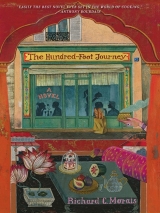

Текст книги "Richard C. Morais - The Hundred-Foot Journey"

Автор книги: Richard C. Morais

Жанр:

Новелла

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 16 (всего у книги 17 страниц)

Chapter Eighteen

March’s feeble sun retreated behind the city’s rooftop guttering. It was that time of day when the restaurant was brooding in its dismal place, that strange twilight between matinee and evening’s curtain call. The returning members of the staff were exhausted and snappish after the two-hour break, unsure whether they could once again pull themselves together for the late performance. And the dining room itself, so lively in the bright lights of the evening performance a few hours hence, appeared shopworn through the stale haze left over from lunch. It was difficult not to become despondent. Late winter shivered in the folds of the velvet drape; a bread roll, like a dead beetle, lay on its back under a chair.

I was in the kitchen as usual, sweating onions and garlic in a skillet, sliding into that trance that overtakes me when I cook. But for some reason, on this dark March evening I did not surrender myself completely, but hovered at the edge, halfway between here and there, as if I knew something momentous was about to occur.

Through the kitchen’s swinging doors—as I shook the spitting skillet—I heard the returning waiters stamping their feet in the hall. I heard the Hoover’s drone and the banging of the espresso machine as it was knocked free of old grounds by an apprentice. Bit by bit, din and duties stepped into the cold space that had occupied the restaurant just moments before: knives were sharpened, fresh linen was snapped, we heard the industrious back-and-forth of the accountant’s printer coming from upstairs. And before long, the gloom was gone.

France Soir, the evening paper, came roughly through the letter flap, clapping to the mat. It was an old habit that Jacques stubbornly would not part with, even in the digital age, and he picked the paper up and took it to the back table where his front-room staff was sitting down to a quick dinner of grilled andouillettes before the evening service began.

Newspaper under his arm, Jacques took his seat in the back, among the others. He helped himself to a portion of the chitterlings with rice, and tomato salad, reading the paper as he ate. But suddenly there was this odd gurgling in the back of Jacques’ throat and he violently dropped his fork. Before the others could find out what was the matter, however, he was up on his feet, through the door, and dashing across the dining room. And the scoundrels, enjoying nothing more than a good fight, jumped up and ran after him, hoping to witness what was looking like a first-rate row.

That was how they arrived in the kitchen: out of breath, highly agitated, slamming through the swinging doors. We in the kitchen were innocently shelling peas and dicing shallots and trimming fat, but now we froze in midchop and looked carefully about us as Jacques thrashed the air with the evening paper and bellowed.

I thought, Oh, hell, not again—for the previous night Jacques and Serge almost came to blows, as each had blamed the other for a botched order. And from the corner of my eye I could see Serge gripping the end of a lamb joint like it was a club, quite prepared to wallop Jacques or any other member of the front staff foolish enough to provoke him. I was, I don’t mind admitting it, utterly exhausted and at the end of my strength; I could not take another fiery confrontation between staff members.

“Maître! Maître!”

Jacques accusingly pointed the rolled-up newspaper at me.

“The third star! Michelin has just given you the third star!”

The first roars of excitement subsided and the staff stood three-deep around the butcher block, clinging to my every syllable as I read aloud the five-paragraph story. It was all about who was up and who was down. And then it came—the half sentence—informing le tout Paris Le Chien Méchant was among just two establishments in all France elevated to the third star.

I was stunned, numb, while a kind of Bastille Day raged all around me.

The staff banged pots and yelled and leaped about the burners. Jacques and Serge were in each other’s arms, almost like lovers in a passionate embrace, and there were tears and back-clapping and hoots of joy, all followed by more rounds of the most heartfelt handshakes.

And what was I thinking?

I cannot tell you. Not rightly.

My emotions were stirred up. Jumbled. Bittersweet, you know.

The excited staff stood in a line—the black jackets of the front room and the whites of the kitchen, like chess pieces lined up in a row—each wanting to personally congratulate me. But I was not warm, not effusive in my thanks. It might even have appeared as if I didn’t care as I observed all this joy unfolding about me from a great distance.

But consider: only twenty-eight restaurants in all France had three stars, and my journey to this point had been so long and arduous that I could not rightly believe it had finally arrived. Or, at least, I could not believe it simply on the basis of a half sentence in a mass-market evening paper. And Suzanne, near the end of the line, appeared to read my mind, for she suddenly said, ‘What if the reporter got it wrong?’

