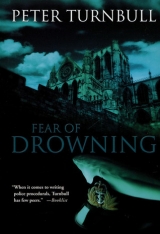

Текст книги "Fear of Drowning"

Автор книги: Peter Turnbull

Жанры:

Триллеры

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 8 (всего у книги 11 страниц)

‘He is, or was, or whatever.’

‘Well, our first impression was that he was a brother of restricted growth, all the doors in the house had handles set low down, at about waist level to the average person.’

‘That doesn’t mean anything.’ Yellich turned to Pastor Cyrus. ‘That was the Victorian fashion, it just made sense to have door handles which were at hand height if the adult was standing with his arms by his side. It was only in the twentieth-century that we thought it would be a good idea to put door handles at shoulder height.’

‘Oh…but even so, there were, and still are, other indications: the sink in the kitchen, well, one of them, was lowered, there was also a small cooker very low on the ground and some wooden steps by the bath and a sort of platform in the bath on which to sit or stand. We have retained them because we find it useful for the children.’

‘I’d be particularly interested to see the bathroom.’

‘The bathroom with the steps and the platform? I ask because we have three bathrooms.’

‘Yes, that one.’

Yellich and Pastor Cyrus approached the steps of the house and as they did so the large door with a highly polished brass handle swung open silently. A girl of about eighteen years, full white robe and sandals, hands crossed in front of her at waist height, stood in the doorway.

‘This is Lamb,’ said Pastor Cyrus.

Yellich smiled at Lamb, who said nothing but cast down her eyes in a gesture of humility.

‘Lamb,’ Pastor Cyrus addressed the girl, ‘please escort our brother to the children’s bathroom and also anywhere else he wishes to go.’ Then he turned to Yellich. ‘Lamb is a recent convert, she has been with us for only a month now and so is still a novice. Please don’t ask her questions because she has taken a vow of silence which she must keep for three months, except for one hour each evening when she may ask questions of the elders as part of her training. Apart from that she may not utter at all except in an emergency.’

‘So she can yell her head off if the house catches fire?’

But Pastor Cyrus simply smiled and said, ‘If you’d like to follow Lamb.’

Lamb took Yellich into the cool, dark, spacious interior of the old house. In the front hall men and women, all in robes, read in silence. Lamb climbed an angled staircase and walked along a narrow corridor. In one room off the corridor, Yellich saw rows of children sitting in front of computers with determined concentration. Not one looked up as he passed the open door of their room. Presently Lamb came to the bathroom in question, stood on one side of the door, bowed her head and with a fluid wrist action, bade him enter the room.

So this, Yellich thought, as he entered the room, was where Marcus Williams died. It was a rectangular room with a deep, long bath set in the middle of the floor, as was often the style in Victorian houses – it was a bathroom, so let the bath dominate it. A shower attachment, obviously of much later design, was fastened to a stainless-steel support, very barrack-room basic.

It would not have lasted long if the house had had a woman to organize it, but it would, thought Yellich, suit the functional, no-frills needs of a bachelor. He noted the wooden steps leading up to the bath which were not attached but could be set apart if necessary, and a seat or a platform in the bath which was of wood and suspended from the sides. It was about three feet wide, and so, thought Yellich, more probably a platform for a person taking a shower, than an infirm person sitting on it rather than fully in the bath. Yellich turned to Lamb and said, ‘Thank you. I’ve seen enough.’

Outside, Pastor Cyrus stood motionless in the sun, awaiting his return. Yellich stepped out of the cool of the building and into the heat.

‘Computers?’ he said.

‘This is not an archaic church, brother Yellich. God wants us to keep up with His times.’

‘I liked him.’

Sam Sprie sat in an upright chair outside the front door of his small council house. Yellich sat beside him in a white plastic chair which had been brought from the rear garden for him. They sipped tea which had been pressed on them by an insistent Mrs Sprie who had then departed dutifully into the shade of her home, behind a multicoloured fly screen in the form of many thin strips of plastic which hung on the door of the house, not a permanent fixture, but put up and taken down as the need arose. The garden in front of Sam Sprie’s house was a sea of multicoloured flowers, mainly pansies, boarded by a small privet hedge, neatly trimmed, green at either side, yellow at the front. It was a gardener’s garden. ‘I hardly ever saw him.’

