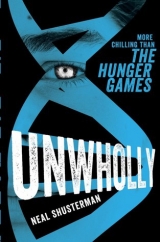

Текст книги "UnWholly"

Автор книги: Neal Shusterman

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 9 (всего у книги 27 страниц)

14 • Dolores

While World War II aircraft enjoy the privilege of permanent museum displays, Korean War fixed-wing aircraft are mostly unloved and forgotten. Since it was the first war to feature extensive use of helicopters, those are the aircraft that get all the attention.

There’s a sorry bomber from the Korean War that sits two aisles off the main aisle. The Admiral put it there, and although Connor has moved planes around it, Dolores, as she is called, never moves and is never opened. Her hatch has been retrofitted with a key lock, and Connor has the only key, which he wears around his neck like a latchkey child.

Dolores is the arsenal. She’s filled with the kind of weapons that troubled teens should not, under any circumstances, have access to. Unless of course they’re in uniform. The idea that the Graveyard would someday have to defend itself like the Warsaw Ghetto hung over the Admiral’s head, and now hangs over Connor’s. There’s not a day he doesn’t think about it—not a day he doesn’t finger that key around his neck like a cross. Today, however, he visits Dolores for another reason—to defend the Graveyard not from attack, but from infiltration. Today he goes in to find himself a .22 caliber pistol and a cartridge of bullets.

15 • Connor

Trace sleeps in a rusty old DC-3, overseeing the roughest, most troublesome kids. It’s an unofficial detention hall, with Trace as the unofficial guard. Since the old propeller plane has a nonfunctioning lavatory, its occupants have to use a portable that sits at the bottom of the gangway stairs. Its lock is broken. Connor broke it a few hours before.

After curfew he and two of the toughest Whollies he could scrounge up wait in the shadows of a neighboring plane, watching.

“Tell us again why we’re taking out Trace?”

“Shh!” Connor tells them, then whispers, “Because I say we are.”

Connor is the only one with a gun. It’s loaded. The goons are just backup, because he knows he can’t take Trace alone. The plan is to corner him, cuff him, and keep him as a sort of prisoner of war . . . but Connor has resolved that he’ll use the gun if it becomes necessary.

Never wield a weapon unless you’re willing to use it, the Admiral once told him. If Connor is going to maintain order in this place, he has to go by the Admiral’s playbook.

Every twenty minutes or so, someone comes out to use the restroom. Trace isn’t one of them.

“Are we supposed to wait here all night?” complains the tough kid holding the cuffs.

“Yes, if we have to.” Connor begins to wonder if Trace’s military training included superhuman bladder control, until Trace comes down a few minutes after midnight.

They wait until the door of the portable closes, and then they quietly approach with Connor in the lead. He puts the pistol in his right hand—Roland’s hand—feeling the coldness of its handle and firmness of its trigger. He takes the safety off, takes a deep breath, and then swings the door open.

Trace stands there, staring right at him, not caught off guard in the least. In a single move he kicks Connor’s legs out from under him, grabs the gun out of his hand, twists him around, and pushes him cheek-first into the dirt, wrenching Roland’s arm painfully behind his back. Connor can feel the seam of the graft threatening to tear loose.

With Connor in too much pain to move, Trace brings down the other two kids before they can run, leaving them unconscious in the dust. Then he returns his attention to Connor.

“First of all,” says Trace, “ambushing a man taking a dump is beneath you. Secondly, never take a deep breath before attacking someone, because it gives you away.”

Connor, still in pain, spins around to face him, and as he does, he feels the muzzle of the gun pressed to his forehead. Trace holds the gun to Connor’s head for a moment more, his face stern, then takes it away. “Don’t feel too bad,” Trace says. “I’m not just an air force boeuf, I was special ops. I could have killed you nine different ways before you hit the ground.” He ejects the clip—but as he does, Connor grabs Trace’s wrist, tugs him off balance, wrenches the gun from him, and aims it at Trace again as he gets to his feet.

“There’s still a bullet in the chamber,” Connor reminds him.

Trace backs away, hands up. “Well played. I guess I’m rusty.” They stand there frozen for a moment, and Trace says, “If you’re going to kill me, do it now—because I will get the advantage again.” But Connor’s resolve is gone, and they both know it.

“Did you kill the other two?” asks Connor, looking at how the once-tough kids lay twisted and unconscious on the ground.

“Just knocked them out. Not much honor in killing the defenseless.”

