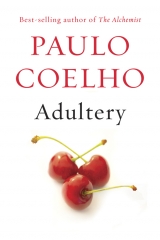

Текст книги "Adultery"

Автор книги: Paulo Coelho

Жанр:

Современная проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 4 (всего у книги 12 страниц)

“If you don’t want to go and see a doctor, why don’t you do some research?”

I’ve tried. I’ve spent ages looking at psychology websites. I’ve devoted myself more seriously to yoga. Haven’t you noticed the books I’ve been bringing home lately? Did you think I’d suddenly become less literary and more spiritual?

No, I’m looking for an answer I can’t find. After reading about ten of those self-help books, I saw that they were leading nowhere. They have an immediate effect, but that effect stops as soon as I close the book. They’re just words, describing an ideal world that doesn’t exist, not even for the people who wrote them.

“But do you feel better now?”

Of course, but that isn’t the problem. I need to know who I’ve become, because I am that person. It’s not something external.

I can see that he’s trying desperately to help, but he’s as lost as I am. He keeps talking about symptoms, but that, I tell him, isn’t the problem. Everything is a symptom. Can you imagine a kind of spongy black hole?

“No.”

Well, that’s what it is.

He assures me that I will get out of this situation. I mustn’t judge myself. I mustn’t blame myself. He’s on my side.

“There’s light at the end of the tunnel.”

I’d like to believe you, but it’s as if my feet are stuck in concrete. Meanwhile, don’t worry, I’ll keep fighting. I’ve been fighting all these months. I’ve been in similar situations before, and they’ve always passed. One day I’ll wake up and all this will just be a bad dream. I really believe that.

He asks for the bill, he takes my hand, we call a taxi. Something has gotten better. Trusting the one you love always brings good results.

JACOB König, what are you doing in my bedroom, in my bed, and in my nightmares? You should be working. After all, it’s only three days until the elections for the Municipal Council and you’ve already wasted precious hours of your campaign having lunch with me at La Perle du Lac and talking in the Parc des Eaux-Vives.

Isn’t that enough? What are you doing in my dreams? I did exactly as you suggested; I talked to my husband, and I felt the love he feels for me. And afterward, when we made love more passionately than we have in a while, the feeling that happiness had been sucked out of my life disappeared completely.

Please go away. Tomorrow’s going to be a difficult day. I have to get up early to take the children to school, then go to the store, find somewhere to park, and think up something original to say about a very unoriginal topic—politics. Leave me alone, Jacob König.

I’m happily married. And you don’t even know that I’m thinking about you. I wish I had someone here with me tonight to tell me stories with happy endings, to sing a song that would send me to sleep. But no, all I can think of is you.

I’m losing control. It’s been a week since I saw you, but you’re still here.

If you don’t disappear, I’ll have to go to your house and have tea with you and your wife, to see with my own eyes how happy you are. To see that I don’t stand a chance, that you lied when you said you could see yourself reflected in me, that you consciously allowed me to bring the wound of that unsolicited kiss upon myself.

I hope you understand. I pray that you do, because even I can’t understand what it is that I’m asking.

I get up and go over to the computer, intending to Google “How to get your man.” Instead, I type in “depression.” I need to be absolutely clear about what’s happening.

I find a website with a self-diagnosis questionnaire titled “Find Out if You Have a Psychological Problem.” My response to most of the questions is “No.”

Result: “You’re going through a difficult time, but you are definitely not clinically depressed. There’s no need to go to a doctor.”

Isn’t that what I said? I knew it. I’m not ill. I’m just inventing all this to get some attention. Or am I deceiving myself, trying to make my life a little more interesting with problems? Problems require solutions and I can spend my hours, my days, my weeks, looking for them. Perhaps it might be a good idea, after all, if my husband asked our doctor to prescribe something to help me sleep. Perhaps it’s just the stress of work that’s making me so tense, especially since it is election time. I try so hard to be better than the others, both at work and in my personal life, and it’s not easy to balance the two.

TODAY is Saturday, the eve of the elections. I have a friend who says he hates weekends because when the stock market is closed he has no way to amuse himself.

My husband has persuaded me that we need to get out of the city. His argument is that the kids will enjoy a little trip, even if we can’t go away for the whole weekend because tomorrow I’m working.