“Merde,” Serge yelled from across the kitchen, angrily pointing at her with a wooden spoon. “What is it with you, Suzanne? Always something bad to say.”

“That’s not true!”

Fortunately, at that moment we were distracted by Maxine descending from the upstairs office, wringing her hands, informing me Monsieur Barthot, the directeur général of Le Guide Michelin was on the phone and urgently wanting a word. My heart thumped as I took the spiral stairs two by two, the staff’s cries of good luck ringing in my ears as I disappeared up the turret.

I took a deep breath and picked up the phone. After the usual feigned politesse, Barthot asked, “Have you read the evening paper?”

I informed him I had, and asked straight out whether it is true we were to get the third star. “Damn papers,” he finally said. “Yes, it is true. Congratulations are in order.”

Only then did I allow the news to sink in, the enormity of it all.

Destiny had finally paid me my visit.

Monsieur Barthot rambled on about procedural matters and I struggled to stay focused on his florid talk. It seems I was expected to appear at an awards dinner in Cannes. “You know, Chef,” he said, “you are the first immigrant ever to win the third star in France. It is quite an honor.”

“Yes, yes,” I said. “Quite agree. A great honor.”

“I had to fight for you, you know. Not all my colleagues think chefs with—how can I put it?—with exotic backgrounds have the proper feel for classic French cuisine. This is a new thing for us. Mais c’est la vie. The world is changing. The guide must change as well.”

He was lying, of course, and I didn’t rightly know what to say to the man. It wasn’t Barthot who championed my cause, this I knew; he would have been among the last to vote for me. It was the inspectors’ fiercely independent reports, filed after their secret visits to the restaurant and discussed at the committee level twice a year, that undoubtedly carried the day. They were uncompromisingly dedicated to the truth as they saw it.

“Monsieur Barthot,” I finally replied, “I once again thank you and the Inspectors’ Committee. But forgive me. I must go. The restaurant opens in under two hours. You understand.”

Chapter Nineteen

That magic night in late March when I won my third star, there was, as the evening’s sitting drew to a close, an about-face on the tongue, toward the light and sweet and meltingly good, toward the pistachio madeleines and the star anise clafoutis and my famous bitter-cherry sorbet. Only a soufflé or two in the oven, only Pastry Chef Suzanne working hard at bringing up the rear. I went to her station and side by side we spooned a Beaujolais compote into crisp pie crusts just taken from the oven, a dollop of mascarpone, the final touch to my tarte au vin. And you could feel it, the heat of the kitchen, as it was notched down, that time of night when Le Chien Méchant’s stoves were silenced, one by one.

The guests outside, they slapped their linen napkins on the sides of their plates, hoisting the white flag. And I saw, from my glass portico, their legs stretched out at odd angles under the tables, upper torsos collapsed over the tabletops like meaty soufflés.

Jacques and the staff still fussed, but not so intensely. Now it was the endless subtractions, the taking away of sauce-stained platters and wine-teared crystal, the crack and crumb of bread rolls scraped from tabletops. Reviving coffees and petits fours arrived; digestives in cut crystal and a good Havana, taken gingerly from the footstool’s pocket.

“Jean-Pierre,” I called, taking off my jacket. “Bring me clean whites.”

An Australian couple seated in what we called “Siberia” saw me first, coming out of the kitchen’s swinging doors, but were unsure. As I proceeded deeper into the next salon, however, a hush swept across the room, and Jacques, looking up from the books, came forward to meet me.

Le Comte de Nancy was at his usual table to the far right side of the restaurant, with two senior partners from Lazard Frères as his guests, and he raised his liver-spotted hand in greeting, the elderly aristocrat only with great effort coming to his feet. Before I knew it, the mayor of Paris, he and his guests, they, too, were on their feet; as was Christian Lacroix, the designer, and that great Hollywood actor Johnny D., shyly tucked away in a booth with his daughter. The front-room commotion, it pulled Serge and the others from the kitchen, and they emerged to stand in the back of the dining room to join the applause. And the clapping from guests and staff alike—it was deafening—as they congratulated me on my elevation to the uppermost echelons of French haute cuisine.

What a thing, I tell you. What a thing.

