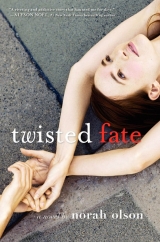

Текст книги "Twisted Fate"

Автор книги: Norah Olson

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 14 страниц)

DEDICATION

For Sebastian

CONTENTS

Dedication

Sydney

Allyson

Graham

Sydney

Syd

Ally

Police Chief Bill Wertz

Syd

Ally

Syd

Graham

Syd

Kim Ray

Amanda Richards

Graham

Ally

Syd

Ally

Becky

Syd

Ally

Syd

Syd

Ally

Police Chief Cody Daly

Ally

Syd

Graham

Ally

Syd

Syd

Police Chief Bill Wertz

Syd

Graham

Syd

Ally

Graham

Police Chief Bill Wertz

Ally

Kim

Becky

Ally

Syd / Becky

Syd / Declan / Becky / Graham

Ally

Police Chief Bill Wertz

Syd

Graham

Kim

Declan

Syd

Becky

Syd

Syd

Syd

Ally

Police Chief Bill Wertz

Syd

Syd

Syd / Ally / Graham

Police Chief Bill Wertz

Acknowledgments

Back Ad

About the Author

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

I’m not saying that I was right in the end. In fact maybe I’m to blame: the way I was caught off guard; the way I walked out of school that late afternoon with my eyes wide-open, thinking I had a plan, that I could fix everything all by myself, never dreaming how wrong things could go at the harbor.

I had my headphones on and Death Cab for Cutie blasting. I put my board down on the road and skated toward the slips. The autumn air rushed through my hair, and cars whizzed by close enough for me to feel them, and I thought in those moments, giddy and a little high, how I was going to fix things, make everything right in the world. I was going to save us both; protect Ally above everything—even though I could barely stand her half the time, even though we could go for weeks without speaking. But still I was determined to make it all okay. I thought there was no way it could go wrong and so I let myself be happy while I headed to the ocean. And that happiness felt like it was something coming from Ally’s head or maybe Ally’s heart. And I remember in those moments knowing that we were more alike than I ever could have admitted. Knowing that things between us were different, were finally somehow understood. After all, a sister in many ways is like a second self.

Back before it all happened I felt like one of us must have been adopted. Besides being what our mom breezily calls “pretty” when she takes us all dressed up to one of her fund-raisers or parties, we don’t even look alike. Ally has long blond hair that’s straight as a board and green eyes and her skin is milky pale and smooth. For as long as I could remember she’d been the good girl, the standard beauty. And I’ve been her shadow, a photo negative, where all the light spaces, the bright happy spaces, turn to dark. And make no mistake, I am dark. Not just dark thoughts and dark humor. I have dark curly hair, dark eyes, freckles instead of the romantic moonlight-paleness of her face. How we came from the same parents is a complete mystery to me.

If it sounds like I’m jealous of her I’m not. I would not have wanted to live her life or have gone through what she went through in the end. And I’d never in a million years have been naive enough, stupid enough, to become friends with Graham Copeland, part skeleton, part zombie in his expensive Diesel jeans, all blond and pretty like Allyson and too stuck up or shy or obsessed with his own weird world to talk to anyone. I could see right away that something wasn’t right. The way he looked at her, the way he could never look me in the eye quite the same way.

I remember it so clearly, the day that would change our lives forever: watching the moving van pull out of the driveway of the big old post-and-beam house next door. It was the nicest house in the neighborhood. Rockland is full of these places—mansions actually. Perfect old slate-roofed estates waiting for rich folks to move in. Or weathered stately old gems that people fixed up. Even though it was right next to Graham’s, our house was the latter. Rambling and not as square as a place should be. Our dad was a boat builder and he bought it when we were little and fixed it up himself—well, he was still occasionally fixing it up—might be fixing it up forever for all we knew. He was so busy sailing and doing restoration carpentry on other people’s mansions that he wasn’t around a lot and our house didn’t quite get the attention it needed. And that made Mom crazy, or at least gave her a good excuse to have some hysterical meltdown every time she got nervous about her high-society plans: drop cloths in the living room when company was on the way, when she was hosting another ridiculous benefit or kissing up to historical-society ladies. Our mom’s parents would invariably shell out whatever was necessary to make the place exactly what she wanted, but Dad always insisted on doing the work himself—he’d been a carpenter since he was a kid. Even with our nice house Dad’s family was a little too close to the windbeaten lobster-trawling trash our mother liked to pretend didn’t exist. Dad always had sawdust in his hair.

