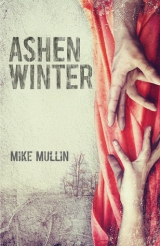

Текст книги "Ashen Winter"

Автор книги: Mike Mullin

Жанры:

Научная фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 4 (всего у книги 26 страниц)

Chapter 9

Dr. McCarthy returned to the office early the next morning. He poked his head into the exam room, letting in a sliver of light. “You guys up?”

I groaned. I’d barely slept. “I am now.”

“Bring your breakfast into the office so we don’t have to light another lantern, would you?”

“Sure.” I rolled out from under the blankets and groped for my coat. Darla was already up.

Dr. McCarthy stepped into the room and raised the lantern. Darla grabbed a couple packages of ham from our pack, and I picked up our toothbrushes and the pail of washwater. A crust of ice had formed on it overnight. All three of us trooped into the hall.

“I’ve got to check on the patient,” Dr. McCarthy said.

Darla and I waited in the dark hallway while the doctor checked on Ralph. It took less than five minutes. “How is he?” I asked as Dr. McCarthy emerged.

“Unconscious. Pulse and breathing are okay, but he’s running a fever.”

“You think he’ll wake up today?”

“No way to tell.”

As we were eating breakfast, the mayor of Warren, Bob Petty, joined us. He was the only person I knew who’d retained his pre-volcano roundness—in his face, belly, and stentorian baritone voice. “Heard you’ve got a bandit here, Jim.”

“They brought him in.” Dr. McCarthy tilted his head at Darla and me.

“You catch him out at your uncle’s farm?”

“Sort of,” Darla said. “We killed two of them. One got away.”

“We can’t have his type here. I’ll send the sheriff to escort him out.”

“You will not,” Dr. McCarthy said emphatically. “Bandit or not, he’s a patient. And he’s unconscious, hardly a threat.”

“Folks are worried.”

Dr. McCarthy stared at the mayor until the silence got uncomfortable.

The mayor cleared his throat. “Well, he wakes up, you fetch me or the sheriff. We’ll talk about it then.”

Dr. McCarthy changed the subject, asking about the latest news. The mayor had traded some pork for a handcranked battery charger and an emergency radio, which they were using to monitor the few shortwave stations still transmitting. Rumors and speculation abounded: The Chinese had annexed California, Oregon, and Washington, bringing in troops under the guise of humanitarian assistance. Mexico had closed its borders and started shooting American refugees. U.S. forces stationed in Afghanistan had left and were now occupying farmland in Argentina. Texas had seceded, and religious fanatics in Florida were agitating to follow suit. Half of Congress and four Supreme Court justices had resigned en masse and threatened to set up an alternate government. Some of them had been arrested. Black Lake, the huge military subcontractor that ran the camp where Darla and I had been imprisoned last year, had opened offices inside the Pentagon and White House.

There was no way to know if any of the rumors were true, and it didn’t seem to matter much, anyway. The only news that mattered to me was news of my parents—and none of that came in over the shortwave.

Belinda came in just as the mayor was leaving. She smiled and shook his hand, but her eyes were wary. When we’d cleaned up from breakfast, Belinda put us to work organizing patient files. All the office staff had left, so the filing was way behind. Having us work with the records was a violation of HIPAA rules, Belinda said, but she didn’t sound particularly worried, and I wasn’t sure what she meant by HIPAA, anyway. Each patient had a folder with brightly colored tabs that slotted into one of the open bookcases around the office. One entire bookcase, packed with records, had been marked DECEASED.

After a while, I started looking inside the folders. I knew I wasn’t supposed to, but the work was tedious, and I was curious. Every file ended with a sheet of copier paper, neatly torn in half. They all had the same handwritten heading: CERTIFICATE OF DEATH. Under that in smaller letters it read, “Prepared by James H. McCarthy, M.D.”

