attractiveness. But more striking by far was the plank across the two sides of the ravine. There was a table on the plank, near the middle. There were four chairs at the table, and four men sat in the chairs. They were playing a game of cards. They had full ashtrays beside them. There was an unshielded light, suspended by nothing visible, burning palely above their heads.

Mishkin approached and listened to them for a while.

"Open for a dollar."

"Fold."

"Call."

"Raise."

"And another dollar."

They played with concentration but with evident fatigue Their faces were stubbly and pale, and their rolled-up sleeves were grimy. They were drinking beer from no-neck bottles and eating thick sandwiches.

Mishkin walked up and said, "Excuse me."

The men looked up. One of them said, "What's up, bub?"

"I'd like to get by," Mishkin said.

They stared at him as if he were crazy. "So walk around," one of the men said.

"I can't," Mishkin said.

"Why not? You lame or something?"

"Not at all," Mishkin said. "But the fact is, if I tried to walk around I would fall into the ravine. You see, there's no room between the chairs and the edge; or rather, there's an inch or two, but my balance isn't good enough for me to risk it."

The men stared at him. "Phil, did you ever hear anything like that?"

Phil shook his head. "I've heard some weird ones, Jack, but this takes the fur-lined pisspot for sure. Eddie, what do you think?"

"He's gotta be drunk. Huh, George?"

"Hard to say. What do you think, Burt?"

"I was just going to ask Jack what he thought," Burt looked at Mishkin. In a not unkindly manner, he said, "Look, fella, me and the boys are having this private poker game here in room 2212 of the Sheraton-Hilton, and you come in and say that you'll fall over the edge of a ravineif you walk around us, when the fact of the matter is that you shouldn't be in our room in the first place, but being here, you could walk around us all day without anything happening to you since this happens to be a hotel not a ravine."

"I think you are labouring under a delusion," Mishkin said. "It happens that you are not in a hotel room in the Sheraton-Hilton."

George, or possibly Phil, said, "Then where are we?"

"You are seated at a table situated on a plank over a ravine on a planet called Harmonia."

"You," said Phil, or possibly George, "are out of your ever-loving mind. Maybe we had a few drinks, but we do know what hotel we signed into."

"I don't know how it happened," Mishkin said, "but you are not where you think you are."

"We're on a plank over a ravine, huh?" Phil said.

"Exactly."

"So how come we think we're in room 2212 of the Sheraton-Hilton?"

"I don't know," Mishkin said. "Something very strange seems to have happened."

"Sure, it has," Burt said. "It's happened to your head. You're crazy."

"If anyone is crazy," Mishkin said, "you people are crazy."

The poker players laughed. George said, "Sanity is a matter of consensus. We say it's a hotel room and we outvote you four to one. That makes you crazy."

Phil said, "This damned city is full of nuts. Now they come up to your hotel room and tell you it's balanced on a plank over a ravine."

"Will you let me get by?" Mishkin asked.

"Suppose I do; where will you go?"

"To the other side of the ravine."

"If you go around us," Phil said, "you'll only come to the other side of the room."

"I don't think so," Mishkin said. "And, although I wish to be tolerant of your opinions, in this case I can see that they are based upon a false assumption. Let me get by and you can see for yourself."

Phil yawned and stood up. "I was going to the crapper, anyhow, so you can get by me. But when you reach the end of the room, will you turn around again like a good boy and get the hell out of here?"

"If it's a room, I promise to leave at once."

Phil stood up, took two steps back from the table, and fell into the ravine. His scream echoed and re-echoed as he fell into the depths.

George said, "Those goddamned police sirens are getting on my nerves."

Mishkin edged past the table, holding on to its edge, and made it to the other side of the ravine. The robot followed. Once they were both safe, Mishkin called out, "Did you see? It was a ravine."

George said, "While he's at it, I hope Phil gets Tom out of the crapper. He's been there about half an hour."

"Hey," Burt said, "where did the nut go?"

