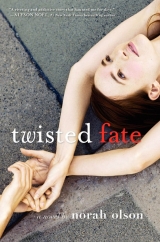

Текст книги "Twisted Fate"

Автор книги: Norah Olson

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 4 (всего у книги 14 страниц)

My mother told me not to marry an older man who had a child. Too big a restoration project, she said. But I never believed her. The truth is I fell in love with both of them. David brought Graham to an opening I had in Washington, DC. David was, of course, charming as usual, impeccably dressed. Tall, thin, handsome. He was a scientist and worked for the government, but he seemed so sweet, so human. It was wonderful to watch him with Graham.

I could see right away what a smart little boy Graham was, and creative. I knew that I could give him something he was missing—not just a mother, but maybe a way of looking at the world. I bought him his first camera when he was seven, and he took pictures of other kids. He took pictures of me and David. And later we got him the video camera. Made sure he had something to occupy himself, help him understand the world around him and make use of it.

My work began selling well and I had money coming in and was able to get a bigger studio. I had work bought by the National Gallery, in London. It was right around then that David asked me to marry him, and that’s when my mother said, Don’t do it. You’ve got your career, you don’t need anybody to look after you. But that was precisely why I did marry David! Unlike her generation, I was getting married by choice. I didn’t need a man to support me. I could do whatever I wanted, and I wanted a family—one that I didn’t need to start from scratch. I didn’t want to take time out of my career to be pregnant and have a baby, and here was a child I could help out, because he needed a mom.

Later, when we would go to my mother’s house in Connecticut for Thanksgiving, she fell in love with little Graham too. That’s the way it was. He wasn’t shy then. He was my little protégé, learning everything there was about how film worked and the visual world. And he was his father’s son—learning everything about battles and strategies and looking at the world from a scientific distance. David worked for BAE Systems as a military aerospace strategist, based just outside of Washington in Virginia. But he was a simple man at heart, with good taste. He still loved to set up the telescope in the yard, and we would all lie out there together looking at the stars. Graham loved that most of all. He would ask millions of questions about how far away the planets were, was there life out there, how did light travel. It was only natural that he became who he was. Mechanically inclined, an artist, a boy who looked at the stars. Someone who thought about war and life and death.

I wish he’d never had to think so deeply about these things. We thought he was in good hands with Dr. Adams and on the new prescription. We thought the art helped his healing. The work he made . . . beautiful stuff, I have to say—even though I’m biased. The lawyer for the other family wanted to have his camera taken away permanently as part of the conditions of his probation, but of course, that was absurd. There was no way that was going to happen, I mean, I really put my foot down on that, and we had the lawyers to make sure he got out of there without some humiliating damaging sentence. He was a child! Sixteen is still a child! People don’t know what they’re doing at sixteen. If anything, the fact that he was trying to make art from a bad situation—I mean, that his initial response was to turn something terrible into something he could understand—was the most human thing that came from all of it.

Anyway, this new work had a maturity to it I don’t think I’ve ever seen in a young artist. Especially the work he did in Rockland. Scenes from bridges, long camera shots with the telephoto lens. Things you can barely make out but that seem intimately familiar. Interviews with people intercut with digital feedback. It’s all very exciting.

I think Graham had been a lonely kid this past year and he needed to process and understand what he went through. I think that was true the last year in Virginia too. I won’t have people saying it was the art—that it was the art that caused all our sorrow. The truth is some of his art is the only consolation. It’s the only thing that still remains.

I saw her waiting as usual in her black jeans, that alert, funny, “I’m about to be in trouble” look on her face. “Tate!” I called to her, and she looked up and grinned sheepishly, walked in, and sat down as I shut the door. This was becoming a pretty common ritual with Ms. Tate.

I try to be a good example, but my office is pretty cluttered. They keep us busy at RHS and I had stacks of folders nearly dwarfing my desk. I always kept a jar of black licorice candy out for students, which for some reason was still three-quarters full.

“Tate, how’s things?” I asked, and then went on without waiting for her usual smart-aleck answer. “I got this report here from your social studies teacher that says you’ve already missed six classes this quarter. What’s up, girl?”

“Six classes? Sure you’re not talking about my sister?”

“Ha! C’mon, don’t give me that line again. I mean it, what’s up? You’re a straight-A student at risk of failing because of absences, detentions, and mouthing off. Doesn’t quite make sense somehow. What can we do to fix it?”

She shrugged. “It’s sixth period. Sometimes I take a long lunch.”

I laughed. “Oh, I hear you, sometimes I want to take a long lunch too, but you know what?”

“What?” Tate asked.

“I don’t.”

Tate didn’t know what to say for once. She smiled awkwardly and shrugged. I really liked this kid. She was one person who I thought about when the last bell rang. Wondered how she was doing and if she was going to make it out of Rockland High okay.