Every sheet listed a time, date, and cause of death. The causes varied wildly: stroke, exposure, heart attack, periodontitis—whatever that was. Darla started looking in the files, too, and we called out causes of death as we worked: blunt trauma from a fall, chronic bronchitis aggravated by silicosis, pneumonia, renal failure.

Then I heard a soft slap as the file Darla was holding hit the counter. “Jesus H. Christ,” she whispered.

“What is it?” I asked, turning toward her.

She didn’t respond, just slid the file along the counter to me.

There were two death certificates stapled to the file. The top one was for Elsa Hayward. I’d never heard of her. Cause of death: hemorrhage during childbirth. I lifted it to read the second certificate. Jane Doe Hayward: suffocated in childbirth. A full sheet of paper protruded below the death certificates—Elsa had evidently been a patient of Dr. McCarthy’s for a long time and had a chart. The last entry on the chart read, “If she’d been born six months ago, I could have saved them both.” The last phrase was repeated, ground into the paper with such force that it had torn through twice. “I could have saved them both. My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?”

His scrawled signature was smeared, bleeding into the page. The paper rippled. I ran my finger across it, feeling it pop and crackle under my touch. Suddenly I realized what I was touching—dried tears. I pulled my hand away from the file and swallowed hard, deeply embarrassed, as if I’d opened a door and found Dr. McCarthy behind it, sobbing. I gently closed the file and set it in its place on the bookcase with the other records of the deceased. Darla hugged me, her eyes shining with unshed tears. After that, we quit opening the files.

After lunch we hauled water for the office on Bikezilla. Warren’s water system had failed shortly after the volcano erupted. So we filled jugs and pails from the nearest working well, about two blocks away. Well water never freezes, even in the hardest winter, although the pipes and handpumps can.

As I set one of the jugs on the counter, I must have winced, because Darla said, “How’s your side?”

“It’s fine,” I replied.

“Let me check it. I should change the bandage, anyway.”

“I’m fine. Let’s see what else Belinda wants us to do.”

“After I check your bandage.”

I sighed, sank into a chair, and started taking off clothing.

When Darla began removing the bandages from my side, I bit back a scream. I knew it would hurt—it had ever since I’d been shot, but not this badly. The three puncture wounds were swollen and oozing puss. Red streaks radiated from my side like cobwebs.

“Wait here,” Darla said.

Dr. McCarthy took one look at it and said, “Cellulitis manifesting as severe erythema.”

“Ery-what?” I asked.

“The puncture wounds are infected.”

“Can you treat it?” Darla asked.

“Yes . . .”

“But?” I asked.

Dr. McCarthy shook his head. “But nothing, just a sec,” he said and left the room. When he returned, he was carrying seven large white pills and a cup of water. “Take one now and one every day until they’re gone. Should take two a day, but I don’t have enough for that.”

There was writing on the pills, but I couldn’t make it out in the low light of the lantern. “What are they?”

“Cipro. Full-spectrum antibiotic.”

“That must have been hard to come by.” I took the glass of water and swallowed a pill, feeling the lump it made as it passed down my throat.

“There’s a guy in Galena dealing in it. I don’t know where he gets it—I suspect he has access to the government stockpile.”

“Why’d the government stockpile it?” Darla asked.

“It’s one of the best treatments for anthrax. The stockpile was a civil defense measure.”

“How much do you have left?” I asked.

“Six tablets.”

I picked up my jacket from the floor and pulled the bag of envelopes holding the kale seeds out of the inner pocket. I extracted two envelopes.

Darla glared at me.

“Use one of these to buy more Cipro,” I told Dr. McCarthy as I handed them over. “I don’t want anyone to go without because of me. I owe you one envelope for Ralph’s medical care.”

Dr. McCarthy carefully tucked the seeds into his coat, frowning. “Thank you. But I’m going to repay your generosity in about the worst way possible. I need to clean and debride those wounds.”

“Debride?” I asked.

“Cut the dead flesh away.”

“That’s not going to feel particularly pleasant, is it?”