Connor lowers the gun. Trace doesn’t rush him.

“I want you gone,” Connor tells him.

“Tossing me out will be a very bad move.”

Hearing that just makes Connor angry. “As far as I’m concerned, you’re the enemy. You work for them.”

“I also work for you.”

“You can’t have it both ways!”

“That’s where you’re wrong,” Trace says. “Playing both sides is a time-honored strategy.”

“I’m not your puppet!”

“No,” says Trace, “you’re my commanding officer. Act like it.”

Another kid comes clambering down the stairs to use the portable. He catches sight of Trace and Connor, and the two kids still rag-dolled on the ground. “What’s the deal?” the kid says as he takes in the situation.

“When it’s your business, I’ll tell you,” Connor says.

Then he sees the gun in Connor’s hand. “Yeah, sure, no problem,” he says, and goes back up the stairs.

Connor realizes the distraction would have given Trace plenty of time to turn the tables again, but he didn’t. It moves them one step closer to trust. Connor gestures to Trace with a wave of the gun. “Walk.” But at this point the gun is just a prop, and they both know it. They move farther from the main aisle and down an aisle of mothballed fighter jets. No Whollies here to eavesdrop on their conversation.

“If you work for them,” Connor asks, “then why did you tell me all the things you told me?”

“Because I’m their eyes and ears, but my brain is my own—and whether you believe it or not, I like what you’re doing here.”

“What have you told them about this place?”

Trace shrugs. “Mostly what they already know. That things are under control here. That a new shipment of AWOLs arrives every few weeks. I assure them that the place is not a threat, and no one’s planning to blow up any more harvest camps.” Then Trace stops walking and turns to Connor. “What’s more important are the things I don’t tell them.”

“Which are?”

“I don’t tell them about your rescue missions, I don’t tell them about your escape plan . . . and I don’t tell them that you’re still alive.”

“What?”

“As far as they know, this place is being run by Elvis Robert Mullard, a former security guard from Happy Jack—because if anyone knew that you were the one in charge, the Juvey-cops would raid this place in an instant. The Akron AWOL is too much of a threat for them to ignore. So I make this place sound like a nursery, and I make you sound like a nanny. It keeps them happy, and it keeps all these kids alive.”

Connor looks around them. They’re far from the main aisle now. If Trace wanted to, he could probably break Connor’s neck and bury him, and no one would ever know. Does that mean that Connor actually trusts Trace in spite of his obvious betrayal? He isn’t sure of anything anymore, not even his own motivations.

“None of this changes the fact that you’re working for the Juvey-cops.”

“Wrong again. I don’t work for the Juvies, I work for the people who own them.”

“No one owns the Juvenile Authority.”

“All right, then, maybe not own, but control. You want to talk about puppets? Every single Juvey-cop is on a string they don’t even know about. Of course I don’t know who’s pulling the strings. All I know is that I got taken away from a promising future in the air force and got sent here.”

Connor grins in spite of himself. “Sorry to mess with your career track.”

“The point is, I don’t report to anyone in the air force; I report to civilians in suits, and that ticks me off. So I did a little research and found out that I work for a company called Proactive Citizenry.”

“Never heard of it.”

Then Trace drops his voice to a whisper. “I’m not surprised—they keep a low profile, and that provides a cover that gives the military plausible deniability. Think about it; if the brass don’t know who they’re actually working for, then if something goes wrong, the military can always claim ignorance, court-martial me, and come away clean.”

Now things are becoming a little clearer to Connor, or at least clearer as to why Trace decided to play both sides. They turn and begin walking back toward the main aisle.

“I’m disillusioned, Connor. The way I see it, you’ve been more fair and more trustworthy than whoever it is I work for. Character counts for a lot in this world, and when it comes to Proactive Citizenry, shady doesn’t even begin to describe them. So I’ll do my job for them, but I put my trust in you.”

“How do I know you’re not lying to me now?”

“You don’t. But so far you’ve survived because of your instincts. What do your instincts tell you right now?”

Connor thinks about it and realizes the answer is easy. “My instincts tell me that I’m screwed no matter what I do. But that’s normal for me.”

Trace accepts his answer. “We have more to talk about, but I think that’s enough for one day. You should probably put some ice on that shoulder. I wrenched it pretty hard.”

“I hadn’t noticed,” Connor lies.