‘You hardly ever saw him, yet you liked him?’

‘That’s why I liked him. He allowed me to get on with my job and didn’t interfere, you can always tell whether your gardener’s working. So long as I shut the gates behind me, as Mrs O’Shea had to as well. We both had a key to the padlock on the front gate so we could let ourselves in in the morning and lock up behind us after we left for the day.’

‘So there was just Mr Williams in the house each evening?’

‘Each evening and each weekend. Mrs O’Shea and myself worked five days a week. Mr Williams could cook a meal if he had to, so he didn’t starve when Mrs O’Shea was ill, or on holiday, or each weekend. But no, he wasn’t alone strictly speaking, he had three Dobermans. He was safe, all right, the Dobermans knew me and Mrs O’Shea and Mr Williams but practically nobody else. The post was left in a box by the gate, as was the milk. The Dobermans would protect him, at least buy him enough time to phone the police.’

‘And how would the police get through the gate and past the dogs?’

Sprie smiled and nodded his head. ‘Don’t think he thought of that. He was a bit like those people who barricade their homes against burglars, which is all very well until you want to get out to escape the fire. Bars keep them out, but they also keep you in. But that was Mr Williams. A little…what’s the word?’

‘Eccentric?’

‘Aye, that as well.’

‘What sort of man was he?’

‘Better ask Mrs O’Shea that, she knew him better than I did. Like I said, if the garden was kept he never bothered me. I never saw him, save in passing, never went into Oakfield House.’

‘He drowned in the bath?’

‘You asking me or telling me?’

‘Asking.’

‘Aye…well, there’s some as says he did and some as says he didn’t.’

‘Meaning?’

‘Well, his death just didn’t seem right…he never took baths but I didn’t know that until after he died. Mrs O’Shea…she’ll…’

‘Aye…I’ll ask her.

‘He lived alone. A recluse?’

‘That’s the word. I’ve been thinking of him as a hermit but the word didn’t fit…recluse…yes, I like that word.’

‘No visitors at all?’

‘One or two over the years, a tall man would visit once in a while. I was told that was Mr Williams’s brother…first time I saw him he drove up in a car with a wife and a couple of children…I was close by that time…he went into the house looking worried, made the children and his wife wait in the car a good long while. Then came out looking pleased with himself, I saw him smile at his wife and tap his wallet…you know, his jacket breast pocket. His wife smiled back. Then they drove off.’

‘What do you think had happened?’

‘He tapped him for some money. That’s what I felt. Since then I’ve only ever had the impression of the brother visiting Mr Williams whenever he wanted money. Nothing regular about the visits…I mean, I’ve got one surviving brother and we see each other at the Sun each Sunday lunchtime. It was nothing like that. Mr Williams’s brother would visit as and when and stay for about half an hour then he’d not visit again for three, four months, then he’d turn up and leave again as though he’d got what he wanted. Didn’t take to him. Mrs O’Shea told me that Mr Williams was upset that his brother had kept his wife and children in the car when they visited that first time, he felt as if his brother was ashamed of him.’

‘Ashamed?’

‘Well, Mr Williams, he was about that high.’ Sam Sprie held a sinewy arm out level about three feet from the concrete path on which he and Yellich’s chairs stood.

‘Was he self-conscious about it?’

‘Well, if he was, his brother hiding him from his sister-in law and nephew and niece didn’t help, especially when the only reason they visited was to tap him for cash.’

‘It wouldn’t. I’m surprised he entertained his brother at all.’

‘He was a generous sort. He had a lake in the grounds.’

‘A lake?’

‘Very big pond, very small lake…it was circular, about from here to that tree from bank to bank.’ Sprie pointed to a magnificent oak tree in a field opposite the line of council houses. Yellich thought the distance between house and tree to be about two hundred yards.

‘Big enough.’

