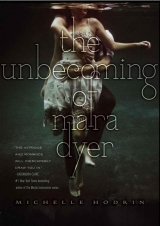

Текст книги "The Unbecoming of Mara Dyer"

Автор книги: Michelle Hodkin

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 2 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

“You have an anger-management problem.”

I whipped around at the sound of the warm, lilting British accent behind me.

The person it belonged to sat on the picnic table under the tiki hut. His general state of disarray was almost enough to distract me from his face. The boy—if he could be called that, looking like he belonged in college, not high school—wore Chucks with holes worn through, no laces. Slim charcoal pants and a white button-down shirt covered his lean, spare frame. His tie was loose, his cuffs were undone, and his blazer lay in a heap beside him as he lazily leaned back on the palms of his hands.

His strong jaw and chin were slightly scruffy, as though he hadn’t shaved in days, and his eyes looked gray in the shade. Strands of his dark chestnut hair stuck out every which way. Bedroom hair. He could be considered pale in comparison to everyone else I’d observed in Florida thus far, which is to say he wasn’t orange.

He was beautiful. And he was smiling at me.

5

SMILING AT ME LIKE HE KNEW ME. I TURNED my head, wondering if there was anyone behind me. Nope. No one there. When I glanced back in the boy’s direction, he was gone.

I blinked, disoriented, and bent to pick up my things. I heard footsteps approach, but they stopped just before they reached me.

The perfectly tanned blond girl wore heeled oxfords and white kneesocks with her just-above-the-knee charcoal and navy plaid skirt. The fact that I’d be wearing the same thing in a week hurt my soul.

She was linked arm-in-arm with a flawlessly groomed, startlingly enormous blond boy, and the two of them in their Croyden-crested blazers looked down their perfect noses with their perfect smattering of freckles at me.

“Watch it,” the girl said. With venom.

Watch what? I hadn’t done anything. But I decided not to say so, considering I knew exactly one person at the school, and we shared a last name.

“Sorry,” I said, even though I didn’t know what for. “I’m Mara Dyer. I’m new here.” Obviously.

A hollow smile crept over Vending Machine Girl’s puritanically pretty face. “Welcome,” she said, and the two of them walked away.

Funny. I did not feel welcome at all.

I shook off both strange encounters, and, map in hand, circled the building with no results. I climbed the stairs, and circled it again before finally finding my classroom.

The door was closed. I did not relish the idea of walking in late, or at all, really. But I’d already missed one class, and I was there, and the hell with it. I opened the door and stepped inside.

Cracks appeared in the classroom walls as twenty-something heads turned in my direction. The fissures spidered up, higher and higher, until the ceiling began to crumble. My throat went dry. No one said a word, even though dust filled the room, even though I thought I would choke.

Because it wasn’t happening to anyone else. Just to me.

A light crashed to the floor right in front of the teacher, sending a shower of sparks in my direction. Not real. But I tried to avoid them anyway, and fell.

I heard the sound of my face as it smacked against the polished linoleum floor. Then pain punched me between my eyes. Warm blood gushed out of my nostrils and swirled over my mouth and under my chin. My eyes were open, but I still couldn’t see through the gray dust. I could hear, though. There was a collective intake of breath from the class, and the sputtering teacher tried to determine just how hurt I was. Oddly, I did nothing but lie on the cool floor and ignore the muffled voices around me. I preferred my bubble of pain to the humiliation I would surely face upon standing.

“Umm, are you okay? Can you hear me?” The teacher’s voice grew increasingly panicky.

I tried to say my name, but I think it sounded more like “I’m dying” instead.

“Someone go get Nurse Lucas before she bleeds to death in my classroom.”

At that, I scrambled up, shifting woozily on alien feet. Nothing like the threat of nurses and their needles to get my ass into gear.

“I’m fine,” I announced, and looked around the room. Just a normal classroom. No dust. No cracks. “Really,” I said. “No need for the nurse. I just get nosebleeds sometimes.” Chuckle, chuckle. Laugh it off. “I don’t even feel anything. The bleeding’s stopped.” And it had, though I probably looked like a freak show.

