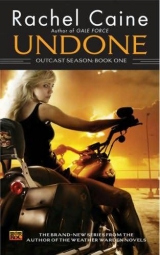

Текст книги "Undone"

Автор книги: Rachel Caine

Жанр:

Городское фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 11 (всего у книги 18 страниц)

I was almost running when I reached the front door.

I stood in the stillness of the evening, watching the last rays of the sun fade behind mountains, and breathing in convulsive gasps.

“Hurts, doesn’t it?” someone said from behind me. I turned. I’d heard—sensed—no approach, neither human nor Djinn, and for a moment I saw nothing except shadows.

Then he stepped forward into the fading light. I had not known him in human form, but I recognized the Djinn essence of him immediately. He was a brilliant flame on the aetheric, a burst that exploded out in all directions and immediately hushed itself into utter stillness.

His name was Jonathan, and he was dead.

I fell to my knees. I didn’t mean to do so, but surprise and awe made it inevitable. I’m imagining this,I thought. Jonathan is dead and gone.

“Yeah, you keep on telling yourself that, Cassie. Can I call you Cassie? Ah, hell, I’m going to, so get used to it,” he said. He looked very, very human at the moment—tall, lean, comfortable in the skin he wore. His hair glinted silver, and his eyes—his eyes were as dark as the hidden moon. “Guys like me don’t exactly die. We sort of—get promoted.”

Jonathan had held the reins to power for all the Djinn for thousands of years. I had not loved him, but I hadrespected him—if nothing else, because he had commanded respect from Ashan, and Ashan had never been stupid enough to directly challenge him. There was comfort in Jonathan, and there was also dangerous intensity, cleverly concealed by his all-too-human manner.

But he was dead.He had to be dead. We had all felt it. His passing had shattered the entire Djinn world into pieces.

“I don’t—” My voice sounded very odd. “I don’t understand. You can’t be here—”

He flipped that away with a casual gesture. “Yeah, not staying, just passing through. Got things to do. So. How’s the world? Never mind, I know the answer. Always teetering on the verge of disaster, right?” He studied me for a second, and extended his hand. “Get up, I don’t like people on their knees.”

When I accepted the touch of his hand, it felt real. Warm and human. I held it for a moment too long before I dropped it. “Everyone believes you dead.”

“Good. Meant that, actually. It was time for me to move on, and there was no way to do it without giving up my spot in the great organizational tree of life. Like I said, I’m just passing through, so I’ve got no stake in things anymore. But I thought I’d drop in to say hello.”

“Why?”

“Why?” he echoed, and his eyebrows quirked up. “Yeah, I see your point; we weren’t exactly close. I was the boss, and I was too human for your taste. We call that irony, by the way, down here in the dirt.” He let that sink in for a moment, then smiled. “You realized what you’ve been given yet?”

“Given,” I repeated, and I heard flat anger in my voice. “What have I been given?” Everything I s” E"1e had once possessed had been ripped away from me. I’d been givennothing.

From his thin-edged smile, he knew what I was thinking. “You’ve been given a chance.”

“Chance. What chance? I have been cast out, crippled, forced into human skin. I’m hunted and despised. What chanceis this?”

“Something most Djinn never get,” said Jonathan, who had been born in mortal flesh only a few thousand years ago, and yet seemed far older than I. “A chance to learn something completely new. A chance to shed your old life and form yourself in a different body, a different shape, a different direction. You’re a blank slate, Cassiel, that’s your chance.” He didn’t blink, and I saw the flicker of stars in his eyes, endless galaxies of them, an eternity of possibilities. “Or just a chance to screw it all up, all over again. Anyway. You’re here for a reason.”

“I’m here because Ashan cast me out.”

He shook his head. “Something bigger than Ashan is in play, Peaches. You’ll figure it out. You always did have logic on your side, even if you were as cold as space. You have a battle ahead of you. Just thought I’d shake your hand while I could, and tell you good luck.”

Something rippled in the sky above us, like heat above a road, and Jonathan looked up sharply. His human body flared into light, pure white light, and I sensed the flash of steel-sharp wings as I covered my eyes.

I could see him even through closed lids and concealing fingers—a man-shaped bonfire, coursing with energies I couldn’t touch, couldn’t even identify.

Jonathan had gone far beyond the Djinn, into something that was legend even to us.

“Got battles of my own to fight,” his voice said, in a whisper that came shockingly close to my ear. “Think about what I said, Cassiel. Think about your chance. Remember how it feels to feel. It’s important.”

