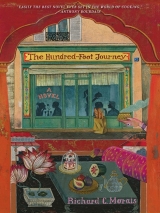

Текст книги "Richard C. Morais - The Hundred-Foot Journey"

Автор книги: Richard C. Morais

Жанр:

Новелла

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 14 (всего у книги 17 страниц)

Chapter Sixteen

Chef ?”

“Oui, Jean-Luc.”

The apprentice licked his lips nervously.

“Monsieur Serge asked me to tell you the ptarmigan have arrived.”

I looked over at the wall clock, next to the Ndebele wall hanging picked up in Zimbabwe, depicting village women roasting a quartered buffalo. There was just an hour and forty minutes before the restaurant opened for lunch.

I had been reading one of Madame Mallory’s favorite cookbooks—Margaridou: The Journal of an Auvergne Cook—but at Jean-Luc’s beckoning, I gently closed the old book shut, its simple recipes from a bygone era, and stood to put it safely away on the bookshelf.

It was, as I turned, the sight of the Credit Suisse “tombstone” in Plexiglas, the advertisement announcing the initial public offering of Recipe.com, an Internet start-up selling recipes and of which I was an outside director, that made me pause. My office, in that mote-filled light pouring in from the window, suddenly looked ridiculous to me. Wooden-and-brass plaques and awards littered every available surface in the office, the strangest of which was a gold-plated soup ladle from the Brussels-based International Soup Society. My long-cherished treasures suddenly looked like worthless bric-a-brac.

Something undeniable had happened since Paul’s death. It was as if his spiritual malaise had jumped bodies and entered me, like some flesh-eating parasite from a Hollywood horror film. I was restless, irritable, had trouble sleeping. I did not know what was going on, only that a feeling of doom was bearing down on me. And I hated it, this unfamiliar sensation, for this was not me at all. I have always been quite a sunny fellow.

But Jean-Luc was still studying me from the door frame of my office, unsure whether some other prank was about to befall him. So it was ultimately the look on the boy’s face—painful insecurity—that finally brought me out of myself.

I stood up and said, “Bien. Let us go to work, then.”

Jean-Luc led the way down the spiral staircase, and we returned to the clatter and scrape and whoosh of Le Chien Méchant’s kitchen gearing up for action; to waiters slamming through the swinging doors, polishing silver and filling cigar boxes and folding linen rosettes, their jackets off as they dashed between kitchen and dining room and back.

Chef de Cuisine Serge was on the far side of the kitchen with two sous chefs, standing over open flames. Suzanne, my pastry chef, was bent over a tray of tarts. There was excited palaver about soccer match this and that, but Jean-Luc and I made our single-minded way to the wooden crate standing in the cold kitchen, found on the counter every day in season, between late September and December, and flown in daily by game wholesalers in Moscow.

The boy forced open the wooden box with a crowbar, and together we carefully unpacked the braces of ptarmigan wrapped in tissue paper. Two other apprentices were hard at work, and I discreetly kept an eye on them as we unwrapped the birds. The girl on the far side of the sink was carefully sponging a string of red mullet with a wet cloth. I insist on this method; wash mullet under a tap and its subtle taste and color disappears down the drain. The senior apprentice brandishing a sharp knife on the meat counter—soon to don his own toque as a commis, now that we had Jean-Luc—was removing the nerves from the spine of the Charolais, the breed of French cattle that I prefer to Scottish Angus.

I took a plump ptarmigan in my hand. The arctic grouse’s white-feathered head and black eyes lolled lifelessly backward, a downy weight in my palm. With a satisfying whack of the cleaver I took off the grotesquely overdeveloped claws, and the bird’s legs disappeared into the vat of stock bubbling away on the burner to my side. I signaled to Jean-Luc that he should clean and pluck the rest.

I had to pluck forty game birds at a time when I started at Le Saule Pleureur, but happily for modern apprentices, automated plucking machines do the job quite nicely today, and I interrupted Jean-Luc to run my bird through the machine. The ptarmigan’s white feathers—still ruffled and blood-speckled from the hunter’s shot—were peeled off by the rotating rollers and then shot off on an airstream into a disposable bag to the side.