But next door it was a very different story. You could tell once the moving van wasn’t blocking the black Mercedes and the red Audi that were parked in the driveway that the people who moved in wouldn’t be getting much plaster and paint in their hair. I caught all these details right away. Ally of course was out by the wooded edge of our property picking blueberries like she did every Saturday and humming to herself, not having the slightest idea what was going on next door.

She walked over and gave me a handful of blueberries and we stood near the wide-trunked pine in our front yard munching them together. Then a boy came out of the garage and walked between the two fancy cars. We watched him.

He was thin and his shoulders were broad and his hands were covered with engine grease. His hair was an unruly blond mess, his bangs brushed over to the side, and he looked like he’d just woken from a long nap. He had big blue eyes that looked like they were just beginning to focus, like a baby’s eyes, like some kind of dazed animal. He had a wrench in the back pocket of his jeans and you could see his ribs through his shirt.

“Nice hairdo!” I called out to him. He flinched as I said it and started walking quickly to his house, flattening his hair down with his dirty hands. But then Ally called out again. Of course she did—the good girl, the sensitive girl that she was.

“Want some blueberries?” she asked him in that way she had, that sweet way like nothing is ever really wrong. “I just picked them. They’re special welcome-to-the-neighborhood berries.”

She crossed our driveway and handed him the basket. And I watched him standing there, looking at her, then looking down, awkwardly eating blueberries with his dirty hands. Then he smiled. I remember his teeth were unnaturally straight and white and his face was smooth like he didn’t need to shave yet—or like he was one of those guys who might never really need to shave. An angelic face but something else behind his eyes.

“What grade are you in?” she asked him.

I could barely make out what he said because he spoke so quietly.

“I’m taking some time off,” he said, and then cleared his throat as if he weren’t used to talking much. “Ah. I just got here.”

She should have walked back into our yard right then and gone inside. But she stood chatting like she always did. The professional hostess’s daughter. The golden-haired good girl, unable to see what damage looks like, even when it’s staring her right in the face.

That was then. This is now. If you can call this period of time anything at all. It feels like simply waiting. I guess all that exists is the present. We know what the past got us, and the future . . . well, the future is unwritten. All I know is that I’m almost out of time. I’ve got less than twelve hours to save myself and to make sure no one, absolutely no one, has to go through what Ally went through. I’m hoping she told me everything she knew, but given the things I found out—the things I know she didn’t or couldn’t tell me—that seems unlikely. If I could only get the details straight. If only there wasn’t something ominous and terrifying floating just below the water’s surface out by the slips.

But if I’m going to wish, if I’m going to say “if only,” I would go back much further than that. I’d go back to when Ally and me were just kids and I’d fix things before they got bad.

When I go over it in my head I always start with the morning we met Graham.

I was up early helping Mom get the house ready because the ladies from Rockland Historical Society were coming to look at our widow’s walk. Dad had restored it just the way it was in the town’s records from the 1920s and now you could go and stand up there and see the whole harbor; you could actually see some of the boats Dad built out in the slips, tall and majestic, and rocking easily on the cold waves. It was beautiful.

I baked some muffins and made some lemon curd and then helped clear up some of Dad’s junk. One of the ladies visiting that morning was my boss, Ginny Porter, who owned the Pine Grove Inn. I still couldn’t believe I got to have a job in that old mansion. There was a glorious view from nearly every window. On one side you could see the close majesty of tall pines, on the other there were cliffs and the rocky shoreline and the lovely old lonely lighthouse standing tall in the harbor. Because of that job I also got to meet interesting people coming to our town from all over the world. People passing through for a night, or staying for a few days to take it all in. People trying to get away from the city and just relax.

