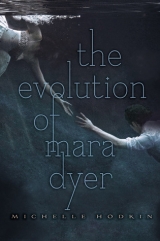

Текст книги "The Evolution of Mara Dyer"

Автор книги: Michelle Hodkin

Жанры:

Любовно-фантастические романы

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 6 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

16

BEFORE

Calcutta, India

I RESTED MY CHEEK AGAINST THE OPENING OF THE carriage and peeked out from behind the curtain at the creamy wax blossoms that sprouted from the trees and the thick green growth that clung to their trunks. Creepers hung from the branches above us, low enough for me to touch, but I did not care to. I knew that world, the green world of moss-covered rocks and glistening leaves, the jewel colored world of jungle flowers and sunsets. It no longer interested me. It was the tiny world of this carriage that was fascinating and new.

“Are you feeling ill?”

I heard the white man’s words, the question in them, but I did not understand their meaning. His voice was weak from deep within the carriage. I did not care to look at his face.

The carriage jerked, and my small fingers sank deep into the plush seat. Velvet, the man said when I first ran my fingers over it in wonder. I had never felt anything so soft; it did not exist in the world of fur and skin.

We moved at a slow pace, much slower than the elephants, and we crept forward relentlessly, for several days and nights. Eventually the wet forest gave way to dry earth and the green gave way to brown and black. The sharp smell of smoke filled the air, mingling with the scent of sandalwood in the carriage.

The horses slowed, and I peeked outside again. I was shocked by what I saw.

Huge, still beasts—larger than any I had ever seen—rose from the water. Their skinny trunks stretched up to the sky and they swarmed with men though they themselves did not move. There were noises I had never heard, foreign and strange. The taste of spices coated my tongue, and my nostrils filled with the scent of wet earth.

The white man reached up to point out at the large beasts. “Ships,” he said, and then dropped his trembling arm. His muscles were slack and weak, and he sank back into the shadows, his breathing heavy.

Then we stopped. The door to the carriage opened, and a kind-faced man in bright blue clothing held his arm out to me.

“Come,” he said to me, in a language I understood. His voice felt like sun-warmed water. I was not afraid of him, so I went. I waited for the white man to follow behind me as he had when we left the carriage on our journey, but he did not. He did shift toward the door, though his face was still in shadow. He held out a small black pouch to the man in blue, his arm shaking with the effort.

“Return here on the last day of each week and my clerk will fill it, so long as the girl is with you.”

The Man in Blue took the pouch and bowed his head. “The Raj is generous.”

The white man laughed. The sound was weak. “The East India Company is generous.” He beckoned me back to the carriage. I moved closer. The white man gestured for me to open my hand.

I did. He placed something cold and gleaming into it. I was repulsed by the dry texture of his skin.

“Let her buy something pretty,” he said to the Man in Blue.

“Yes, sir. What is her name?”

“I do not know. My guides have tried to coax her into telling, but she refuses to speak to them.”

“Does she understand?”

“She will nod or shake her head in response to questions asked in Hindi and Sanskrit, so I do believe so, yes. She has an intelligent eye. She will take to English quickly, I think.”

“She will make a lovely bride.”

The white man laughed, stronger this time. “I think my wife would take exception. No, the girl will be my ward.”

“When will you return for her?”

“I sail today for London, and business there will keep me occupied for at least six months. But I do hope to return soon after, perhaps with my wife and son.” The man coughed.

“Water?”

The white man’s coughs grew violent, but he waved his hand.

“Will you be well enough for the journey?”

The white man did not answer until his fit had ended. Then he said, “It is just the River Sickness. I need only clean water and rest.”

“Perhaps my wife could make a tincture for you before you go?”

“I shall be fine, thank you. I studied medicine after the Military Seminary at Croydon. Now then, I must be off. Do look after yourself, and her.”

The Man in Blue nodded, and the white man withdrew back into the darkness. The door of the carriage closed.

The Man in Blue walked to the front then, to the horses, and spoke to the man seated at the top in his own language. Ours.

“Make for him a mixture of dried garlic, lemon juice, honey, tamarind, and wild turmeric. Have him drink it four times each hour.” He then handed the man two shining circles from the black pouch. The coachman, the white man had called him. He nodded once and lifted the reins.

“Wait.” The Man in Blue held up his hand.

The coachman waited.

“Were you present when they found the girl?”

The coachman’s black eyes shifted to mine, then darted away. He shook his head slowly. “No. But my friend, a porter in their group, was.” He said nothing more but extended his hand to the Man in Blue, who sighed and placed two more silver discs on the coachman’s calloused palm.