The card players looked around. "He's gone," George said. "Maybe he went into a closet."

"Nope," Burt said, "I've been watching the closet."

"Did he jump out a window?"

"You can't open the windows."

"Too much," George said. "That's really one for the books… Hey, Phil, hurry up!"

"You can never get him out of the crapper," Burt said. "How about a little gin rummy?"

"You're on," Burt said, and shuffled the cards.

Mishkin watched them for a few minutes then continued into the forest.

15

Mishkin asked the robot, "What was that all about?"

"I am reviewing the information now," the robot said. He was silent for a few minutes.

Then he said, "They did it with mirrors."

"That seems unlikely."

"All hypotheses concerning the present sequence of events are unlikely," the robot said. "Would you prefer me to say that we and the card players met at a discontinuity point in the space-time continuum in which two planes of reality intersected?"

"I think I would prefer that," Mishkin said.

"Simpleminded sod. Shall we go on?"

"Let's. I just hope the car works."

"It had better work," the robot said. "I spent three hours rewiring the generator."

Their car – a white Citroen with mushroom-shaped tyres and a hydraulic tail-light system – was parked just ahead of them in a little clearing. Mishkin got in and started up.

The robot stretched out on the back seat.

"What are you doing?" Mishkin asked.

"I thought I'd take a little nap."

"Robots never sleep."

"Sorry. I meant that I was going to take a little pseudo-nap."

"That's OK," Mishkin said, putting the car into gear and taking off.

16

Mishkin drove across a green and pleasant meadow for several hours. He came at last into a narrow dirt road that led between giant willow trees and then into a driveway. In front of him was a castle. He awakened the robot from his pseudo-snooze.

"Interesting," said the robot. "Did you notice the sign?"

In front of the castle, tacked up on a young spruce tree, was a sign reading: IMAGINARY CASTLE.

"What does it mean?" Mishkin asked.

"It means that some people have the decency to state a simple truth, and thus to avoid confusing passersby. An imaginary castle is one that has no counterpart in objective reality."

"Let's go in and take a look at it," Mishkin said.

"But I have just explained to you. The castle is not real. There is literally nothing to see."

"I want to see it, anyhow," Mishkin said.

"You have already read the sign."

"But maybe that's a lie or a joke."

"If you can't believe what is written plain as day," the robot said, "then how can you believe anything? You have observed, I hope, that the sign is exceptionally well made, and that the lettering is plain, forthright, and not at all flamboyant. In the right-hand corner is the seal of the Department of Public Works, an unimpeachable and businesslike organization whose motto is Noli me tangere.It is evident that they have classified this castle as a public service so that no one will walk into it thinking that he is in a real castle. Or isn't the Department of Public Works a reliable service to you?"

"It is a very acceptable reference," Mishkin said. "But maybe the seal is a forgery."

"That is typically paranoid thinking," the robot said. "First, despite its solid and commonplace air of reality, you consider the sign a lie or a joke (the two are essentially the same thing). Then, when you learn the source of this so-called «joke», you think that perhaps it is a forgery. Suppose I succeed in proving to you the authenticity and sincerity of the sign makers? I suppose that you would insist, despite the accepted principle of Ockham's razor, that the sign makers are imaginary, or deluded, and that the castle is real."

"It is simply a rather unusual thing," Mishkin said, "to come across a castle and to be told that it is imaginary."

"I see nothing unusual about it," the robot said. "Since the latest revision of the truth-in-advertising statutes, ten gods, four major religions, and eighteen hundred and twelve cults to date have been labelled imaginary in accordance with the law."