I took the plucked carcass over to the stove’s open flame to singe off the bird’s remaining quill stubble. A slice opened its crop and I took a few generous pinches of the bitter tundra herbs and berries that were still in the bird’s throat pouch. I washed the herbs at the sink, so similar in appearance to thyme, and set them aside in a ceramic bowl.

This was my trademark dish of late fall: Siberian ptarmigan, roasted with the tundra herbs taken from the bird’s own crop, and served with caramelized pears in an Armagnac sauce.

“I am not good with words, Jean-Luc. I talk best through my hands. So just watch how I do it.”

The boy nodded. I gutted the bird, washed it, and carefully blotted away all moisture with paper towels. There was some shuffling of feet but otherwise the kitchen staff was mostly silent as they concentrated on their own work or watched my demonstration. The only real noise came from the lids of copper pots rattling atop the stove, and the white-noise whir of washing machines and refrigerators and ventilating ducts in the background.

The bird’s meaty breasts came off with two clean swipes of the knife, and I seared the crimson pads of flesh in a hot pan.

A few minutes later I turned off the flame and looked up at the clock.

Just thirty minutes until we opened. The staff was watching me, waiting for the traditional presitting instructions.

I opened my mouth, but the usual platitudes, they choked.

They would not come anymore.

Because my head was flooded with torrid images, of Paul at the point of mangled death, surrounded by platters of his ornate dishes, loaded with goose fat and foie gras and rivers of his own congealing blood. I saw boarded shop fronts in the streets of Paris, the riot and bloodied heads and screaming on the Pont de la Concorde. And through these unsettling images loomed the supranaturally tanned face of Chef Mafitte, his bizarrely antiseptic lab-kitchen pumping out with great industriousness the most extravagant and decadently deconstructed meals.

And then, when I couldn’t stand it anymore, when I gave in to all these unsettling images, when I was empty and couldn’t find energy to fight and thought I might faint, they disappeared as quickly as they had come, and what poured into that empty space was a chiaroscuro vision of old Margaridou, that Auvergne cook, sitting at a farmhouse window, quietly writing her simple recipes in her journal. But when she turned her head to look directly at me, I realized with a jolt the aged woman was in fact my grandmother Ammi sitting at the upstairs window of our Napean Sea Road property in old Bombay. And she was not writing at all, but painting, and when I looked hard at the canvas in her hand, I recognized it as Gauguin’s deceptively simple painting The Meal.

“You, in the kitchen, and you in the front room, all of you. Listen up.

“Tomorrow we throw out our menu, everything we have done for the past nine years. All the heavy sauces, all the fancy dishes, they are finished. Tomorrow we begin afresh, entirely. From now on we are only going to serve simple dishes at Le Chien Méchant, dishes where the most beautiful and freshest ingredients speak for themselves.

“That means no cleverness, no fireworks, no fads. Our mission, from now on, is to make a simple boiled carrot or a clear fish broth sing. Our mission is to reduce every ingredient down to its simplest, deepest nature. We will draw on the old recipes for inspiration, yes, but we will renew them by stripping them back to their core, removing all the period embellishments and convolutions that have been added to them over time. So I want each of you to go back to your hometowns, back to your roots across France, and bring to me the best and simplest dishes from your communes, made entirely out of local ingredients. We will put all your regional dishes in a pot, play with them, and together we will come up with a menu that is delicious and refreshingly simple. No copying the heavy old brasserie dishes, no emulating the deconstructionists and the minimalists, but our own unique house built on the simplest of French truths. Remember this day, because from now on we will cook meat, fish, and vegetables in their natural essences, returning haute cuisine to cuisine de jus naturel.”

And so, just a few weeks after this radical about-face in my kitchen, the day of Paul Verdun’s memorial dinner finally arrived. I remember clearly that a saffron sun was setting in a filmy way over the Seine that November night, and France’s culinary establishment—portly men in black tie and reed-thin women in sparkly gowns—climbed the Musée d’Orsay’s stairs, the paparazzi at the ropes snapping their pictures.