The coachman smiled, revealing many missing teeth. His eyes flicked to mine. “I do not like her listening.”

The Man in Blue turned to me. “You may go explore,” he said, and urged me toward the ships.

Yes, I nodded, and pretended to leave. I made myself flat against the other side of the carriage instead. They could not see me. I waited and listened.

The Man in Blue spoke first. “What did you hear?”

The coachman’s voice was low. “They were hunting a tiger a few days’ journey from Prayaga. They followed it into the trees on the backs of their elephants, but without warning, the beasts stopped. Nothing could urge them forward—not sweets or sticks. This fool,” he said, tapping on the carriage, “insisted they continue on foot, but only three men would accompany him. One was a stranger—the white man’s guide, perhaps. Another was the cook. The last was a hunter, the brother of the porter, my friend.”

“Go on.”

“They followed the tracks of the animal into a sea of tall grass. All hunters know tall grass conceals death, and the brother, the hunter, wanted to turn back. The other man, the stranger, urged them forward, and the white man listened. The cook followed them, but the hunter refused and left alone. He was never seen again.”

“What happened?” The Man in Blue sounded curious, not afraid.

“The three men followed the tracks of the tiger for hours, until they vanished in a pool of blood.”

“From a recent kill?”

“No,” the coachman said. The horses stamped and snorted uneasily. “If it had been a tiger’s kill, there would have been tracks leading out of the pool of blood. There would have been bones and flesh, skin and hair. But there was nothing. No carcass. No hide. And no flies would touch it. They circled the pool and examined the grass. That was when they saw the footprints. A child’s footprints, soaked in blood.”

“And they led to this girl?”

“Yes,” the coachman said. “She was curled up in the roots of a tree, asleep. And in her fist was a human heart.”

17

MY EYES FLEW OPEN. THE VIVID COLORS OF MY nightmare were washed away by whiteness.

I was in bed, staring at a ceiling. But I wasn’t in my bed; I wasn’t at home. My skin was damp with sweat and my heart was racing. I reached for the dream, tried to catch it before it drifted away.

“How are you feeling?”

The last traces of it dissolved with the voice. I let out a slow breath and leaned up on stiff, creaky elbows to see who it belonged to. A man with a brown ponytail edged into my field of vision. I recognized him, but didn’t remember his name.

“Who are you?” I asked cautiously.

The man smiled. “I’m Patrick, and you fainted. How are you feeling?” he asked again.

I closed my eyes. I’m feeling sick of feeling sick. “Fine,” I said.

Dr. Kells appeared behind Patrick then. “You scared us, Mara. Do you have hypoglycemia?”

My thoughts were still slow but my heart was still racing. “What?”

“Hypoglycemia,” she repeated.

“I don’t think so.” I swung my legs over the side of the hard little bed. I shook my head but that only intensified the ache. “No.”

“Okay. The blood work will let us know for sure.”

“Blood work?”

She glanced at my arm. A piece of cotton was taped to the crook of my elbow; someone had taken off my hoodie and draped it over the foot of the cot. I pressed my hand against the sensitive skin there and tried not to look freaked out.

“It was an emergency. We were concerned about you,” Dr. Kells felt the need to explain. Which meant I apparently did look freaked out. “We called your mother—she sent your father here to pick you up early. I’m sure it’s nothing, but better safe than sorry.”

I stewed in silence until he arrived. He smiled widely when he saw me, but I could tell he was worried. He hunched down.

“How’re you feeling?”

Upset that they drew blood. Angry that I fainted. Scared it will happen again, because it happened before.

It happened before a flashback at the art exhibit Noah brought me to, and after a midnight hunt for my brother. It happened after I drank chicken blood in a Santeria shop that no longer seemed to exist. And each time I fainted, the borders of reality blurred, leaving me confused. Disoriented. Unsure of what was real. It made it hard to trust myself, and that was hard to bear.

But of course I couldn’t tell my father any of this, and he was waiting for an answer. So I just said, “They drew blood,” and left it at that.

“They were scared for you,” he said. “And it turns out your blood sugar was low. Want to go for ice cream on the way home?”

He looked so hopeful, so I nodded for his benefit.

He cracked a smile. “Fantastic,” he said, and helped me up off the cot. I swiped my hoodie and we moved toward the exit; I looked for Jamie on the way out but he was nowhere to be found.

