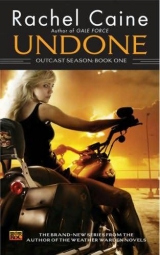

Текст книги "Undone"

Автор книги: Rachel Caine

Жанр:

Городское фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 18 страниц)

Chapter 3

I’D NEVER EXPECTEDthat Manny Rocha didn’t live close by. Human distances baffled me, but when he showed me a map of the country– country, another thing to learn; I was a citizen of the United States now, according to the paperwork that Lewis had provided me—I discovered that it was far removed from Florida. As Lewis had warned me, he wanted me well away from Joanne, David, himself, and whatever crisis loomed for them—less, I suspected, from any concern for me than a desire not to trip over me in the heat of battle.

Manny pointed to an almost square state near the center of the map. “That’s New Mexico,” he it „said. “It’s another state. We’re in Florida right now, here.” He tapped the squiggle of irregular lines on the map. “Going here.” His fingers moved a long, long way between the two. “Now, usually I’d fly, but I don’t want you freaking out. Last thing I want to do is deal with you and Homeland Security at the same time.”

Freaking out, I realized, meant “losing control.” I frowned at him. “I will not freak out.”

“Yeah, great. I still think I’d rather drive,” he said.

I looked again at the map. “How many minutes is this drive?” I was still struggling with the concepts of artificial time, but from the look on Manny’s face, I had not struggled hard enough. “Hours?”

“Days,” he said. “That’s a couple of days, lady.”

Days.Trapped in a clanking, stinking metal monster. No. “Is there no other way?”

“Like I said, we could fly, but—”

Flying. I was most comfortable in the air. “Fine.”

“You have to understand, there are rules—”

Everything had rules in the human world. Annoying. “I will not freak out.”

As Manny had supposed, I was wrong about that.

So many rules.I had no baggage, except for a leather bag to carry the identification the Wardens had given me, and a handful of currency that Manny, muttering under his breath, had withdrawn from a machine he’d called an ATM. I had watched the process carefully, then checked the plastic cards that the Wardens provided. I had one with my image imprinted on it that read at the top DRIVER’S LICENSE, which meant I could operate a motor vehicle. Not that I would ever wish to. I had a gold, shimmering card with the image of an ancient goddess on its surface.

“Credit card,” Manny explained, when I held it up. We were standing in line at the airport. “For buying things. But don’t buy things.”

“Then why did I receive one?”

“Because my bosses are crazy?”

I held up the next card.

“Yeah, that’s an ATM card. Somewhere in there, you should have information about your PIN number. That’s like a code you put into the machine. If you have the right code and the right card, you get money. Money comes to you from the Wardens. It’s compensation for the work you do for them.” Did my ears deceive me, or did Manny Rocha seem to resent that? “But you have to pay attention. You can’t pull out more money than you have in the account.”

That seemed straightforward enough. I put the ATM card, credit card, and driver’s license back into my purse, and pulled out a small dark blue booklet with pale blue pages. The inside front cover once again held my image. I stared at it for some time, but the image did not move.

“Passport,” Manny said before I asked. “You need that. Keep it out, along with your tickets.”

All around me, people were waiting. Some stood patiently, some fidgeted, some seethed. Traveling seemed to be a tremendous effort. I began to see why Manny might prefer to drive, despite the horrible, suffocating, noisy box on wheels. The journey would at least be under his control.

I watched the security process with great interest, but despite my study, when it came time for me to copy the actions of those who had gone before me, I found it clumsy and humiliating. I placed my bag in the plastic bin, which rumbled away through the machine– X-ray machine, according to Manny—and slipped off my shoes at the impatient motion from the guard and added those to another bin.

But when I walked through the portal, alarms sounded. I froze, frowning, as two large men in matching clothes came toward me.

“Back up,” one ordered. “Got any metal on you?”

Metal. I looked down at my clothing. I had a belt, yes, with a metal buckle. I removed it.

