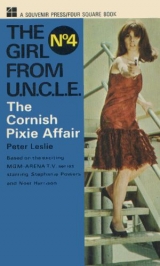

Текст книги "[The Girl From UNCLE 04] - The Cornish Pixie Affair"

Автор книги: Peter Leslie

Жанры:

Боевики

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 10 страниц)

"Oh, no," the girl laughed. "Cape Cod's quite wild sometimes, weather-wise, but Maine's much quieter than this – and anyway both of them are far more... well, kind of cosy, than this. Nearer to the stockbroker belt, too. This is so empty and so big!" She flicked aside her hair with an imperious jerk of the head and settled back in the seat. "You'd better fill me in (I think that's what Waverly said) on the rest of the details. What was this bit about your local squire's wife being a complaisant one, by the way?"

"Willco. Roger and out," Slate drawled in a burlesque Oxford accent. "Some investigators are made, not born – and this bird just dropped into my lap, as you might say. Not literally, of course. Not during office hours. But she did drop."

"Perhaps a little background first," April prompted.

"Right. Well, there's this chap… kind of a squire type – clean-limbed, rakish face, old but good tweeds, early middle-age. And the gent appears to have been doing a line with our Sheila, dazzling her with his worldliness and so forth. So much so that her fiancé, the son of the circus, has a stand-up row with her about the man, threatening to do her in if she doesn't cut the said squire out. So much so that S.S. himself is the prime suspect in the eyes of many, he being the last person to have seen her alive."

"What would his motive have been – according to these many?"

"Well, that's just it, love. To stop his wife finding out about une petite affaire that had become too clinging and too troublesome – and therefore too dangerous. Only as it happened she knew already. And didn't mind, as I say."

"Now tell me how you know that."

"I was sitting in the Crabber last night – that's the pub where I'm staying – and I got into conversation with this woman. You know how it is."

"Yes," April said. "I know how it is."

"She was very much the county type – tall, you know, with that kind of ageless fair hair and rather well made-up. Good figure. Good conversationalist – and quite witty, too, as a matter of fact —"

"What was she wearing?" April interrupted.

"Waisted tweed jacket over a white polo-neck sweater, with jodhpurs and a cute little velvet cap. I think she had been out riding."

"You must be joking! ...Still, that would no doubt make the point she wanted to give satisfactorily."

"Look, you haven't even seen... Oh, never mind! Anyway, the conversation veered round to the local murder. All conversations here do, as you'll no doubt find out! And she said something like: 'Gerry – that's my husband – was rather fond of the girl. They used to see a lot of each other and they'd been as thick as thieves for months.' And I said: 'But don't you mind?' And she said no, she and her husband had an Understanding; each could go their own way, she said, and make whatever friends they liked. And if anyone specially attracted them, she said, they were free to react as they wished. And then she asked could she buy me a drink..."

"Oh, Mark, Mark!" April laughed. "Don't ever change, will you?" -

"Well, anyway, when I found out from the barman that 'Gerry' was Sir Gerald Wright, suspect number one in the case, and that he and his wife lived in a big house on the moors above the town, well, I thought it prudent to sit tight and hear what she wanted to tell me."

"How do you mean – what she wanted to tell you?"

"Well, all this was very nice – but it was just the tiniest bit contrived, you know. The dear lady came into the bar and sat down three tables away from me. She went to powder her nose – and when she came back she sat down only two tables away. Later she went to the bar itself and returned to ensconce herself at the next table to mine. And then, when a waiter came up, she asked him a question she knew very well he couldn't answer – but I could. Something about London. Naturally, he turned to me to ask. Naturally I replied – and there we were, talking. It was beautifully done, but it was a set-up."

"I see," April said slowly. "And what do you think it was that she wished to plant on you? The fact that her husband had no motive for murdering Sheila?"

"No, I don't think so. After all, how could she possibly know that I was investigating the killing – or even that I was interested in it? My mate Superintendent Curnow would have been the obvious recipient for that line."

"True. Perhaps she just arranged the meeting for the obvious reason: your animal attraction."

"You're very kind. But seriously, I believe she did have an – er – ulterior motive—"

"That's what I just said."

"– other than the obvious one. And I think she has already achieved her objective."

"What do you mean?"

"I mean, I think the bit about her husband and Sheila was simply a conversational gambit – one of several she made – and that the real purpose of the operation was just to scrape an acquaintance with me."