He tells me to wear my jogging pants. I feel embarrassed going out like that, especially to visit Nyon, the ancient and glorious city that was once home to the Romans but now has fewer than twenty thousand inhabitants. I tell him that jogging pants are really something you wear closer to home, where it’s obvious that you’re intending to exercise, but he insists.

I don’t want to argue, so I do as he asks. I don’t want to argue with anyone about anything—not now. The less said, the better.

While I’m off to a picnic in a small town less than half an hour away, Jacob will be visiting voters, talking to aides and friends, and feeling nervous, perhaps a little stressed, but glad because something is happening in his life. Opinion polls in Switzerland don’t count for much, because here secrecy of the vote is taken very seriously; however, it seems likely that he’ll be reelected.

His wife must have spent a sleepless night, but for very different reasons from mine. She’ll be planning how to receive their friends after the result is officially announced. This morning she’ll be at the market in Rue de Rive, where, all week, stalls selling fruit and cheese and meat are set up right outside the Julius Baer Bank and the shop windows of Prada, Gucci, Armani, and other designer brands. She chooses the best of everything, without worrying about the cost. Then she might take her car and drive to Satigny to visit one of the many vineyards that are the pride of the region, to taste some of the new vintages, and to decide on something that will please those who really understand wine—as seems to be the case with her husband.

She will return home tired, but happy. Officially, Jacob is still campaigning, but why not get things ready for the evening? Oh, dear, now she realizes that she has less cheese than she thought! She gets in the car again and goes back to the market. Among the dozens of varieties on display, she chooses the cheeses that are the pride of the Canton of Vaud: Gruyère (all three varieties: mild, salé, and the most expensive of all, which takes nine to twelve months to mature), Tomme Vaudoise (soft and creamy, to be eaten in a fondue or on its own), and L’Etivaz (made from the milk of cows grazed in alpine pastures and prepared in the traditional way, in copper cauldrons, over open wood fires).

Is it worth popping in to one of the shops and buying something new to wear? Or would that appear ostentatious? Best to wear that Moschino outfit she bought in Milan when she accompanied her husband to a conference on labor laws.

And how will Jacob be feeling?

He phones his wife every hour to ask if he should say this or that, if it would be best to visit this street or that area, or if the Tribune de Genèvehas posted anything new on its website. He depends on her and her advice, offloads some of the tension that builds up with each visit he makes, and asks her about the strategy they drew up together and where he should go next. As he suggested during our conversation in the park, the only reason he stays in politics is so he doesn’t disappoint her. Even though he hates what he’s doing, love lends a unique quality to his efforts. If he continues on his brilliant path, he will one day be president of the republic. Admittedly, this doesn’t mean very much in Switzerland, because as we all know, the president changes every year and is elected by the Federal Council. But who wouldn’t like to say that her husband was president of Switzerland, otherwise known as the Swiss Confederation?

It will open doors, bring invitations to conferences in far-flung places. Some large company will appoint him to its board. The future of the Königs looks bright, while all that lies before me at this precise moment is the road and the prospect of a picnic while wearing a hideous pair of jogging pants.

THE FIRST thing we do is visit the Roman museum and then climb a small hill to see some ruins. Our children race around, laughing. Now that my husband knows everything, I feel relieved. I don’t need to pretend all the time.

“Let’s go and run round the lake.”

What about the kids?

My husband spots a couple family friends sitting on a nearby bench, eating ice cream with their children. “Should we ask them if our kids can join? We can buy them ice cream, too.”

Our friends are surprised to see us, but agree. Before we go down to the shore of Lake Léman—which all foreigners call Lake Geneva—he buys the ice cream for the children and asks them to stay with our friends while Mommy and Daddy go for a run. My son complains that he hasn’t got his iPad. My husband goes to the car and fetches the stupid thing. From that moment on, the screen will be the best possible nanny. They won’t budge until they’ve killed terrorists in games more suited to adults.

We start running. On one side are gardens; on the other, seagulls and sailboats making the most of the mistral. The wind didn’t stop on the third day, nor on the sixth. It must be nearing its ninth day, when it will disappear and take with it the blue sky and the good weather. We run along the track for fifteen minutes. We’ve left Nyon behind us and had better head back.