Trace reaches out his hand to shake, and Connor considers what shaking that hand means. It could be the creation of their own secret society to battle Proactive Citizenry, whatever that is . . . or it could mean Connor has been entirely duped. In the end, he shakes Trace’s hand, wishing that just once, there could be a clear course of action.

“Before today you were just a pawn doing what they wanted you to do,” Trace tells him. “Deep down you knew it—you sensed it. I hope the truth has set you free.”

16 • Risa

Before her shift begins each morning, Risa spends time beneath the wing of the Rec Jet, chatting with other kids who’ve become her friends. She has more friends here than she did back at the state home, but at the same time she feels more like an older sister than a friend. They revere her like some angel of mercy—not just because she’s the medical authority, but because she’s the legendary Risa Ward, the Akron AWOL’s partner in crime. She suspects they think, deep down, she can heal things that are broken inside.

She used to spend time at the Rec Jet in the evening, after her shift, but the Stork Club put an end to that. She has half a mind to demand equal time for the state wards, but knows that fueling a division of the Graveyard into factions won’t do anything but cause trouble. Thanks to Starkey, there’s enough of that going on without her help.

Farther away, she can see Connor step down from his jet. He walks along the main aisle, head down, hands in his pockets, deep in whatever dark cloud is troubling him today. Immediately he’s set upon by kids who need his attention for one reason or another. She wonders if he ever manages to find a spare second for himself anymore. He certainly doesn’t have it for her.

He looks up and catches Risa’s gaze. She turns away, feeling guilty, as if she’s been spying on him, and chides herself for feeling that way. When she looks up again, he’s heading toward her. Behind her kids have begun to gather in front of the TV. Something on the news has caught their attention. She wonders whether Connor is coming to see what the commotion is about or coming to see her. She’s pleased when it turns out to be the latter, although she tries not to show it.

“Busy day ahead?” she asks him, offering him a slight smile, which he returns.

“Nah, just lying around watching TV and eating chips. I gotta get a life.”

He stands there with his hands in his pockets, looking around, although she knows his attention is on her. Finally he says, “The ADR says they’ll send those medical supplies you asked for in the next few days.”

“Should I believe it?”

“Probably not.”

She knows this is not the reason why he came over to her, but she doesn’t know how to coax things out of him anymore. She knows she has to do something before this distance between them gets ingrown.

“So what’s the problem of the week?” she asks.

He scratches his neck and looks off, so he doesn’t have to look her in the eye. “Sort of the same, and sort of you-don’t-want-to-know.”

“But,” says Risa, “it’s big enough for you to tell me that you can’t tell me.”

“Exactly.”

Risa sighs. It’s already getting hot, and she’s not looking forward to pushing her way to the infirmary jet in the heat. She has no patience for Connor being enigmatic. She’s about to tell him to come back when he actually has something to say, but her attention is snagged by the grumble coming from the crowd around the TV, which has grown since she last looked. Both she and Connor are pulled closer by the gravity of the crowd.

The news report is an interview with a woman, rather severe-looking, and even more severe-talking. Coming in the middle, Risa can’t make heads or tails of what she’s talking about.

“Can you believe it?” someone says. “They’re calling this thing a new life form.”

“Calling what a new life form?” Connor asks.

Hayden is there and turns to both of them. He looks almost queasy. “They’ve finally built the perfect beast. The first composite human being.”

There are no pictures, but the woman is describing the process—how bits and pieces of almost a hundred different Unwinds were used to create it. Risa feels a shiver go as far down her spine as she can feel. Connor must have the same reaction, because he grasps her shoulder, and she reaches up to grasp his hand, not caring which hand it is.

“Why would they do such a thing?” she asks.

“Because they can,” Connor says bitterly.

Risa can feel the heaviness of the vibe around her, as if they’re all watching some awful global event unfolding before their eyes.

“We need to get the escape plan ready,” Connor says. Risa knows he’s talking more to himself than to her. “We can’t do a dry run, because the spy sats will pick it up, but everyone needs to know what to do.”

Risa feels the same blast of communal intuition. Suddenly getting the hell out of the Graveyard sounds like a very good idea. Even without a safe destination.

“Composite human . . . ,” someone grumbles. “I wonder what it looks like.”

“C’mon, haven’t you ever seen Mr. Potato Head?”

There’s a smattering of nervous laughter, but it doesn’t lighten the mood.

“Whatever it looks like,” Risa says, “I hope we never see it.”