"But why, Mark?"

"We shall know later. Phase One was to get to know me. Having gained that objective, she was too clever to press further. But I'm certain that, in some way or another, the acquaintance is going to be exploited soon."

"You realize what that would imply, though, don't you?" April objected. "If anybody bothers to employ a subterfuge to get to know you – apparently just a newspaperman on assignment – then they must know, or suspect, that you are not what you appear to be."

"There's a possibility that I may be blown already. I know." He sighed.

"But good heavens, how? Who could possibly have found out?"

"That's what we have to find out, April."

"Yes. And that brings us back to Square One, doesn't it? If they – whoever they are – do know about you, then the woman might have had a reason for sowing the idea that her husband couldn't have killed Sheila, don't you see? For in that case she would in fact know that you were investigating the murder."

Slate was silent for a few minutes as he drove the car expertly through a series of tight bends which followed the course a stream along the bottom of the valley. He was frowning when he spoke again. "You're quite right, of course," he said. "The corollary is so simple that it had escaped me. But it adds up to the same thing: we must view any future contacts with the lady – or with her husband, for that matter – as potentially dubious. For the time being, at any rate... And that brings me to a suggestion I was going to make regarding your own modus operandi."

"Which is?"

"That as we have to allow for the possibility that I may be blown, it's obviously going to be much better if there's no apparent connection between us. If I'm suspect, obviously any stranger I'm seen with is also suspect."

"Of course."

"So, although it's going to be inconvenient, I propose that we act as though we had never met, once we get to Porthallow."

"Pass each other in the street with our respective noses in the air?"

"Precisely."

"Make like our beautiful friendship had never been?"

"Even so."

"Well, in that case you'd better drop me off somewhere before we get there, so that I can arrive independently by bus or something."

"If you bail out in one of the back streets of Helston and catch a bus, there's a train from London that you could have come by, a few minutes earlier," Mark said. "The bus will land you in Porthallow at four-thirty... Look, there's the fishing village called Mousehole down there. You can see why it's on every Cornish picture postcard and souvenir ashtray in the book, can't you! We'll be in Penzance in a few minutes."

He went over his actions since he had arrived from London, hour by hour, as they threaded their way through the grey streets of the town, skirted the great bay islanding the fortress village of St. Michael's Mount, and drove past the bleached waste of Prah Sands.

"But tell me, Mark," the girl asked – they had turned inland now, across the checkerboard of farming country where the sky above the bare branches was black with rooks – "tell me about these two attempts on your life. Do you think they were made just because you were with the policeman? Has anyone tried to get at him? Or do you read them as further evidence that you're blown?"

"Oh, Point Number Three. Definitely. The more I think about it, the more I'm convinced. Even in the short time I've been talking to you about the affair, I've become practically certain of it. And anyway, nobody has taken a pot-shot at Curnow, so why try to bend an unknown assistant unless you have some further reason for rubbing him out?"

"Yes, that makes sense, I'm afraid. Have you found out anything about the attempts themselves? How they were worked, I mean."

"As much as one can. The shattered window on the car has been taken out – witness the draught howling in over my arm! – and I retrieved the slug from the door trim on the other side. I don't want to tip off Curnow that there's anything out of the ordinary about me – at least not yet – and so I can't very well get the bullet to a ballistics expert down here. From my own limited knowledge of the subject, I should judge that the gun was an express rifle, as I suspected – probably a Mannlicher – that it had been fired something over a thousand yards away, and that, if you produced the line between the place where the bullet lodged in the door and the opposite window where it entered, it would slant up over the tents to the moor above the town."

"And would the place where this line hit the moor be a thousand yards away?"

"Give or take a hundred in each direction, yes. But it doesn't really help: there's an awful lot of moor, and a great deal of it's a thousand yards away from the circus field! A two degree error in the arrival line of the slug – even if I'd estimated it, which I didn't – would give you a quarter of a mile or more up among those rocks. It was useless looking – and it could have been anybody, anyway. Anybody but Curnow, that is: he was with me!"

"And the case of the rolling stone?"

"Easier to pinpoint what happened; just as difficult to pin it to a person. The boulder was one of those local rocking stones. It had been perched about fifty yards above the road, on the hillside – just far enough for it to get up speed as it burst through the hedge and took the bank. Someone had worked it almost over with crowbars – you can see the marks in the turf – so that the smallest push would topple it down the slope when required."

"But how did they know when it would be required?" she frowned.