I leaned in close to her and whispered. “I’m going to tell you a secret,” I said. “Everyone kinda hates high school. Unless they are a little bent. But once you’re out, you’re out, and it’s a whole new world. You fail social studies, I mean, you do something stupid and just stop showing up, and you’re gonna miss getting to that new world fast. You’ll end up trapped somewhere you can’t stand for even longer. Does that make sense?”

She rolled her eyes. I’d been telling her similar things last year too, until she came in with a list of successful high-school dropouts and handed it to me. “I hung this over my desk at home,” she’d said. “Thought you might want a copy.” Still, I wasn’t about to give up trying. I got it about why she didn’t want to be in school. She wanted to live in the world instead of sit at a desk. And she didn’t know why she had to show up at all if she was getting good grades. And nobody had yet been able to make her see the logic in it. I also knew Tate got high, which, honestly, as long as she still did her work and didn’t become a slacker, I didn’t really care that much about. The thing I wanted her to do was show up. I wanted her to pass. I’d seen enough kids go through the system, and seen enough friends still working at Pizza Hut, to know that there were plenty of ways some seemingly innocuous drug could drag you down, but Tate’s problem was being there at all.

“Well, look,” I told her. “Whether it makes sense or not, promise me you’ll go to class tomorrow. Okay?”

“Okay,” she said. She looked up and nodded at me. “All right.”

Tate left the office but lingered around outside. She really didn’t want to go back to class—there were only fifteen more minutes anyway, and she could just as easily study a little right now by herself. And besides, something about hanging around Richards’s office made her feel more relaxed. Syd liked Richards because she often saw her smoking on the way from the parking lot to the school, had a loud musical laugh that you could hear in the hallways, and wore black skinny jeans every day. Jeans and a pretty designer blouse. You could tell she didn’t want to dress up at all.

And Tate could easily picture her wearing black lipstick and a ball-chain necklace back when Richards was in high school herself. Now the woman wore a small string of pearls every day, but Syd considered it just a professional costume. She knew that Ally actually admired the pearls and blouse—tried to dress like that herself. Ally described her as “caring but professional,” and Syd had to admit it was a good description. There was something about Richards that both girls liked.

Syd sat on the floor across the hall, where she could still look through the door. She watched Richards pull a file out of her drawer and look at it.

Principal Fitzgerald peeked his head into her office. And Syd watched from the hallway—waiting for him to tell her to get back to class—but he didn’t seem to see her at all.

“Still pondering the fate of Tate?” he asked her.

Richards looked up. “She’s a good kid, Dan,” she said.

“That’s the attitude we hired you for, Mandy.”

“She is, though. I really think she could go on to a top ten. If something besides skateboarding could hold her interest for more than a week and she’d get herself to classes.” She played absently with her pearls as she looked back down at the file. “Her standardized-test scores are high. Her teachers say this kid could be half there or dominate the class, bringing in all kinds of information or doing special reading or extra-credit projects. She’s smart as hell. And she’s always got that joke, ‘You must be thinking of my sister,’ when she’s getting in trouble or getting particular praise. She’s an interesting kid. Mercurial.”

Syd could feel her heart beating harder listening to their conversation. She wanted to hear more and wanted to get up and leave before they said anything that might be upsetting or weird.

Fitz put his hand on the doorframe and leaned there. “Yeah,” he said. “Her best friend Declan—maybe he’s her boyfriend—has the same attitude. Kid’s an incredible wiseass but clearly headed to Harvard. He’s one of those geniuses who goes on to be a professor or gets scooped up to work on a government project. I wish they could be like their friend Becky. She’s such a sweetheart, never in trouble.”

“C’mon, Dan, it’s harder for some people to pull off that intellectual rebel thing. Declan gets away with more because he’s a boy. Becky has a little more poise for some reason, I suspect ’cause she gets a little more parenting. But Tate’s got a lot of pressure. Hell, you know it’s still a harder world for girls, and for some reason this kid with everything going for her is making it even harder on herself.”

“And she’s been making it harder on herself for years,” Fitzgerald said.

“Anybody ever have a nice long talk with her parents?” Richards asked.

He shook his head and laughed. “If we could track them down,” he said, and Syd felt butterflies in her stomach and the hair on the back of her neck go up as he talked about her parents. “Funny family,” he said, scratching his head. “Never available. Rarely home. Her father’s a builder. Salt-of-the-earth, back-country Mainer who made good. But y’know, sometimes even I can barely understand what he’s saying. Accent so thick. The money comes from her mother’s side, and that family owns half the state. Apparently they met when Mrs. Tate was home from college and he was doing some work on one of her parents’ houses in Kennebunk. Or that’s the gossip, anyway. Can’t say I’ve been able to have a decent conversation with either one of them. Even back when Tate started that fire in the chemistry lab freshman year. I told them about it—the mother said, ‘I see,’ and a week later we had an anonymous gift for state-of-the-art lab equipment. But no change in the kid’s behavior at all.”