The light intensified into a burning pressure on my skin, and I turned my back, crying out, as those mighty wings carried the being who had once been the greatest of the Djinn up, out, away.

“Cassiel?”

Luis’s voice. I whirled, shaking, and saw him standing in the doorway, watching me with unmistakable concern. There were marks of tears on his face, but he seemed . . . peaceful.

“Something wrong?” he asked. He hadn’t seen.

Jonathan wasn’t visible, not to him.

I couldn’t begin to explain. I shook my head and wrapped my arms around myself, trying to control the chill I felt. I had been in the presence of something so great that I’d felt so small beside it, and it made me wonder—it forced the question of what else the Djinn didn’t know, couldn’t imagine.

Of what I had once been, and might still become. A chance, he’d said. But a chance to be what? Do what?

“It’s okay,” Luis said, and put his hand on my shoulder. “It’s good that you cared about them.”

Manny. Angela. He thought my tears were for them—and, in a way, they were, for all the chances wasted, for all that was unknown.

I took in a deep breath and nodded. “I did,” I said, and heard the surprise in my voice. “I did care.”

Luis put his arm around my shoulders and steered me back into the funeral home, and with his hand in mine, I went to look for the last time on the first two human friends I had known.

I went to say good-bye.

I was surprised by how many people came to the viewing. Greta, the Fire Warden with the scarred face, came to pay her respects and talk quietly with Luis for a moment. She glanced toward where I sat at the back of the room, and for an instant I thought she would speak to me, but she changed course and shook hands instead with Sylvia, who sat remote and quiet near her daughter’s coffin.

Some came with flowers. Some cried. All felt uncomfortable here, in the presence of such massive change.

No one spoke to me.

At eight o’clock, the funeral director with the sad face came to me to whisper that it was time to close the viewing.

Luis was shaking hands with the last few visitors when the doors at the back opened again, and five young men walked in—Hispanic, dressed in casual, sloppy clothing. Glaring colors, baggy blue jeans topped by oversized sports team jackets, all for either UNLV or the San Francisco 49ers.

Four of them were nothing: followers. Killers, most assuredly, with jet-black eyes and no hint of conscience behind them.

But it was the one in front I watched.

He was the shortest of the five, slight of build, with a smooth, empty face and the coldest eyes I had seen in a human. Like the others, he had tattoos covering his neck and arms. He was ten years younger than Luis, perhaps more, but there was something unmistakably dangerous about him.

Luis had frozen into stillness at the first sight of the intruders, and now he moved only to keep facing them as they strolled past Sylvia, the funeral director, and the two or three remaining mourners. Luis flicked his gaze quickly to me, and in that look I read a very definite command. I rose from my seat and glided to the others in the room, and gently but without hesitation hurried them toward the doors. Sylvia frowned thunderously at me, but she also understood that something was very wrong.

I closed the doors and locked them from the inside, turned, and crossed my arms over my chest. Three of the newcomers were watching me, assessing what risk I posed; two of them immediately dismissed me. The last of them—smarter than the rest, I thought—continued to keep part of his attention on me.

“Hola,”the young leader said to Luis, and bent over Manny’s casket to stare. “Holy shit, this your brother? Doesn’t look much like you. Then again, the makeup probably don’t help. Makes him look like a puto. A dead one. Pinche carbon.”

Luis didn’t move, didn’t betray even by a flicker the anger I knew he felt. I could feel it coming off him like heat from a furnace.

“Show some respect,” he said. “Leave.”

“Respect?” The boy turned slowly in Luis’s direction, and his thin smile grew even tighter. “You want to talk to me about respect, Ene? You screwed my brother. You ratted him out. You got nothing to say about respect.”

“Whatever I did to your brother, you killed mine,” Luis said. “It’s enough. Get out and let us bury them in peace.”

The boy sprawled himself over two chairs, completely at ease, and put his feet up on the coffin. “Fuck you and your brother,” he said. “We were aiming for you.”

Two of the men slipped guns free of their waistbands and held them at their sides. Luis locked eyes with me, and I pushed away from the door.

“My friend asked you to leave,” I said. “Please comply.”

“Please what? Who is this pasty-faced gringabitch?” The boy didn’t wait to hear Luis’s response. “Never mind. Just kill her.”

The men were turning toward me when I weakened the metal chairs the boy-leader was sitting on. He toppled to the carpet, cursing, and Luis moved forward, grabbed another chair, and hit the first man to point the gun toward me in the back of the head, with stunning force.