All very pish-posh. Everyone who was anyone in French haute cuisine was at the memorial dinner that crystal-clear and chilly night, as even the papers reported the following day. Lists were ticked, mink coats and wraps taken, the guests making their way in stiff taffeta and soft silk to the museum’s first floor, for champagne under Monet’s Gare Saint-Lazare and Seurat’s Circus. The excitement of a Cannes Film Festival was in the air, despite the sad occasion, and the cocktail chatter, reverberating between the museum’s walls, eventually reached the roar of an airport arrivals hall. Finally, just as it was getting to be too much, a bell gonged, and a magnificent baritone announced dinner was served. The guests floated toward the grand salon, to the sea of white tables and long-stemmed irises in glass, to the Baroque murals and Rococo mirrors, to the tall windows offering a panoramic view of Paris dressed in expensive pearl strings of nighttime lights.

Anna Verdun, hair bouffant and loaded down in diamonds, sat regally at the head table in a column of blue cobalt silk.

Much had changed since I had visited her, because the silver-haired directeur général of Le Guide Michelin, Monsieur Barthot, now sat to her right, entertaining her guests with his amusing tales culled from the lives and adventures of the culinary greats.

Paul’s legal adviser—also at Madame Verdun’s table that night—had in the preceding months successfully convinced the widow that a lawsuit would drain her purse, be a source of continuous emotional turmoil, and would inevitably fail to produce the desired results. He instead recommended negotiating a face-saving arrangement directly with Monsieur Barthot.

We saw the outcome a week before Paul’s memorial dinner, when Le Guide, as we simply called it, took out full-page ads in the major papers of the country, saluting the life’s work of “our dearly departed friend, Chef Verdun.” The deal-clincher—so my gossip-gifted sister informed me—was Monsieur Barthot’s promise to deliver Chef Mafitte, who not only sang Chef Verdun’s praises in the Michelin guide’s ad, but was also at the dinner, sitting to the left of Paul’s widow and pawing her hand.

Paul would have been furious.

Anna Verdun had shunted me to table seventeen in the back of the room. As it turns out, however, the table was under one of my favorite paintings—a still life by Chardin called Gray Partridge, Pear, and Snare on Stone Table—and I took this as a particularly good omen. Besides, my seat next to the kitchen entrance was immensely practical—I could keep one eye firmly glued on the staff coming and going with the night’s fare—and the company at table seventeen was, I thought, far more entertaining than what was on offer at the more “elite” tables in the room.

We had, for example, my old friend from Montparnasse, Chef André Piquot, as cherubic and spherical and inoffensive as a boule of ice cream. Also at our table, the third-generation fishmonger Madame Elisabet. While it is true the poor woman suffered from a mild form of Tourette’s syndrome, which at times proved rather awkward, she was otherwise so very sweet, and she of course owned the formidable fish wholesaler that supplied many of the top-rated restaurants of northern France. So I was delighted to find her at our table.

To her left, meanwhile, Le Comte de Nancy Selière, my landlord on Rue Valette, so at peace with his aristocratic superiority he was beyond concerns of class and caste, and, it must be added, such a sharp-tongued curmudgeon he was not tolerated at many of the ‘finer’ tables in the room. Finally, to my left, the American expat writer James Harrison Hewitt, a food critic for Vine & Pestle, who, despite his decades living in Paris with his Egyptian boyfriend, was deeply distrusted by France’s culinary establishment because of his uncomfortably penetrating and well-informed insights into their insular world.

We all took our seats as a picture of a smiling Paul Verdun in toque was projected up onto screens. White jackets streamed from the kitchen: the amuse-bouche, a shot glass filled with a bite-sized baby octopus cooked in its “natural essence,” extra virgin olive oil from Puglia, and a single caper on a long stem. The wine—in the partisan context of French haute cuisine and endlessly commented on in the papers the following day—was considered a shot across the bow: a rare 1959 Château Musar from Lebanon.

James Hewitt was a first-rate raconteur, and the American was, like me, quietly studying the odd ménage of characters at Madame Verdun’s head table.

“You know she had to drop the lawsuit,” he said softly. “All sorts of saucy details would have emerged had she persisted.”

“Saucy details?” I replied. “Like what?”