The teacher eyed me warily before he answered. “Hmm. You really aren’t hurt, then? Would you like to go to the restroom to clean up? We can formally introduce ourselves upon your return.”

“Yeah, thanks,” I answered. “I’ll be right back.” I willed myself out of my dizziness, and snuck a glance at the teacher and my new classmates. Every face in the room registered a mixture of surprise and horror. Including, I noticed, Vending Machine Girl. Lovely.

I vacated the classroom. My body felt wiggly as I walked, like a loose tooth that could be dislodged by the slightest force. When I no longer heard the whispers or the teacher’s shaky voice, I almost broke into a run. I even missed the girls’ bathroom at first, barely registering the swinging door. I doubled back and, once inside, focused on the pattern of the hideous yolk-colored tile, counted the number of the stalls, did anything I could to avoid looking at myself in the mirror. I tried to calm myself, hoping to stave off the panic attack that would follow the sight of blood.

I breathed slowly. I did not want to clean myself up. I did not want to return to class. But the longer I was gone, the higher the likelihood that the teacher would send the nurse after me. I really didn’t want that, so I positioned myself in front of the wet counter, which was covered in wads of crumpled paper towels, and looked up.

The girl in the mirror smiled. But she wasn’t me.

6

IT WAS CLAIRE. HER RED HAIR SPILLED OVER MY shoulders where my brown hair should have been. Then her reflection bent, sinister in the glass. The room tilted, pitching me to the side. I bit my tongue, then braced my hands on the counter. When I looked up at the mirror, it was once again my face that stared back.

My heart pounded against my rib cage. It was nothing. Just like the classroom was nothing. I was okay. Nervous about my first day of school, maybe. My disastrous first day of school. But at least I was unsettled enough that my stomach forgot to churn at the sight of the drying blood on my skin.

I grabbed a handful of paper towels from the dispenser and wetted them. I brought them to my face to clean it up, but the pungent wet paper towel smell finally set my stomach roiling. I willed myself not to vomit.

I failed.

I had the presence of mind to pull back my long hair from my face as I emptied the meager contents of my stomach into the sink. At that moment, I was glad that the universe had thwarted my attempts at breakfast.

When I finished dry heaving, I wiped my mouth, gargled some water, and spit it into the sink. A thin film of sweat covered my skin, which had that unmistakable just-puked pallor. A charming first impression, to be sure. At least my T-shirt had escaped my bodily fluids.

I leaned on the sink. If I skipped the rest of Algebra, the teacher would just rustle up a mathlete posse to find me and make sure I hadn’t died. So I bravely headed out into the relentless heat and made my way back. The classroom door was still open; I’d forgotten to close it after my unceremonious departure, and I heard the teacher droning on about an equation. I took a deep breath and carefully walked in.

In seconds, the teacher was at my side. His thick glasses gave his eyes an insectlike quality. Creepy.

“Oh, you look much better! Please, have a seat right here. I’m Mr. Walsh, by the way. I didn’t catch your name before?”

“It’s Mara. Mara Dyer,” I said thickly.

“Well, Ms. Dyer, you certainly know how to make an entrance.”

The class’s low chuckle hovered in the air.

“Yeah, um, just clumsy, I guess.” I sat down in the first row, where Mr. Walsh had indicated, in an empty desk parallel to the teacher’s and closest to the door. Every seat in the row was unoccupied, except mine.

For eight painful minutes and twenty-seven infinite seconds, I sat sweltering in the seventh circle of my own personal inferno, motionless at my desk. I listened to the sound of the teacher’s voice but heard nothing. Shame drowned him out, and every pore of my skin felt painfully naked, open for exploitation by the pillaging eyes of my classmates.

I tried not to focus on the assault of whispers that I could hear but not decipher. I patted the back of my tingling head, as if the heat of the anonymous stares managed to burn through my hair, exposing my scalp. I looked desperately at the door, wishing to escape this nightmare, but I knew that the whispers would only spread as soon as I was outside.