I took a running leap and slammed my body into the midsection of the next man, ripped the gun from his hand, and threw it toward Luis. It didn’t require much power to disrupt the electrical impulses within the brain of the third man, an interruption just long enough to make him stagger and fall. Luis jumped him and recovered that gun, as well, while I moved to take down the last.

In seconds, it was done. Most of the men were on the floor, their guns in Luis’s hands or pockets, and the boy was just struggling up to his knees to find one of the guns aimed directly at him, along with Luis’s deadly stare.

He froze.

Luis thumbed back the hammer on the revolver he held. “You need to get your ass out of here before I forget my manners,” he said. “Your brother got what he deserved. Mine didn’t. You want to keep on going to war, I’ll bring it, and you’ll be the first one down. Good thing you’re already in a funeral home. Saves time.”

“Shoot me,” the boy growled. “You better shoot me, ’cause if you don’t, you got no idea what we’re going to do to you. No place you can go, no place you can hide. You oryour piece of shit family. Next time we get the kid, too.”

Heat flared inside me, sticky and tornado strong, and it was all I could do not to take hold of the boy and take him apart, one bloody scream at a time.

Luis sent me a warning look, one full of unmistakable command to stay still. “Watch them,” he ordered, and jerked his chin toward the other men. He tossed me one of the guns. I plucked it from the air and aimed it at the group of angry, hurting men in front of us. The urge to pull the trigger was very, very strong, and they must have sensed their death in the air, because none of them moved.

Luis put the gun he held away in the waistband of his pants. “You got them, Cassiel?”

“Yes,” I said softly. “What are you doing?”

“Breaking the law.”

I felt the storm of power, even though I was on the edges of it; the gravitational pull of it focused on the boy. Luis seemed to hover, almost floating in the strong currents of it, and then he lunged.

He put his hands on the boy’s slicked-back hair and his thumbs on the high forehead. The boy opened his mouth, but no scream emerged.

When his knees gave way, Luis followed him down to the floor, still holding the boy’s head. Luis’s eyes were almost black with power and rage. I kept my focus on the other men. As they realized something was happening to their leader, they decided to rush me. I sank their feet into the concrete floor, and laughed softly as I watched them flail and curse.

Whatever Luis was doing spilled over, out, traveling in a wave over the men and sending them slumped to the floor. When that wave finally lapped against me, I felt my senses slide toward darkness. I took a step back and braced myself against the door.

It receded. I blinked away the sparkling afterimages.

All the men were down. As I watched, Luis let go of the boy and went to each of the others, one by one, to clamp his fingers down on their skulls and do– something.

It took long, long minutes, and I felt his power failing on the last of them. He finished and climbed slowly, painfully to his feet, then collapsed into one of the folding chairs.

I edged around the fallen men—still not moving—and crouched down next to him. The metal of the gun felt heavy and cold in my hand.

“What did you do?” I asked.

“Changed their minds,” he said. “Literally. Wardens can put me away for pulling that kind of shit, but if I didn’t do something, they’d keep coming. They’d come for Isabel, and I couldn’t let that happen. It was that or kill them, and keep on killing the next bunch, and the next. Anyway, like I said, the Wardens got more to worry about than chasing down rule breakers.”

He sounded exhausted. I placed a hand gently on his shoulder, careful not to draw any more of his strength away.

“They’re not dead?” I asked. They weren’t moving.

“Asleep. They’ll wake up in the next few minutes. When they do, they won’t remember much. Lolly—that’s the punk-ass son of a bitch in charge of the Norteños around here—will only remember that we’re even now. Life for a life.” Luis wiped sweat from his forehead with a trembling hand. “And he’ll feel guilty. About Manny and Angela.”

“You can do that?”

“Not officially, I can’t.” He gestured, and I helped him lever himself upright. “Let’s get out of here.”

I glanced back as I shut the door to the room. The young leader, Lolly, had gotten to his hands and knees. I was afraid for a moment that he would turn and see me and remember, but he seemed transfixed by the coffins that stood just a few feet away.

He stood and walked to Angela, and I saw his hands grip the wooden side. His shoulders began to shake. I couldn’t imagine that he had shed tears for the dead in a very long time.

It must have hurt.

I was glad.

Chapter 11

WHAT LUIS HADjust done was a grave breach of the rules of the Wardens, and I understood why; Earth Wardens—the truly powerful ones—could manipulate memory. If it was done subtly enough, the victim might never suspect anything had happened at all.