“Paul was overextended. Poor man. His empire was about to collapse.”

It was a preposterous suggestion. Paul had been an entrepreneurial tour de force. He was, for example, the first three-star chef ever to list his holding company, Verdun et Cie, on the Paris bourse, and to use the eleven million euros of his initial public offering to completely renovate his country inn and create a string of fashionable bistros under the name Les Verdunières. It was well known he had a ten-year contract with Nestlé, creating a series of soups and dinners for the Swiss food giant’s Findus label. That contract alone was reportedly worth five million euros a year and resulted in Paul’s beaming face plastered all across the billboards and TV screens of Europe. Then there was the small fortune he earned as a consultant to Air France, plus the steady stream of fees that came from the manufacturers of linen, jams, pots and pans, cutlery, crystal, herbs, wine, oils, vinegars, kitchen cabinets, and chocolates, all of which had been eager to pay the famous chef large sums of money for the right to use his name.

So when Hewitt made that ridiculous suggestion that Paul’s empire was on the verge of collapse, I said, “Nonsense. Paul was a great businessman and ran a very profitable operation.”

Hewitt smiled painfully over his glass of Château Musar.

“Sorry, Hassan. Verdun myth. He had not a sou left. I have it on good authority Paul was leveraged up to his bald spot. Been taking out loans for years, but off the balance sheet, so none of his shareholders at the publicly traded company knew what was going on. The drop in his ranking at Gault Millau hurt—Le Coq d’Or’s bookings had been falling fast since his demotion and Air France was about to drop him as a consultant. So he was in a classic squeeze, struggling to find the cash to service his debts as his empire began to decline. No doubt about it. The loss of a Michelin star would have brought the whole thing down. I shudder even to think about it.”

I was stunned. Speechless. But a stream of waiters suddenly emerged from the kitchen, and I had to concentrate as they brought out a simple oyster in clear broth, followed shortly by a salad of Belgian endive garnished with chunks of Norwegian smoked lamb and quails’ eggs.

From the corner of my eye, I could see Chef Mafitte leaning over to whisper in Anna Verdun’s ear; she turned girlishly in his direction, laughing, her hand lifting to touch the shellacked crust of her hair.

I flashed to that time when my former girlfriend and I visited Maison Dada down in Provence. Toward the end of the meal, handsome Chef Mafitte came by our table to say hello. He was, in his whites, the bronzed and dazzling picture of a culinary celebrity, immensely charming, and I was instantly reduced to nothing in his presence. Perhaps it was this boyish subservience on my part that in some way emboldened him, for the entire time he and I talked shop, Chef Mafitte had his hand in Marie’s lap under the table, where she was heroically fighting off his inappropriate gropings.

When Mafitte finally left our table, Marie said, in her blunt Parisian way, that the great chef was nothing but a chaud lapin, which sounds rather endearing but in actual fact meant she thought he was a dangerous sex maniac. Later I learned Mafitte’s voracious appetite extended to all ages and species of viande.

I was suddenly disgusted with Anna Verdun. There was something craven and corrupt in having Paul’s artistic nemesis at her table, on this of all evenings. Where was her loyalty? But Hewitt must have read the look in my face, because he again leaned over and said, “Pity the poor woman. She’s got to get out from under the financial mess Paul has left her. I hear Chef Mafitte is considering buying Le Coq d’Or—lock, stock, and barrel—part of his expansion plans for northern France. A deal with Mafitte would certainly save whatever there is left.”

A waiter began to take away my salad plate, and I used the interruption to wave over the head caterer and whisper in his ear that he should tell Serge in the kitchen to slow down, that he was rushing the courses a bit. When I turned my attention back to the table, Hewitt was leaning forward and peering around me, a glass of the 1989 Testuz Dezaley l’Arbalete raised in salute, saying, “Isn’t that true, Eric? Chef Verdun was in trouble. Hassan doesn’t want to believe me.”

Americans have a remarkable gift for running roughshod over other nations’ caste systems, and Le Comte de Nancy Selière, normally never one to suffer fools gladly, simply raised his glass in return and said dryly, “To our dearly departed Chef Verdun. A train wreck that was, sadly, just waiting to happen.”