I haven’t exercised in ages. When we’ve been running for twenty minutes, I stop. I can’t go on. I’ll have to walk the rest of the way.

“Of course you can do it!” encourages my husband, jogging in place so as not to lose his rhythm. “Don’t stop, keep running.”

I bend forward, resting my hands on my knees. My heart is pounding; it’s the fault of all those sleepless nights. He keeps jogging circles round me.

“Come on, you can do it! It’s worse if you stop. Do it for me, for the kids. This isn’t just a way of getting some exercise, it’s reminding you that there’s a finish line and that you can’t give up halfway through.”

Is he talking about my “compulsive sadness”?

He stops jogging, takes my hands, and gently shakes me. I’m too tired to run, but I’m too tired to resist as well. I do as he asks. We run together for the remaining ten minutes.

I pass billboards for the various Council of States candidates, which I hadn’t noticed before. Among the photos is one of Jacob König, smiling at the camera.

I run more quickly. My husband is surprised and speeds up. We get there in seven minutes instead of ten. The children haven’t moved. Despite the beautiful surroundings—the mountains, the seagulls, the Alps in the distance—they have their eyes glued to the screen of that soul-sucking machine.

My husband goes to them, but I keep running. He watches me, surprised and happy. He must think his words have had an effect and are filling my body with the endorphins that fill our blood whenever we do some physical activity with a slight intensity, like when we run or have an orgasm. The hormones’ main effects are improving our mood, boosting our immune system, and fending off premature aging, but, above all, they provoke a feeling of euphoria and pleasure.

However, that isn’t what the endorphins are doing for me. They’re merely giving me the strength to carry on, to run as far as the horizon and leave everything behind. Why do I have to have such wonderful children? Why did I have to meet my husband and fall in love? If I hadn’t met him, I’d be a free woman now.

I’m mad. I should run straight to the nearest mental hospital, because these are not the kinds of things one should think. But I continue to think them.

I run for a few more minutes, then go back. Halfway, I’m terrified by the possibility that my wish for freedom will come true and I’ll find no one there when I go back to the park in Nyon.

But there they are, smiling at their loving mother and spouse. I embrace them all. I’m sweating, my body and mind dirty, but still I hold them close.

Despite what I feel. Or, rather, despite what I don’t feel.

YOU don’t choose your life; it chooses you. There’s no point asking why life has reserved certain joys or griefs, you just accept them and carry on.

We can’t choose our lives, but we can decide what to do with the joys or griefs we’re given.

That Sunday afternoon, I’m at the party headquarters doing my professional duty. I managed to convince my boss of this, and now I’m trying to convince myself. It’s a quarter to six and people are celebrating. Contrary to my fevered imaginings, none of the elected candidates will be holding a reception, and so I still won’t get a chance to go to the house of Jacob and Marianne König.

When I arrive, the first results are just coming in. More than forty-five percent of the electorate voted, which is a record. A female candidate came out on top, and Jacob came in an honorable third, which will give him the right to enter government if his party chooses him.

The main hall is decorated with yellow and green balloons. People have already started to drink, and some make the victory sign, perhaps hoping that tomorrow their picture will appear in the newspaper. But the photographers haven’t yet arrived; after all, it’s Sunday, and the weather is lovely.

Jacob spots me at once and immediately looks the other way, searching for someone with whom he can talk about matters that must, I imagine, be extraordinarily dull.

I need to work, or at least pretend to. I take out my digital recorder, a notebook, and a felt-tip pen. I walk back and forth, collecting statements such as “Now we can get that law on immigration through” or “The voters realize that they made the wrong choice last time and now they’ve voted me back in.”

The winner says: “It was the female vote that really counted for me.”

Léman Bleu, the local television station, has set up a studio in the main room, and its female political presenter—a vague object of desire for nine out of ten men there—is asking intelligent questions but receiving only the sound bites approved by the political aides.

At one point, Jacob König is called for an interview, and I try to get closer to hear what he’s saying. Someone blocks my path.

“Hello, I’m Madame König. Jacob has told me a lot about you.”