Richards shook her head. “That is the last thing in the world a kid like that needs. No consequences.”

“Tell me about it,” Fitzgerald said. “Between her and Declan we got just about no authority. It’s hard to tell kids their grades will suffer if they screw off when the two of them are like the poster boy and girl for the benefits of having an attitude problem. Sure to be valedictorian and salutatorian—one or the other of them, and they’re both little pains in my ass. Never seen anything like it.”

“Trick is to keep them busy,” Richards said. “Find a way to direct them, maybe.”

“Well, that’s true for Declan,” Fitzgerald said. “Soon as the Model UN or chess club starts he’s out of everyone’s hair for a while and his detentions go down. But Tate? She’s a special case. You’ll see, Mandy, you’ll see.”

00:00–13:42—Swing set

15:04—Cheerleading practice

18:51—Pine Grove Inn

Dear Lined Piece of Paper,

If they would let me stay home from school, I could get so much done! Already in the days since we’ve moved here I feel like I am on to something that’s made me feel better than ever. It might be the drugs, sure, of course it could be the new drugs, especially given the fact that I’ve decided to adjust my own dosage! Not sure how Dr. Adams calculates these things but I was reading online and actually nothing major will happen to my liver if I take even four times as much as they have me on. That means FOUR TIMES as relaxed. And FOUR TIMES as focused and FOUR TIMES better at getting everything done. So it might be the drugs but I think it’s actually a whole new way of thinking about life!

I always believed it was best to see life from a distance, record it from a distance. And then watch it. We think we remember the way things are but we don’t. That’s why I don’t even understand why I’m supposed to go to Dr. Adams. If he wants to know what happened he can just look at the footage. How am I supposed to talk about what I remember from years ago? Those things might not be accurate. Anyway, now I think I can get it right. I just need the perfect subject. I need the perfect character. I need someone who is brave and sweet and full of life, like Eric! I need a partner! And I know just the person. I don’t know how I’ll be able to put the camera down to go to school. But I figure I can get myself a smaller camera. Something tiny I can carry on a lanyard. Something people won’t even notice. I’m not just trying to document my life. I’m trying to make sure I know who I am. And that when that moment comes again I’ll be able to capture it perfectly. The problem with people as far as I’m concerned is they make up these phony personas. They walk around trying to make sure no one knows who they are—wearing whatever everyone else does, listening to whatever music is on the radio, but who are they really? They create whole fake versions of themselves for Facebook.

But on film—in the way I film them—there is a point where the facade breaks down, where you can see who they really are. What I’m giving people is a gift! And it’s a gift I want for myself too! I want to know who I am. I don’t think I’ve ever felt all that scared—shy, yes; pathologically shy, maybe, according to some—but scared? No way. Maybe someday I’ll be able to scare myself, but so far it hasn’t happened. When it happens I’ll have it on film, that’s for sure. I’ll be able to see exactly what it looks like when whatever facade I’ve created for myself breaks down. Even if I don’t know it’s there. There’s something inside of me and I feel like I am closer to getting to it than I’ve ever been before. Four times closer. LOL.

The main thing now is I need more money so I can do all this stuff without asking Dad and Kim to buy me equipment. Fortunately due to my superior reasoning (FOUR TIMES BETTER REASONING SKILLS) I’ve worked out THE PERFECT WAY to make some cash. I’ve set up a PayPal account and also an Amazon wish list so that people who download my films can pay me directly or buy me what I need and then just ship those things to me. You would not believe how interested people are in my films. It’s amazing to me that I’m not already some kind of international superstar. I am like Quentin Tarantino and Stanley Kubrick all rolled into one.

So anyway, Kim is home all day but she’s in her studio working and she has never once brought in the mail that I know of. So no one will know if I get packages or not. When I finish this project it will all make sense to everyone. Especially to me. I will understand things the way I couldn’t before.

Between “finding my calling,” as Dr. Adams would say, and working on the Austin Healey, I think life in Rockland is shaping up to be okay. And the neighbors! Beautiful Tate! I want to talk to her. I want to see her. I want to make her the star of all my films!!

We were baking muffins together, which I have to admit only happened when Syd was high and in a good mood and there wasn’t already a lot of junk food in the house. She’d convince me to make them and then we’d hang out in the kitchen. I guess it was one of the rare times we got along these days. And even though I didn’t like her getting high all the time she could be silly and fun to be around when it was just the two of us.

Anyway, so there we were at the counter and we saw him from the window.

“You going to invite your crush over?” Syd asked, grinning at me.