"Given the fact that my cover is blown in some way, it's not so very mysterious. First, they would be watching me any way. Secondly, if it was known that I was professionally interested in Sheila's death, it was a reasonable bet that I'd be going to see her fiancé – and the lane is the only road to his hut, where he spends most of his time. Thirdly, I hadn't been especially discreet about hiding the fact that I wanted to see the boy – at that time, there was no need to be. Fourthly, this car is somewhat distinctive and the lane is in full view of the place where the rock was. All they had to do, once they knew I'd be going there, was wait."

"Even so, it's a pretty crude, imprecise method of trying to… I mean, compared with a high-powered rifle, it's a bit of a hit or miss —"

"I know what you mean," Mark interrupted. "But it's not all that bad if you think of it merely as a means to try and frighten someone off."

"Oh, you think that's what it was?"

"I think it might be. The rifle shot could have been a deliberate near-miss for the same reason. When you think of it, the boulder idea is so melodramatic, so unscientific, so unlikely to succeed because there are so many variables – the car's speed, the boulder's speed, the terrain, the direction, for example – that it would seem absurd for anyone to try it if they seriously wished to kill or maim their victim. In particular for the sort of person who dreamed up the rifle idea and the coconut-shy routine."

"I see. Any idea of the perpetrator, just the same?"

"It's wide open. Practically the whole town used that road yesterday afternoon for some reason! It leads to the Coverack road over the Tor."

"Could they all have done the trick with the stone?"

"Most of them could! The hut where the fiancé turns his Serpentine lighthouses is a couple of hundred yards away; Wright's house is just over the brow of the hill, looking towards the radar station; Curnow used the lane only a few minutes before me, on his way to St. Keverne; the landlord of the pub brought some stuff down it in a shooting brake just after lunch. Even the Harbourmaster was out walking, it seems!"

"How many of them could physically have done it, time wise?"

"Provided they had already loosened the boulder in anticipation, any of them."

"Oh, dear," the girl said. "Dead end. What do you suggest then?"

"I suggest you leave that to me. It'll already be known that I'm meddling in something, anyway. So far as you're concerned... What did you say your cover was?"

"I hadn't yet. New Zealand girl, ex-university graduate, ex-barmaid, working her way round the world, on the lookout for any employment. Waverly hoped the antipodean bit might excuse any departures from the norm in my English accent!"

"But that's perfect!" Mark exclaimed. "Old Bosustow was complaining every five minutes how difficult it would be to find someone to take over the booth Sheila had, at this time of the year. With that background, you can quite legitimately go and see him and ask if he's any work. You've come to the southwest because London's too cold for you in the winter.

"And when he says he hasn't anything, but there's a concession you could operate – well, you can say you have a little money saved, or offer to pay later, or give him a percentage of the take... anything, so long as you don't appear too eager. Then, if only you could get installed in Sheila's place, we could take it from there: the booth's as good a place as any to start, so long as we restrict any double appearances, as it were, to after dark! Maybe we could even solve the mystery of the burglars who take nothing!"

"Yes. I think that's a good idea," the girl said. "At least, I'll give it a try. Where did Sheila live, by the way?"

"She rented a small two-berther from the old man. I guess you could have the same caravan if the deal comes off. And talking of coming off, here's where you'd better think of getting off. This is Helston."

The streets of the market town were bordered by wide channels carrying the brick-red waters of a stream, and after the granite and slate of Penzance the whole place seemed warm and pinkly bustling in the afternoon light. April extricated herself from the Matra-Bonnet's passenger seat, reached in for her suitcase and the black crocodile handbag, and leaped nimbly across the surging gutter to the sidewalk.

"You can pick up the bus down the first side street to the left," Mark called as he leaned over to shut the door. "It'll be labelled 'Falmouth via Porthallow' – and the fare'll cost you half a crown – if you know what that is!"

"Thanks. I'll keep in touch by radio – but you watch out for ladies in jodhpurs in bars!" the girl called.

There was a momentary squeal as the wide Michelins bit into the asphalt, two small puffs of smoke – and the blue car was rocketing towards an intersection and the main road to Falmouth and the east.

