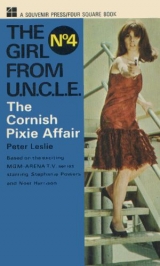

Текст книги "[The Girl From UNCLE 04] - The Cornish Pixie Affair"

Автор книги: Peter Leslie

Жанры:

Боевики

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 8 (всего у книги 10 страниц)

She reached into the handbag again and drew out what looked like an ordinary hairpin. The light was fast fading, but she would have to do what she could... Twisting the special wire into a convoluted shape, she inserted it into the keyhole of the padlock and attempted a turn. It would not move.

She withdrew it and made a minute adjustment to one end. This time, it began to turn and then apparently fouled on some thing inside. For the second time she took it away and effected an alteration. It turned further but still would not go the whole way. On the third attempt, the wire she was manipulating bent slackly at a corner and then parted, so she had to begin all over again. But with the new piece, she was lucky first time: there was a firm click and the padlock tongue sprang open.

With a gasp of relief, April turned to the lighter again. Now that she had two hands, the task would be that much simpler – especially as she no longer had that agonisingly cramped posture imposed on her. It was, however, going to be no easy job: in the first place, she would be unable to look directly at the fierce flame, so that accuracy would be a hit-and-miss matter. There were specially tinted glasses for use with the blowtorch lighter, but she did not have them with her. Secondly, the combustible by-products of the oxy-acetylene flame made a pungent and instantly recognisable smell... and she had no idea how far away she was from the main part of the house where Wright and his henchmen had no doubt gathered with the mysterious Colonel Forsett – whoever he was.

Thirdly, the flame – even a tiny one like this – was noisy. And lastly, she had no idea if it would last long enough to cut through the chain.

Feverishly, she took the links between her two hands. It must be cut as near to her foot as possible, for with a clanking length of chain fixed to her ankle, she would be a sitting target. On the other hand, since she could not for long look at what she was doing, there was a very real risk that she would sear through her boot and injure her leg. Eventually she decided on the third link out from the anklet and thumbed the mechanism of the lighter.

A thin tongue of flame shot ten inches into the air with a muted roar. Setting the torch on the floor, she twisted a couple of tiny handkerchiefs around the two links between the area of operations and her boot to insulate them from each other and try to minimise the heat transference. Then, picking up the lighter, she directed the flame at the third link.

In an instant, it seemed to her, the cellar became an inferno of odours and noise. The hiss of the pressurised flame and the rattle of the chain on the stone flags warred for attention in her over-sensitive mind with the acrid, throat-catching tang of the gas, the flat, sour smell of heating metal, and the stench of charred handkerchief and varnished leather.

Averting her eyes from the fierce incandescence which lay at the centre of the shower of sparks, she held the torch grimly in place. The centre of the link was cherry red when she turned off the flame and paused to listen.

In the sudden silence, the assorted smells of the operation seemed stronger than ever. Far away, a motor car engine started, revved up, and then died away into silence. Otherwise there was no sound. Colonel Forsett and his wife, she imagined with an inward smile, had either just arrived or just left. Or perhaps Wright's wife had returned. Or Wright himself had gone. In any case, it was perhaps a good thing, for whichever of those alternatives was true, it was likely that its result would be momentarily to focus attention away from her.

Pumping at the handle, she returned to her task.

Several times, the intense heat transmitted by the links forced her to snatch her foot away; once the agony of looking too closely at the flame caused her to waste a half minute of flame on the stone floor. But finally there was an appreciable opening in the curved iron of the link.

And then the flame dwindled, guttered, and died out.

Desperately, April pumped and pumped; furiously she clicked at the mechanism – but there was no response. The little tank was exhausted.

The girl was almost crying with exasperation. So very near, and yet...She set her teeth and waited for the hot metal to cool. Once it was brittle again, there was a faint chance that she could utilise the gap she had made to force the link apart. Planting her shackled foot at the full stretch of the chain away from the wall, she placed the other at the height of the ring, flexed her knee and began to push.

There was a tiny metallic chink! and she was suddenly pitching over backwards, to land with a jar against the opposite wall. But she was free!

Panting, she leaned against the cold granite and listened. No sound interrupted the laboured breathing exuding from her own lungs. Picking up her handbag, she dropped the lighter inside, twisted the opened padlock out of her wrist iron, and walked across to the window. There was a light metallic tapping from the two links of chain still attached to her anklet, but it was not too bad.