‘It was about ten feet deep with steep sides, it was excavated by the man who had Oakfield House built back in the eighteen-thirties. He created the lake and had it stocked with trout. Anyway, the lake hadn’t been fished for a while before Mr Williams moved in and when he moved in it was just teeming with fish. We were looking over the grounds after he’d taken me on and he told me he wanted the lake filled in. I asked him if we could take the fish, we have an angling club in the village…he said yes…we organized ourselves, no more than six rods at any one time, each man having a four-hour slot…and still it took us a week to fish out the lake. He was generous like that, but that week sticks in my mind because there were more folk in the grounds than ever before or since, and in that week I never saw Mr Williams once. But he was accepted well after that, people knew about him, and left him alone…not like the group of weirdos that are in there now…we don’t know what’s going in the house, aye.’

‘Any other visitors that you recall?’

‘Only one, a young man, called a few times…this was in the last year of Mr Williams’s life…a friend, a relative…I got the impression that he was calling on Mr Williams, not his money…he also liked the dogs and they took to him after a while…throwing sticks for them. He was seen in the village at about the time Mr Williams died. Not by me, by Sydney Tamm. He used to be the church warden at St Mark’s.’

‘Used to be?’

‘He’s still alive…’

‘Where do I find him?’

‘Ask at the vicarage. That’s St Mark’s.’ Sprie pointed to a steeple, dark grey against the blue sky. ‘The vicarage is behind the church. The vicar will put you right.’

‘I used to enjoy doing for Mr Williams.’ Tessie O’Shea sat in an armchair with a black cat on her lap. ‘Just me and Petal now, isn’t it, Petal? You know, you get to an age when all you can do is enjoy each day for its own sake and not worry too much about the future.’ Tessie O’Shea’s cottage was small and cosy and warm and homely. As much as Sam Sprie’s garden had been a gardener’s garden, Yellich thought that Tessie O’Shea’s cottage was a domestic worker’s domicile.

It was a stone-built structure with thick stone walls which Yellich knew would be warm in the winter when the open hearth was burning and he noted it to be cool in the summer.

The stonework above the door of the cottage had a date—1676 AD—carved into it and it sobered Yellich to ponder that when Napoleon retreated from Moscow Mrs O’Shea’s cottage was already in excess of two hundred and thirty years old. ‘But you want to know about Mr Williams?’

‘Yes. Huge house for you to look after.’

‘If he lived in all of it, it would have been, but he had the one bedroom, the one sitting room, the one study, he ate in the kitchen. The rest of the house gathered dust. So I could manage it. You know when I said he used to eat in the kitchen, I meant that he sat down with me and ate at the kitchen table, me and him ate together, him in his high chair…what kind of man would sit down and eat with his domestic? A gentleman would, that’s who would. He was a gentleman, treated me as an equal. I loved working for him. I did better for him because of it…his attitude, I mean. I always made sure he had plenty of tinned food in so he could survive if I wasn’t there, so he didn’t have to go out to the shops. He was a bit shy about his height, he was a small man, about three feet high. It wasn’t so bad when I was ill for a day or two, or at the weekends, but I used to enjoy a fortnight in Ramsgate every July. I’d worry about him then.’

‘I understand that it was yourself who found his body?’

‘Aye…me…I’ll never forget it…I knew something was wrong…the dogs, you see, they were in a strange state…looking sorrowful…whimpering…and they flocked round me when I rode up on my bicycle…as if I was a rescuer. I went into the house…the dogs had licked their water and food bowls dry…so I gave them some water, plenty of water…it was the summertime, this time of year…and then went looking for Mr Williams…calling out his name…found him in the bath…his little body and all that water. Face down, he was. There’s a few things that didn’t add up, oh no, they didn’t, didn’t add up at all.’

‘Such as?’

‘Well, for one thing he didn’t take baths. He had a fear of drowning, he had the lake in the grounds filled in for that reason, pretty well the first thing he did was to fill in the lake.’

‘Sam Sprie has just told me, he let the angling club fish it out, and then filled it in.’

‘Yes…that’s right…the village liked him after that…but those people that have got the house now…but anyway, he always took showers, had a platform built to stand on…he had the shower put up for him, bit of a contraption but it worked. Then he had some steps built up to get from the floor onto the platform. The bath was a bit big for him to get into…you imagine a bath ‘Yes.’