CHAPTER SIX: THE CUSTOMER IS ALWAYS WRONG

THERE was nothing to show the casual passer-by that Mark Slate was in the middle of a two-way radio transmission. He sat slumped in the driving seat of his car, apparently gazing idly at the folds of moorland sweeping down to Porthallow and the twin curves of breakwater enclosing its harbour. To the more inquisitive, venturing closer to the lay-by on the slope of Trewinnock Tor where he was parked, he would have presented the picture of a young man intent upon some task for which he had specially stopped. For there was a notebook, open at a page half covered with handwriting, propped against the steering wheel – and he was toying with what looked like a rather fat pen.

What would have been invisible to such a watcher was the thin, telescopic antenna projecting beyond the barrel of the device. For Mark was in fact engaged with April Dancer on a remote-control check of Sheila Duncan's booth at the circus.

After some argument and haggling, the girl had succeeded in persuading the older Bosustow to let her take over the souvenir kiosk temporarily, and now, just after the afternoon opening of the sideshows, she was busy checking the stock. Since she was not supposed to know Mark, and since the booth was too small to conceal anybody, they had decided to maintain radio contact while she was actually there rather than compare notes in secret some time later in the day. "It's really more practical that way," April had argued. "Always better to discuss things as they come up than to try and recall every detail afterwards. And since I can't hide you inside, and you won't have any excuse for lounging about outside because you don't know me, I think our U.N.C.L.E. Communicators are the answer, don't you?" Slate had agreed, stipulating only that his end of the operation should be out in the country rather than in the town, where his actions might be noticed visually, or in his hotel room, where he might be overheard. He listened now to April's description of what she had found on the shelves and in the cupboards of the tiny booth.

"She had stuff in Serpentine, Onyx, Porphyry, Agate and Chrysopase, as far as I can see," she said; "the great majority of it being Serpentine. And it's fairly obvious, both from the books, such as they are, and from the stock, that lighthouses in Serpentine are the best sellers – in all sizes, from a couple of inches high to almost a foot. Next on the list are ashtrays – in the green Serpentine, the red, and in Moss Agate. And after that come various kinds of creatures, Cornish pixies mostly."

"What are they made of?" Mark asked curiously, raising the Communicator to his lips after a cautious glance around.

"Chrysoprase and Onyx, chiefly the former. They're pretty stylised, mind you, with very little detail: none of those minerals lend themselves to the kind of sentimental work that pixies normally demand. And in any case they are not suitable for mass production techniques – even the kind where each item is made separately!"

"Tell me one thing," Mark queried. "What the devil is Chrysopase?"

The voice percolating through the tiny Communicator in his hand sounded amused. "It's a green variety of Chalcedony – which, as I'm sure you must know, is a kind of semi-precious quartz... Apart from these, there are eggcups and small vases in Serpentine, trinket boxes in Serpentine and Agate, and paperweights – very classical in style – made in everything. May I keep you something, sir?"

"What are the pixies like?"

"They look as though they had leprosy."

"Oh. Perhaps I'd better —"

"Hold it Mark," April's voice interrupted. "I have customers. This is the third today. Business is booming! I shall leave the Communicator on so you can hear – but don't for goodness' sake say anything."

He heard a Cornishwoman's voice saying something indistinct. And then April, very clearly: "Yes, they are pretty, aren't they, dear?... No, the big ones are rather expensive, I'm afraid... Three pounds ten... Yes, of course, I understand... These small ashtrays are nice for a casual present; come in handy at any time. And they're only twelve and six. Just as you like... Yes, you do that…"

"No sale, I gather," he said when the girl came on the line again.

"No. I didn't really – Oh. Hold on again. There's this youth has been hanging about for some time: Now he's coming over. Can't say I like the look of him much. Keep quiet... Good afternoon, sir. Can I help?"

This time, the voice was clear and well-defined. A Londoner, or at any rate from the Home Counties, Slate thought. Not too well educated, but self-confident, almost cocky.

"Hullo, love. I'd like a Cornish pixie, please. In black Porphyry."

"In black...? A pixie? Just a moment, I don't think... Will you hold on a minute, sir. I'll just have a look."

Over the diminutive transmitter, Slate heard the sound of whistling overlaid by the opening and shutting of drawers and cupboard doors. And then the girl's voice, puzzled: "I'm so sorry, sir. I'm afraid we don't have any pixies in Porphyry, black or otherwise. Can I interest you in—"

"No, it's a pixie, in black Porphyry," the boy cut in.

"Well, I'm terribly sorry... We do have Porphyry ashtrays. Black and red, as you see. And stud boxes."

"Are you sure you don't have black Porphyry pixies?"