The window opened on an ordinary latch. She swung it outwards, hauled herself up, and climbed into a narrow area.

It was quite dark now, and the wind was moaning softly among the tops of the tall trees which sheltered the house. In the flagged yard above the area, now that she could see all of it, a Humber shooting brake stood outside the barn whose roof she had been looking at from inside her cell. Beyond, light streamed from an open doorway leading into an immense garage, winking from the sophisticated curves delineating the body of a D.S.21 Citroen. The main part of the house bulked against the sky behind her – and she imagined from the suffused radiance outlining the roof that the lighted windows were all on the far side.

For a moment, she toyed with the idea of trying to steal one of the cars – then prudence overrode imagination: Wright had spoken of special devices to stop people trying to escape, and they would be on to her as soon as she pressed the starter. No, the stealthy exit to the cliffs, followed by a run down to Porthallow and a return in force with Mark – that was what was needed now.

In the instant that the thought was formed – and before she had had time to look around and take notice of the lay of the land – a man in chauffeur's uniform walked out of the garage and saw her. His exclamation of surprise was echoed by an angry shout of alarm from the cellar from which she had just escaped.

In a flash, April turned and ran, away from the light, away from the cellar, away from the chauffeur who was tugging a gun from his waistband. Before she had gone three steps, light shafted into the darkness from the cell window, where Wright was climbing out with a torch in his hand.

A shot crashed out behind her and something whizzed into the dark above her head. Water, she thought frantically, I must have water... There was something dripping near the cellar, she remembered: it must have been a tap or a water butt. She clattered to a halt and looked around – yes, there it was! Just behind her. A main risertap with a bucket hooked over it by the handle, against the wall of the house.

"Don't shoot!" she cried. "I give up; I'm coming…"

Slowly, she walked back towards Wright. Beyond him, the chauffeur stood with his pistol cocked, full of suspicion.

"Put up your hands," Wright called. "Walk slowly towards the barn."

In her right hand, April was prising what looked like a life saver from the roll of mints which had been in her bag... but it was a disc that would have frightened the life out of anyone who tried to eat it! As she lifted her arms, she flipped the pellet neatly into the bucket of water and hurled herself to the ground.

The instant that the life-saver touched the surface, a vast outpouring of dense smoke surged from the bucket, rolled across the yard and blotted Wright, the chauffeur, the cars and the garage from sight.

Shots from two different guns thundered as the girl scrambled to her feet and began wildly running away from the life-saving screen. Wright was bawling something in the dark, a bell had begun ringing, ringing, and in the distance she could hear a woman's voice calling. She hurled herself through an arched doorway in a wall, ran along a brick path and blundered into a shrubbery. She knew she only had a moment before they rounded the house the other way to cut her off.

On the far side of the bushes, she found herself on a lawn. The front of the house, mullioned windows ablaze with light, was off to her right. And away beyond, the night sky was speckled with a rash of red lights warning low-flying aircraft away from the masts of Trewinnock Tor.

She realized she was running in the wrong direction, away from the town.

On an impulse, she dropped to her hands and knees and began crawling back the way she had come, behind a line of standard roses.

A moment later three figures ran round the corner of the house and fanned out across the lawn. "Gerry," a woman called, "I should go towards the South Gate if I were you: she may have a car in the lane."

"Good idea!" Wright's mannered voice replied. "I'll go that way. Mason – you head for the boathouse and cut her off if she goes that way."

"Very good, sir," the man in chauffeur's uniform called back.

Grinning, April rose to her feet at the end of the row and walked softly back through the archway into the yard. Most of the smoke screen had blown away, but there were still layers of it wreathing in the light from the garage.

She tiptoed across the swathe of brilliance and glanced into the building. The place was deserted. As she began hurrying back down the path she had taken with Wright earlier that afternoon, she could hear the voices of the pursuit growing fainter and fainter in the distance behind her. So far, so good, she thought... But the lord of the manor had said that there were two servants besides himself and his wife on the premises. There was still one unaccounted for. And there was still the possibility of trip wires, electric fences and other forms of man-trap before she was off the property... She would have to go carefully, especially as she was now out of range of the diffuse illumination from the house and it really was very dark. Later, there would be a moon, but just now it was positively Stygian!