The bell rang, marking the end of my first class at Croyden. A resounding success indeed.

I hung back from the mass exodus toward the door, knowing I’d need a book and a briefing on where the class was in the syllabus. Mr. Walsh told me ever so politely that I was expected to take the trimester exam in three weeks like everyone else, then returned to his desk to shuffle papers, and left me to face the rest of my morning.

It was blissfully uneventful. When lunch rolled around, I gathered my book-laden messenger bag and heaved it over my shoulder. I decided to look around for a quiet, secluded place to sit and read the book I’d brought with me. My vomiting shenanigans had ruined my appetite.

I hopped down the stairs two at a time, walked to the edge of the grounds, and stopped at the fence that bordered a large plot of undeveloped land. Trees towered above the school, casting one building entirely in shadow. The eerie screech of a bird punctured the breezeless air. I was in some preppy Jurassic Park nightmare, definitely. I violently opened my book to where I’d left off, but found myself reading and rereading the same paragraph before I gave up. That lump rose in my throat again. I slumped against the chain-link fence, the metal scoring marks in my flesh through the thin fabric of my shirt, and closed my eyes in defeat.

Someone laughed behind me.

My head snapped up as my blood froze. It was Jude’s laugh. Jude’s voice. I stood slowly and faced the fence, the jungle, as I hooked my fingers in the metal and searched for the source.

Nothing but trees. Of course. Because Jude was dead. Like Claire. And Rachel. Which meant that I’d had three hallucinations in less than three hours. Which wasn’t good.

I turned back to the campus. It was empty. I glanced at my watch and panic set in; only a minute to spare before my next class. I swallowed hard, grabbed my bag and rushed to the nearest building, but as I rounded the corner, I stopped cold.

Jude stood about forty feet away. I knew he couldn’t be there, that he wasn’t there, but he was there, unfriendly and unsmiling beneath the brim of the Patriots baseball cap he never took off. Looking like he wanted to talk.

I turned away and picked up my pace. I walked away from him, slowly at first, then ran. I glanced over my shoulder once, just to see if he was still there.

He was.

And he was close.

7

BY SOME STROKE OF LUCK, I FLUNG OPEN THE door to the closest classroom, 213, and it turned out to be Spanish. And judging by all of the taken desks, I was already late.

“Meez Dee-er?” the teacher boomed.

Distracted and disturbed, I pulled the door closed behind me. “It’s Dyer, actually.”

For my correction or for my lateness, I’ll never know, the teacher punished me, forced me to stand at the front of the room while she fired question after question at me, in Spanish, to which I could only respond, “I don’t know.” She didn’t even introduce herself; she just sat there, the muscles twitching in her veiny forearms as she scribbled self-importantly in her teacher book. The Spanish Inquisition took on a whole new meaning.

And it continued for a solid twenty minutes. When she finally stopped, she made me sit in the desk next to hers, in the front of the class, facing all of the other students. Brutal. My eyes were glued to the clock as I counted the seconds until it was over. When the bell rang, I bolted for the door.

“You look like you could use a hug,” said a voice from behind me. I turned around to face a smiling short boy wearing an open, white button-down shirt. A yellow T-shirt that said I AM A CLICHÉ was beneath it.

“That’s very generous of you,” I said, plastering a smile on my face. “But I think I’ll manage.” It was important to act not crazy.

“Oh, I wasn’t offering. Just making an observation.” The boy pushed his wild dreadlocks out of his eyes and held out his hand. “I’m Jamie Roth.”

“Mara Dyer,” I said, though he already knew.

“Wait, are you new here?” A mischievous grin reached his dark eyes.

I matched it. “Funny. You’re funny.”

He gave an exaggerated bow. “Don’t worry about Morales, by the way. She’s the world’s worst teacher.”

“So she’s that heinous to everyone?” I asked, after we were a safe distance away from the classroom. I scanned the campus for imagined dead people as I shifted my bag to my other shoulder. There were none. So far so good.

“Maybe not that heinous. But close. You’re lucky she didn’t throw any chalk at you, actually. How’s your nose, by the way?”