It was a power that was fearfully easy to abuse, and difficult to detect. Under normal circumstances, I thought that Luis would never have done such a thing, but now, with the Wardens either withdrawn to their own affairs or potential threats . . . he couldn’t afford to rely on them for help.

Or me.

“Why didn’t you kill them?” I asked Luis. We were out of earshot of Sylvia and the funeral director, who were near the door. Luis shook his head. He was moving slowly, concentrating on the steady motion of his feet, as if it was the most difficult thing in the world at the moment.

“It’s a pride thing. You kill a Norteño, you get killed, or everybody near you does. There’s no end once you start that. It can roll on for years. Wipe out whole families.”

Blood feuds. One of the common threads of human culture, this inability to forget or forgive. It was something they had in common with the Djinn. When I had heard the boy speak of hurting Isabel, I had almost killed him. I wouldn’t have hesitated if Luis hadn’t been there. I’d have simply ended the threat, with no regard for the consequences. I would have walked away from the resulting war with no thought of guilt.

I had to admit to myself that Luis’s way was likely better.

The funeral director stepped into our path and said, in his low, gentle voice, “Is everything all right, Mr. Rocha?”

“Everything’s fine,” Luis said hoarsely. “My friends got a little carried away by their grief. I’ll pay for the damages.”

The funeral director’s eyes widened, and he moved off down the hall with what might have been unseemly haste. Luis watched him go.

“Another reason not to kill anybody,” he said. “Considering the room’s booked in my name.”

Sylvia stood by the exit, looking sad and angry. She was restlessly crumpling a tissue in her hands, over and over, and she sent Luis a filthy look as we approached.

I tried to remember that she had lost a child, but in that moment, it was difficult.

“You and your friends,” she said in a low, vicious tone, “had better not show your faces at my daughter’s funeral. God help you if you do.”

“Sylvia—”

Her eyes glittered, but the tears in them seemed more like armor than grief. “You brought the Norteños here? And then you let them walk away? What kind of a man are you, you don’t defend your own?”

She slammed open the door and stalked away. Luis hurried after her—as much as he was capable at the moment—and opened the passenger’s door of the pickup truck. He had to lift her up on the step.

She did not appear grateful.

It was a stiff, silent drive home, with Sylvia sitting rigid between us. In the passing flare of headlights, her expression remained remote and furious. She put away the handkerchief and took out a set of black, polished beads. She kissed the silver crucifix that dangled from it, and then began to work the beds through her fingers, lips moving silently. Rosary beads. I was surprised the custom had not changed from so long ago.

Luis seemed to have no trouble navigating, but I could sense his weariness. He yawned hugely as he parked the big, black truck in front of Sylvia’s house, which blazed with warm light, and opened his driver’s-side door to descend.

I hopped out and extended my hands to Sylvia. She frowned at me, and then evidently decided that I was less objectionable to her at the moment than Luis.

I lifted her effortlessly and set her feet on the concrete sidewalk. She stepped back, momentarily too amazed to frown, and Luis rounded the hood of the truck. He looked from Sylvia to me and sighed.

“Thanks,” he told me. Not as if he meant it. “Sylvia, I’d like to say good night to Isabel. If you don’t mind.” He hated asking, but seemed to recognize that insisting would only cause the woman to stand more firmly in his way.

Sylvia sent us another distrustful look, and grudgingly nodded. “Don’t wake her up if she’s asleep,” she said. “It’s hard enough for her, with the bad dreams.”

Sylvia’s sister Veronica was in the living room, knitting in the glow of the softly playing television set. She stood up to give Sylvia a hug, and then a slightly more restrained one to Luis. None for me, but Veronica—a large, grandmotherly woman with a kinder face than her sister—nodded and smiled instead.

“She’s been very quiet,” Veronica said. “I don’t think she woke up at all.”

Luis moved down the hall, leaving Sylvia to whisper with her sister, and as he reached Isabel’s door, I hesitated.

“Stop,” I whispered. Luis paused, hand in the air an inch from the knob.

“What?”

I didn’t know. There was a feeling—a wrongness. Nothing I could identify, either in the human world or on the aetheric. It was almost as if something had been here and gone, leaving only its acrid, bitter aetheric scent.

“You had a Warden watching the house?”

“Ma’at, like I told you. Yeah, of course.”

I shoved Luis out of the way and opened the door myself.

There was no immediate terror leaping to confront me; the room was as we’d left it, only darker. A sparkling night-light glimmered softly against the far wall, casting pink radiance into the corner and across the bed.