Alarms again. I felt an unfamiliar pressure in my chest. Anxiety? It was infuriating. These rules were infuriating.I had held power since before the ancestors of these humans had learned to scratch pictographs in rocks, and they were making me feel . . . afraid.

I gritted my teeth and removed my jacket when they ordered it. In my shirtsleeves, with bare feet, I walked through the portal, and no alarms sounded.

The relief was even more humiliating than the anxiety.

Manny Rocha breezed through without a pause, and stopped next to me to pull on his shoes and pick up the bags and detritus from his pockets. “Just remember. Flying was yourchoice.” He paused a second, then said without looking directly at me, “I thought you’d lose your temper.”

I almost had. “I did not.”

“Yeah. Good. Let’s keep it that way.”

I had been powerful once. Powerful enough to reduce this building to smoking ash. Instead of comforting me, that thought made me feel heavy in my skin, and helpless. Again.

I put on my shoes, belt, and jacket; grabbed my single bag; and followed Manny as he set out down the long, broad, busy hallway.

There were Djinn in the airport.

I don’t know why that came as a surprise to me; it shouldn’t have, but I had not thought there were so many of us walking the earth, much less lingering in this transient place. I waited for Manny to point them out to me, but he seemed oblivious, and when we took our seats in the area designated for our flight, I decided to open the subject.

“Djinn?” he repeated, frowning, and looked around sharply. “Where?”

Ah. So it was true; even the Wardens could not identify a Djinn in human form, if the Djinn wished to remain concealed. That meant that the humans around me, even those who had some bit of Warden ability, saw nothing when they looked at me but a tall, awkward, pale woman with untidy white hair.

No. I wasnothing but a tall, awkward, pale woman with untidy white hair. No longer a Djinn. I had to remember that.

I shifted uncomfortably in the hard seat, and tried not to breathe too deeply. Public spaces were filthy with odors, soaked with emotions. It put me on edge.

I pointed to the first Djinn I saw. “There.” He was a plain young man in a red T-shirt and jeans, carrying a backpack, but I caught the flare of his aura. When he turned my direction, I saw a flash of opal in his eyes.

Then he disappeared into the crowd.

Manny was looking at me oddly. “Who?”

There was no point in trying. He wouldn’t recognize a Djinn, not the way I would. I shook my head and shifted again restlessly. I wanted to move, to walk. To feel less caged.

The thought that I would be trapped inside of a small metal box, surrounded by humans and all their odors and noises and emotions, made me feel a little sick. Perhaps we should have driven.I could have opened a window. I understood—Manny had emphasized it to me in forceful language—that I could not do so on the aircraft.

“We got you an apartment,” he was saying. “It’s your home. You’ll stay there when you’re not working. It’s not far from my place, a couple of blocks. Got you a phone, too. You’re on your own for furniture. I’ll give you some catalogs; we get a ton of them.”

He said we.He had said that before. “You don’t live alone.”

Manny glanced at me, then down at the magazine open in his hands. “No. I’ve got a wife, Angela, and a daughter. Isabel. Ibby, for short.”

“Angela,” I repeated. “Isabel. Ibby.”

“They’ve got nothing to do with you.” He said it aggressively, as if I had trespassed on something private. “They’re not Wardens. They’re my family.”

Merely humans, then. I would have no interaction with them. “I have no interest in them,” I said, which I meant to be reassuring. Manny frowned again. “What?”

“I think I need to send you to school or something. You always this unpleasant?”

I gazed at him for a long moment without blinking. “You don’t enjoy flying.”

I had surprised him. “What makes you say—”

“It’s obvious.” I felt my lips curl into a smile. “You strike out at me, but it’s not me you fear.”

“Doesn’t mean you’re not a bitch, Cassie.”

Cassie?“My name is Cassiel.” I glowered at him. That made him smile, and the longer I glared, the wider the smile.

