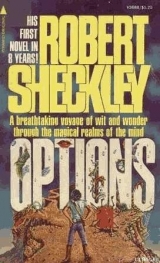

Текст книги "Options"

Автор книги: Robert Sheckley

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 2 (всего у книги 10 страниц)

6

"Tom, are you all right?"

Mishkin blinked. "I'm fine."

"You don't look fine."

Mishkin giggled: that was a very funny remark.

"What's so funny?"

"You're funny. I can't even see you, and that's funny."

"Drink this."

"What is it?"

"Nothing. Just drink it."

"Drink nothing and you turn into nothing!" Mishkin roared. With a supreme effort he opened his eyes. He couldn't see anything. He forced himself to see things. Now what?

What was the rule? Yes! Reality is achieved by the indefinite enumeration of objects.

Therefore: bed table, fluorescent light, incandescent light, stove, chest, bookcase, typewriter, window, tiles, glass, bottle of milk, coffee mug, guitar, ice bucket, friend, garbage bag… et cetera.

"I have achieved reality," Mishkin said, with quiet pride. "I'm going to be all right now."

"What is reality?"

"One of the many possible illusions."

Mishkin burst into tears. He had wanted an exclusive reality. This was terrible, this was worse than before. Now anything…

" This can't be happening," he thought. But there was the pachynert, like a dubious proof of its own reality, coming at him in an extremely plausible whirlwind of claws and teeth. Mishkin accepted the gambit. He threw himself to one side and the beast swept past him.

"Shoot!" Mishkin screamed, getting into the spirit of the thing.

"I am not supposed to kill herbivorous animals," the robot said. But there was little conviction in his voice.

The pachynert had wheeled around and was coming again, drooling. Mishkin jumped to the right, then to the left. The pachynert followed like his shadow. The massive jaws opened. Mishkin closed his eyes.

He felt a burst of heat on his face. He heard a snarl, a grunt, and the sound of something heavy falling.

He opened his eyes. The robot had finally brought himself to fire and had dropped the beast neatly at Mishkin's feet.

"Herbivorous," Mishkin said, bitterly.

"There is such a thing as behavioural mimicry, you know. In actual cases the imitative behaviour is carried to the point of living like the model predator, even to the point of eating flesh; which, to a herbivore, is both repugnant and indigestible."

"Do you believe any of that?"

"No," the robot said, miserably. "But I don't understand how that creature could have been left out of my memory files. This planet was under continual survey for ten years before a cache was established here. Nothing the size of that beast could have escaped the probes. It is no exaggeration to say that, dangerwise, Darbis IV is as well known as Earth itself."

"Wait a minute," Mishkin said. "What planet did you say this was?"

"Darbis IV, the planet for which I was programmed."

"This is not Darbis IV," Mishkin said. He felt sick, dull, doomed. "This planet is called Harmonia. They sent you to the wrong planet."

7

Tired of the flow? Sick of unity?

Then avail yourself of DIAL-AN-INTERRUPTION SERVICE!

Choose from our full line of Pauses, Beats, Breaks, Blackouts.

The robot chuckled – an insincere sound. "I'm afraid you're in a bit of a funk.

Temporary aphasic hysteria is my diagnosis, though God knows, I'm no doctor. The strain, I suppose…"

Mishkin shook his head. "Figure it out for yourself. You've been wrong several times about the dangers here. Grossly wrong. Impossibly wrong."

"It isodd," the robot said. "I can't think of a ready explanation."

"I can. They've been screwing up the shipments ever since they established this cache.

They simply screwed up on you. You were supposed to go to Darbis IV. But they sent you to Harmonia."

"I'm thinking," said the robot.

"Do that," Mishkin said.

"I have thought," the robot said. "We SPER robots are noted for the speed of our synaptic responses."

"Bully for you," Mishkin said. "What conclusion have you reached?"

"I think that, weighing all the available evidence, your hypothesis is the most apparently probable. I do indeed seem to have been dispatched to the wrong planet. And that, of course, presents us with a definite problem."

"And that means we have to do some hard thinking."

"Most assuredly. But let me point out that a creature of unknown disposition and appetites is presently approaching us."

Mishkin nodded absently. Events were moving along too fast, and he needed a plan.

To save his life he had to think, even if it cost him his life.

The robot was programmed for Darbis IV. Mishkin was programmed for Earth. And here they both were on Harmonia like two blind men in a boiler room. The most reasonable course of action for Mishkin was to go back to the cache. There he could relay the information to Earth and wait until either a replacement part or a replacement robot, or both, were shipped to Harmonia. That, however, could take months, or even years.

And the part he wanted was only a few miles away.

Still, turning back was the safest course of action.