‘The rim of which is just below shoulder height as you stand against it, if you’re in it and outstretch your arms, you can touch either side, just, and if you stand at the opposite end of the bath to the taps, it takes you half a dozen full-length strides, at least, to reach the taps…well, that was the size of the bath for Mr Williams. I can see why he was frightened of drowning.’

‘So can I, since you put it like that.’

‘And when I found him, the steps and the platform were up against the wall, well away from the bath…he couldn’t have got into the bath without the steps.’

‘Are you suggesting someone else was involved?’

‘I’m not suggesting anything, but…well, this is going back ten years now…but the bath was filled with tap water.’

Yellich raised his eyebrows as if to say, What other sort of water is there?

‘I mean,’ said Mrs O’Shea. ‘I mean as opposed to water from the shower. The taps on the bath were never used, they hadn’t been used at all during the time that Mr Williams was the owner. The house was empty for a while before Mr Williams moved in…they’d rusted shut…I couldn’t turn them on, I used the water from the shower when I cleaned the bath. I don’t say they were rusted solid, a strong man could have turned them on, but I couldn’t, and Mr Williams didn’t. But when I found him, the shower was dry, not dripping, because Mr Williams never turned it off properly, but the taps were dripping. And I turned them on and then off again, easily, they’d been freed off.’

‘Hence the open verdict,’ Yellich said more to himself than Mrs O’Shea.

‘Probably. There was something deliberate about the death, but I don’t think anybody wanted to say suicide…no note or anything…Mr Williams wasn’t depressed…he was just trotting along with life and had a good sense of humour…I mean, he didn’t like being a cretin, he told me once that that was his medical condition…I’ve heard the word being used as an insult, I never knew it was a real medical condition until I met Mr Williams, but he just accepted it…his dogs didn’t see him as a dwarf. The gardener never saw him from one week to the next, he had few visitors…there was just me…and after a while, after a short while, I didn’t see him as different at all. I got to like doing for him, as I said. Used to talk to me, tell me how he’d done on the stock market…“Did well today, Mrs O’Shea,” he’d say or, “Didn’t do too well, but I’ll make it up tomorrow.” Then he’d spend time with his dogs. He loved them and they loved him…didn’t take them walks but they had the run of the grounds. He just wasn’t a suicide type person. There was nothing to do with the dogs after he died but have them put down. They pined for him…they wouldn’t be taken from the house…I know what they felt…I gave up my work after that and settled for my pension and my savings. I just couldn’t do for anybody after Mr Williams.’

‘Did you ever meet his relatives?’

‘His brother once or twice, Mr Max Williams, smooth type, gold fillings…all smiles and daggers…he visited once and left his wife and children in the car outside the house on a hot day…after that he just visited alone. One day…well, see, if you “do” for a man or a family long enough you get to know what’s going on and once Mr Williams told me that his brother was getting expensive, then he said, “but what can I do? Blood is blood.” That’s what he said. “Blood is blood.”’

‘Did you meet his nephew or niece?’

‘The nephew. The navy man. Arrogant giant of a man. The way he looked at me…like dirt. He called me “O’Shea” and he called the gardener “Sprie”, just surnames…but never in Mr Williams’s hearing. He was handsome in his uniform and he knew it, very full of himself. I suppose the girls would go for him. Visited Mr Williams a few times in the last eighteen months…spent time with the dogs…bought them licorice…dogs are fond of licorice…walking the grounds with them. They got to wagging their tails when he came.’

‘One last question, Mrs O’Shea, the day you found Mr Williams’s body. What day of the week was it, can you recall?’

‘It was a Monday. Definitely a Monday. It’ll be written up, you’ll be able to check it, but I can tell you it was a Monday. First day of the week, last day of my working life.’

Yellich walked the short, but not unpleasant, walk to the vicarage which was not, to his surprise, a stone-built, ivy covered house, but a newly built semi-detached house set in a neat garden and a gravel drive. He thought himself fortunate to find the Reverend Eaves at home. He revealed himself to be a tall, kindly seeming, silver-haired man and was pleased to direct Yellich to the home of Sydney Tamm who had been church warden at the time of Marcus Williams’s death.