That moment, that moment was the pinnacle of my life, these famous and distinguished people on their feet, my camarades de cuisine, all showing me such respect. And I remember thinking: Hmmm. Rather like this. Could get used to it.

So I stood at the center of my restaurant, taking it in, bobbing my head in return, as I gave my thanks to everyone in the room. And I tell you, as I looked out at those good people—red-faced and stuffed with my food—I suddenly felt my father’s mountainous presence at my side, beaming with pride.

Hassan, I imagined him saying. Hassan, you killed them. Very good.

Maxine came downstairs from the office to say good night. “It’s incredible, Chef,” she said, flushed with excitement. “We took seven hundred reservations this evening, the e-mails are flooding in, and the phone is still ringing—from the Americas now, as the news spreads across the Internet. We’re already booked solid through to April of next year. At this rate, we’ll have a two-year waiting list by the end of the month. And, look, you have urgent messages from Lufthansa, Tyson Foods, and Unilever. They must be calling about some business deals, non? . . . What, Chef? Why are you looking so sad?”

Lose a Michelin star and business falls off by 30 percent, but gain a star, and the business jumps 40 percent. A Lyon insurance company—selling “loss of profits” coverage to restaurateurs in danger of losing their rankings—had just proven this fact through an actuarial study.

“Ahh, Maxine. I am sad because I am thinking of Paul Verdun. My friend, he could not save himself. But he saved me.”

The young woman put her arms around my neck and whispered, “Come by for coffee later. I will wait up.”

“Thank you for the offer. Very tempting. But not tonight.”

I said good night to two waiters and Serge. He was the last to depart that evening, and only did so after we had kissed and congratulated each other one more time, and he had thumped me several more times on the back. But finally I eased shut the door, once again alone.

And that was it.

My special night gone, forever, passed into history.

With the definitive click of the back-door bolt slotting into place, I began spiraling down from the intoxicating height of the evening’s great performance. The low spirits, they rushed in, that familiar depression only a tenor coming triumphantly off the stage at La Scala could rightly understand. But that was how it was in the kitchen.

“Tant pis,” as Serge always said. Too bad.

We must take the bad with the good.

I reassured myself the windows were bolted and the pantry padlocked. Upstairs, up the turret, I made sure all the computers and my office lights were off, picking up my mobile phone and key ring from the side table as I made my way back downstairs. Dining room lights, off. One last look at the restaurant, at the faintly luminous orbs hovering in the black, the white Madagascan tablecloths shedding their last vestiges of light. Alarm, on. And then I shut the door.

The ivy around the restaurant’s barking bulldog shingle was wet with evening dew, but it had not hardened into frost, and for the first time that year I felt the balminess of an approaching spring coming through the night. It was just a hint, but it was distinctly there. I looked up Rue Valette, up the hill, as I did every night. It was my favorite view in all of Paris, looking up at the dome of Le Panthéon, caught in the yellow glow of spotlights like a soft-boiled egg in the night. And then I locked the front door.

It was the small hours, but you know, night in Paris, it’s an intoxicating affair. Always the life: an amorous middle-aged couple, arm in arm, coming down Rue Valette, as a Sorbonne medical student roared back up the hill, in the opposite direction, on a red Kawasaki. I think they felt it, too, the coming spring.

I made my contented way home, by foot, through the darkened passageways of the Quartier Latin, to my flat behind the Institut Musulman Mosque. It was not a long walk home, past Place de la Contrescarpe, down through the gauntlet of cheap North African restaurants on narrow Rue Mouffetard, a few windows to the street eerily lit by a greasy souvlaki carcass under a red light.

But somewhere down the middle of the sloping lane of Rue Mouffetard, I stopped in my tracks. I was not quite sure at first, not quite trusting my senses. I again sniffed the moist midnight air. Could it be? But there it was, the unmistakable aroma of my youth, joyously coming down a cobblestone side passage to greet me, the smell of machli ka salan, the fish curry of home, from so long ago.

So I was helpless, pulled down the dark passageway, drawn by this haunting odor of curry, to a narrow shop front at the end of the lane, where I found, squeezed between two unsavory Algerian restaurants, Madras, newly opened but now closed for the day.