“Okay,” he finally said. “No nicknames. Got it.”

Our staring match was interrupted by a tinny, crackling voice from overhead. Our flight, it seemed, was ready for boarding. I rose gratefully, clutching my ticket, and began to move toward the uniformed attendant.

“Whoa,” Manny said, and grabbed me by the arm. “We’re not—”

I turned on him, snarling. “Take your hand off of me!” I couldn’t abide being touched so suddenly, with such disrespect.

Manny didn’t let go. “Hey. Easy!” His voice was soft, but sharp as a knife. “I told you, no freaking, and I wasn’t kidding. You cause a scene in here, and we both end up in trouble. Relax. I was saying that we’re not first class, so we have to wait our turn.”

There were classes among humans. I’d known there were, of course; I was not totally ignorant of power and structure. But America prided itself on being a free and equal society. I wondered who became first class, and how.

“Money,” Manny said, when I asked. He loosened his grip on me. “Sorry about grabbing, but you’re going to have to remember not to take my head off, okay?”

“Okay,” I said. It wasn’t, but I would have to find a way to make allowances for his impulsive actions.

And my own. This body seemed to have its own set of rules and behaviors, and I was not entirely comfortable in controlling its responses.

I waited in silence while the first classsection boarded—I could see no differences, in truth, between Manny and those others, so perhaps it really was a question of money—and then moved forward when he prompted me.

The hallway was narrow, chilly, and reeked of oil and metal. I coughed and tried not to breathe, but that was not possible.

When I reached the rounded door of the aircraft, I had a curious wave of anxiety. It’s so small.And so it was, not only the entrance, but the plane itself—smaller than I’d expected, tremendously fragile in its construction. I am entrusting myself to the care of humans.

“Hey,” Manny said, and put a hand on my shoulder. “Go. You’re holding up the line.”

I didn’t want to do it, but I stepped into the plane. I’d like to say it wasn’t as bad as I expected, but that would be a lie.

I survived the flight in much the same way I’d survived my fall from Djinn grace: by sheer endurance. It was not a pleasant experience. My body was prone to fits of anxiety whenever the plane shuddered in the sky, which was often. My body also constantly complained of aches, pains, discomforts, annoyances, and a persistent need to rid itself of the liquids I compulsively consumed.

When we escaped from the confinement some five hours later, I was unsteady and weak with relief. The air in the jetway seemed clean and refreshing, after breathing the filthy recycled stuff, and the spring of metal and rubber under my feet felt almost joyous.

Leaving the airport was easier by far than I’d expected—we simply walked out, into the hot, dry air. The sun was low on the="6as low horizon, and the sky . . .

... Oh, the sky.

I stopped and stared. I had seen more beautiful things as a Djinn, but never as a human, through human eyes, and the colors of the sunset woke feelings in me I had never known were possible. It made me feel small and yet, somehow, part of something vast and astonishing.

“Home sweet home,” Manny said, and grabbed my arm again. It was a credit to the beautiful display of the sunset that I did not even care. “Let’s go, Cassiel.”

We were only a few steps out of the building when a small human form ran headlong into Manny and clasped him around the knees. “Papa, Papa, Papa!”

I had not known Manny could smile that way—so full of tenderness. “Hey, Ib,” he said, and peeled the child away from his knees to lift her up. She promptly circled his neck with chubby arms, legs wrapping around his waist. A perfectly miniature person, dressed in miniature adult fashion in small blue jeans, an offensively bright shirt, and . . .

Isabel turned her face toward me and smiled, and it was as if the sun had risen new and clean, full of warmth and impartial welcome. She was a lovely child, with skin the color of caramel and eyes of a dark, warm brown. A round little face, surrounded by glossy black curls. “Who’s that, Papa?”

“That’s Cassiel,” he told her. “She’s my new friend. Say hello to her.”

Isabel studied me for a few seconds, still smiling, and then said, “Hello. My papa’s taking me for pizza.”