My father leaned over a hutch by the front door and pulled out a thick-handled umbrella from a bin. “Cats and dogs out there,” he said, nodding through the glass. Sheets of rain battered the pavement and my dad struggled with the umbrella as he opened the door. I hugged my arms across my chest, staring out at the parking lot from our haven beneath the overhang. I wondered what time it was; the only other car in the lot besides my father’s was an old white pickup truck. The rest of the spaces were empty.

My dad made an apologetic face. “I think we’re going to have to make a run for it.”

“You sure you can run?”

He patted the spot beneath his rib cage. “Fit as a fiddle. Are you sure you can run?”

I nodded.

“Otherwise you can have the umbrella.”

“I’m good,” I said, staring into the rain.

“Okay. On the count of three. One,” he started, bending his front knee. “Two . . . Three!”

We dashed out into the deluge. My father tried to hold the umbrella over my head but it was pointless. By the time we threw open our respective car doors, we were soaked.

My dad shook his head, scattering droplets of rain onto the dashboard. He grinned, and it was infectious. Maybe ice cream was a good idea after all.

He started the car and began to pull out of the parking lot. Reflexively, I checked my refection in the side mirror.

My hair was plastered to my face, and I was pale. But I looked okay. Maybe a little thin. A little tired. But normal.

Then my reflection winked. Even though I hadn’t.

I pressed the heels of my palms into my eyes. I was seeing things because I was stressed. Afraid. It wasn’t real. I was fine.

I tried to make myself believe it. But when I opened my eyes, a light flashed in the mirror, blinding me.

Just headlights. Just headlights from the car behind us. I twisted in my seat to see, but the rain was so heavy that I couldn’t make out anything but the lights.

My father pulled out of the lot and onto the road, and the headlights followed us. Now I could see that they belonged to a truck. A white pickup truck.

The same one from the strip mall parking lot.

I shivered and huddled into my hoodie, then reached out and turned on the heat.

“Cold?”

I nodded.

“That New England blood is thinning out fast,” my father said with a smile.

I offered a weak one of my own in return.

“You okay, kid?”

No. I glanced into the fogged glass of the side mirror. The headlights still hovered behind us. I twisted around to see better through the rear window, but I couldn’t see who was driving.

The truck followed us onto the highway.

I felt sick. I wiped my clammy forehead with my forearm and squeezed my eyes shut. I had to ask. “Is that the same truck from the parking lot?” I tried not to sound paranoid, but I needed to know if he saw it too.

“Hmm?”

“Behind us.”

My father’s eyes flicked to the rearview mirror. “What parking lot?”

“At Horizons,” I said slowly, through clenched teeth. “The one we left ten minutes ago.”

“Dunno.” His eyes flicked back to the road. He obviously hadn’t noticed, and didn’t think it was a particularly big deal.

Maybe it wasn’t. Maybe the stress of the pictures, of the interview, triggered the fainting, which triggered my hallucination of a disobedient reflection in the mirror. Maybe the truck behind us was just an ordinary truck.

I checked the side mirror again. I could’ve sworn the headlights were closer.

Don’t think about it. I stared ahead at nothing in particular, listening to the hypnotic, mechanical swoop of the windshield wipers. My father was quiet. He reached to turn on the radio when we heard a squeal of tires.

Our heads jerked up as we were bathed in light. My father spun the steering wheel to the left as the pickup truck behind us swung into the right lane, nearly swiping the rear passenger side.

My father was yelling something. No, telling me something. But I couldn’t hear him because when the truck pulled up next to us, my mind blocked out everything but the sight of Jude behind the wheel.

I screamed for my father. He had to look. He had to see. But he was screaming too.

“Hold on!”

He’d lost control of the car. A black wave of panic threatened to pull me down with it as the car spun out beneath us on the rain-slick pavement. The truck cut across several lanes and raced ahead. My heart thundered against my rib cage and I gripped the center console with one hand. Bile rose in my throat—I was going to throw up. We were going to crash. Jude followed us and now we were going to crash—

The second I thought it, we were plunged into silence.

“Asshole!” my father yelled. I glanced over at him—sweat had beaded up on his forehead, the veins in his neck were corded.

That’s when I noticed we weren’t moving.

We weren’t moving.

We didn’t crash.

We sat motionless in the far left lane—the carpool lane. Cars veered around us and honked.

“No one knows how to drive in this goddamned city!” He slammed his fist on the dashboard and I jumped.

“I’m sorry,” he said quickly. “Mara—Mara?” His voice was brittle with worry. “Are you okay?”

I must have looked awful, because my father’s expression morphed from fury to panic. I nodded. I didn’t know if I could speak.