17 • Cam

With a finger he traces the lines of his face, down the side of his nose to his cheek. Left, then right. Out from the symmetrical starburst of flesh tones on his forehead, then beyond to the lines that spread beneath his hairline. He dips his finger into the graft-grade healing cream again and spreads it across the lines running down the nape of his neck, his shoulders, his chest, and every other place he can reach. He can feel the tingling as the engineered microorganisms in the cream do their job.

“Believe it or not, the stuff is actually related to yogurt,” the dermatologist told him. “Except, of course, that it eats scar tissue.” It also costs five thousand dollars a jar, but, as Roberta has told him, money is no object when it comes to Cam.

He’s been assured that when treatment is done, he’ll have no scars at all, just hairline seams where every little bit of himself meets.

His cream-spreading ritual takes half an hour, twice a day, and he’s come to enjoy the Zen-like nature of it. He only wishes there were something that would heal the scars in his mind, which he can still feel. He sees his mind now as an archipelago of islands that he labors to build bridges between—and while he’s had great success engineering the most spectacular of bridges, he suspects there are some islands he’ll never reach.

There’s a knock at his door. “Are you ready?” It’s Roberta.

“Reins in your fist,” he tells her.

A pause, and then, “Very funny. ‘Hold your horses.’ ”

Cam laughs. He no longer needs to speak in metaphors—he’s created enough bridges in his mind to bring some normality to his speech—but he enjoys teasing Roberta and trying to stump her.

He dresses in a tailored shirt and tie. The tie’s muted colors, yet bold, fractal pattern, were specifically chosen to project a sense of aesthetic composition; a subliminal suggestion that an artistic whole is always greater than the sum of its parts. He fumbles with the tie. While his brain knows how to tie it, his virtuoso fingers obviously had never learned to do a Windsor knot. He must focus and overcome the frustrating lack of muscle memory.

Roberta knocks again, a little more insistently now. “It’s time.”

He takes a moment to admire himself in the mirror. His hair is just about an inch long now. A virtual coat of many colors; streaks extending out from the focal point of multiple skin tones on his forehead. Blond runs down the middle, blending to amber on both the left and right. Shades of red and brown arc back from his temples, then give way to jet black above his ears, and tight, dark curls at his sideburns. “All the famous hairstylists will be trampling one another to get to you,” Roberta said.

Finally he opens the door before Roberta’s knocking becomes frantic. Her dress is a little more elegant than the slacks and blouse she usually wears, but still very understated. It’s all calculated to keep the focus on him. For a moment she seems annoyed at him, but now that she gets a good look at him, her irritation melts away.

“You look spectacular, Cam.” She smoothes out his shirt and straightens his tie. “You look like the shining star you are!”

“Let’s hope I don’t give birth to complex elements.”

She looks at him quizzically.

“Supernova,” he says. “If I’m a shining star, let’s hope I don’t blow up.” He wasn’t even trying to stump her. “Sorry—it’s just the way I think.”

She gently takes him by the arm. “Come, they’re waiting for you.”

“How many?”

“We didn’t want you to be overwhelmed by your first press conference, so we limited it to thirty.”

His heart beats heavily, and he must take a few deep breaths to slow it down. He doesn’t know why he should be so nervous. They have prepared him with three mock press conferences already, where questions were hurled at him in multiple languages. In each one of those he did just fine—and this time it will be only in English, so he has one less variable to worry about.

This one, however, is real. This time he’s about to be officially introduced to a world that is unprepared for him. The faces he saw at those fake press conferences were friendly ones pretending not to be, but today he will be facing actual strangers. Some will just be curious, others amazed, and some might be flat-out horrified. Roberta told him to expect this. What he’s worried about are the things that not even she can predict.

They walk down the hall to a spiral staircase that leads to the main living room—a staircase he had not been allowed to use for his first weeks, until his coordination improved. Now, however, he could dance his way down those stairs if he chose to. Roberta tells him to wait until she announces him. She goes down first, and Cam can hear the rumble of chattering reporters die down. The lights dim, and she begins her presentation.

“Since time immemorial, mankind has dreamed of creating life,” Roberta begins, her voice amplified and larger than life. Flashes of light reach the top of the stairs. Cam can’t see the images from her presentation, but he knows them. He’s seen it all before.