Had he been in Algebra II this morning?

“Better, thanks. You’re the first person to ask. Or say anything nice at all, actually.”

“So people have said not-nice things, then?”

I thought I glimpsed a flash of silver in his mouth when he spoke. A tongue stud? Interesting. He didn’t seem the type.

I nodded as my eyes drank in my new classmates. I knew there were variants of the school uniform—different shirt, blazer, and skirt/pants options, and sweater vests for the really adventurous. But when I looked for any telltale signs of cliques—wild shoes, or students with dyed black hair and makeup to match, I saw none. It was more than the uniforms; everyone somehow managed to look exactly alike. Perfectly groomed, perfectly well-behaved, not a hair out of place. Jamie, with his dreadlocks and tongue stud and exposed T-shirt, was one of the only standouts.

And, of course, the disheveled-looking person from this morning. I felt an elbow in my ribs.

“So, new chick? Who said what? Don’t leave a fella hangin’.”

I smiled. “There was this girl earlier who told me to ‘watch it.’” I described Vending Machine Girl to Jamie and watched his eyebrows rise. “The guy she was with was equally unfriendly,” I finished.

Jamie shook his head. “You went near Shaw, didn’t you?” Then he smiled to himself. “God, he really is something.”

“Uh … does this Shaw happen to have an overabundance of muscles and wear his shirt with a popped collar? He was on the arm of said girl.”

Jamie laughed. “That description could fit any number of Croyden douches, but definitely not Noah Shaw. Probably Davis, if I had to guess.”

I raised my eyebrows.

“Aiden Davis, lacrosse all-star and Project Runway aficionado. Pre-Shaw, he and Anna used to date. Until he came out of the metaphorical closet, and now they’re BFFs forevah.” Jamie batted his eyelashes. I kind of loved him.

“So what did you do to Anna?” he asked.

I gave him a look of mock horror. “What did I do to her?”

“Well, you did something to get her attention. You’d normally be beneath her notice, but the claws will come out if Shaw starts sniffing around you,” he said. He took a long look at me before he spoke again. “Which he will, having exhausted Croyden’s limited female resources already. Literally.”

“Well, she needn’t trouble herself.” I shuffled my schedule and my map, then looked around, trying to locate the annex for Biology. “I have no interest in stealing someone’s boyfriend,” I said. Or dating at all, I didn’t say, considering my last boyfriend was now dead.

“Oh, he’s not her boyfriend. Shaw dropped her ass last year after a couple of weeks. A record for him. Then she went even crazier—like the rest of them. Hell hath no fury like a woman scorned, and all that jazz. Anna used to be the abstinence poster girl, but post-Shaw, you could write a comic book about the many adventures of her vagina. It could wear a cape.”

I snorted. My eyes scanned the buildings in front of me. None of them looked like an annex. “And the guy she was all cozy with has no problem with this?” I asked, distracted.

Jamie quirked an eyebrow at me. “The Mean Queen? That would be no.”

Ah. “How’d he earn the nickname?”

Jamie looked at me like I was an idiot.

“I mean, specifically,” I said, trying not to be one.

“Let’s just say I tried to make friends with Davis once. In the platonic sense,” Jamie clarified. “I’m not his type. Anyway, my jaw still clicks when I yawn.” He demonstrated it for me.

“He hit you?”

The fountain burbled behind us as we crossed the quad, and stopped in front of the building farthest from the administration offices. I inspected the labels on the classroom doors. Completely random. I would never figure this place out.

“Indeed. Davis has a vicious right hook.”

We had that in common, apparently.

“I got him back later, though.”

“Oh?” Jamie wouldn’t stand a chance in a knife fight with Aiden Davis if all Aiden had was a roll of toilet paper.

Jamie smiled knowingly. “I threatened him with Ebola.”

I blinked.

“I don’t actually have Ebola. It’s a biosafety Level Four hot agent.”

I blinked again.

“In other words, impossible for teenagers to obtain, even if your father is a doctor.” He looked disappointed.

“Riiight,” I said, not moving.