The mystery of the second servant did not remain long unsolved. As she rounded a spinney at the entrance to a field she saw below her the stile over which she had entered silhouetted against the pale fury of the sea, giant hands plucked her from the ground as though she had been a baby.

"Ah, now! What have we 'ere?" a deep voice exclaimed. "You'm beant running away without sayin' thank'ee, be en?... Maister'd never hold with that. I think you'd better come over by the house along of me, my pretty one!"

Twisting in the remorseless grip, April saw that the man was gigantic. He must have been fully seven feet high, and he was muscularly built to match. She chopped a karate blow at his neck, twisted again and seized his wrist in a judo grip– but the giant just laughed, hefted her over his shoulder like a roll of bedding, and began striding up the hill towards the house.

All right, the girl thought, if that's the way you want it... Maybe it's better like this!

Her handbag was looped over one wrist by the handles. Under cover of a girlish thrashing about with hands and feet, she manoeuvred yet another article out of it: a small gold lipstick case.

The hypodermic needle shot out at the touch of a catch, and the point was plunged into the vast wrist holding her on the man's shoulder before he had gone another three paces. The barrel was filled with chloral hydrate, and however tough the man was, this particular Mickey Finn would bring him down long before they reached the house.

Her captor grunted with pain, shook his wrist a little, and then clamped the other more firmly still about the small of her back.

April's head bumped five more times against the giant's back as it hung down over his shoulder – and then suddenly he was staggering, mouthing animal cries, lurching into bushes and trees. A moment later he crashed to the ground and lay like a man dead.

The girl rose shakily to her feet, picked up her bag, and retraced her steps. At the stile, she touched the wooden crosspiece with the bag before she dared to put a hand on it – but there was no shower of sparks, no shot from a booby-trap gun, no electrical discharge. Whatever the seaward defences of Sir Gerald Wright's house were, she was through them.

She climbed over and looked down. To one side, a finger of light probed the boathouse where the chauffeur was searching the cove. Below, breakers snarled in the dark – and round the corner lay the lights of Porthallow.

Then she was in the open, scrambling, running, her hair streaming in the wind, stumbling down the slope towards safety.

CHAPTER THIRTEEN: ONCE MORE INTO THE BREACH

APRIL DANCER stopped three times on her way down to Porthallow to try and contact Mark Slate on the Communicator. Each time she drew a blank: the device's bleeping call– sign remained unanswered. She fell twice in the darkness along the rocky path, and ripped her sheepskin coat on a strand of barbed wire while trying to find a short cut from the cliff to the harbour. By the time she regained the circus field at the top of the town, she was breathless, bedraggled, bleeding from half a dozen minor cuts, and covered in burrs from some bush into which she had stumbled on her way.

The nagging worry she felt at Mark's inexplicable silence was resolved as soon as she had negotiated the noisy crowd thronging the sideshows and gained the comparative quiet of her own caravan. There was an envelope propped up on the table beside the bed, sealed, but with no name and no address on it.

The girl ripped open the flap and drew out the single sheet of paper it contained. He must have been in a hurry, she thought; he had written to her in clear! She read:

Having discovered something rather disquieting about the host of your tea party, I have driven up to see whether I can offer you a lift home. If you read this, of course, my journey will not have been really necessary!... In which case I shall merely make my excuses and leave. Dinner at the Crabber at nine?—M.

With an exclamation of dismay, she crumpled the paper involuntarily into a ball and dropped it to the floor. Foolish, quixotic Mark! After all the trouble she had had in escaping from the THRUSH headquarters, he had himself learned the truth – and dashed in impulsively to rescue her... only far from being able to "make his excuses" and leave, he would find a much warmer welcome than he expected, for the inhabitants of the house up on the moors would know all about him and be only too glad to lay their hands on him.

And now, instead of coding a message reporting to Waverly in New York and awaiting instructions, she would have to dash out again, back into the lion's mouth (to keep the circus parlance) and do her best to rescue him!

There was just one small problem: how was she going to do it?

Mark had taken his car, she thought as she picked the locks of her anklet and bracelet and stripped them off. Even if she could hire or borrow another, it would take time – and time was precious. Whatever Wright's mission was, he had said it was due to end this evening. On the other hand, to struggle all the way up the cliff path again would take even longer – and to go to the house by the inland road, climbing the moors and skirting the DEWS station, was unthinkable on foot. Besides which, the landward side of the place was certain to be the one most closely guarded. If only she could think of some way to land herself on the inside of the defences, there might be a chance...