But then Mishkin thought of the conquistadors in the New World, cutting their way through endless jungle, meeting the unknown and subduing it. Was he so much less a man than they? Had the unknown changed in any fundamental way since the Phoenicians took their ships beyond the Pillars of Hercules?

He would never be able to face himself if he turned back now and acknowledged himself less of a man than Hanno, Cortez, Pizarro, and all of the other nuts.

On the other hand, if he went on and failed he would have no self to acknowledge.

What he really wanted to do, he decided, was to go on and succeed but not if it meant getting killed.

All in all, it was an interesting problem and one that a man might fruitfully contemplate for quite some time. A few weeks' thought might well bring him the correct answer and spare him untold…

"The creature is approaching rather rapidly," the robot said.

"Well? Shoot it."

"Maybe it's harmless."

"Let's shoot first and think about all of that later."

"Shooting is not an appropriate response to all dangerous situations," the robot said.

"It is on Earth."

"It's not on Darbis IV," the robot said. "There, immobility is a much safer stratagem."

"The question is," Mishkin said, "whether this place is more like Earth or like Darbis."

"If we knew that," the robot said, "we'd really know something."

The new menace appeared to be a worm some twenty feet long, coloured orange, with black bands around each of its segments. The worm had five heads arranged in a cluster at one end. Each head had a single multifaceted eye and a deep, toothless, moist green mouth.

"Anything that big has got to be dangerous," Mishkin said.

"Not on Darbis," the robot told him. "There, the bigger they come, the nicer they are. It's the little bastards you have to watch out for."

"What do you suggest we do now?" Mishkin asked.

"Beats the hell out of me," the robot said.

The worm came to within ten feet of them. The mouths opened.

"Shoot!" Mishkin said.

The robot raised his blasters and fired directly at the worm's uplifted thorax. Several of the worm's heads blinked and looked annoyed. No other change could be observed.

The robot lifted his blasters again, but Mishkin told him to stop.

"That's not going to do it," he said. "What else do you have in mind?"

"Immobility."

"To hell with that, I think we should run like crazy."

"No time," the robot said. "Freeze!"

Mishkin forced himself to stand perfectly still as the worm's heads approached him. He shut his eyes tightly and listened to the following conversation:

"Let's eat him, huh, Vince?"

"Shaddup, Eddie, we ate a whole ormitung last night, you wanna give us indigestion?"

"I'm still hungry."

"So am I."

"Me too."

Mishkin opened his eyes and saw that the worm's five heads were talking to each other. The one named Vince was in the middle and was noticeably larger than the other heads. Vince was saying, "You guys make me sick, you and your eating! Just when I get our body in shape after working out at the gym all month, you wanna go put a belly on us and I say nix to that."

One of the heads snivelled, "We can eat anything we want whenever we want. Our Poppa, God rest his soul, said it was all of ours body and we was to share it equally."

"Poppa also said that I was to look after you kids," Vince said, "because between you all you ain't got enough brains to climb a tree. And besides, Poppa never ate strangers."

"That's true." The head turned towards Mishkin. "I'm Eddie."

The other heads also turned. "I'm Lucco."

"I'm Joe."

"I'm Chico. And that's Vince. OK, Vince, we're gonna eat him now "cause there's four of us and we're tired of you always giving orders just because you're oldest, and from now on we're going to do exactly what the hell we want to do and if you don't like it you can damned well lump it. OK, Vince?"

"Shaddap!"Vince bellowed. "If anyone does any eating around here it's going to be me."

"But how about us?" Chico whined. "Poppa said…"

"Anything I eat will be for all of you," Vince said.

"But we won't be able to tasteanything unless we eat for ourselves," Eddie said.

"Tough," Vince sneered. "I'll do the tasting for all of us."

Mishkin ventured to speak. "Excuse me, Vince…"

"Mr Pagliotelli to you," Vince said.

"I just wanted to point out that I am a form of intelligent life, and where I come from one intelligent creature does not eat another intelligent creature except under really exceptional circumstances."

"You trying to teach me manners?" Vince said. "I gotta good mind to break your back for making a remark like that. Besides, you attacked me first."

"That was before I knew you were intelligent."

"You trying to put me on?" Vince said. "Me, intelligent? I never even finished high school! Ever since Poppa died I've had to work twelve hours a day in the sheet metal shop just to keep the kids in orlotans. But at least I'm smart enough to know that I ain't smart."

"You sound pretty smart to me," Mishkin said smarmily.

"Oh, sure, I got a certain native shrewdness. I'm maybe as smart as any other uneducated Wop worm. But education-wise…"

"Formal education is frequently overrated," Mishkin pointed out.

"Don't I know it," Vince said. "But how else are you going to get along in the world?"

"It's tough," Mishkin admitted.