“But the great mystery of life itself has been elusive,” Roberta continues, “and every dream of creation has ended in humbling failure. There’s a good reason for that. We can’t create what we don’t understand, so until we understand what life is, how can we ever create it? No—instead it is the task of science to take what we already have and build on it. Not create life, but perfect it. So we put forth the question, how can we recombine both our intellectual and physical evolution into the finest version of ourselves, the best of all of us combined? As it turns out, the answer was simple once we knew the right question.” She pauses to build the suspense. “Ladies and gentlemen, I present to you Camus Comprix, the world’s first fully composite human being!”

At the sound of applause, Cam begins his descent down the spiral staircase, posture proud but gait casual. The audience is still in shadows as he descends, and all the lights are focused on him. He can feel the heat of the spotlights, and although he’s in a familiar place, it’s as if they’ve transformed the living room into a theater. He hesitates halfway down, takes a deep breath, and continues, making it seem that his pause was intentional—a photo-op tease, perhaps, because this is one press conference where no cameras are allowed. His presentation to the public is being carefully orchestrated.

The applause gives way to astonishment as the crowd gets a good look at him. There are gasps and whispered chatter as he descends to the microphone. Roberta steps aside, giving him the floor, and by the time she does, there is absolute silence in the room as they all stare at him, trying to process what they’re seeing: a young man who is, as Roberta put it, “the best of all of us.” Or at least the best of various unwound teens.

In the charged silence, he leans toward the microphone and says, “Well, I have to say, you’re a very well put-together group.”

Chuckles all around. He’s surprised by the amplified timbre of his own voice, a resonant baritone that sounds more confident than he actually is. The lights come up over the group of reporters, and with the ice broken, the first hands rise with questions.

“Pleased to meet you, Camus,” says a man in a suit that’s seen better days. “I understand you’re made up of almost a hundred different people—is that true?”

“Ninety-nine to be exact,” Cam says with a grin. “But there’s room for one more.”

The group of reporters laughs again, less nervously than the first time. He calls on a woman with big hair.

“You’re clearly . . . um . . . a unique creation.” Cam can feel her disapproval like a wave of heat. “How does it feel to know you were invented rather than born?”

“I was born, just not all at the same time,” he tells her. “And I wasn’t invented, I was reinvented. There’s a difference.”

“Yes,” says someone else. “It must be quite a weight to know that you’re the first of your kind. . . .”

This line of questioning was addressed in the mock conferences, and Cam knows his answers by heart. “Everyone feels like they’re one of a kind, don’t they? That makes me no different from anyone else.”

“Mr. Comprix—I’m an expert in dialects, but I can’t place yours. You keep shifting in and out of vocal styles.”

Cam hasn’t considered this before. It’s hard enough to put thoughts into words, without thinking about how those words are coming out. “Well, I suppose that all depends on which brain cells I’m wrangling.”

“So then your verbal eloquence came hardwired?”

Again, the kind of question he’s expecting. “If I were a computer, it would be hardwired, but I’m not. I’m a hundred percent organic. Human. But to answer your question, some of my skills came from before, others have come since, and I’m sure I’ll continue to grow as a human being.”

“But you’re not a human being,” someone shouts from the back. “You might be made from them, but you’re no more human that a football is a pig.”

Something about this statement—this accusation—cuts him in an unguarded place. He’s not prepared for the emotion it brings forth.

“Bull seeing red!” Cam says. It comes out before he can funnel it through his language center. He clears his throat and finds the words. “You’re trying to provoke me. Perhaps there’s a blade you’re hiding behind your cape, but it won’t keep you from getting gored.”

“Is that a threat?”

“I don’t know—was that an insult?”

Murmurs from the crowd. He’s made it interesting for them. Roberta throws him a warning glance, but Cam suddenly feels the rage of dozens of unwound kids swelling in him. He must give it voice.

“Is there anyone else out there who thinks that I’m somehow subhuman?”

And as he looks out to the thirty reporters, hands go up. Not just the big-haired woman and the heckler from the back, but others as well. As many as a dozen. Do they really mean it, or are they all just matadors flapping the cape?

“Monet!” he shouts. “Seurat! Close to the canvas, their work looks like splotches of paint. But at a distance you see a masterpiece.” Someone controlling the media screens pulls up a spontaneous Monet, but rather than punctuating his point, it makes his comments seem contrived. “You people are all small-minded and have no distance!”

“Sounds like you’re very full of yourself,” someone says.

“Who said that?” He looks around the crowd. No one will take credit. “I’m full of everyone else—and that’s spectacular.”