"Well, yes. I've just told you, haven't I?"

There was a short silence, and then the youth's voice mumbling: "Okay, okay. Have it your way. You don't have any. But they definitely said..." The voice died away as he walked out of range of the set.

"That was odd," April's voice said a few minutes later. "Look – there's a big cupboard full of odds and ends at the back of the booth. I think I'll sort through that in the next few minutes. There may be notebooks, papers, or at any rate something of interest to us there.. though if Miss Duncan had been as thoroughly trained as we have to be, I doubt it very much!"

"Okay," Mark replied. "You do that. While you're making a start, I shall take off and move the car somewhere else. I don't want to stay too long in any one place, in case people start noticing. As it is, half the wretched population down here seem to have field glasses!"

He drove back into the town and out along the track skirting the harbour and the bathing beach. On top of the headland separating Porthallow from the adjoining cove, he pulled off the road and stopped the car in a grassy depression. Beyond the clifftop, the white shapes of gulls floated in an up-current of air against the haze merging sea and sky in the winter sun. After he had switched off the engine, he listened to the booming of surf somewhere out of sight below and then drew the Communicator from his pocket and touched the button which would actuate the call-sign bleep on the twin that April had.

"Channel open," the girl's voice came crisply from the tiny speaker.

"Slate. I'm up on the cliffs on the other side of the town."

"Good. I've been busy too. I've sold a small round stud box in Agate since you called, and two lighthouses. Only the smallest, mind, but it's a start, don't you think?"

"Most commendable," Mark said dryly.

"And there's another funny thing too. Remember you heard the boy who asked for a black Porphyry pixie? Well, someone else came up and asked had I one."

"That is odd. Who was it? Did they ask in the same words?"

"A spotty young man of about twenty-two, I should judge. He didn't ask right out. Just wanted to see things in black Porphyry. And when it turned out that there were no pixies, he lost interest and went away."

"So what's so special about pixies in black Porphyry, one wonders? You have checked? There really are none?"

"Yes and no. Respectively."

"April – you don't think this is... a sign?... do you?"

"Like From Above, you mean? Or like an omen, a pointer?"

"Something like a word to the wise."

"Well, of course it did strike me, after the second request, that it might be some kind of coded intro. But what for, I can't think."

"If there were black Porphyry pixies available only to those who asked for them, but not on display, then it might make some kind of sense. But since you say there definitely are none —"

"Wait a minute, Mark," April interrupted. "Perhaps the fact that there are none is itself significant. Suppose, for example, that asking for a black Porphyry pixie was a coded request for something quite different... then surely the last thing they'd have in stock would be such a repellent object, if only to avoid the risk of someone, someone not in the know, asking for one by coincidence and getting told automatically whatever there was to be told."

"I say! I think you may have got something there," Slate exclaimed. "How can we check and find out if it's true? – And, if so, what the coded request leads to?"

"First of all by giving this place a far more systematic going over than I can manage while it's supposed to be open to the public. I suggest we come here secretly tonight, with flashlights and with plenty of time, to see if we can find out what they were up to. That way, too, we can work together without giving the game away – that we know each other, I mean."

"Fine, There is one thing, though, April: you keep mentioning them and they...the last thing they would have in stock; what they were up to; and so on. Whom do you have in mind? The girl in whose kiosk all this is supposed to take place was an U.N.C.L.E. agent – one of us! Was she in on it, do you think? And if so, what on earth was she up to?"

"That's not the least of the mysteries we have to solve... Hold it again! There's someone coming – and it's the old man himself. No less!"

For a moment, Mark heard only the indeterminate background noise of the funfair – voices, laughter, the thwack of coconuts, a glare of jukebox music – as an obbligato to the mewing of gulls. The wind was rising, snatching at the body work of the car and flattening the grey-green leaves of sea pinks on the cliff. Then came the old man's voice, surly as ever: "Good day, Miss Dancer. Gettin' into the swing of it, I hope? Not that there's much around in the way of clientele in this God-forsaken hole in winter. You want to latch on to any foreigners – strangers, that is – that you see and talk them into a sale. Pretty girl like you shouldn't find that too difficult, I guess. But don't waste any time on the locals: they come to stare, not to buy... Sold anything today?"

"Only one or two, I'm afraid" – April's voice was a nicely judged blend of deference and coquetry – "but I managed to shift an Agate stud box and a couple of light houses."

"Which ones?"