"You'll laugh at me when I tell you this, but what I really always wanted to do was study the violin. Isn't that funny?"

"Not at all," Mishkin said.

"Can you imagine me, big stupid Vince Pagliotelli, playing stuff from Aidaon a goddamned fiddle?»

"Why not?" Mishkin said. "I'm sure you have a talent."

"The way I see it," Vince said, "I had a dream. Then life came along full-freighted with responsibilities, and I exchanged the insubstantial gossamer fabric of vision for the coarse grey cloth of – of —"

"Bread?" Mishkin suggested.

"Duty?" asked Chico.

"Responsibility?" asked the robot.

"Naw, none of them's quite it," said Vince. "An uneducated dumbell like me oughtn't to fool around with parallel constructions."

"Perhaps you could change the key terms," the robot suggested. "Try "gossamer fabric of poesy for the coarse grey cloth of the mundane"."

Vince glared at the robot, then asked Mishkin, "Who's your wise-guy buddy?"

"He's a SPER robot," Mishkin said. "But he's on the wrong planet."

"Well, tell him to watch his mouth. I don't let no goddamned robot talk to me that way."

"Sorry about that," the robot said briskly.

"Forget it. I guess I ain't going to eat either of you. But if you want some advice you'll watch your step around here. Not everyone is as basically distractable, good-hearted, and childlike as I am. Other persons in this forest would as soon eat you as look at you.

They'd rathereat you, frankly, because you don't neither of you look so good to look at."

"What sort of things should we look out for, specifically?" Mishkin asked.

"Everything, specifically," Vince replied.

8

Mishkin and the robot thanked the good-natured Wop worm and nodded politely to his ill-mannered brothers. They moved on through the forest, for now there seemed no other way to go. Slowly they marched, and then more rapidly, and each sensed at his footsteps the sour breath and sodden cough of old mortality shuffling along behind them as usual.

The robot commented on this, but Mishkin was too preoccupied to answer.

They passed huge rough trees that peeked at them through amber eyes half-covered by green shades. After they had passed, the trees whispered about it to each other.

"A real bunch of weirdos," said a great elm.

"I think it was maybe an optical illusion," said an oak. "Especially that metal thing."

"Oh, my head," said a weeping willow. "What a night! Let me tell you about it."

Mishkin and the robot continued into the inner recesses of the deeper glooms where, wraith-like, the dim, indistinct memories of past arboreal splendours still clung in a pale miasma. (A kind of dying around the sacred shafts of vague luminescence that crept broken-backed down the branches of lachrymose trees.)

"It sure is gloomy in here," Mishkin said.

"Stuff like that generally does not affect me," the robot said. "We robots tend to unemotionality. Empathy is built into us, however, so we come to experience everything vicariously, which is the same as experiencing it legitimately in the first place."

"Huh," said Mishkin.

"Because of that, I am inclined to agree with you. It is gloomy in here. It is also spooky."

The robot was a good-hearted sort and not nearly as mechanical as his appearance would lead one to believe. Years afterward, when he was quite red with rust and his hands had the telltale cracks of metal fatigue, he would speak to the robot youngsters about Mishkin. "He was a quiet man," the robot said, "and you might have thought he was a little simpleminded. But there was a directness about him and a willingness to accept his own condition that was endearing in the extreme. Taken all in all, he was a man; we shall not see his like again."

The robot children said, "Sure, Grandfather," and went away laughing behind his back.

They were smooth and sharp and bright, and they thought that they were the only ones who had ever been modern, and it never occurred to them that others had been so before them and that others would be so after them. And if they had been told that someday they would be put back on the shelf with other pieces of discarded merchandise they would have laughed all the harder. That is the way of the young robots and no amount of programming seems able to change it.

But that was still in the far future. Now there was the robot and there was Mishkin, journeying together into the forest, both of them filled with knowledge of the most exquisitely detailed sort, none of it apropos to their situation. It was probably about this time that Mishkin came to his great realization – that knowledge is never pertinent to one's needs. What you need is always something else, and a wise man builds his life around this knowledge about the lack of usefulness of knowledge.

Mishkin worried around danger. He wanted to do the right thing when he faced danger. Ignorance of the appropriate action made him anxious. He was more afraid of appearing ridiculous than he was of dying.

"Look," he said to the robot, "we must make up our minds. We may meet a danger at any time, and we really must decide how we will handle it."

"Do you have any suggestions?" the robot asked.

"We could toss a coin," Mishkin suggested.

"That," said the robot, "is the epitome of fatalism and quite opposed to the scientific attitude we both represent. Give ourselves up to chance after all our training? It is quite unthinkable."

"I don't like it much, myself," Mishkin said, "but I think that we can agree that noplan of action is a disastrous course."