Staring blankly out of the window, her eyes fell on the figure of Ernie Bosustow, tramping past on his way from the trailer to the sideshows.

Perhaps that was the answer – he was only a boy, but he loathed Sir Gerald Wright, he knew the area, and he'd plenty of guts and defiance and determination himself... which were not bad qualities for a sidekick, in the circumstances!

And she had to have a sidekick: courageous and resourceful though she was, April felt the need for the moral support of a second person on this adventure, even if that person was going to be only a passenger. She strode to the door and flung it open. "Ernie!" she called. "Can you come here a minute?"

The boy strolled across. "Hallo, hallo," he said with an impish look up at her. "What happened to you? You look as though you'd been dragged through a hedge backwards!"

"That's just exactly what did happen to me," April said grimly. "I want to get my own back on the people responsible, and I wondered... Look. Can you come in for a moment?"

He nodded, ran across to the steps leading to the caravan door, and swung himself up. "What's on your mind, then?" he asked.

"Ernie, I need help. I can't go into details but... you were right about Sir Gerald Wright. Not only that: he appears to be tied in with the other thing, the secret thing we're investigating – which is probably why he killed your girlfriend... not because she was embarrassing him with his wife but because she knew too much of his affairs. The point is, Sir Gerald and his people have probably captured Mr. Slate. He went up there to the house, not knowing they realised who he was... and I have to get him out. Will you help me?"

"Right about Wright, eh? That's a bit of a right about turn for a lad as everybody suspects of murder, isn't it?" chuckled the youngest Bosustow.

"Oh, Ernie – don't hold the police attitude against Mr. Slate and me," she implored.

"Don't worry: I'll help you all right. If it's to avenge Sheila, like – and especially if it does that toffee-nosed bastard in the eye – I'm on! But what d'you want me to do?"

"If they have Mr. Slate... and I'm afraid they must have by now... then they're holding him in Wright's house, beyond the radar station up on the moor. My problem is to get inside the grounds without crossing the boundaries in any of the usual ways: they have electrified fences and men with guns and so on." The girl stared at the table for a moment, absently stooped down to pick up the crumpled note from Mark, and struck a match which she held to one corner of it. "You know this region well, don't you?" she asked.

Ernie grinned. "Bet your life. I was at school here – though the family originally comes from further north. But the old man's always said Porthallow was his real home: that's why he winters here every year."

"Well, can you think of any way we could get in there undetected?"

"Hire a helicopter from Goonhilly?"

"I could even arrange that, as it happens. But it'd take too long."

"Of course," the boy said slowly, "there's always the Keg-'ole."

"The what?"

"The Keg-Hole. Natural curiosity, they call it. It's kind of a cave where the sea runs into the cliffs below the old coastguard station – but inside the cave it suddenly opens out and there's the sky above you again. From the landward side, it's like a hole in the ground where you can see the sea at the bottom."

"Why is it called the Keg-Hole?"

"From the shape, first of all. And then again, smugglers used to run kegs of brandy ashore from the French boats there. You can tie up inside and heft the stuff up a path cut in the rock, and nobody sees you until you're up on the cliffs beyond. There's a regular rabbit-warren up there!"

"What – smuggling just by a coastguard station?"

"Ah, you got it the wrong way round – the coastguard station was built in that particular spot because it was used for smuggling! Once the preventive men had their look-out there, the smugglers had to find somewhere else."

"Did I understand you to say that you could take a boat in the cave?"

"Hell, yes – you could get a crabber in there on a calm day."

"What about a rough day – a day like today?"

"Too dicey – but you could run in a twelve– or fourteen-footer, easy. We often used to when we were kids."

"You could get one in now, in the dark?"

"Sure you could, if you knew the cliffs."

"Could you, though?" she persisted.

"Me? Well, that's a different matter!... Still an' all – I don't know. Why not, for goodness sake? I could try."

The piece of paper had burned steadily down until it reached the tiny triangle held up between April's finger and thumb. She pursed her lips and blew once sharply to extinguish the flame, then lowered the crisp ash and ground it to fragments in a saucer. "Could you, Ernie?" she said softly. "And would you... to help me?"

"Sure I would. Why not?"

"The weather's not too bad tonight, is it?"

"No, I guess not. Wind's dropped quite a bit, but there's a hell of a sea still running, of course. It won't be easy."

"Where did you say we came up? – if we took the path, I mean?"