Sydney Tamm was by contrast a short man with a furrowed brow. He drove the garden fork into the ground between the row of potato plants in his front garden and looked at Yellich.

‘Police?’

‘Aye.’

‘About?’

‘Marcus Williams.’

‘Aye. Sitting up and taking notice at last, are you?’

‘Should we?’

‘Aye. Mind, I can’t tell you anything that’s not known, isn’t known…well, you’d better come into the house.’

The closest description that Yellich could find for Sydney Tamm’s house was ‘refuse tip’. It even smelled like one. The accumulated tabloids revealed that it probably hadn’t been cleaned for the last five years. The house was probably difficult to live in in the winter but the summer heat made the smell near unbearable to Yellich. Many flies buzzed in the window or flew in figure-of-eight patterns in the air above the table on which remnants of food remained on dirty plates, themselves on newspaper which served as a tablecloth.

‘I’m not proud of my house. I’m not ashamed of it.’ Tamm sat in an armchair. ‘You can sit in that chair there, if you want, but most of my visitors choose to stand.’

‘I’ll stand.’

‘Suit yourself.’ Tamm reached for a packet of cigarettes, and taking one, lit it with a match, putting the spent match back in the box. ‘She’d turn in her grave if she could see her house.’ He nodded to a photograph of a bonny-looking woman which stood, in a frame, on the mantelpiece.

‘You were the church warden of St Mark’s?’

‘Was. Don’t qualify…not a Christian any more, am I? Can you imagine a Christian living in a house like this? Cleanliness is next to godliness. I had religion all my days, and then my Myrtle took cancer…if there was a God, He wouldn’t have let a good woman like her suffer like she did. I buried her decent like, but then I told the vicar I wanted no more of his cant. I spend my days down the Dunn Cow now with the rest of the old lads of the village…it’s the only pub around here for the fogies, all the rest is for the young ’un’s, all that music, them machines with their weird sound and the flashing lights. But the Cow, it’s still as a pub should be.’

‘You don’t use the Sun with the angling club?’

Tamm looked at Yellich, as if surprised at his knowledge of Little Asham. ‘No…no, I don’t use the Sun.’ Said as if there was a story…a fall-out with the publican, a row with the anglers. Something had happened. ‘The Cow’s all right and all those boys who have never had religion have all been right all along, and the vicar and me have been wrong all along. The vicar, he calls from time to time, but less so now, he’s giving up on me…his lost sheep is gone…devoured by the wolf at the Dunn Cow.’

‘I’m sorry.’

‘The smell is terrible.’

‘It’s not so bad, a good clean, plenty of disinfectant, you could get on top of your house again in no time.’

‘Cancer. The smell of cancer. It’s a terrible smell. It’s one of those smells…smell it once and you’ll never forget it…it stays in your nose. Myrtle…she had it on her skin…started out as a mole…then it was all over in the end, all over her. Her skin looked like…poor Myrtle…even now, five years this November, I can still smell the smell. I sleep downstairs, the smell hasn’t left the room where she died. Not properly…I won’t open a window, nor the door.

Do you want to go up and smell it?’

‘No…I don’t think so.’

‘If you did, you’ll never go near those canting priests and their steeple houses again.’

‘Again, all I can say is I’m sorry.’

‘Aye…look, I don’t get my pension for a day or two, I don’t suppose you could let me have the money for a beer, only there’s a darts match at the Cow?’

Yellich took his wallet out and laid a ten-pound note on the sideboard. ‘Tenner OK?’

‘Thanks…I can go out tonight.’

‘So, Mr Williams?’

‘Aye, there’s still rumours about yon. I saw a young man driving through the village on the day he died, the Sunday. I’d locked up the church after Evensong, that would be at seven-thirty. I was walking home when the car passed me, going quite fast for the narrow road. Saw the driver, young man…’

‘He was driving away from Oakfield House?’