The poached halibut in champagne sauce was served with a 1976 Montrachet Grand Cru, Domaine de la Romanée-Conti. André Piquot and I discussed our personnel problems; he was having trouble finding a “cold kitchen” sous chef he could rely on, and I was having trouble with a waiter who seemed to be deliberately slowing down the speed with which he executed his assignments, in order, we suspected, to clock up overtime—the costly bane of the restaurateur’s existence since France had instituted the thirty-five-hour workweek.

Hewitt then regaled the entire table with a story about the time he and Le Comte de Nancy had been guests at a twelve-course meal at La Page, a “gastronomic temple” in Geneva. Apparently, the famous restaurant overlooking Lake Geneva was as severe as “a Calvinist church on Sunday,” full of pompous waiters and aged couples who didn’t say boo to each other. “There was absolutely no laughter in the room but the laughter coming from our table,” Hewitt recalled. “Am I right, Eric?”

The count grunted.

Somewhere between courses six and seven at La Page, Hewitt had a hankering for Calvados, the apple brandy from Normandy that was his preferred palate cleanser, but the La Page waiter haughtily told him that wasn’t possible. The American would have to wait until an hour or two later, after the cheeses, when a sweet brandy was appropriate. The waiter would happily bring him a liqueur then.

“Bring him his Calvados immédiatement or I will slap your face,” snapped Le Comte de Nancy. The ashen-faced waiter raced off and returned, in record time, with the requested brandy.

We all roared with laughter at this story, all but the count, who, reminded of this evening in Geneva, seemed to get angry all over again, and muttered, “Such impertinence. Such incredible impertinence.”

And while I laughed, the moment wasn’t entirely carefree, because in the back of my mind I kept thinking about what Hewitt had told me about Paul’s finances and the terrible predicament my friend had been in when he ran off the cliff. The notion that even one of the best businessmen in the field of gastronomy couldn’t make a financial success of his three-star restaurant was almost too upsetting to contemplate.

“Are you all right, Chef?” asked the sensitive Madame Elisabet, before making us all jump to attention with a “motherfuck!”

I straightened my dessert spoon and fork on the table above my plate.

“I was thinking of Paul. I just can’t believe the mess he was in. If it happened to him, it could happen to any of us.”

“Now, look, Chef, don’t mope,” said Le Comte de Nancy. “Verdun lost his way. That’s the lesson in all this. He stopped growing. End of story. I was at Le Coq d’ Or six months ago, and, I tell you, the fare, it was mediocre at best. The menu was the same as it was ten years ago. Hadn’t changed a bit. In his ambition to build his empire, Verdun took his eye off his kitchen—the source of his wealth—and then, when he was so distracted by all the noise of the circus, he took his eye off the basics of the business as well. So, yes, he was running both the creative side and the business side, very admirable, but in reality, each had only his superficial attention. He was running and running but had no focus. Any businessman will tell you that is a recipe for disaster. And sure enough, he paid the price.”

“I suppose you are right.”

“My friends, the hardest thing, when you reach a certain level, is to stay fresh, day in and day out. The world changes very fast around us, no? So, as difficult as it is, the key to success is to embrace this constant change and move with the times,” said Chef Piquot.

“That’s just blah blah. A cliché,” snapped Le Comte de Nancy.

Poor André looked as if he had just been boxed in the ears. To make matters worse, Madame Elisabet unhelpfully added, “Stupid bitch fuck!”

But Hewitt, seeing how hurt the chef was by this two-pronged attack, added, “You are right, of course, André, but I do think you have to change with the times in a way that renews your core essence, not abandons it. To change for the sake of change—without an anchor—that is mere faddishness. It will only lead you further astray.”

“Exactement,” said Le Comte de Nancy.

Normally an outsider fighting for a seat at the table occupied only by French insiders, I usually kept my opinions to myself, but that night, perhaps due to the strain of the performance, perhaps because of my recent turmoil, I blurted out, “I am just exhausted by all the ideologies. This school and that school, this theory and that theory. I have had enough of it. At my restaurant we are now only cooking local ingredients in their own juices, very simply, with one criteria: Is the food good or not? Is it fresh? Does it satisfy? Everything else is immaterial.”