My father didn’t see him. He didn’t see Jude. I was the only one who had.

“Let’s get you home,” he muttered to himself. He started the car and we crawled the rest of the way. Even the retirees in their powder blue Buicks honked at us. Dad couldn’t have cared less.

We pulled into our empty driveway and he rushed to open my door, holding the umbrella above our heads. We hurried to the house, my father fumbling for his key before finally opening the front door.

“I’ll make some hot chocolate. Rain check on the ice cream?” he said, with a smile that didn’t reach his eyes. He was seriously worried.

I forced myself to speak. “Hot chocolate, yeah.” I rubbed my arms as a shudder of rain lashed the giant living room window, startling me.

“And I’ll turn off the air—it’s freezing in this house.”

A fake smile. “Thanks.”

He grabbed me then and hugged me so tightly I thought I might break. I managed to hug him back, and when we broke apart he headed for the kitchen and began to make a lot of noise.

I didn’t go anywhere. I just stood there in the foyer, rigid. I glanced up at the gilt mirror that hung above the antique walnut console table by the front door. My chest rose and fell rapidly. My nostrils were flared, my lips pale and bloodless.

I was seething. But not with fear.

With fury.

My father could’ve been hurt. Killed. And this time it wasn’t my fault.

It was Jude’s.

18

MINUTES OR SECONDS LATER, I PEELED MYSELF away from the mirror and marched to my room. But when I opened my bedroom door, I was highly disturbed to find eyes staring back at me.

A doll sat placidly on my desk, its cloth body leaning against a stack of my old schoolbooks. Her sewn-smile curved happily. Her black eyes were unseeing, but strangely focused in my direction.

It was my grandmother’s doll, my mother had told me when I was little. She had left it to me when I was just a baby, but I never played with it. I never named it. I didn’t even like it; the doll took up residence beneath a rotating assortment of other toys and stuffed animals in my toy chest, and as I grew up, it moved from the toy chest to a neglected corner of my closet, to be obscured by shoes and out-of-season clothes.

But now here she was, sitting on my desk. She didn’t move.

I blinked. Of course she didn’t move. She was a doll. Dolls don’t move.

But she had moved, though. Because the last time I saw her, she was packed away in a box, propped against stacks of old pictures and things from my room in Rhode Island. A box I hadn’t opened since—

Since the costume party.

I reached back to the memory of that night. I saw myself walk to my closet, preparing to slip off my grandmother’s emerald-green dress, only to find an opened cardboard box on my closet floor. I didn’t remember taking it down. I didn’t remember opening it up.

I rewound the memory. Watched myself walk backward out of the closet, watched my mother’s heels fit themselves back on my feet. Watched the water in the bathtub flow backward into the faucet—

The night I saw the doll was the night I was burned.

The skin prickled on the back of my neck. It had been a bad night for me. I was stressed about Anna and felt humiliated by Noah and I raced back even earlier, to when I first arrived home. I saw myself reach out to unlock the front door but—

It swung in before I touched it.

I thought I was hallucinating that night—and I had. I imagined my grandmother’s earrings at the bottom of the bathtub when they were in my ears the whole time. I assumed I forgot taking the box down from my closet too.

That was before I knew Jude was alive. If he was in my room last night, he could have been in my room that night.

My hands curled into fists. He took the box down from my closet. He opened it up.

And he wanted me to know it. That he was going through all my things. Watching me as I slept. Polluting my room. Polluting my house.

And when I left it, he chased my father and me back.

I was shivering before, but now I was feverishly hot. I felt out of control, and I couldn’t let my father see me like this—he was panicked enough. I bit back my anger and fear and shed my waterlogged clothes, then threw them in the sink. I turned on the shower and inhaled deeply as my bathroom filled with steam. I stepped into the hot water and let it course over my skin, willing my thoughts away with it.

It didn’t work.

I tried to remind myself that I wasn’t alone in this. That Noah believed me. That he was coming over later and when he did I would tell him everything.

I repeated the words on a loop, hoping they would calm me. I stayed in the shower until it ran cold. But when I emerged, I looked at my desk to find that the doll was no longer smiling.

It was leering.

My skin crawled as I stood there, wrapped in nothing but a towel, facing off with her as my heart beat wildly in my chest.

No, not her. It.

I snatched the doll off my desk. I walked to my closet and stuffed it back in one of my boxes. I knew, I knew the doll’s expression had not changed. My mind was playing tricks on me because I was stressed and panicked and angry, which was what Jude wanted.