"The little ones .. . these."

"You should never sell those if you can help it. If they'll buy those, they'll buy a size larger. Look through the stock until you find one or two of the little ones that are slightly flawed – then put them in the front against the best examples you can find of the more expensive ones. That way, the mugs'll see that the dearer one is worth the difference."

"Suppose they won't stretch to it, Mr. Bosustow?"

"You do your stuff and they will. But if they don't, then sell 'em one of the flawed little 'uns. Of course, if they insist, show 'em the better examples. Any sale's better'n none... but in any case I don't think you're going to get much practice just now! As I say, the locals just won't bite."

"They don't like any of this beautifully turned stuff?"

"Not a thing."

"Not even the pixies in black Porphyry?"

"Pixies in black Porphyry? What are you talking about, girl? That's a damfool thing to say; you can't work pixies out of that kind of material! It'd never take the detail: the crystals are too big and the whole thing's far too brittle. Even my son couldn't do that, and he's the expert. You ask him."

"I'm sorry. It was just that one or two people asked…"

"For Cornish pixies in Porphyry? Black Porphyry? They must have been out of their minds. A lighthouse with a gallery – or perhaps a box with a decorated lid – that's about as far as you can go with that!... Anyway, you keep trying. I'm – er – I'm in my trailer if you should want me for any reason."

"Does my womanly intuition deceive me, or was that the germ of a proposition?" April demanded when she came back on the line again.

"Hardly knowing the man, I couldn't say. But knowing you, love... well, you draw your own seamy conclusions," Mark chuckled. "At least one thing is clear, though: there are no pixies in that stone. So we need waste no time looking for them tonight."

"That's right. What we do have to do, though, is find something else – something to which a request for a Porphyry pixie might provide a lead... Look, Mark: I must go for a moment. The wind seems to be getting up and there's a side flap here that'll be out of control unless I fasten it down now. I'll be with you in a minute

While he waited, Mark Slate got out of the car and took the Communicator with him to the cliff top.

The breeze had indeed freshened appreciably, even in the short time since he had parked. His trousers plucked at his calves as he stood on the lip of a sheer face of granite plunging two hundred and fifty feet to the sea. The water was grey now, the division between sky and ocean even less precise, and around the rocks which pierced the swell sucking at the base of the headland angry crests were already creaming into explosions of spray. To one side, geological aeons ago, a fault had sliced away half the bill, which now leaned precariously into the waves with its stepped sides a foam with sea birds.

The buffeting of the wind in his ears, and the thin shrilling of air through the vegetation at first masked the call-sign on the Communicator, and the instrument had bleeped three times before his mind registered the sound.

"Sorry!" he called, the device close up against his lips as he glanced around once more to make sure that nobody was near. "I was just verifying that there seems to be a storm blowing up, and the atmospherics drowned you out at first! Have you fixed your canvas?"

"Yes, I have. I don't know if it's the thought of warmth and light at the end of what looks like becoming a bad afternoon, but there seems to be quite a crowd drifting in now, in twos and threes. We'd better make plans for our rendezvous later, in case we don't have the chance to talk again."

"Okay," Mark said. "You're the lady. You choose."

"Right. I'll be here in the caravan he's let me have. Most of them – judging by last night – put out their lights quite early. The place closes at ten. There's an hour's television while they eat. And then that's it... Give them an hour to settle, and we can start."

"It looks like the witching hour, then?"

"Check. To make doubly sure, you leave your pub at twelve. You'll have the car in the garage there, I suppose, and come on foot?... Right. The walk should take you about ten or twelve minutes, so allowing for getting in, I guess we'd be safe to make a date at the booth for twelve-twenty. Okay?"

![Книга [The Girl From UNCLE 01] - The Birds of a Feather Affair автора Michael Avallone](http://itexts.net/files/books/110/oblozhka-knigi-the-girl-from-uncle-01-the-birds-of-a-feather-affair-228781.jpg)

![Книга [The Girl From UNCLE 01] - The Global Globules Affair автора Simon Latter](http://itexts.net/files/books/110/oblozhka-knigi-the-girl-from-uncle-01-the-global-globules-affair-170637.jpg)

![Книга [The Girl From UNCLE 03] - The Golden Boats of Taradata Affair автора Simon Latter](http://itexts.net/files/books/110/oblozhka-knigi-the-girl-from-uncle-03-the-golden-boats-of-taradata-affair-107109.jpg)