What a woman! Blond, blue-eyed, and wearing an elegant black cardigan with a red Hermès scarf, although that’s the only famous brand name I can spot. Her other clothes must have been made exclusively by the best couturier in Paris, whose name must be kept secret in order to avoid copycat designs.

I try not to look surprised.

Jacob told you about me? I did interview him, and, a few days later, we had lunch together. I know journalists aren’t supposed to have an opinion about their interviewees, but I think your husband is a brave man to have gone public about that blackmail attempt.

Marianne—or Mme König, as she introduced herself—pretends to be interested in what I’m saying. She must know more than she is letting on. Would Jacob have told her what happened during our meeting in the Parc des Eaux-Vives? Should I mention it?

The interview with Léman Bleu has just begun, but she doesn’t seem to be interested in listening to what her husband says. She probably knows it all by heart, anyway. She doubtless chose his pale blue shirt and gray tie, his beautifully cut flannel jacket, and the watch he’s wearing—not too expensive, to avoid appearing ostentatious, but not too cheap, either, to show a proper respect for one of the country’s main industries.

I ask if she has anything to say. She replies that as an assistant professor of philosophy at the University of Geneva, she would be delighted to comment, but as the wife of a reelected politician, that would be absurd.

It seems to me that she’s provoking me, and so I decide to pay her back in kind.

I say I admire her dignity. She knew her husband had had an affair with the wife of a friend and yet she didn’t create a scandal. Not even when it appeared in the newspapers just before the elections.

“Of course not. When it’s a matter of consensual sex without love, I’m in favor of open relationships.”

Is she insinuating something? I can’t quite look into the blue beacons that are her eyes. I notice only that she doesn’t wear much makeup. She doesn’t need to.

“In fact,” she says, “it was my idea to get an anonymous informer to tell the newspaper the week before the elections. People will soon forget a marital infidelity, but they’ll always remember his bravery at denouncing corruption even though it could have had serious repercussions for his family life.”

She laughs at that last bit and tells me that what she’s saying is strictly off the record, of course, and should not be published.

I say that according to the rules of journalism, people should request that something be kept off the record beforethey speak. The journalist can then agree or not. Asking afterward is like trying to stop a leaf that has fallen into the river and is already traveling wherever the waters choose to take it. The leaf can no longer make its own decisions.

“But you won’t repeat it, will you? I’m sure you don’t have the slightest interest in damaging my husband’s reputation.”

In less than five minutes of conversation, there is already evident hostility between us. Feeling embarrassed, I agree to treat her statement as off the record. She notes that on any similar occasion, she will ask first. She learns something new every minute. She gets closer and closer to her ambition every minute. Yes, herambition, because Jacob said that he was unhappy with the life he leads.

She doesn’t take her eyes off me. I decide to resume my role as journalist and ask if she has anything more to add. Has she organized a party at home for close friends?

“Of course not! Imagine how much work that would be. Besides, he’s already been elected. You hold any parties and dinners before an election, to draw votes.”

Again, I feel like a complete imbecile, but I need to ask at least one other question.

Is Jacob happy?

And I see that I have hit home. Mme König gives me a condescending look and replies slowly, as if she were a teacher giving me a lesson:

“Of course he’s happy. Why on earth wouldn’t he be?”

This woman deserves to be drawn and quartered.

We are both interrupted at the same time—me by an aide wanting to introduce me to the winner, she by an acquaintance coming to offer his congratulations. It was a pleasure to meet her, I say, and am tempted to add that, on another occasion, I’d like to explore what she means by consensual sex with the wife of a friend—off the record, of course—but there’s no time. I give her my card should she ever need to contact me, but she does not reciprocate. Before I move away, however, she grabs my arm and, in front of the aide and the man who has come to congratulate her on her husband’s victory, says:

“I saw that mutual friend of ours who had lunch with my husband. I feel very sorry for her. She pretends to be strong, but she’s really very fragile. She pretends that she’s confident, but she spends all her time wondering what other people think of her and her work. She must be a very lonely person. As you know, my dear, we women have a very keen sixth sense when it comes to detecting anyone who is a threat to our relationship. Don’t you agree?”

Of course, I say, showing no emotion whatsoever. The aide looks impatient. The winner of the election is waiting for me.