“Oh, your papa is, is he?” Manny shifted her weight to one hip and gave me a look that invited me to share his amusement. “Tell you what: Let me get Cassiel settled, and then we’ll see. Where’s your mom?”

The child pointed, and there, a few paces away next to a large dark red van, was an older, taller version of Isabel. She had the same long, curling hair, the same smile, but there was a distance to her. She was much more guarded.

She waved. Manny waved back. So did Isabel. “That’s Angela,” Manny said. “Guess she got off work after all.” He stopped for a moment, staring at his wife, and without looking at me, he said, “You understand, I don’t want you putting them at risk. I wasn’t planning for you to meet them on day one, but I guess that’s where we are now.”

I didn’t understand, but I knew he wanted reassurance. “I will not harm your family,” I said stiffly. In truth, they were not Wardens. Their lives meant little to me.

Manny sent me a glance, finally. “All right. Then let’s go.”

Manny had gone only a few feet when he realized I was not following, and turned back with a frown.

“Well?” he asked. “You coming or not?”

I had no choice. Manny was my Conduit, my only survival. I felt like an imposter, but it was better than being alone.

Manny and his family lived in Albuquerque, a town of hills and mountains. Humans had tamed the land, but not subdued it; there was wildness here, and power. I felt the vibration of it in the ancient mountains, in the clear blue sky above.

The structure of their house, on the other hand, was so new as to have no aetheric presence at all. “We just got it about six months ago,” Manny told me as he unlocked the door and held it open for his wife and child. Isabel skipped inside, shoes thundering on the wooden floor. “It’s small, but we like it.” He seemed strangely anxious that I like it, too.

I nodded, unsure what to say. It was a box. Walls, floors, ceilings. Cluttered with bright furniture and toys. Angela picked up some and moved them aside, but not as if she were worried about my opinion; she simply did it automatically. Isabel, seeing her mother’s actions, imitated her, picking up a doll and carrying it by one arm to drop it into a primary-colored box in the corner of the room.

I wondered if I would be expected to do that, as well.

I did not know the protocols, so I stood, watching, as Manny put down his bag and turned on a light next to the sofa. “Living room,” he said. Which I thought was a curious way to refer to it—did they not live in all the rooms? Was there a dying room? “Bedrooms through there. Kitchen. There’s a sunroom on the back, which is nice.”

Manny was nervous. Perhaps it was my stare. I looked away and wandered the room, idly trailing my fingertips over the cold, still pictures in frames. Family. Human family.

“That’s my brother,” he said. “Luis.”

He thought I was looking at the picture that my fingers were touching. I picked up the frame and saw that it held the image of a man, handsome, a little younger than Manny. A stronger jaw, but kind eyes.

“He’s a Warden, too,” Manny said. “You’ll meet him later, maybe. He’s out in Florida right now.”

I put the photo down. “I would like to go now,” I said, which I thought was a polite way to request an end to this. Evidently not. Manny frowned at me.

“You want something to eat first? You do want to eat, right?”

Did I? I supposed I did. Djinn in human form seemed to emulate all human functions equally, and my stomach was growling in frustration. I hadn’t yet mastered the knack of anticipating its needs.

I nodded.

Angela, who’d said very little, patted her daughter on the head and sent her scampering off to play before turning to me. I was struck by her again—a quiet, controlled woman, strong. So closely guarded. “Manny tells me you’re not human,” she said. “Is that right?”

I cocked my head. “I was not born human. I seem to be human enough now.”

Human enough.A frightening statement.

“All right,” Angela said. “I’ve seen Djinn before. I know they’re dangerous. Let me make something clear to you—if you hurt my husband, if you even thinkabout hurting my daughter, I’ll kill you. Understand?”

Manny looked taken aback. Angela’s dark eyes remained steady, fixed on mine, and I sensed nothing from her but sincerity.