I shrugged but before I could say anything she had opened the kitchen window and was yelling. “Hey! Justin Bieber, you wanna hang out?”

He looked up and I tried to push my hair away from my face but my hands were all covered with flour and I got it in my hair and he started laughing.

“My sister has something for you,” she said, and then started laughing as well. Great, I thought, she’s going to be so stoned she’ll embarrass me. Like the time she thought it would be a good idea to invite Declan and Becky over for a dinner we made together and then before we could eat she insisted we listen to the same four lines of a song she liked over and over and over again. Because it was “so cool.”

But it was too late; Graham walked up the back steps and came right into the house.

“Looks like you’re having a fun time this afternoon,” he said. I could feel my face flush.

He took the mixing bowl and wooden spoon from my hands and started stirring. And I sat on the counter watching him.

Syd took the bowl from him, set it on the table, and became her usual bossy self. “Sit down,” she told him. “I want to read your palm.” She grabbed his hand and held it in her lap.

Syd of course did not know how to read palms at all. This was just the way she flirted with boys. If they were dumb, she read their palms; if they were smart, she’d challenge them to a game of anagrams.

“Or maybe you’d like to play anagrams instead?” I said to Graham. I never really got why they liked it—that game where you rearrange letters in a word. She and Declan played it all the time and it had them rolling on the ground laughing. By doing the palm-reading thing, she was telling me she thought Graham was dumb, but she was also getting to touch him, which I was sure she wanted. I sat down next to them.

“Oh, do you know how to play anagrams?” Syd said, stroking his palm lightly.

Graham said, “Ah . . . I kinda do, actually.”

“Okay, we’ll start with Eiffel Tower,” Syd said. “Go.”

He stared for a while and then asked for a piece of paper. She grinned a triumphant sort of grin and actually placed his hand into mine. Then she got up and sat on the counter, humming and mixing the batter, laughing to herself.

It felt good to hold his hand. It was wide and strong and his fingers were long and beautiful. I thought about him working on his car. “I don’t really know how to read palms,” I told him. “But I can tell we’re all going to be friends.” I looked up and smiled and he nodded, his face flushed. Now he really did look nervous, shy. I felt my stomach flutter.

“I better finish making these,” I said, going to the counter and taking the bowl out of Syd’s hand.

“You sure are an interesting girl,” he said, and his eyes were shiny, gleaming beneath the yellow kitchen lights as dusk fell outside.

I had just a few hits of the bowl on my way home with Declan and Becky and was suddenly feeling very in the mood for some sister time in the kitchen and I didn’t have to wait long. When I got home Ally was already standing at the counter, looking at a recipe book and twirling her long blond hair absently around her finger.

“Graham’s coming over,” she said. “I invited him over to make muffins with us.”

“Oooooh. You’re really making the moves on your crush,” I said.

“Stop it, Syd. He’s new here and we’re his neighbors and we should be nice to him.”

“Fine by me,” I said. “As long as you’re baking.”

I reached into the bowl of blueberries and ate a few and she slapped my hand playfully.

We watched Graham lope across the driveway into our backyard and up the steps and then he knocked.

“Hi!” Ally said, opening the door for him. I saw how he looked at her, that way some guys had where they were totally captivated by her homespun New England princess ways. And it made me smile. He looked like kind of a dork next to her, but he was also painfully good-looking.

“You wanna help mix the batter?” Ally asked.

“Yeah,” he said. “Sure. Ah, could I use the bathroom for a minute?”

“I’ll show you where it is,” I told him. “You kinda got to go through a construction site. To get to it.” Ally looked up at me sharply. She didn’t like me saying anything negative about our house, but it was true, Dad’s tools were everywhere and I’d rather say it myself than hear someone else point it out.

He followed me though the living room and out to the front hall. I sat on the piano bench while he went into the bathroom. He didn’t shut the door. And then I heard a faint scraping, crunching sound. I wondered what he could be doing. I tiptoed into the hallway and peered around the corner. In the reflection of the mirror, I could see him cutting up a white pill. There were three other pills laid out on a hand mirror he’d clearly found in the cabinet.

“What are you doing?” I asked him.

He turned around, startled. “I . . . this . . .” He handed me a prescription bottle. “This is my anxiety medication,” he said. “Sometimes when I feel nervous I, ah . . . snort it. Because it, ah . . . it works faster.”

I took the bottle and it was indeed a prescription made out to him. The pills also looked the same as the ones in the bottle. I stared at him. I felt kind of sorry for him, but it was also too weird. This kid was into some things I couldn’t quite understand. Part of me wanted to understand them a lot better and part of me wanted him to leave.

“My sister really wouldn’t like that,” I told him.

“No,” he said slowly, looking deeply into my eyes. “She seems very different from you.”

“It’s okay,” I said. “I won’t tell her.”