The aura was stronger here. Don’t scare the child,I told myself, and forced myself to move slowly and softly to the bed.

She was a featureless lump beneath the covers. The pink light played out its endless soothing loop, catching the shadows and creases of the blankets.

I slowly pulled them down, and heard Luis’s gasp.

The bed held only a stuffed pillow and a rag doll, whose black yarn hair spilled out over the pillow. I put my hand in the hollow where Isabel had been. “Cold,” I said. “She’s been gone a long time.” Perhaps since the first time Veronica had checked on her. I sat back on my heels, studying the bed carefully. There was no sign of a struggle, nothing overturned. No hint on the aetheric of trauma.

Isabel had not been harmed.

Not here.

That maddening ghost of a trace eluded me. I hadsensed it before, but I couldn’t force the memory to appear. It hovered like a fog at the edges of my awareness, but never came close enough to drag into the light.

My hand remained in the hollow of Isabel’s bed, where her body had slept. I could feel each individual fiber of the cool cotton sheet. I could smell the sweet perfume of her hair on the pillow.

Gone.

Luis had moved to the closet and now was conducting a methodical search of the room, calling Isabel’s name in a calm, loud tone that grew gradually louder, gradually less calm as each hiding place was eliminated.

His hands were shaking. Not just trembling, but shaking, like a man gripped by extreme cold.

After he’d looked beneath the bed, he looked across it at me, and I said, “She’s not here, Luis.”

His face flushed red, then pale. “She’s here. She’s hiding, that’s all. ISABEL!” He bellowed it this time, got to his feet, and charged out of the room. I heard the sound of his footsteps, his calls, the sounds of doors being opened and shut. Sylvia’s strident demands to know what he was doing. Veronica’s softer protests.

The screams when Luis finally told them the child was gone.

I stayed there motionless and silent, staring at the dirty rag doll. It was the one the child had been holding the first time I’d seen her in her front yard. One black button eye was missing, and a seam beneath the right arm had given way. Discolored, soft stuffing poked through.

She’s gone.

Someone had taken her. It hadn’t been the Norteños; I had their scent now, I knew they wouldn’t have bothered to abduct a child unless they expected money or blood in response. Lolly had not acted like a man who’d given such orders, though he might have, if pushed. He’d not gone so far, not yet.

Someone else had. Someone with roots in power. A Warden. A Djinn. Someone I had likely touched, possibly even trusted.

They had just made a terrible, terrible mistake in their choice of victims. I had killed for Manny and Angela in a fit of rage and shock. I would do it with cold, measured violence this time, to regain the child.

Outside the room, Sylvia was calling the police. I heard Luis slide down the wall, beaten down this time by his grief, but his grief was different from mine. Mine was a cold, alien thing.

I stood up and retreated to the hallway, where he sat like a broken doll. I crouched down to look into his eyes.

“She’s gone,” I said, “but I think I know what path we have to follow.”

“The Norteños—”

“No. They might have shot into the house, but they’re not so stupid as to invite a child-abduction investigation. They would be destroyed by it.”

His hands were still violently trembling. “Some predator, then. Some bastard predator.”

“No,” I said slowly. “I don’t think so. I think it had to do with us.”

“Us.” The flat panic in Luis’s eyes receded. “What do you mean, to do with us?”

“Someone wants us stopped; we have ample evidence of that. Together and separately, we’ve been marked. How better to stop us than to take the child, knowing we both care for her safety?” I willed him to understand me. When I was not certain he did, I reached out and gripped his cold hands in both of mine. “ Luis.There is a trace of power in that room. Warden or Djinn, I can’t tell, but we mustfind out. Question the one who was supposed to watch over her. Either they were bought off or disabled. We need to know what happened.”

His fingers twisted and gripped my wrists, hard.

He pushed me away. I rocked backward, but it’s not so easy to overbalance a Djinn, even so little as I now was. My grace seemed to anger him even more.

“This is your fault.” He almost spat it in my face. “It started with you, you coming here and making trouble. If anything happens to Isabel—”

“If anything happens to Isabel,” I said, “I will take my payment in blood and screams. And then you may take yours, from me. I won’t fight you. I’ve done enough harm here already.”

Because he was right, of course. This had all started with my arrival. Whatever I had done to trigger these events, trigger them I had; I owed Luis Rocha a debt I could never pay, even before the abduction of his niece.

Someone, somewhere had struck at me, and shattered the lives of everyone standing near me.

That, I could not forgive.

As a Djinn, I could neverforgive.