"Just below the old coastguard station. You can't see it from the path, you think the cliff falls dead away – but in fact there's this dirty great shelf sticking out thirty or forty feet below, and the Hole's in that."

"But that… but that's... Ernie, that's no good! We want something that takes us into the Wright property! This way, we'd have all that trouble and still find ourselves outside the stile. We might as well walk up the path!"

"Ah – but I said the hole came out on the shelf. O didn't say we do."

"What do you mean?"

"Half way up the Keg, the stairway stops at a platform – and there's a passage from the platform cut into the rock."

"A tunnel! Where does it come out?"

"Practically where you want! There's dozens of branches – one of 'em goes right under the Tor and leads to an underground storeroom slap under the radar station! – we used to play in it when we was kids."

"But, Ernie – why don't we simply walk along the cliffs to this hole and climb down the stairway to the platform, and get in to the tunnels that way?"

The boy smiled. "You don't know the nineteenth-century coastguards," he said. "Efficiency at the expense of imagination. They dynamited the stairs between the platform and the lip. You can only get to the tunnels from the sea."

"But that would surely mean... No matter! It suits us. Let's go!"

Snatching up the handbag, she held open the door for him to leave, and then ran lightly down the steps, slamming it, shut behind her.

Forever in her mind, the next half hour was a kaleidoscope of movement and of colour. There was the push and jostle through the Saturday night crowd, laughing, shouting, screaming, their open-mouth faces lit harshly from the flares of the booths; the sickly warm smell of candyfloss, nutty fumes from the roast chestnut stall – and over all the strident wheeze of a hurdy-gurdy... And then they were away and running down the hill, past the thatched cottages in the lamplight, under the bridge and into the square, now filled with the headlamps of cars backing and filling to find a place because there was a film showing at the mission halt. Beyond the women in winter coats queuing for the doors to open, they were in a huddle of narrow lanes pricked out with lighted windows or the flickering green of family television... and then at last, salty in the nostrils, there was the cold push of the wind on their faces as they came out on to the quayside.

Ernie took her arm and guided her along the Hard, past rows of gunwales straining at ropes creaking to the swell. They edged beyond a stack of crab-pots pungent with tar and rotting bait and trod along a boardwalk leading out, rising and falling with the moored dinghies to which it was tethered, to the middle of the harbour.

At the end of the planking, he jumped down into a bright green boat with a high bow and stern post and threw the tarpaulin from the engine housing amidships. The craft was about fifteen feet long, April judged, and wide in the beam. There was a curved half-deck which ended just forward of the engine housing, and the bulkhead blanking off the fore– part which this covered held wheel, compass and other controls on one side, and a small door leading to the sail locker on the other. The stern half of the boat was open.

"She's a funny old craft," the boy called up to her. "Originally they built her for a miniature whaler – as an experiment, like – but she was too small. Then she hung about for years, just a hulk for kids to play in. Then Harry, my brother Harry, he got this two hundred horsepower diesel cheap – and he put the two together, and there she is."

"No sail?" April asked.

"No – just the engine. She doesn't even have a mast, that I know of. But she's a sprightly old tub, for all that. Do a good eighteen to twenty knots if pushed! And she's real tough. That's why we're using her instead of borrowing one of me mates' more modern craft."

The girl jumped down into the cockpit. There were a couple of thwarts and a narrow bench which ran around the stern. Apart from these and a pair of oars lying along the duckboards, it was empty.

As Ernie bent down and grasped the handle which turned the heavy flywheel, she looked back at the quayside. Masts, rigging and crosstrees tossed against the illumination of the streetlamps lining the Hard. The moon was up, silvering the shallow slate roofs, mellowing the thatch – and if she turned the other way, she could see the agitated water just outside the harbour mouth in its shining path.

It certainly promised to be very rough. Even at its moorings, the boat was lifting and falling sickeningly. And as soon as the engine caught and settled down to the characteristic diesel knock, and the boy shoved them off and into the middle of the port, she realised how small it really was.

The rollers were marching in between the piers at fairly long intervals – she could hear the continuation of them thundering on the beach at one side of the harbour – and it was not until they were well clear of the warning lights on each break water that they really hit the swell. The old boat lifted its blunt nose to the crest of every wave, hung suspended for a moment, and then crashed down into the trough with a thwack that sent the spray flying and jarred April's teeth in her head. And then the boards were pressing the soles of her feet again as they rose like a lift to the next one.