“But she doesn’t have a hope in hell,” Marianne concludes.

Then she holds out her hand, which I dutifully shake, and she moves off without another word.

I SPEND the whole of Monday morning trying to call Jacob’s private mobile number. I never get through. I block his number, on the assumption that he has done the same with mine. I try ringing again, but still no luck.

I ring his aides. I’m told that he’s very busy after the elections, but I need to speak to him. I continue trying.

I adopt a strategy I often have to resort to: I use the phone of someone whose number will not be on his list of contacts.

The telephone rings twice and Jacob answers.

It’s me. I need to see you urgently.

Jacob replies politely and says that today is impossible, but he’ll call me back. He asks:

“Is this your new number?”

No, I borrowed it from someone because you weren’t answering my calls.

He laughs. I imagine he’s surrounded by people. He’s very good at pretending that he’s talking about something perfectly legitimate.

Someone took a photo of us in the park and is trying to blackmail me, I lie. I’ll say that it was all your fault, that you grabbed me. The people who elected you and thought that the last extramarital affair was a one-off will be disappointed. You may have been elected to the Council of States, but you could miss out on becoming a minister, I say.

“Are you feeling all right?”

Yes, I say, and hang up, but only after asking him to send me a text confirming where and when we should meet tomorrow.

I feel fine.

Why wouldn’t I? I finally have something to fill my boring life. And my sleepless nights will no longer be full of crazy thoughts: now I know what I want. I have an enemy to destroy and a goal to achieve.

A man.

It isn’t love (or is it?), but that doesn’t matter. My love belongs to me and I’m free to offer it to whomever I choose, even if it’s unrequited. Of course, it would be great if it were requited, but if not, who cares. I’m not going to give up digging this hole, because I know that there’s water down below. Fresh water.

I’m pleased by that last thought: I’m free to love anyone in the world. I can decide who without asking anyone’s permission. How many men have fallen in love with me in the past and not been loved in return? And yet they still sent me presents, courted me, accepted being humiliated in front of their friends. And they never became angry.

When they see me again, there is still a glimmer of failed conquest in their eyes. They will keep trying for the rest of their lives.

If they can act like that, why shouldn’t I do the same? It’s thrilling to fight for a love that’s entirely unrequited.

It might not be much fun. It might leave profound and lasting scars. But it’s interesting—especially for a person who, for years now, has been afraid of taking risks and who has begun to be terrified by the possibility that things might change without her being able to control them.

I’m not going to repress my feelings any longer. This challenge is my salvation.

Six months ago, we bought a new washing machine and had to change the plumbing in the laundry room. We had to change the flooring, too, and paint the walls. In the end, it looked far prettier than the kitchen.

To avoid an unfortunate contrast, we had to replace the kitchen. Then we noticed that the living room looked old and faded. So we redecorated the living room, which then looked more inviting than the study we hadn’t touched for ten years. So then we went to work on the study. Gradually, the refurbishment spread to the whole house.

I hope the same doesn’t happen to my life. I hope that the small things won’t lead to great transformations.

I SPEND quite a long time finding out more about Marianne, or Mme König, as she calls herself. She was born into a wealthy family, co-owners of one of the world’s largest pharmaceutical companies. In photos on the Internet she always looks very elegant, whether she’s at a social or sporting event. She’s never over– or underdressed for the occasion. She would never, like me, wear jogging pants to Nyon or a Versace dress to a nightclub full of youngsters.

It’s possible that she is the most enviable woman in Geneva and its environs. Not only is she heiress to a fortune and married to a promising politician, she also has her own career as an assistant professor of philosophy. She has written two theses, one of them—“Vulnerability and Psychosis Among the Retired” (published by Editions Université de Genève)—for her doctorate. And she’s had two essays published in the respected journal Les Rencontres,in whose pages Adorno and Piaget, among others, have also appeared. She has her own entry in the French Wikipedia, although it’s not often updated. There she is described as “an expert on aggression, conflict, and harassment in the nursing homes of French-speaking Switzerland.”

She must have a profound understanding of the agonies and ecstasies of being human—so profound that she was not even shocked by her husband’s “consensual sex.”