“I understand,” I said, and searched for something else to say. Human words seemed clumsy to me. Ridiculously inappropriate to what I wanted to communicate. “I will make mistakes. I cannot help that.”

Her fierce stare softened a bit. “Mistakes are okay,” she said. “But don’t make them twice. And don’t you dare make them with my daughter.”

I inclined my head.

“Now,” she said. “How do you feel about enchiladas?”

“Neutral,” I said, “since I don’t know what they are.”

Angela gave me her first real smile. “Then you’re in for a treat.”

“Or not,” Manny said, “if you don’t like hot sauce.”

She hit him. It was, I realized, a playful blow, not an angry one, and I was surprised at my physical reaction, which was an impulse to reach out and stay her hand.

I had wanted to defend him. Why? Because he was my Conduit. My life source.

I hadn’t anticipated that at all.

I did not like hot sauce, which made Isabel laugh until tears rolled down her cheeks. She scooped up spoonfuls of the spice and ate them to show me how silly I was.

I could not be bested by a mere child. I continued to try, choking on the burn, until at last Angela took pity on me and removed it from the table. Isabel pouted until her father tickled her into laughter again.

It was a quiet meal—quieter than I suspected was their normal case. “When do we begin our duties?” I finally asked, after consuming several glasses of iced tea that Angela provided.

“Tomorrow,” Manny said. “Unless there’s an emergency, which I hope there isn’t.” He stood up, picked up his plate and mine, and carried them into the kitchen. “I’ll take you home now,” he called back.

Isabel ran around the table and—to my shock—crawled up into my lap. The warm, real weight of her was surprising. I looked down at her upturned face, at her smile, and frowned in puzzlement. “What do you want?” I asked her. Angela made a strangled sound of protest and rose from her chair, but I extended a hand to stop her. “Isabel?”

“A hug,” Isabel said. “You’re funny, lady.”

I thought that was quite likely true, from her miniature perspective.

I was unaccustomed to hugs, but she was an adequate instructor. She took my arms and fitted them around her small body. “Tighter!” she commanded. I dutifully squeezed, well aware of how fragile her bones were beneath the skin.

When she began to squirm, I let go. She almost toppled from my lap, and I grabbed her to steady her.

Isabel giggled, and it was as warm as sunlight.

This is a child. A young soul. A blank slate.I had never met one before, and it was oddly . . . freeing.

“That’s enough,” Angela said, and grabbed Isabel from my lap. “You need to learn some manners, mija.”

“She’s sad,” Isabel protested. “I wanted to make her smile!”

Manny came back from the kitchen. His eyes darted from Angela holding his daughter in a protective embrace, to me sitting quietly in my chair. I was not smiling. In truth, I could have, but I knew it would ring false to the child.

“Not yet, Isabel,” I told her. “Maybe later. But—thank you for the hug.”

I meant it. She had reached out to me, and although it should not have mattered to me . . . it did.

Manny broke the silence by picking up his car keys from the table and saying, in a carefully bland tone, “Let’s get you home.”

Home.

It was another box. It was filled with odors, of course—choking detergent where the carpets had been recently cleaned, paint reeking from the newly retouched walls. Aside from the odors, the room was empty save for a single small cot, made up with sheets, blanket, and pillow. A single small folding table. A single small lamp.

I liked the simplicity of it.

“Yeah,” Manny said, and juggled keys in his hand for a second before tossing them to me. I snatched them out of the air without looking. “Cozy, I know. Sorry, we didn’t have time to get things for you, and I figured you’d want to pick furniture and stuff yourself.”

He was apologizing. How odd.

“It’s fine,” I said. I threw open the nearest window and took in a breath of the air that rolled over the sill, redolent of sage and high mountain spaces.

“I guess—I’ll bring over some catalogs tomorrow. You can pick what you want. Clothes, too. You want Angela to go with you to find things?”

I looked down at myself. “What’s wrong with what I have?”