“But Davis believed it and almost soiled himself. It was a defining moment for me. Until that rat bastard tattled to the guidance counselors. Who believed him. And called my dad, to verify I didn’t actually have Ebola at home. Idiots. One little joke involving hemorrhagic fever and they brand you ‘unstable.’ “He shook his head, then his mouth tilted into a smile. “You’re, like, totally freaked out right now.”

“No.” I was, just a tad. But who was I to be picky in the friend department?

He winked and nodded. “Sure. So what class do you have next?”

“Biology with Prieta? In the annex, wherever the hell that is.”

Jamie pointed to an enormous flowered bush about a thousand feet away. In the opposite direction. “Behind the bougainvillea.”

“Thanks,” I said, peering at it. “I never would have found it. So what’s your next class?”

He shrugged out of his blazer and button down. “AP Physics, normally, but I’m skipping it.”

AP Physics. Impressive. “So … are you in my grade?”

“I’m a junior,” Jamie said. He must have registered my skepticism because he quickly added, “I skipped a grade. Probably absorbed my parents’ short genes by osmosis.”

“Osmosis? Don’t you mean genetics?” I asked. “Not that you’re short.” A lie, but harmless.

“I’m adopted,” Jamie said. “And please. I’m short. No biggie.” Jamie shrugged, then tapped his watchless wrist. “You’d better get to Prieta’s class before you’re late.” He waved. “See ya.”

“Bye.”

And just like that, I made a friend. I mentally patted myself on the back; Daniel would be proud. Mom would be prouder. I planned to offer this news to her like a cat presenting a dead mouse to its owner. It might even be enough to help stave off therapy.

If, of course, I kept today’s hallucinations to myself.

8

I MANAGED TO SURVIVE THE REST OF THE DAY WITHOUT being hospitalized or committed, and, after school ended, Mom was waiting for me at the cul-de-sac exactly as Daniel said she would be. She excelled at those small “mom” moments, and didn’t disappoint today.

“Mara, honey! How was your first day?” Her voice bubbled with overenthusiasm. She pushed up her sunglasses over her hair and leaned in to give me a kiss. Then she stiffened. “What happened?”

“What?”

“You have blood on your neck.”

Damn. I thought I’d washed it all off.

“I had a nosebleed.” The truth, but not the whole truth, so help me.

My mother was quiet. Her eyes were narrowed, and full of concern. Par for the course, and so irritating.

“What?”

“You’ve never had a nosebleed in your life.”

I wanted to ask “How would you know?” but, unfortunately, she would know. Once upon a time I used to tell her everything. Those days were over.

I dug my heels in. “I had one today.”

“Out of nowhere? Randomly?” She gave me that piercing therapist stare, the one that says You’re full of it.

I wasn’t going to admit that I thought I saw my classroom fall apart the second I walked in it. Or that my dead friends reappeared today, courtesy of my PTSD. I’d been symptom-free since we’d moved. I went to my friends’ funerals. I packed up my room. I hung out with my brothers. I did everything I was supposed to do to avoid being Mom’s project. And what happened today wasn’t remotely worth what telling her would cost.

I looked her in the eye. “Randomly.” She still wasn’t buying it. “I’m telling you the truth,” I lied. “Can you leave me alone now?” But as soon as I spoke the words, I knew I’d regret them.

I was right. We drove the rest of the way home in silence, and the longer we went without speaking, the more obviously she stewed.

I tried to ignore her and focus on the route home, since I’d be driving myself to school in a few days thanks to Daniel’s long-overdue dentist appointment. It was only mildly comforting that Mr. Perfect had a penchant for cavities.

The houses we passed were all low-slung and blocky, with plastic dolphins and hideous Greek-style statues dotting their lawns. It was as if the city council convened and voted to manufacture Miami to be utterly devoid of charm. We passed generic strip mall after generic strip mall, all proclaiming Michaels! Kmart! Home Depot! with their collective might. I couldn’t for the life of me fathom why anyone would need more than one set of them within a fifty-mile radius.