“Nope. Probably be the worst pain you’ve ever felt. I’ve been out of anesthetics for months, and buying more just isn’t as important as antibiotics, fever-reducers, antiseptics, and the like.”

I didn’t trust my voice not to quaver, so I nodded.

“If you’re lucky, you’ll pass out. We can numb your side up a bit with snow.”

“I’ll get some,” Darla offered.

“Get the cleanest snow you can find,” Dr. McCarthy said. “Fill one of the small buckets from the supply room. I’ll sterilize my scalpels.”

While I waited for them to return, my mind wandered back to the last time I’d been in a hospital, before the volcano. I’d biked to taekwondo and forgotten my keys. Nobody was home when I got back, so instead of waiting, I tried to break into my own house. I pushed the lower sash of one of our old-style storm windows inward, and the upper sash fell, snapping my arm at the wrist.

I called Mom, and she hurried home from a PTO board meeting to take me to the hospital. She prowled the waiting room like a caged animal, pacing until we were finally taken to an exam room. There she quizzed everyone who came near us about the best treatments for broken bones, the advantages of a sling versus a cast, and how to spot infection. Pretty soon, all the nurses were avoiding us.

When we finally got home, Dad glanced at my brand-new cast, said, “Looks good,” and turned back to his movie. My parents. They drove me crazy, but I still missed them desperately.

Darla returned to the exam room. I lay on my side on the hard metal table and bit down on Dr. McCarthy’s leather-wrapped stick. Darla packed snow over my wounds. She left the snow there until my side felt frozen and totally numb. But it wasn’t. Darla sat on my legs to keep me steady, but when Dr. McCarthy started carving on my side, I bucked so hard she nearly fell off.

I hoped, wished—prayed, even—that I’d pass out. No luck. I heard a muffled trumpeting sound and was puzzled for a moment before I realized it was me, screaming around the stick clamped in my teeth. Some blood started to trickle from my side onto the table. I focused on the blood, watching it spread into a small, irregular pool.

“The bleeding’s good,” Dr. McCarthy said. “Helps clean out the wound.”

“Uh,” I moaned around the stick.

“Almost done . . . there.”

Darla reached up and took hold of the stick. I couldn’t unclamp my teeth from it.

“Leave it there for now,” Dr. McCarthy said. “We’ll let the punctures bleed for a bit, then I’ll clean and bandage them. He’ll need the stick for that. I’m going to get fresh water and antiseptic.” He left the room.

“Can I let go of your legs for a minute?” Darla asked me.

I nodded weakly.

Darla pulled her sleeve over her hand and used it to wipe the tears from my face. Until then, I hadn’t even been aware I’d been crying. “You’re a tough guy, you know?”

“Uh,” I moaned.

Darla gently wrapped her arms around my shoulders and pressed herself against me. She softly kissed my eyelids, right then left. “Love you,” she whispered.

“’Uv ’ou ’oo,” I grunted back.

Dr. McCarthy came back into the room carrying a basin of water and two small bottles. “I leave for thirty seconds, and you’re making out in my operating room? Teenagers.”

Darla quit hugging me and glared at him, but he ignored her as he prepared to wash my wounds. I caught the hint of a smile peeking out of the corner of his mouth.

Washing and rebandaging the wounds didn’t hurt as badly as the cutting had, but there were still fresh tears for Darla to wipe away. It took a couple of minutes for me to relax enough to release the stick from between my teeth.

A wave of exhaustion washed over me. It was late afternoon, nowhere near bedtime, but I was suddenly so tired that I could barely sit upright. I stumbled to my feet. Darla grabbed my arm, concern plain on her face.

“I’m okay. Just tired.” I didn’t want her to worry.

She helped me down the hall to the exam room we’d slept in the night before, and I stretched out on the cot. My last thought before I drifted into unconsciousness: Why couldn’t I have passed out half an hour earlier?