As soon as they drew out from the shelter of the headland, the full fury of the weather seized them. April was looking out over the stern at the lights of Porthallow, clustered like fruit along the dark branch of the valley, when suddenly they slid away and out of sight and the whaler was dropping endlessly into an abyss.

The girl swung round and gasped with amazement at the wall of moonlit water rearing over them. At the instant that it threatened to engulf them, the boat slewed, and then seemed to climb almost vertically up the slope. The vicious, curling tip of the comber hissed past, only inches below the gunwale, and then on the downward tilt, the wind snatched her breath, whistling in her ears and howling across the foam-flecked surface of the water to flick tongues of spume from the waves. "I thought you said the weather had calmed down!" she shouted, flinging herself forward and cowering down in the shelter of the bulk head beside the boy.

He was hunched over the wheel, his wet eyes bright in the moonlight, anticipating every movement with small motions of the spokes, tiny variations in the opening of the throttle. There was a smile on his lips.

This, April saw at once as she repeated her comment, was a young man doing what he wanted to do: pitting his skills against the elements.

He turned and grinned at her. "I said the wind had dropped. But I warned you there was a sea running, mind," he yelled back.

"There still seems plenty of wind to me!"

"Oh, come now – she's not a point over Force Six! These seas are about eighteen foot, trough to crest. It's when they're shorter that you're in trouble: front half liftin' before your stern's down, and you break your back as soon as whistle!"

The bows corkscrewed through a crest crumbling into foam, hung giddily over space, and then roared down into a trough, to thunder against the swell of the next wave with a shock that sent showers of icy spray exploding into the air. Drenched to the skin, the girl pushed the soaking hair from her eyes and screamed against the wind: "Do you think you can make it to your cave in this kind of weather, Ernie?"

"Sure I can. We have to head out a bit because of the reefs inshore this side of the point. But there's slack water off Tregunda, and it runs powerful deep just there, which is why the old smugglers used it. It's when you get big seas on a shallow ground that it's dangerous... like the Manacles, off Coverack. That's beyond the headland on the far side of the cove: you can see the flashing light as we rise.... There! See! They've had more wrecks there than the rest of the coast put together."

"Okay, Ernie. You're the skipper. if you think you can – Good grief! Look at that!"

A mountainous wave rose at them crosswise, canting the boat alarmingly on her beam. At the same time another breaker speeding diagonally across its face burst with a noise like a thunderclap over the stern, cascading a torrent of sea water into the cockpit. April picked herself up groggily from the duckboards, to hear Ernie shouting: "Bail, woman! bail for your life! Get that water out or we're done for next time we hit a sea like that!"

"What... with? What shall I bail with?" she screamed against the howling of the wind.

Ernie Bosustow was wrestling with the wheel, steering the bucking whaler up and down the gigantic seas like a man on a roller-coaster. "...old petrol tin... stern thwart... fast as you..." she heard him shout.

She found a two-gallon can with the top sawn off under the rear seat, and began frenziedly dipping and throwing, dipping and throwing, as they ploughed on into the gale. The next half hour was sheer nightmare. As soon as they were far enough out to clear the reefs, they had to circle round and run back before the wind, with the great combers, marbled grey and gold by the moon, sweeping past on either side. The whaler, squatting low in the water now that she was half awash, alternately buried her nose and her stern in the crests as the twin screws – now labouring, now racing as they lifted clear of the sea – slogged remorselessly on. Many times, as they sank endlessly into some trough, she was sure they would never rise again; many times, as the boat shuddered to the onslaught of an extra large wave, she was certain it would disintegrate.

![Книга [The Girl From UNCLE 01] - The Birds of a Feather Affair автора Michael Avallone](http://itexts.net/files/books/110/oblozhka-knigi-the-girl-from-uncle-01-the-birds-of-a-feather-affair-228781.jpg)

![Книга [The Girl From UNCLE 01] - The Global Globules Affair автора Simon Latter](http://itexts.net/files/books/110/oblozhka-knigi-the-girl-from-uncle-01-the-global-globules-affair-170637.jpg)

![Книга [The Girl From UNCLE 03] - The Golden Boats of Taradata Affair автора Simon Latter](http://itexts.net/files/books/110/oblozhka-knigi-the-girl-from-uncle-03-the-golden-boats-of-taradata-affair-107109.jpg)