We arrived at our new home after a gut-wrenching hour of traffic, which made my stomach roll with nausea for the second time that day. After pulling all the way into the driveway, my mother exited the car in a huff. I just sat there, motionless. My brothers weren’t home yet, my dad definitely wouldn’t be home yet, and I didn’t want to enter the lion’s den alone.

I stared at the dashboard, melodramatically stewing in the juices of my own bitterness, until a knock on the car door made me fly out of my skin.

I looked up and out at Daniel. The daylight had dwindled into evening, leaving the sky behind him a deep royal blue. Something inside me flipped. How long had I been sitting there?

Daniel peered at me through the open window. “Rough day?”

I tried to push my unease aside. “How’d you guess?”

Joseph slammed the door of Daniel’s Civic, then walked over with a huge smile on his face, his overstuffed backpack hooked between both arms. I got out of the car and clapped my little brother on the shoulder. “How was your first day?”

“Awesome! I made the soccer team and my teacher asked me to try out for the school play next week and there are some cool girls in my class but there’s also a really weird one who started talking to me but I was nice to her anyway.”

I grinned. Of course Joseph would sign up for every extracurricular activity. He was outgoing and talented. Both of my brothers were.

I compared the two of them, walking side-by-side toward the house with their matching gangly strides. Joseph looked more like our mother, and shared her stick-straight hair, unlike me and Daniel. But the two of them inherited her complexion, while I had my father’s Whitey McWhiterson skin. And there was no family stamp of similarity in our faces. It made me kind of sad.

Daniel opened the door to the house. When we moved here a month ago, I was surprised to discover that I actually liked it. Boxwood topiaries and flowers framed the gleaming front door, and the lot was huge. I remember my father saying that it was almost an acre.

But it wasn’t home.

The three of us entered together, a united front. I could hear my mother stalking in the kitchen but when she heard us come in, she appeared in the foyer.

“Boys!” she practically shouted. “How was your day?” She hugged them both, pointedly ignoring me while I hung back.

Joseph rehashed every detail with juvenile enthusiasm, and Daniel waited patiently for Mom to lob questions in his direction while he followed them to the kitchen. Seeing an opportunity for escape, I detoured down the long hallway that led to my bedroom, passing three sets of French doors on one side and several family photographs on the other. There were pictures of my brothers and me as infants and toddlers, and a few obligatory, awkward elementary school photos too. After that were pictures of other relatives and my grandparents. Today, one of them caught my eye.

An old black-and-white photograph of my grandmother on her wedding day stared back at me from its gilt frame. She was sitting placidly with her hennaed hands folded in her lap, her shining, jet-black hair parted severely in the middle. The flash in the photo made the bindi sparkle between her perfectly arched eyebrows, and she was swathed in extravagant fabric, the intricate patterns dancing on the edges of her sari. A strange sensation was there and gone before I could identify it.

Then Joseph came running down the hallway, two inches from knocking me over.

“Sorry!” he shouted, and raced around the corner. I tore my eyes from the picture and escaped into my new bedroom, closing the door behind me.

I plopped down onto my fluffy white comforter and pushed off my sneakers using my footboard. They fell to the carpet with a dull thud. I stared back at the dark, bare walls of my bedroom. My mother had wanted my room pink, like my old room; some psychological nonsense about anchoring me in the familiar. So stupid. A paint color wasn’t going to bring Rachel back. So I played the pity card and Mom let me choose an emo midnight blue instead. It made the room feel cool and my white furniture looked sophisticated in it. Small ceramic roses dripped from the arms of the chandelier my mother had installed, but against the dark walls, it didn’t overly feminize the room. It worked. And I had my own bathroom for the first time, which was a definite perk.

I hadn’t hung any sketches or pictures on the walls and didn’t plan to. The day before we left Rhode Island, I dismantled the quilt of photos and drawings I’d tacked up, saving a pencil sketch of Rachel’s profile for last. I stared at the solitary picture of her then, and marveled at how serious she looked. Especially compared to her giddy expression in school, the last time I remembered seeing her alive. I didn’t see what she looked like at the funeral.

It was closed-casket.