A streetlamp buzzed overhead. I shielded my eyes to cut the glare of the light and peered through the restaurant’s window. The dining room was dotted with a dozen rough wooden tables, covered in paper sheets and set for the following day. Black-and-white photos of India—water-wallahs and loom weavers and crowded trains at a station—were framed simply and hung on bright yellow walls. The front lights of the restaurant were out, but the harsh fluorescent overhead tubes of the back kitchen, they were on, and I could just see what was going on down the long hall to the kitchen.

A vat of fish stew bubbled away on the stove, the special for the following day. Before the stove, a lone chef in a T-shirt and apron, sitting on a three-legged stool in the narrow back passage, his head lowered in exhaustion over a bowl of his spicy fish curry.

My hand, it rose on its own accord, hot and flat like a chapatis pushed against the glass. And I was filled with an ache that hurt, almost to breaking. A sense of loss and longing, for Mummy and India. For lovable, noisy Papa. For Madame Mallory, my teacher, and for the family I never had, sacrificed on the altar of my ambition. For my late friend Paul Verdun. For my beloved grandmother, Ammi, and her delicious pearlspot, all of which I missed, on this day, of all days.

But then, I don’t know why, standing before that little Indian restaurant, in that state of intense longing, it suddenly came to me, something Madame Mallory told me one spring morning many years ago. It was, as I look back, among the very last days I was at her restaurant.

We were in her private rooms at the top floor of Le Saule Pleureur. She wore a shawl about her shoulders and was sipping tea in her favorite bergère armchair, watching the warbling doves in the willow tree outside her window. I sat across from her, studiously absorbed in the De Re Coquinaria, taking down notes in my leather-bound book which to this day follows me everywhere. Madame Mallory returned her teacup to its saucer—with a deliberate rattle—and I looked up.

“When you leave here,” she said acidly, “you are likely to forget most of the things I have taught you. That can’t be helped. If you retain anything, however, I wish it to be this bit of advice my father gave me when I was a girl, after a famous and extremely difficult writer had just left our family hotel. ‘Gertrude,’ he said, ‘never forget a snob is a person utterly lacking in good taste.’ I myself forgot this excellent piece of advice, but I trust you will not be so foolish.”

Mallory took another sip of tea before pointedly turning those eyes on me, which were, even though she was an elderly woman, uncomfortably blue and piercing and glittery.

“I am not very good with words, but I would like to tell you that somewhere in life I lost my way, and I believe you were sent to me, perhaps by my beloved father, so that I could be restored to the world. And I thank you for this. You have made me understand that good taste is not the birthright of snobs, but a gift from God sometimes found in the most unlikely of places and in the unlikeliest of people.”

And so, as I looked at the exhausted proprietor of Madras, grabbing a bowl of simple but delicious fish stew at the end of a long day, I suddenly knew what I would tell that impossible man, the next time he told me how honored I should be, the only foreigner ever to earn a place among France’s culinary elite. I would pass on Mallory’s comment about Parisian snobs, perhaps letting the remark settle a moment before leaning forward to say, with just a touch of flying spittle, “Nah? What you think?”

But a nearby church bell chimed one a.m. and the duties of the next day beckoned, pulling at my conscience. So I took one longing last look at Madras and then unceremoniously turned on my heel, to continue on my journey down the Rue Mouffetard, leaving behind the intoxicating smells of machli ka salan, an olfactory wisp of who I was, fading fast in the Parisian night.

Chapter Twenty

Hassan? Is that you?”

From the penthouse kitchen, the clinking of dishes getting washed in the sink.

“Yes.”

“It’s amazing! Three stars!”

Mehtab had her hair done smart that day and she came into the hall, kohl-eyed like our mother, in her best silk salwar kameez, smiling up at me, arms outstretched.

“Not so bad, yaar,” I said, slipping back into the patois of our childhood.

“Oh, so proud. Oh, I wish Mummy and Papa were here. I tink I might cry.”

But she looked nowhere near to crying.

In fact, she gave me a very hard pinch.

“Ow,” I yelped.

The gold bangles up her arm jangled violently as she shook her finger. “You stinker! Why you not call and tell me? Why you embarrass me with the neighbors? I have to hear from strangers?”

“Ah, Mehtab. Wanted to, you know, but so busy, yaar. Learn just before restaurant open and phone ringing all the time and guests arriving. Every time I try and call you I have one big thing to deal with after another.”

“Huh. Just excuses.”

“So, who told you?”

Mehtab’s face suddenly softened.

She put her fingers to her lips and beckoned that I should follow.