‘Yes. He came to the village and took the York road. It goes through Malton, but if he was going to the coast, there’s another road he’d take which would avoid Malton. It’s a fair bet he was heading to York, in that direction, anyway. I didn’t recognize him, he was a stranger. But I saw him just once again…he was a mourner at Mr Williams’s funeral; being a church warden, I was at the funeral…making sure everything was where it ought to be, and he was there, same young man, then he was in a naval officer’s uniform.’

Yellich returned to Malton, and parking his car in front of the police station, ensuring that the ‘police’ sign was in the windscreen, he set off on foot, seeking the firm of Ibbotson, Utley and Swales. He amused himself by looking for it, rather than enquiring as to its location. Exercising logic, and the benefit of previous observation, he confined his search to the older part of Malton where he found one solicitors’ office, then another, then an estate agent’s, then beyond that, the building occupied by the firm of Ibbotson, Utley and Swales.

‘Our juniors never let up, not allowed to.’ Julian Ibbotson reclined in his chair in an oak-panelled room which reminded Yellich of Ffoulkes’s office in the Yorkshire and Lancashire Bank in York, the same solid, timeless quality. ‘Every ten minutes has to be accounted for. Not like that when I started, I doubt I could stand the pace. I belong to a different era, thank goodness. Too fast-paced for me, even in sleepy Malton. Retirement beckons, oh my, how it beckons.’

‘You have plans for your retirement, sir?’

‘Oh yes…plans, plans and yet more plans. But enough, I understand that you wish to see me about a client of ours?’

‘Ex-client. Marcus Williams.’

‘Oh yes…Oakfield House, open verdict…eight, ten years ago?’

‘That’s the one.’

‘If you want to access the documents you’ll need a warrant, but I wish to help and so I’ll answer any questions as accurately as I can.’

‘Why do you wish to help?’

‘The open verdict. I’m a lawyer, you are a police officer, we both know what an open verdict means.’ Ibbotson smiled, a thin smile from a long face.

‘A piece of the puzzle is missing?’

‘Yes…his death was no accident, he wasn’t the suicidal type…he had a physical condition which may, nay, certainly would have taken some coming to terms with, but once he’d made the adjustment he had a lot to live for. Foul play cannot be ruled out.’

‘It can’t?’

‘And a police officer from York, not our local branch of the North Yorkshire Constabulary, what, I ask myself is this to do with the double murder of Mr and Mrs Williams of which I read all agog in the Yorkshire Post a day or two ago?’

‘Much,’ said Yellich. ‘Possibly. We are pursuing a line of enquiry, more than one, in fact. Can I ask you who benefited from Mr Marcus Williams’s estate?’

‘His brother. The now also deceased Mr Max Williams.’

‘Quite a sum was involved?’

‘About six million pounds. And that was after death duties. Later he came into another half-million pounds when Oakfield House was sold to those who have come to save us. They and their oxen.’

‘Yes…’

‘Confess I’m more than a little surprised that Mr Max Williams should be living in such a modest bungalow when he died. I saw the photograph in the Post and I nearly fell off my chair. Can you tell me if it was by choice or necessity that he lived in such a small house?’

‘Necessity.’

‘That takes skill.’ Ibbotson fixed Yellich with steely eyes.

‘Getting rid of six million pounds in ten years is an act of consummate skill.’

‘Any other beneficiaries?’

‘Scanner appeal at the hospital in York, plus a charity for disabled persons, quite generous, I suppose, in comparison to the usual donations they receive,, but neither sum made a dent in his estate.’

‘What about his niece and nephew?’

‘I didn’t know he had a niece and nephew and thereby I answer your question. All went to his brother, save a hundred thousand to the scanner appeal and a similar amount to the disabled persons charity.’

As he drove back to York, Louise D’Acre entered Yellich’s mind. He had always seen the Home Office pathologist as being headmistressy in a prim and stuffy sort of way, driving the old Riley as if fashion and modernity didn’t reach her, yet all the time she had been cherishing her father’s memory by nurturing his one and only motor car so that it still gave sterling service long after its design life had expired.

Frightening, he thought, frightening how you can be wrong about people.