17

Guided by the sacristan – a short cheerful old man with a white beard and a wooden leg – Mishkin and the robot toured the Imaginary Castle. They went down long stuffy passageways and through short draughty cross passageways, past factory-tarnished suits of armour and pre-faded, pre-shrunk tapestries depicting virgins and unicorns in ambiguous poses. They inspected the punishment cells where make-believe prisoners pretended to suffer from the vile incursions of fraudulent racks, ersatz pincers, and fake thumbscrews wielded by stoop-shouldered torturers whose commonplace horn-rimmed glasses robbed them of any pretence to credibility. (Only the pasteurized blood was real, and not even that was convincing.) They passed the armoury where snub-nosed demoiselles typed triplicate requests for the latest model Holy Grail swords and Big Barbarian spears.

They went to the battlements and saw the vats of Smith & Wesson polyunsaturated oil suitable for low-temperature anointing or high-temperature boiling. They looked into the chapel, where a boyish, red-haired priest made jokes in Sanskrit to a congregation of Peruvian tin miners, while Judas, crucified by a contrived clerical error, looked down, bewildered, from a Symbolist cross of rare woods that had been especially selected for the spiritual sensibility of their textures.

Finally, they came to the great banquet hall, within which was a table loaded with Broasted chickens, mugs of Orange Julius, chili dogs, clams on the half shell, and two-inch slices of roast beef done crisp on the outside and rare on the inside. And there were platters of soft ice cream, and trays of pizza, both Neapolitan and Sicilian, all of them with extra cheese and sausage, anchovies, mushrooms, and capers. There were foil-wrapped heroes and poorboys, and combination, multiple-decker sandwiches of pastrami, tongue, corned beef, chopped liver, lox, cream cheese, onions, coleslaw, potato salad, and dill and half-sour pickles. And there were great tureens of kreplach soup, and chicken soup with noodles. And there were cauldrons filled with lobster Cantonese, and platters piled high with sweet and sour spareribs, and waxed-paper containers of pressed duck with walnuts. And there were roast stuffed turkeys with cranberry sauce, cheeseburgers, shrimps in black bean sauce, and much more besides.

"What happens to me if I eat some of this?" Mishkin asked.

"Nothing," the sacristan said. "Imaginary food cannot nourish you; but it also cannot make you sick."

"Does it have a mental effect?" Mishkin asked, sampling a chili dog.

"It must have a mental effect," the sacristan pointed out, "since imaginary food is, literally, food for the mind. The precise effect varies with the intelligence and sophistication of the partaker. Among the ignorant and gullible, for example, imaginary food tends to be quite nourishing. Pseudo-nourishing, of course, but the nervous system cannot differentiate between real and imaginary events. Some idiots have managed to live for years and years on this insubstantial stuff, thus demonstrating once again the effects of belief upon the human body."

"It tastes good," Mishkin said, gnawing on a turkey drumstick and helping himself to a portion of cranberry sauce.

"Of course," the sacristan said. "Imaginary food always has the best taste."

Mishkin ate and ate, and enjoyed himself hugely. Then, heavy-laden, he went over to a couch and lay down. The gentle insubstantiality of the couch lulled him to sleep.

The sacristan turned to the robot and said, "Now the shit is really going to hit the fan."

"Why?" the robot asked.

"Because, having partaken of imaginary nourishment, that young man is about to have imaginary dreams."

"Is that bad?" the robot asked.

"It tends to get confusing."

"Perhaps I should wake him up," the robot said.

"Of course you should; but first, why don't we turn on the tube and tune in on his dream?"

"Can we do that?"

"You'd better believe it," the sacristan said. He crossed the room and turned on the television set.

"That wasn't there before," the robot said.

"One nice thing about an imaginary castle," the sacristan pointed out, "is that you can have pretty much what you want when and where you want it, with no necessity for tedious explanations that are always something of a bringdown."

"Why don't you focus that screen?"

"It is in focus," the sacristan said. "Here come the titles."

On the screen the following credits appeared:

Robert Sheckley Enterprises Presents

MISHKIN'S IMAGINARY DREAM

A Neo-Menippean Rodomontade

Produced in Can Pep des Correu Studios, Ibiza

"What was that all about?" the robot asked.

"Just the usual crap," said the sacristan. "Here comes the dream."