* * *

Margaret was in the living room, sitting upright in the middle of our white leather couch, her eyes closed, her head slowly dropping back as she dozed, only to snap forward at the last moment. A hand each rested on her son and daughter, both sound asleep, both with their heads on her lap, their legs curled under the blankets that I recognized came from Mehtab’s personal chest. And I recall that the children’s faces were wiped of everything but the most profound and touching innocence.

“Aren’t they adorable?” Mehtab whispered. “And so good. Ate up all my dinner.”

The look on my sister’s face, it was the utter joy of finally having children in her home, that destiny she always thought would be hers but was never meant to be.

But then she scowled, just like Auntie, with that bitter-lemon look. “She the only one of your friends bother to tell me you get the star.”

She pinched me again, but not so hard this time.

“Brought me the paper, France Soir. Such a nice girl. And told me all about her husband, you know. What a brute. They have suffered terribly, her and the little ones . . . and why you not tell me she move to Paris?”

Luckily, at that moment, I was saved from another barrage of Mehtab mortar attacks, because Margaret opened her eyes, and when she saw us peering at her from the door, she smiled, her face sweetly lit up. She held up a finger, signaling us to wait, and she slowly, delicately extricated herself from the dangly limbs of her children, both still sound asleep.

We hugged and kissed warmly, out in the hall.

“I couldn’t believe it, Hassan. It’s so exciting.”

“Shock to me. Come out of the blue.”

I grasped both her hands and squeezed, looking into her eyes.

“Thank you Margaret, for coming here. For informing my sister.”

“We came right as soon as we heard the news. It was just so fantastic. We just had to see you and congratulate you. Immédiatement. What an incredible achievement. . . . Madame Mallory, she was right!”

“I am sure, up in heaven, she is telling Papa that right now.”

We laughed.

Mehtab, in her auntie mode, fiercely shushed us with a finger to her lips, and pointed we should go to the other side of the flat, to the kitchen counter, to talk. In the kitchen, we pulled out the stools from the marble counter, as Margaret told me how things were working out at Montparnasse, how decent Chef Piquot was, not at all a yeller and a tyrant, like so many of the other leading chefs.

“I will never forget, Hassan. We owe you everything.”

“I did nothing. I made one phone call.”

From the SieMatic fridge, I retrieved a bottle of chilled Moët et Chandon, popped the cork over the sink, and poured us glasses in amber antique flutes. Margaret, refreshed by her nap, was talkative.

“It was lovely to see your sister again, after so many years. She was so good to us, when we just showed up unannounced at the door. So kind to the children. And my, can she cook! Ooh la la. Just as well as you. She gave us dinner. Délicieuse. A spicy beef stew, thick and gooey, perfect for the chilly night. And so different from our boeuf Bourguignon.”

Mehtab, her cooking suitably relished and appreciated, was looking very regal, very aloofly pleased, even though she was pretending not to listen to our conversation. She was setting my place for my late-night snack.

“Margaret, come,” she said, pushing a dish of sweets across the counter. “You have still to try my carrot halva. And we must discuss Hassan’s party. The menu. And who we should invite.”

My sister turned to me and in a tone close to barking said, “Go. Go wash up.”

When I put my face down under the running water, the phone rang. A few moments later, the sound of padding feet, and Mehtab’s voice coming through the bathroom door.

“It’s Zainab. Pick up.”

The line crackled. Far away. Like talking under the sea.

“Oh, Hassan. They would have been so proud. Papa and Mummy and Ammi. Imagine. Three Michelin stars!”

I tried to change the subject, but she would have none of it. Had to give her all the details.

“Uday wants a word.”

Uday’s baritone boomed down the line.

“Such incredibly good news, Hassan. We’re terribly proud of you. Congratulations.”

Zainab’s husband, Uday Joshi.

No, not the Bombay restaurateur who set my father’s teeth on edge.

The son.

Uday and Zainab, the two of them, they were the talk of all Mumbai. They had turned the old Hyderabad restaurant into a pish-posh boutique hotel and restaurant chain. Very Mumbai chic. Turned out, of all of us, little Zainab was most like Papa. An empire-builder. Always with the big plans, just more competent.