Mom was mortified thinking that our guests would show up early that morning and Daddy would still have his blueprints and models spread all over the dining room, but I was more worried about Sydney, who could be unpredictable when we had company. Either she would say something rude or sulk around in her black skinny jeans and uncombed hair looking like someone owed her something. And if people talked to her God only knew what she’d say. It could be brilliant—like really brilliant, reciting some poem or doing some cool card trick Dad taught us when we were kids—or it could be just plain vicious, calling people snobs or philistines. She loved the word philistine. I’d had to look it up. I never heard anyone but her and maybe my social studies teacher use it. This was the thing with Syd: she seemed all dark and tough and low-class if you didn’t know her, but she spent so much time with her face in a book she had this vocabulary that shocked people. Since we were little she was like this. Anyway, the word means someone who is hostile to culture. Which I think is completely the opposite of Mom’s friends. They all care so much about culture and about the town’s history and about genealogy. But whatever. It’s not like Syd and I ever really saw things the same way.

Sydney was lying around our room in her black tank top reading (of course) and listening to Bright Eyes or Death Cab or some other weird emo band that sounded like they were whining all alone from the bottom of the ocean. Not exactly the right music for ladies deciding if our house will be designated a historic landmark.

I walked in and handed her a muffin on this cute patterned china plate that we used to have tea parties with, and she sat up, her black tangled mane falling around her shoulders. She had her lost-in-another-world look and she was reading a book that sure wasn’t part of the summer reading list for school. Winter’s Bone I think it was, some creepy thing where everyone’s poor and everyone dies. Her side of the room was plastered with posters of the same emo bands plus Brody Dalle from the Distillers, all tattooed and screaming, and a big poster of Tony Hawk upside down above a flight of concrete stairs holding his skateboard, looking like he was about to come crashing down right on Sydney’s bed. Which I’m sure she would have just loved.

“Hey, cutie, can you turn it down a little?” I asked.

“Why?” She yawned. “Those blue-haired mummies won’t be here for hours.”

“Mommy’s trying to concentrate on her presentation.”

“You’re seventeen, Ally. You really should stop calling Liz Mommy.”

“And you should not call Mom Liz,” I told her. “It’s disrespectful.”

“Whatever.” She shut her book and took a bite of the muffin and smiled in spite of herself.

I sat down on the bed and thought I could smell cigarette smoke on her clothes, or worse, pot. Great, I thought, just great. I needed to get her out of the house for a while so she wouldn’t embarrass Mom or say something weird to Ginny.

“C’mon, smarty,” I said, poking her in the sides a little to make her jump. “Let’s go pick some berries.”

She groaned and made a big show of getting up and putting on her shorts.

Syd can be really difficult sometimes but I’ve found that if you get her used to an idea there will be less fighting later on. I hated fighting with her. Honestly, I love her too much and don’t really have the heart for it. Unlike Syd I’ve never really been much of a fighter. I remember seeing her when Mom brought her back from the hospital. Her hands already balled into tiny fists. But her birth was a blessing in so many ways. The year she was born was the year I learned how to say no. And that’s an important skill for a girl to have.

I dragged her out of the room that morning and we went down the back stairs and rummaged in the pantry for baskets and then headed for the wooded edge of our property. Movers were coming and going from the house next door and Syd wanted to spy and see who our new neighbors would be. I left her by the big old pine and went to pick berries by myself. At least she was out of the house.

The next thing I knew she was shouting. I looked up and saw a tall, sweet-looking kid walking out of the garage across the driveway, cleaning his hands on a rag and carrying a neat little tool kit. He was handsome, his neat blond hair parted on the side and swept across his forehead. He had broad shoulders and you could see his muscles and ribs beneath his shirt. He had that same faraway look Syd gets when she’s reading.