He blinked. “Nothing. Uh, you can’t wear the same thing all the time.”

I knew that. “I bought several copies of the same clothing. I know clothes must be changed and laundered.”

“But—everything you bought is the same?”

“Yes.”

He shook his head. “You are not a normal girl.”

I was not a girl.But I assumed he meant it in a figurative sense, and allowed it to pass.

Manny laid out the contents of a folder on the table. “Checkbook. Remember what I said about the ATM, and how you can only pull out what you have in the account? Same thing here. Just because you have checks left, that doesn’t mean you can keep on writing them. Here’s your phone number. Rings to this cell phone, so you should memorize it.” He pulled a small pink device from his pocket. “Sorry about the color; pink was all I could get. Last-minute.”

I liked pink. “It’s fine.” I took the machine in my hands and felt the energy coursing through it. My Djinn senses were blunted, but in close proximity, I could still feel the broad strokes of its engineering. “How does it work?”

He showed me. I called his home, explained to Angela that we were testing my cell phone, and hung up.

“We usually say good-bye,” Manny said dryly.

“Why?”

“Same reason we do most things. Because it’s polite.”

I was starting to see that. I slid the small pink phone into my pocket. “Manny.”

I had not said his name before, and it drew his attention, with a hint of anxiety. “Yes?”

“I—” My throat threatened to close around the words, but how could I survive if I could not acknowledge this? “I need—”

He understood without more being said, and extended his hand to me. I took it, cool fingers closing on warmer ones, and reached out for power.

It flowed through him in a thick golden stream, slow and sweet as honey. Not nearly as powerful as what Lewis had given me, and I sensed that it would not sustain me as long, but good nevertheless. I took in a deep breath as the warmth infused me, as the world flared into auras and a brief, tantalizing glimpse of the worlds beyond, and then steadied back into human terms.

It wasn’t easy to do it, but I let go.

Manny staggered. I grabbed his arm and guided him to the cot, where he sat and leaned forward, breathing hard. “I am sorry,” I said. “Did I—”

“No.” His voice sounded rough, and he didn’t look at me directly. “No, I’m fine. You did fine. It’s just—it feels—”

“Bad,” I supplied soberly. He raised his head, and I was surprised by the glitter in his eyes.

“No. It feels good.”

Oh.

That, I realized, could be extraordinarily dangerous for us both.

Manny left quickly after, reminding me to lock the door. I did, flimsy as the barrier was, and wandered through my apartment. It was indeed small—a “living” area, a kitchen, a second empty room, and a bath. I opened all the windows. Humans enjoyed living in boxes. I did not.

For the first time since falling into human flesh, I was alone. Truly alone.

I sat cross-legged on the floor, eyes shut, and tried to remember what it had felt like to be a Djinn. The memories faded so quickly, anchored in skin. The power from Manny resonated inside, a slow and constant rush, and for some time, nothing intruded.

Until I felt the world shift.

Something had happened, subtle and vile, on the edges of my awareness. It was not in the air—there were Wardens at work, molding the forces there, but all was well. Fire, then? No, I sensed nothing but silence from that quarter.

The vile thing was happening to a living creature, and so it whispered through the power Manny had granted me.

And it was happening here.

I shot to my feet, eyes opening, and cast about for any sense of direction. Yes, there, there, to my right and not far away . . .

I unlocked and opened the door and stepped out on the landing my apartment shared with two others. The pulse was weak now, the life fading.

I descended the two flights of stairs at a run, arrived at ground level, and turned the corner.

A child lay on the ground, with a knot of other children around him. No one was touching him, and I got no sense of malice. Only confusion, and a dawning awareness of something wrong.

There was a machine next to him—a bicycle.

He had fallen.

“Move,” I ordered the children, and they scattered like bright birds. I knelt next to the boy, my hands moving slowly above him, sensing the rightness of his body, and then the wrongness in his skull.