The robot said, "Perhaps we could decide each case upon its merits."

"Will we have time for that?" Mishkin asked.

"Here's the chance to find out," the robot said.

Up ahead, Mishkin saw something flat and thin and wide, like a sheet. It was coloured a mouse-grey. It floated about three feet above the ground. It was coming straight towards them, like everything else in Harmonia.

"What do you think we ought to do?" Mishkin asked.

"Damned if I know," the robot said, "I was going to ask you."

"I don't think we could outrun it."

"I don't think immobility would do any good," the robot said.

"Should we shoot it?"

"Blasters don't seem to work too well on this planet. We'd probably just get it angry."

"What if we just stroll along, minding our own business," Mishkin said. "Maybe it'll just leave us alone."

"The hope of despair," said the robot.

"Do you have any other ideas?"

"No."

"Then let's start strolling."

9

Mishkin and the robot were strolling through the forest one day in the merry, merry month of May when they happened to surprise a pair of bloodshot eyes in the merry, merry month of May.

Nothing is very funny when you're underneath.

"Stand up and be counted," Mishkin's father had said to him. So Tom Mishkin stood up to be counted, and the number was one. This was not very instructive. Mishkin never stood up to be counted again.

Let's take it now from the point of view of the monster who was approaching Mishkin.

Usually reliable sources tell us that the monster did not feel at all monstrous. The monster felt anxious. That is the way everyone feels except when they are drunk or high.

It would be good to remember that when making any strange contacts: The monster feels anxious.Now, if only you can convince him that you too, despite being a monster, also feel anxious. The sharing of anxieties is the first step in communication.

"Ouch," said Mishkin.

"What's the matter?" asked the robot.

"I stubbed my toe."

"You'll never get out of this spot like that."

"What should I do?"

"It might be best to continue strolling."

The sun beat down. The forest contained many colours. Mishkin was a complicated human being with a past and a sex life and various neuroticisms. The robot was a complicated simulacrum of a man and might just as well be considered a man. The creature who was approaching them was a complete unknown but can be presumed to have had a certain pleasurable amount of complication about him. Everything was complicated.

As Mishkin approached the monster he had various fantasies, none of which are interesting enough to record.

The monster also had various fantasies.

The robot never permitted himself fantasies. He was an old-fashioned, inner-directed, Protestant ethic type of robot, and he didn't hold with tomfoolery.

There were drops of crystal clear water trembling on the green, pouting, heart-curved lips. Actually, they weren't drops of water at all; they were decals made in some loathsome factory in Yonkers. The children had decorated the trees with them.

The monster he went astrolling. He nodded civilly to Mishkin and the robot nodded civilly to the monster as they strolled past.

The monster did a double take. "What in hell was that?" he asked.

"Beats the hell out of me," said one of the perambulatory trees, who had moved back from the north forty in hopes of making a killing on the stock exchange.

"It seems to have worked," Mishkin said.

"It usually does," the robot said, "on Darbis IV."

"Do you suppose it would usually work here on Harmonia?"

"I don't see why not. After all, if a thing is right once, it is capable of being right an infinite number of times. The actual figure is nminus one, which is a very large number indeed and contains only one possibility of error out of an infinity of correct actions."

"How often does that once come up?" Mishkin asked.

"Too damned often," the robot told him. "It really knocks hell out of the law of averages."

"Well, then," Mishkin said, "maybe your formula is wrong."

"Not a chance of it," the robot said. "The theory is right, even if it usually doesn't work out in practice."

"I suppose that's good to know," Mishkin said.

"Sure it is. It's always good to know things. Anyhow, we have another chance to test it out. Here comes another monster."

10

Not everyone in the forest was capable of taking consolation from philosophy. The raemit, for example, walked along in a fog of self-loathing. The raemit knew that he was utterly and completely alone. In part this was because the raemit was the only one of his species, which tended to reinforce his feeling of isolation. But the raemit also knew that the responsibility for alienation resides with the individual and that circumstance, no matter how apparently normative, was merely the neutral ground against which the individual worked out his own internal dramas. That was a depressing thought and also a confusing one, so the raemit walked along feeling weird and spaced out and like the only raemit on Harmonia, which it was.

"What's that?" the raemit asked himself. He stared long and hard at the two alien creatures. Then he said, "Hallucinations, yet. That's what having a sensitivity such as mine brings you."

The two alien creatures or hallucinations continued walking. The raemit quickly reviewed his entire life.

"It's all a bag of shit," the raemit concluded. "A raemit works all his life and what happens? He gets himself into trouble with the cops, his girlfriend leaves him, his wife leaves him, and then he starts seeing hallucinations. I mean, really, alien creatures,what will it be next?"