“Hey, loser,” Sydney called to him. “Nice haircut. You know most Justin Bieber wannabes are twelve years old, right?”

I could see she’d hurt his feelings, that he was a sensitive boy. He started heading for his house, cleaning what must have been the rest of the engine grease off his hands as he walked between the two fancy cars that were parked in his driveway.

“Wait,” I called. “Wanna come over here and eat some blueberries? We just picked them.”

He stopped and smiled tentatively, tucked the rag into the back pocket of his jeans, and came into our front yard. He smelled clean, like citrus and laundry detergent, and the air around him was cool, as if he had just come out of an air-conditioned room.

Sydney stood close to him, her arms folded across her chest, sizing him up. The sun shone between the needles of our giant pine, creating a beautiful pattern of light across the ground, dappling their faces with sunshine.

“I’m Tate,” she said, in her tough, abrupt way.

He looked at us and then laughed shyly. “I’m Graham,” he told us.

“What books do you read?” she asked him, her chin pointed up defiantly. Just like that. Like it’s all she cared about. And if you weren’t one of her friends—Declan or Becky or some other weird angry brainiac—this could really put you off.

He tossed a handful of blueberries into his mouth and seemed to think about it for a while, too timid to talk. I could tell he was cautious for a reason but I didn’t know what that reason might be.

“Anything about art or movies. Anything cars or driving,” he said finally. “Or ancient cultures . . .” He looked like he was thinking of more subjects and she smiled faintly at him, gave just the tiniest nod of approval.

Apparently, he wasn’t put off at all. It turned out to be the right question. These two will have something to talk about, I thought. I like school but I’m not so interested in heavy reading. I could tell right away he was like Syd. She was the smartest girl in her grade. And the absolute worst for discipline. It was embarrassing for me because they were always calling her down to the office on the PA. I mean rarely a day would go by when there wasn’t some trouble Ms. Tate was getting into. Maybe this kid was going to be a good influence on her, be her friend, I thought as I went back inside and left them talking. I was happy that Sydney was out of the house and out of Mom’s hair and that the shy boy seemed to be okay.

But I know now that this was a mistake. I know that thinking things were fine was the biggest mistake I ever made. It’s hard for me to talk about all this now after what happened. I feel guilty even remembering. Thinking about how I didn’t listen to her. How I ignored everything she said. I guess I was like everyone else, her teachers and her little group of friends at the skate park, Declan and Becky. Everyone thought she was so strong and so smart that she didn’t need anything or anyone. People blamed Graham but they should have blamed me. I should have loved her better. Nothing should have come between us.

Especially not a boy.

4:15—Outside of school playground

7:56—Euclid Avenue parking lot

19:32—Beachfront, slips

23:20—From roof of shed

Dear Lined Piece of Paper,

If I didn’t have this journal I wouldn’t really talk to anyone, so I guess a lined piece of paper is better than nothing. Dr. Adams says anything is better than nothing, but he has yet to convince me. I’ll do my own reading on these subjects.

Okay. Where do I start? They gave my camera back. Obviously. That was a hard one. For a while I thought I might never see it again. But Kim insisted. Because Kim is cool. She gets it. I don’t even know where the hell me and Dad would be if he hadn’t married her. I certainly never would have been able to keep the camera. And once I get the car fixed up I’ll be able to drive it again. I miss driving the most, I guess—just being able to take off and be free and go nowhere.

They say what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger. But this was not what I was thinking back before Rockland, when I tried to see if I could in fact break out of this world and into some dark, cool calm that would let me be happy all the time. I was not going for the “make you stronger” part. I was not going for the “what doesn’t kill you” part. I was going for peaceful silence. To be able to capture that moment between strength and destruction once and for all. I guess I miscalculated a little.