Roberta approaches and tries to take over the microphone, but he pushes her away. “No!” he says. “They want to know the truth? I’m telling them the truth!”

And suddenly the questions come like bullets.

“Did they tell you to say all this?”

“Is there a reason why you were made?”

“Do you know all their names?”

“Do you dream their dreams?”

“Do you feel their unwindings?”

“If you’re made of the unwanted, what makes you think you’re any better?”

The questions come so fast and with such intensity, Cam can feel his mind begin to rattle itself into fragments. He doesn’t know which one to answer—if he can even answer any of them.

“What legal rights should a rewound being have?”

“Can you reproduce?”

“Should he reproduce?”

“Is he even alive?”

He can’t slow his breathing. He can’t capture his own thoughts. He can’t see clearly. Voices make no sense, and he can see only parts, but not the larger picture. Faces. A microphone. Roberta is grabbing him, trying to focus him, trying to get him to look at her, but his head can’t stop shaking.

“Red light! Brake pedal! Brick wall! Pencils down!” He takes a deep, shuddering breath. “Stop?” It’s a plea to Roberta. She can make this go away. She can do anything.

“Looks like he’s not wound too tight,” someone says, and everyone laughs.

He grabs the microphone one more time, his lips pressed against it. Screeching. Distorted.

“I am more than the parts I’m made of!”

“I am more!”

“I am . . .”

“I . . .”

“I . . .”

And a single voice says calmly, simply, “What if you’re not?”

“ . . .”

“That’s all for now,” Roberta tells the jabbering crowd. “Thank you for coming.”

• • •

He cries, unable to stop. He doesn’t know where he is, where Roberta has brought him to. He is nowhere. There is no one in the world but the two of them.

“Shhh,” she tells him, gently rocking him back and forth. “It’s all right. Everything will be all right.”

But it does nothing to calm him. He wants to make the memory of those judgmental faces go away. Can she cut it out of his mind? Replace the memory with some random thoughts of another random Unwind? Can they do that for him? Can they please?

“This was just a first salvo from a world that still needs to process you,” Roberta says. “The next one will go better.”

Next one? How could he even survive a next one?

“Caboose!” he says. “Closed cover. Credits roll.”

“No,” Roberta tells him, holding him even more tightly. “It’s not the end, this is just the beginning, and I know you’ll rise to meet the challenge. You just need a thicker skin.”

“Then graft me one!”

She chuckles like it’s a joke, and her laughing makes him laugh too, which makes her laugh only louder, and suddenly in the midst of his tears he finds himself in a fit of laughter, yet angry at himself for it. He doesn’t even know why he’s laughing, but he can’t stop, any more than he could stop crying. Finally he gets himself under control. He’s exhausted. All he wants to do is sleep. It will be that way for him for a long time.

PUBLIC SERVICE ANNOUNCEMENT

“Have you ever stopped to think about all the people helped by Unwinding? Not just the recipients of much-needed tissues, but the thousands employed in the medical profession and supporting industries. The children, the husbands and wives of people whose lives are saved by grafts and transplants. How about soldiers wounded in the field of duty, healed and restored by the precious parts they receive? Think about it. We all know someone who has been positively touched by unwinding. But now the so-called Anti-Divisional Resistance threatens our health, our safety, our jobs, and our economy by disregarding a federal law that took a long and painful war to achieve.

“Write to your congressperson today. Tell your legislators what you think. Demand that they stand up against the ADR. Let’s keep our nation and our world on the right path.

“Unwinding. It’s not just good medicine, it’s the right idea.”

–Paid for by the Consortium of Concerned Taxpayers

Cam is in full mental and emotional regression. All kinds of theories for his backward slide are postulated and debated. Perhaps his rewound parts are rejecting one another. Perhaps his new neural connections are overloaded with conflicting information and have begun to collapse. The fact of it is that he has simply stopped talking, stopped performing for them—he’s even stopped eating and is now on an IV.

All nature of tests have been done on him, but Cam knows the tests will show nothing, because they can’t probe his mind. They can’t quantify his will to live—or lack of will.

Roberta paces in his bedroom. At first she showed great concern, but over the past few weeks, her concern has mildewed into frustration and anger.

“Do you think I don’t know what you’re doing?”

He responds by tugging his IV out of his arm.

Roberta comes to him quickly and reconnects it. “You’re being a stubborn, obstinate child!”

“Socrates,” he tells her. “Hemlock! Bottoms up.”