Chapter 10

Darla’s snoring woke me. She didn’t snore all the time, but when she did, she sounded like a hibernating grizzly.

She’d left an oil lamp burning as a nightlight. I watched her sleep for a while as she lay curled up on the exam table. Her face was gorgeous, golden in the lamplight, although the effect was ruined by the flutter her nostrils made with each rip-roaring snore.

I thought about waking her—sometimes a gentle shake would be enough to end her snoring. But we’d both had a long day yesterday. And my side hurt badly enough that I didn’t think I could get back to sleep, anyway.

I rolled out of bed. I was dressed, but my boots were propped upright beside the cot. Darla must have taken them off me. I slipped on my boots, picked up the lantern, and went to peek out the back door of the clinic. It was pitch black and bitterly cold outside—still sometime in the middle of the night.

I closed the door and went back down the hall to the room the bandit occupied. He was curled on his left side under three blankets. Most of his face was hidden, covered by long hair and a scraggly beard. The one eye I could see was open, shining in the lamplight as he stared at me.

“You ready to talk?” I asked.

He tried to say something but started coughing instead. He hacked a huge wad of greenish phlegm onto the sheet. “Need to pee something fierce,” he said finally.

I sighed. “Bathroom doesn’t work. You want to go to the pit toilet outside or use a bedpan?”

“Try to get up, I guess.”

“Okay.” I grabbed a rag from the desk and tossed it at him. “Wipe up your mess first so you don’t smear it everywhere.”

He dabbed feebly at the phlegm, then dropped the rag on the floor. I scowled at him, picked up a clean corner of the rag with two fingers and tossed it into the laundry bin. He started to push himself upright, got to about forty-five degrees, and cried out. He grabbed his right side and collapsed back into the bed. When he regained his breath, he said, “Better use the bedpan.”

“Tell me when you’re done,” I said when I returned with it. “I’ll wait in the hall.” I left the door cracked so I’d hear if he tried to get out of the bed.

It seemed like a long wait. I remembered having to use a bedpan while I was staying at Darla’s house after I’d been injured by Target the year before. Actually, what I used was her mother’s second-best bread pan. We never did tell her mother about that. The memory of Mrs. Edmunds sat heavy in my chest. I’d known her for less than three weeks before she was murdered, but still, I missed her.

I’d be dead now if not for her. She’d shown me a kindness I could never repay—a kindness that moved her to welcome a bleeding stranger into her home.

“Done,” I heard from the exam room.

I went inside and took the bedpan from the bandit. It sloshed with urine so dark it was almost orange. I carefully set the stinking pan on the desk and lowered myself into a chair. “So, Ralph, you got that—”

“Ralph? Who’s Ralph?”

“You said your name is Ralph.”

“I did? When?”

“Last night.”

“Don’t remember that. No, I’m Ed. My dog’s name was Ralph.”

“Huh, wonder why you told me your name was Ralph?”

He twisted his head and stared at the ceiling.

“I need to know where you got that shotgun,” I said. “Blue Betsy, remember?”

“Why am I here?”

“Because I need to know where the shotgun came from.” This was getting old. “Trust me, I’d have preferred to leave you where you were. You’d have bled out or frozen to death.”

“Might’ve been better if you had.”

“Yeah. But—”

“You want to know where we got that shotgun. You going to kill me after I tell you?”

“What? No.”

“You’re just going to let me go. Tell me another one, kid. How do they do it here? Hanging? Or a bullet in the brain?”

“Neither. You’ve just got to move on and never come back.”

“Huh.” Ed folded his arms and closed his eyes.

“Where’d that shotgun come from?”

Ed was silent.

I leaned forward and breathed out heavily, staring at him. I had to convince him to trust me, at least a little. “You hungry?”

“Yeah, but you ain’t gonna feed me. Nobody’s got enough food to waste it on half-dead strangers.”

“Wait here.”

He laughed a wheezy, halfhearted cackle. “I can’t even sit up by myself.”