But that doesn’t mean I’ll give up. I can try again. I’m making art, like Kim says. And maybe I can make an even better movie than the one me and Eric made back in Virginia. I’m going to stay dedicated to it no matter how many stupid doctors I have to talk to or new pills I have to try. I am going to get around all these people—the ones who always keep trying to convince you to be a part of their dull world, telling you how important you are and how much you mean to them and how you should get up and go for a walk or go to classes and meet new people, or—the stupidest one ever—“do something that will make you happy.”

And the constant suggestion that I should “try to focus.” Like I can’t focus. I pay more attention than anyone I know—twice the amount of attention, especially if I have my camera with me. Then I’m thinking about how everything is going to look. And when I watch it later I don’t miss a thing. I think that’s the mistake people make—thinking that I’m missing something. I see this world clear as day. I see how everyone plays their part, says what they think other people want to hear. And I see how there are spaces where people are themselves. And that’s where I want to go. I want to see them there. Not in school, not trying to be good around their parents or trying to be an example for their kids or trying to look important at work. There is a time when people are entirely themselves, and that’s what I want to film. That’s the world I want to live in.

What would make me happy is finding another friend like Eric. Eric and I were happy making movies and cruising in the Austin Healey. “Becoming immortal,” he called it sometimes when we were driving fast, shooting the passing countryside. Becoming stars. But like stars in the universe—remote and bright and cold and shining. Real stars.

Nobody was going to make me pay for what I did, but instead of being happy about it, all I could think about was getting it right this time. You know what? Maybe I am stronger now. Maybe I should just say fuck it. Because if I’m honest I don’t know if I even feel like I need to pay for anything at all. Maybe I did for a minute, maybe I do sometimes when I talk to Dr. Adams—not pay I guess but “process,” like he says, and “understand.” But this is what I understand: life’s not fair. And if I’m doing the things that “make me happy” they might be different from what makes everyone else happy.

I lied earlier about having no one to talk to. I met someone today. And she smiled at me in this way that made me feel like she knew me. Like she knew exactly who I was. I would love to be around someone who knew exactly who I was just for even a minute. It would be such a relief. We talked for about half an hour, standing in the driveway, and I could tell she really gets things.

I was almost going to ask her if she wanted to come into the garage and see the Austin Healey.

It’s so close to being fixed.

I do have to give Dad credit for that. Making me fix it myself. And then showing me how. He even had it brought from Virginia so I could keep working on the engine now that I’ve got the body smoothed out and painted.

I thought after the accident that he would freak, that he’d sell it for parts and never let me drive again. My first thought when I saw how much damage it took was that there was no way it’d ever run again, and that was a real disappointment. My first thought was that it was another miscalculation. Another thing Eric and I didn’t see coming. Sometimes I wish we could talk about it. It would really help if I could just ask him a few questions. My second thought was that maybe I was made of steel. Maybe I was unbreakable. I could watch the rest of the world slip away—I could record it—but I was here to stay.

“It’s a lesson,” Dad said.

And Kim, my stepmom, said, “It’s an opportunity.”

Either way the Austin Healey is almost ready to get back on the road, and I’m almost ready to start school again. I’m not sure how I feel about going to this school. But maybe it will be different.

The only thing I miss about Virginia is Eric. I wish I could hang out with him again. Though I can’t say I’m completely sorry about the way things turned out. Eric made me understand who I am. Eric made me know what the world is really like and what I am capable of. And if it weren’t for all the stupid bullshit from his parents, Eric would already be famous.

Maybe I’ll talk to that Tate girl at school. Maybe I can see her alone. I felt when I went back into the new house like I wanted to see her again right away, like I needed to. I went up to my room and looked next door and wondered which window was hers. About an hour later I headed back to the garage and I thought I saw her standing in the big square cupola on top of their house, looking out over the harbor, over the tops of the giant pines.

She was like Helen of Troy, standing up there in the glass room beneath the blue sky with the clouds rolling in from the ocean. I wanted to be able to look at her always. Wanted a film of her just standing there. I could film her doing anything and it would be interesting. Just talking. Just saying nothing.

I could suddenly see how wars could be fought over beauty. And I wanted to film her for the rest of her life.