I remembered that time when Uday and Zainab married in Mumbai, shortly before Papa died. It was very awkward at first, when Papa and Uday Joshi, Sr., finally met up at the wedding. Papa talked far too much, carrying on with his show-off palaver, old man Joshi looking bored, stooped and gripping the handle of a cane. But later the two aged fathers posed together for the Hello Bombay! photographer, a couple of paternal peacocks, for a wedding spread that eventually took up five pages of the popular magazine, and after that the old men both softened up and talked together late into the night.

When Papa and I met up later, he said, “That old rooster. I look much better than he does, yaar? Don’t you tink? He is very old.”

And I remember standing with Papa, late in the night, when the festivities were in full swing, as a jeweled elephant carried the newlyweds across the grass, while the white-jacketed servants, bearing aloft silver trays covered in champagne flutes, professionally threaded themselves among the twelve hundred glittering guests. And there, in the center of the main tent, a silver vessel filled with beluga, the politicians elbowing their way forward, plopping soup ladles of the caviar onto their plates, two-thousand-dollar dollops at a time.

But Papa and I just watched, standing off to the side in the shadow of the night, under a string of fairy lights, eating kulfi, the Indian ice cream, from the kulfi-wallah’s simple earthenware pots. And I remember the taste of the cold blanched almond cream as we marveled at the women’s emerald earrings. Big as plums, Papa kept on saying. Big as plums.

“We must talk business,” my sister’s husband again said down the phone. “Zainab and I, we have a business proposal that you might find interesting. Now’s the time to open tip-top French restaurants in India. There’s lots of money sloshing about. We already have financing.”

“Yes. Yes. Let’s schedule a time to talk. But not tonight. Let’s talk next week.”

“He has a very light dinner, or none at all, but always a nighttime snack after he comes home from work,” Mehtab was telling Margaret when I returned to the kitchen. “It helps him relax. And he usually has a mint tea. With a spoonful of garam masala in it. Or sometimes a bit of my vegetables. And sparkling water.”

“Ah. I know this pastry.”

“They are not from the pâtisserie, of course. I make them myself, using the recipe of his old teacher. A pistachio paste, and in the glaze, yaar, a little vanilla essence. Try it.”

“Better than Madame Mallory’s, I think. Certainly better than mine.”

My sister was so flushed with pleasure at this compliment, she had to turn back to the sink to cover up her embarrassment. I had to smile.

“Mehtab. Did anyone else ring?”

“Umar. He is going to drive the whole family down for the Three-Star Party.”

Umar still lived in Lumière, the proud owner of two local Total garages. He also had four stunning boys, and the second oldest was coming up to Paris next year, to join me in the kitchen of Le Chien Méchant. The rest of the Hajis, adrift and scattered across the globe. My younger brothers, the rascals, both chronically restless, had wandered the world for years. Mukhtar was a mobile phone software designer in Helsinki, and Arash, he was a law professor at Columbia University in New York.

“You must call all your brothers tomorrow, Hassan.”

“Mais oui,” said Margaret, lightly touching my elbow. “Your brothers must hear the fantastic news from you directly.”

Umar, my sister continued, said he would also see if Uncle Mayur was game, but he didn’t think the retirement home would allow him to make the journey to Paris, because Uncle Mayur was so wobbly on his legs these days. Uncle Mayur, eighty-three, was the last one we thought would make it this long. But when I looked back, Uncle Mayur, he never worried about anything, was always stress-free, perhaps because Auntie fretted enough for the two of them.

Mehtab patted her hair. “And what do you tink, Margaret? Who else of Hassan’s friends should we invite? What about that strange butcher with all the shops, the one who owns the chateau in Saint-Étienne?”

“Ah, mon Dieu. Hessmann. A pig.”

“Haar. I think so, too. I never know what Hassan sees in that man.”

“Put him on the list,” I said. “He’s my friend and he’s coming.”

The two women just looked at me. Blinked.

“And what do you think of the accountant? Maxine, the nervous one. You know, I think she has a crush on Hassan.”

I let them get on with it, their plots and machinations for my party, as I drifted, restless, from room to room through the flat, as if there were some unfinished business I had to attend to, but couldn’t remember what it was.

I opened the door to my study.

Mehtab had placed the copy of France Soir on my desk.

It came to me, then. At my desk, with great purpose, I picked up a pair of scissors and neatly trimmed the page-three article. I slipped the cutting into a wooden frame, leaned over, and hung the announcement of my third star on the wall.

In that hungry space.

Of generations ago.