I opened my desk drawer, ripped off a length of scotch tape, and taped the box shut, imprisoning the doll inside. No, not imprisoning. Packing. Packing the doll back inside. And then I dressed and made my way back to my father as if nothing had happened at all, because I had no other choice.

Time was supposed to heal all wounds, but how could it when Jude kept picking the scab?

It was early afternoon and Daniel, Joseph, and my mother had all come home. They talked loudly to one another as my father leaned against the pantry cabinets, holding a cracked mug with both hands.

“Mara!” My mother rushed over and wrapped me in a hug the second she noticed me.

Daniel set down his glass. Our eyes met over my mother’s shoulder.

“Thank God you’re okay,” she whispered. “Thank God.”

The hug lasted for an uncomfortably long time and when my mom released me, her eyes were wet. She quickly wiped the tears away and dove for the refrigerator. “What can I get you?”

“I’m okay,” I said.

“How about some toast?”

“I’m not so hungry.”

“Or cookies?” She held up a package of premade cookie dough.

“Yeah, cookies!” Joseph said.

Daniel made a face that I interpreted to mean: Say yes.

I forced a smile. “Cookies would be great.”

The second the words left my mouth, Joseph withdrew a cookie sheet from the drawer beneath the oven. Also the tinfoil. He grabbed the package of cookie dough from my mother and preheated the oven before she could get to it.

“How about some tea?” my mother asked, grasping for something, anything to do.

Daniel nodded his head yes, staring at me.

“I would love some,” I said, following his cue.

“I made hot chocolate,” my dad reminded her.

My mom rubbed her forehead. “Right.” She pulled out a mug from the glass-front cabinet and poured the contents of a saucepan into it, then handed it to me.

“Thanks, Mom.”

She tucked a strand of her short, straight hair behind her ear. “I’m so glad you’re okay.”

“Miami has the world’s worst drivers,” my father muttered.

My mother’s lips formed a thin line as she busied herself by making a pot of coffee. My eyes flicked to the kitchen window and searched our backyard through the rain.

I was searching for Jude, I realized with an accompanying sting of shame. He was making me paranoid. And I didn’t want to be.

“Hey, Mom?” I asked.

“Hmm?”

“Did you take out my doll?” There was a chance that she, not Jude, had moved it, and I had to be sure.

My mother looked up from the coffeepot, confused. “What doll?”

I exhaled through my nose. “The one I’ve had since I was a baby.”

“Oh, Grandma’s doll? No, honey. Haven’t seen it.”

That’s not what I’d asked, but I had my answer. She didn’t touch it. I knew who did, and this could not go on.

I glanced at the microwave clock, wondering when Noah would get here. I had to behave normally until he did.

“So how was Day One of spring break?” I asked Daniel between sips of hot chocolate. The liquid was warm, but didn’t warm me through.

“We went to the Miami Seaquarium.”

I almost choked. “What?”

Daniel shrugged a shoulder. “Joseph wanted to see the whale.”

“Lolita,” I said, setting down my drink.

My father shot my brother a look. “Wait, what?”

“It’s the name of the killer whale,” Daniel explained.

“How was it?” Mom asked.

Joseph shrugged. “Kind of sad.”

“How come?” Dad’s forehead creased.

“I felt bad for the animals.”

My turn. “Did Noah go with you?” I didn’t honestly care. I just wanted to know the answer to my real question without actually having to ask it or call him. Namely, where was he now, and was he coming back?

“Nope, but he’ll be over in an hour,” Daniel said. “Mom, can he stay for dinner?” He winked at me behind my mother’s back.

Thank you, Daniel.

“How come you ask her and not me?” my dad asked.

“Dad, can Noah stay for dinner?”

He cleared his throat. “Doesn’t his own family want to spend some time with him?”

Daniel made a face. “I don’t think so, actually.”

“Who wants cookies?” Mom asked. I caught the look she exchanged with my father as she opened the oven and the smell of heaven filled the kitchen.

My dad sighed. “It’s fine with me,” he said, and handed me his cell. “Go call him.”

I backed slowly out of the kitchen, then raced to my bedroom. I dialed Noah’s number.

“Hello?”

His voice was warm and rich and home and my eyes closed in relief at the sound of it. “Hi,” I said. “I’m supposed to tell you that you’re invited for dinner.”

“But . . .?”

“Something happened.” I kept my voice low. “How soon can you get here?”

“I’m getting in the car right now.”

“Noah?”

“Yes?”

“Plan to spend the night.”