He had a point. I returned to the room Darla and I shared. She was still loudly asleep. I dug through our supplies, pulling out packages of food. I thought about what would impress Ed, but while we had plenty of food, there wasn’t much variety. I settled on a sandwich—two cornmeal pancakes for the bread with a slice of ham and a slab of goat cheese for the filling. Ice crystals shattered off the ham as I cut it, and the slice was hard as a board. We had no way to keep it warm. The cheese crumbled. As a finishing touch I peeled an icy kale leaf off the stack and added that to the sandwich.

Ed was staring at the door when I returned to his room. I put the sandwich in his hands.

“That’s . . . for me?” he asked.

“Yeah,” I replied, “Don’t eat too fast. You’ll barf.”

“I know.”

I sat him up, propped against the wall. He took a bite, chewing slowly. He held the sandwich in front of him as he ate, staring at it like a kid with a new iPhone on Christmas morning. Well, like a kid would have stared at an iPhone before the volcano. Now that kid would just toss the useless chunk of metal and glass aside and look for the good stuff: food, clothing, matches, or weapons.

I refilled his water cup.

Ed set the water beside him and said, “So this is corn, lettuce—”

“Kale,” I said.

“Kale, okay. Cheese and a slab of?”

“Ham.” I was quiet for a while as Ed ate. “Why’d your buddy leave you in that house, anyway?”

“I was slowing him down. I think he was going to put me out of my misery, but I got him to leave me there the same way I got you to back off. Pure D bluff. Told him I had one bullet left for the MAC-10. He didn’t want to find out the hard way whether I was telling the truth or not.”

“Took balls—so what did you do before the eruption?”

“Before the eruption?”

“Yeah, like, I went to high school. Cedar Falls High.”

“I . . .” Ed lifted the sandwich, staring at it, not eating it. “Mandy used to love ham sandwiches.”

“Mandy?”

“I haven’t thought about her in months. She was my life—how could I forget?”

“What about—”

“I guess you just go along, don’t you—”

“I don’t—”

“Every day you do what it takes to survive. And every day what you’re willing to do gets a little worse. Until you’re—Jesus, we were shooting kids.”

I tried to break in to ask about the shotgun again, but his voice dropped to a whisper and he kept talking. “Dear God, what have I done? What have I become?”

He buried his face in his hands and started crying huge, racking sobs that traveled in lurching waves down his belly. I was afraid he’d tear his wounds open, he was crying so hard. Tears leaked from between his fingers. I watched him, torn between disgust and an irrational desire to comfort the bandit who had attacked our farm, who would have killed Max and kidnapped Rebecca and Anna if he could have.

It took a while for Ed’s sobbing to subside to sniffles. “I was a bookkeeper,” he said at last. “I ran Peachtree for a machine shop in Ely. What happened to us? What happened to me?”

“What did happen to you?” I must have let some of the scorn I felt color my voice. He pulled his hands from his face and stared at me with an expression of such naked torment that I forgot to ask him again about the shotgun.

“It started with Ralph,” Ed said. “He was our dog. We were starving to death, Mandy and me.”

“I need—”

“Then a couple weeks later Mandy died anyway. Flu bug or maybe just the diarrhea. I should have just lain down to die next to her instead of burying her. A lot of people did, you know? I’d find them all over Ely, frozen together in their beds. The guys I ran with later laughed at them. But they did the right thing—instead of doing something just a little worse every day, all in the name of survival, shaving yourself away until the last sliver of who you were is gone.”

I raised my voice, trying to break in. “Would you let me—”

“I still dream about him. Ralph. He was a good dog.” Ed looked at me, his eyes stripped of color by the low light and his tears. “They say you are what you eat, you know? Sometimes in my dreams I’m Ralph, my tail thumping the floor, just happy to see Ed come home. Sometimes in my dreams I’m a pile of bones. Endless bones, burnt and cracked, feeding a greasy fire.” He turned his head and started crying again, softly this time.