Hewitt looked at me oddly, like he was seeing me for the first time, but my outburst seemed to liberate Madame Elisabet, for she added, in that sweet voice so incongruous to her blasphemous eruptions, “You are so right, Hassan. I am always reminding myself why I got into the game in the first place.” She pointed both hands, flat-palmed, out across the room. “Look at this. It’s so easy to become intoxicated by all this flimflam. Paul was seduced by the Paris bourse and all those press clips hailing him as a ‘culinary visionary.’ That is what he had to teach us—all of us—in the end. Never lose sight—”

At that moment, however, the lights were dimmed and an expectant hush fell over the tables. Then, from the back, a simple candlelight procession, followed by a dozen young waiters holding aloft silver platters loaded down with roast partridge. The room rumbled and there was a smattering of applause.

Paul’s Partridge in Mourning, as I named the dish, was the highlight of the evening, as the papers reported the following day. Up until that point, I was, I must confess, trying to hide my terror of performing before such a demanding audience, but the generous comments I received from my table suggested that my risky menu had paid off. In particular, I took great joy in seeing Le Comte de Nancy—who always called things as he saw them, was in fact incapable of an insincere remark—tearing a bread roll apart with great gusto before lunging in to mop up the last smears of juice.

“The partridge is delicious,” he said, waving his bread stub at me. “I want this on the menu at Le Chien Méchant.”

“Oui, Monsieur Le Comte.”

The dish that famously put Chef Verdun on the culinary map thirty years earlier was his poularde Alexandre Dumas. Paul filled the chicken’s cavity with julienned leeks and carrots, then surgically perforated the bird’s outer shell so truffle slices could be delicately inserted into the bird’s skin. As the bird roasted in the oven, the truffles and chicken fat melted together, their essences seeping deliciously through the meat and leaving a uniquely earthy flavor. It was Paul’s signature, a dish always found for a princely sum of 170 euros on the menu of Le Coq d’Or.

The night of his memorial, wanting to pay Paul an homage, I took the basic techniques of his poularde, and applied it to partridge, well known to be his personal favorite game bird. The result was a powerfully pungent bit of fowl, just this side of being feral. I stuffed the birds with glazed apricots—instead of julienned legumes—and then so blackened the fowl with black truffle slices inserted in their skin they looked like birds dressed for a Victorian funeral—hence the name Paul’s Partridge in Mourning. Of course, my sommelier then had the inspired idea to twin the partridge with the 1996 Côtes du Rhône Cuvée Romaine, a robust red redolent of dogs panting and on point in the lushness of a summer hunt.

Several distinguished critics and restaurateurs—including one of my idols, Chef Rouët—personally came by our table later in the evening, to congratulate me on the menu and, in particular, my interpretation of Paul’s signature dish. Even Monsieur Barthot, Le Guide Michelin directeur général, descended from the Olympian heights of the head table to shake my hand and to say, rather loftily, “Excellent, Chef. Excellent,” before striding off to speak to someone of more importance. And in that moment I finally understood why Paul had orchestrated this posthumous dinner.

I looked over to the head table, to make grateful eye contact with Anna Verdun, but Paul’s widow was at that moment looking vacantly out across the room, a smile of sorts frozen across her face, while Chef Mafitte was leaning in on her from the left, one hand under the table.

No, I would not tell her, I decided. She had enough on her plate.

Besides, it was enough that I knew why Paul had planned this evening.

The memorial dinner was not for Paul, you see, but for me. With this meal my friend had signaled to France’s culinary elite that a new gardien of classic French cuisine had burst on to the scene. I was his anointed heir. And so I think it is safe to say that before that night I was a relatively faceless figure lost among the scores of competent and talented two-star chefs all across France.

After that night, however, I was propelled to the top ranks, my good friend ensuring—even from beyond the grave—that the country’s gastronomic elite made room for a forty-two-year-old foreign-born chef he had personally chosen to protect the classic principles of France’s cuisine de campagne, which he and Madame Mallory had fought so hard to protect.