The bone was broken. The brain—

“Get his people,” I said, intent on the task before me.

“What?”

“His father! His mother!” My brain struggled to parse words. “Parents.”

Two of the children ran, shouting at the top of their lungs. I slid my hand carefully behind the boy’s head, and under the feather-soft hair I felt the depression where he’d struck the curb. Blood flooded warm across my fingers.

I needed Manny, but he was away, and I was alone.

The Djinn part of me said, It is an accident. It is the way of living things.And the Djinn part of me was content to let it be so.

But the human part, the human part screamed in frustration, too urgent to ignore.

I pulled from the reserve of power inside and poured it through my fingertips. Of all that the Djinn knew, we knew this—the template of things. We could build, we could destroy . . . and we could, on occasion, heal, if we held enough power inside, and the injury was fresh and contained.

I felt the bone shift, and the boy screamed. The sound pierced me like cold metal, but I gritted my teeth and kept focusing on my work, sealing the bone together. I concentrated then on reducing the swelling of his injured brain tissues. The cut in the scalp was stubborn, and continued to leak red despite my commands.

Human hands closed around my shoulders and yanked me away from the shrieking child. I fell backward, surprised.

A human man was looming above me, face dark red with rage, a fist clenched. “What are you doing to my kid?” he shouted.

The boy squirmed away from me, got to his short legs and hurried to his father’s protection, wrapping his arms around the man’s waist. I remembered Isabel grabbing on to Manny’s knees, and the fierce love and protective instinct I’d sensed between them.

“I did not hurt him,” I said. I didn’t move. Violence hung like a black cloud around the man, and any provocation could unleash the storm. “He fell from his bicycle. He struck his head.”

The words had the desired effect, as did my calm tone and direct gaze. The man’s posture shifted, his fist relaxed, and he looked down at his child. He lifted the boy in his arms and touched the back of the small head.

His fingers came away bloody. “My God—”

“You should see a doctor,” I said. Not that the child needed one, but I thought it sounded like a human thing to say. “I don’t think he’s hurt badly, but—”

The boy began to cry, wails of pain and fright, and buried his face in his father’s chest. The man stared at me for a moment, then nodded once, a dry sort of thanks, before carrying his child away.

One of the other children grabbed the bicycle and wheeled it after them. One wheel wobbled badly.

I sat there breathing hard, blood on my hands, blood cooling in the gutter, and wondered what I had just done. I’d reacted virtually without thinking. I’d spent my precious hoard of energy almost down to the last trickle, and I knew that I would have continued to give until the well ran dry, once I had engaged in the battle for the child’s life.

That frightened me. Djinn were not so careless, nor so caring of others. He was human. Humans die.That was the Djinn philosophy, and it was true.

Yet I had not even once thought of withholding my help.

I got up, sore and tired, and went back to my apartment to wash and sleep, and worry about what was happening to me.

“You what?” I had not expected Manny to be angry, but he clearly was; his face was darkening in much the same way as the boy’s father’s had when he’d been contemplating violence. “How could you be so damn careless? You don’t know what you’re doing. You’re not a healer—you can’t just—” He got his temper under control by taking several slow, deep breaths. “How’s the kid?”

“I don’t know.”

“Great. Just great. Do you have any idea how much trouble you could have been in? What if the kid had died on you? Hell, what if he died later?”

“I didn’t cause his injury,” I said, affronted. We were standing in the living area of my apartment, and Manny had brought two cups of coffee—a morning ritual, he’d assured me. It was a kind gesture, but he’d done it before I had told him of the child and my actions.

The coffee sat forgotten on the table now.

“Maybe not, but you could have gotten tied up with all kinds of questions, and the police—” Manny pressed a hand to his forehead. “Damn. What am I saying? It might not have been smart, but I’d have done the same thing. I couldn’t have ignored it, either. But I have training.You don’t, Cassiel. You can’t just—jump in. Especially not without me, okay?”