I watched him cry for a moment. “I need to know where that shotgun came from,” I said for the eight millionth time.

“How did I—”

“Goddamn it, Ed! Tell me where my parents are!” Without thinking about it I’d taken a step toward him and raised my fists to my chin, planting my feet at a forty-five-degree angle: a fighting stance.

“I want to stay. In Warren. Rejoin civilization. And I want a pardon.”

“No freaking way am I letting a guy who tried to kidnap my sister and cousin stay within a hundred miles of Warren. The mayor was ready to throw you out while you were unconscious. Dr. McCarthy saved your ass. You tell me about that shotgun, and I’ll try to convince them to let you stay until you’re healthy enough to leave. Then you’ll get the hell out. In fact, you’ll get out of the whole state of Illinois.”

“I’m not saying anything then.”

“I could beat it out of you.” I raised my fists again.

“Go ahead,” Ed’s voice sounded hollow. “I don’t want to rejoin the gang, and if I leave on my own, I’m dead anyway. You may as well beat me to death. Wouldn’t take much right now.”

Ed’s eyes were brimming with tears again. I let out the breath I’d been holding, and with it my whole body deflated. I couldn’t beat on a defenseless man, no matter what he’d done. “You have to buy your way into Warren,” I said. “They aren’t taking just anybody—they don’t have enough food to do that. You’ve got to bring skills or supplies they need. You’ve got nothing to offer—the only thing Warren needs even less than bookkeepers are lawyers.”

“So you buy me a spot. Or convince your mayor to give me one.”

“They don’t want a bandit hanging around.”

“That’s your problem—if you still want to know about that shotgun.”

Gah! It was frustrating to admit it to myself, but he was right—he was half-dead, but he still had the upper hand. And I didn’t want to argue with him all night. I reached into my coat pocket and extracted an envelope. “There are 200 kale seeds in here. More than enough to buy you admission to Warren—if you can buy it at all. I’m not going to hang around here and try to convince the mayor and sheriff that you’re an okay guy. I’m not even sure you are. So here’s the deal—you tell me everything you know, and I give you the seeds. Trading them for admission to Warren is your problem, not mine.”

“How do I know the seeds are any good?”

“Goddammit—!”

“Okay, okay. I’ll take it.”

I handed him the envelope. “Talk.”

“Danny, he—”

“Who’s Danny? You said the gun was Bill’s.”

“Danny’s the leader of the gang I run with. Ran with, I mean. The Peckerwoods. Bill’s just the guy Danny gave the shotgun to.”

“Peckerwood? Isn’t that some kind of insult?”

“Yeah, I guess. It’s also the name of a racist gang in Anamosa, in the state prison. I mean, I was never there, but that’s where the leaders were when the volcano blew. Anyway, it started to get hard to find weapons and ammo. So Danny made a deal with some guards at one of the FEMA camps in Iowa. He got all kinds of weapons from them. Ammo, too. Most of the guns weren’t military stuff, so I figure they were confiscated from refugees.”

“So maybe my dad is at that FEMA camp? Where is it?”

“Might be, yeah. It’s outside Maquoketa.”

“Where’s that?”

“About halfway between Dubuque and the Quad Cities.”

That made it somewhere southwest of Warren. I wasn’t sure exactly. “So Danny was trading for the guns? What was he trading?”

“I don’t know for sure. Drugs, maybe. We had all the good stuff. Antibiotics, painkillers, aspirin. Danny had a source in Iowa City, but he never took me along when he cut deals.” A pained look passed over Ed’s face, and he moved his right hand to his side.

“What else do you know?”

“Nothing. That’s it. I swear.”

I shook my head. Two hundred more kale seeds gone. And for what?

![Книга Legendary Moonlight Sculptor [Volume 1][Chapter 1-3] автора Nam Heesung](http://itexts.net/files/books/110/oblozhka-knigi-legendary-moonlight-sculptor-volume-1chapter-1-3-145409.jpg)