She must be a brilliant strategist to have succeeded in persuading a mainstream newspaper to believe in her, an anonymous informer. (They are normally never taken seriously and are, besides, few and far between in Switzerland.) I doubt that she identified herself as a source.

She is a manipulator who was able to transform something that could have proved devastating to her husband’s career into a lesson in marital tolerance and solidarity, as well as a struggle against corruption.

She is a visionary, intelligent enough to wait before having children. She still has time. Meanwhile, she can build the career she wants without being troubled by babies crying in the middle of the night or by neighbors saying that she should give up her work and pay more attention to the children (as mine do).

She has excellent instincts, and doesn’t see me as a threat. Despite appearances, the only person I am a danger to is myself.

She is precisely the kind of woman I would like to destroy pitilessly.

Because she is not some poor wretch without a resident’s permit who wakes at five in the morning in order to travel into the city, terrified that one day she’ll be exposed as an illegal worker. Because she isn’t a lady of leisure married to some high-ranking official in the United Nations, always seen at parties in order to show the world how rich and happy she is (even though everyone knows that her husband has a mistress ten years her junior). And because she isn’t the mistress of a high-ranking official at the United Nations, where she works and, however hard she tries, will never be recognized for what she does because “she’s having an affair with the boss.”

She isn’t a lonely, powerful female CEO who had to move to Geneva to be close to the World Trade Organization’s headquarters, where everyone takes sexual harassment in the workplace so seriously that no one dares to even look at anyone else. And at night, she doesn’t lie staring at the wall of the vast mansion she has rented, occasionally hiring a male escort to distract her and help her forget that she’ll spend the rest of her life without a husband, children, or lovers.

No, Marianne doesn’t fit any of those categories. She’s the complete woman.

I’VE BEEN sleeping better. I should be meeting Jacob before the end of the week—at least that’s what he promised, and I doubt he would have the courage to change his mind. He sounded nervous during our telephone conversation on Monday.

My husband thinks that the Saturday we spent in Nyon did me good. Little does he know that’s where I discovered what was really troubling me: a lack of passion and adventure.

One of the symptoms I’ve noticed in myself is a kind of psychological nearsightedness. My world, which once seemed so broad and full of possibilities, began to shrink as my need for security grew. Why could that be? It must be a quality we inherited from when our ancestors lived in caves. Groups provide protection; loners die.

Even though we know that the group can’t possibly control everything—for example, your hair falling out or a cell in your body that suddenly goes crazy and becomes a tumor—the false sense of security makes us forget this. The more clearly we can see the walls of our life, the better. Even if it’s only a psychological boundary, even if, deep down, we know that death will still enter without asking, it’s comforting to pretend that we have everything under control.

Lately, my mind has been as rough and tempestuous as the sea. When I look back now, it’s as if I am making a transoceanic voyage on a rudimentary raft, in the middle of the stormy season. Will I survive? I ask, now that there is no going back.

Of course I will.

I’ve survived storms before. I’ve also made a list of things to focus on whenever I feel I’m in danger of falling back into the black hole:

· Play with my children. Read them stories that provide a lesson for them and for me, because stories are ageless.

· Look up at the sky.

· Drink lots of iced mineral water. That may seem simple, but it always invigorates me.

· Cook. Cooking is the most beautiful and most complete of the arts. It involves all our five senses, plus one more—the need to give of our best. That is my preferred therapy.

· Write down a list of complaints. This was a real discovery! Every time I feel angry about something, I write it down. At the end of the day, when I read the list, I realize that I’ve been angry about nothing.

· Smile, even if I feel like crying. That is the most difficult thing on the list, but you get used to it. Buddhists say that a fixed smile, however false, lights up the soul.

· Take two showers a day, instead of one. It dries the skin because of the hard water and chlorine, but it’s worth it, because it washes the soul clean.

But this is working now only because I have a goal: to win the heart of a man. I’m a cornered tiger with nowhere to run; the only option that remains is to attack.

I FINALLY have a date: tomorrow at three o’clock in the restaurant of the Golf Club de Genève in Cologny. It could have been in a bistro in the city or in a bar on one of the roads that lead off from the city’s main (or you might say only) commercial street, but he chose the restaurant at the golf club.