Luis was unable to raise the Ma’at who was supposed to be watching Isabel. I couldn’t find him on the aetheric.

It was a very bad sign. “He wasn’t bought off,” Luis said. “Not Jim. No way in hell. He was a friend, and a good one.”

He was likely dead, then. Our enemies had assassinated him quietly, without attracting anyone’s attention, and then come for the girl. It had been well planned and executed.

It made me wonder why they had not done the same for us.

The police arrived. They were not the same as the ones who’d been involved in Manny and Angela’s shooting, but they made the natural connections—Luis’s former gang affiliation, the deaths of Isabel’s two parents. Luis was taken away for questioning, although both Sylvia and I insisted he had never been out of our sight long enough to accomplish the abduction of the child.

With the arrival of detectives—a higher order of policemen, I realized, like the difference between Djinn and Oracles—the questions took a personal turn. Luis had arranged to have me cleared of blame in Scott Sands’s disappearance, but this was three times in only a few days that I had been standing at the center of a criminal investigation.

I supposed it was natural for them to find this odd, but the feeling grew within me that we were wasting precious time while the police collected their painstaking samples, took photographs, questioned suspects, and conducted a spiral search of the house, the yard, the neighborhood.

“Look, it’s still possible the girl could have run away,” one of the detectives said to me as I stood on the porch outside, under the glare of portable lights. Yellow tape flapped all around the house. There were news vans now parked at both ends of the street, held back only by the barricades, and Sylvia’s neighbors had turned out in force to murmur and gawk. “Did she seem upset?”

“Of course,” I replied. “Her parents were killed. But I don’t think she’s run away.”

The detective quirked one perfectly shaped eyebrow. She was a small blonde with a tendency to smirk that irritated me beyond bearing. “Why not?”

“Because she left her suitcase,” I said. I had seen it sitting in the corner of the room, covered with pink flowers and Barbie doll stickers. “And she left her doll.”

I had succeeded in wiping away her smile. “I see.”

“It’s possible, if she decided to run away, that she would go home,” I said. “But for such a small child, it’s too long a walk, even if she knew the way.” There {he aw were many dangers in the world, predators ready to snatch up the unprotected. I felt sickened by the prospects, but I knew in my heart—what a human feeling—that Ibby had not gone.She had been taken away.

I had a strong and growing conviction that the police, well-intentioned as they were, could not help us in this, and the longer we stayed here, trying to fit in, the worse things would become. Like the investigators, I knew that trails rapidly went cold, especially such slender trails as I had to follow.

It would be very inconvenient to be jailed as a suspect.

“You don’t seem too upset,” the detective said to me.

I cocked my head slightly as I thought it over, as I’d often seen humans do. “I don’t? I suppose I’m in shock.”

“No. Your friend Luis, he’s in shock. Grandma Sylvia’s in shock. You’re not in shock.”

“That makes me seem suspicious, I suppose.”

“You think?” She smiled again, and it raised alarms all along my spine. “We’ll continue this discussion downtown.”

She took my arm. Across the yard, I saw Luis, cornered by another detective, notice what was going on. I didn’t know what to do—cooperation seemed a waste of time, and violence counterproductive—but Luis reached out, put his hand on the detective’s shoulder, and gave him a wide, warm smile. Then he shook hands with the man and came toward me.

“You can’t talk to her now, sir,” my detective said. Her tone wasn’t inviting any arguments, and her grip on my arm was just as firm. “Please go be with your family.”

“She is family,” Luis said. The detective gave him a look that was so full of incredulity that even I smiled. “Distant relative.”

“Yeah? What galaxy?” The detective tugged on my arm again. “Come on, ma’am. Let’s go.”

“Detective. One moment.” Luis was still smiling, warm and wide, and he captured her flat stare with his. “Thank you for all that you’re doing to help us.” He extended his hand. I knew what he was doing—it was an Earth Warden trick, one of making themselves seem likable and trustworthy—but I could see that it wouldn’t work on this woman. She had a streak of distrust as dark as rust through her brittle, bitter aura.

“My job,” she said shortly, and added her other hand to push my shoulder. “Move it.”

I glanced down at her feet, and whispered into the ground. I was learning, from the carefully controlled way that Luis applied his skills, that for an Earth Warden subtlety was as effective as brute force.

Green grass looped up in ropy strands, lashing her ankles, burying her sensible shoes. When she tried to take a step, she overbalanced, and for a moment she clung closely to me before she let go to crouch down to see what was holding her. “What the hell—?”