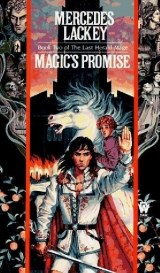

Текст книги "Magic's Promise"

Автор книги: Mercedes Lackey

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 6 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

He continued to make the appropriate noises at Roshya, and ignored the further stares of Jervis and Leren.

Mekeal had become so like Withen that Vanyel had to blink, seeing them together. Broad shoulders, brown beards trimmed identically, brown hair held back in identical tails with identical silver rings, dark brown eyes as open and readable as a dog's-dissimilar clothing was about all that differentiated them. That, and a few wrinkles in Withen's face, a few gray streaks in his hair and beard. Meke was perhaps a touch less muscular; not surprising since Withen's muscles had been built up in actual fighting during his career as a guard officer, and Meke had never seen any righting outside of an occasional skirmish with bandits. But otherwise – Withen did not look his age; with all the silver in his hair and the stress-lines around his eyes, Vanyel could be taken for older than his father.

Treesa, on the other hand, had not aged gracefully. She was still affecting the light, diaphanous gowns and pale colors appropriate to a young girl. Even if he had not been aware of the various cosmetic artifices employed by the ladies of Randale's Court, Vanyel would have known the coloring of her hair and cheeks to be false.

She's holding onto youth with teeth and nails, and it's still getting away from her, he thought sadly. Poor Mother. All she ever had to make her feel like she had some worth was being pretty and me, and she's losing both. Every year I become more of a stranger to her; every year her looks fade a little more. He glanced over at Roshya, who seemed to be doing her best to imitate Lady Treesa, and was relieved to see a gleam of lively good humor in her green eyes, and to hear a little of that sense of humor reflected in what she was saying. Treesa would likely become a bitter, unpleasant old woman on her own – but not with Roshya around.

The rest of Vanyel's brothers had become thinner, more reckless copies of Meke. They ate heavily and drank copiously and roared jokes at each other across the length of table, emphasizing points with a brandished fork. They’re probably terrors on the hunt – and I bet they hunt every other day. And probably fighting when they aren't hunting. They need something to keep them occupied, can't Father see that?

The more Vanyel saw, the uneasier he became. There was a restlessness in Withen's offspring that demanded an outlet, but there wasn't any. No wonder Meke is hoping for a Border-war, he realized as the meal drew to a close. This place is like a geyser just about to blow. And when it does, if there isn't any place for that energy to go, someone is going to get hurt. Or worse.

Servants began clearing the tables, and the adults rose and began to drift out on errands of their own. By Forst Reach tradition, the Great Hall belonged to the youngsters after dinner. Vanyel lingered until most of the others had gone out the double doors to the hallway; he was not in the mood to argue with anyone right now, or truly, even in the mood to make polite conversation. What he wanted was a quiet room, a little time to read, and more sleep.

It didn't seem as if the gods were paying much attention to his wants, lately.

Withen was waiting for him just beyond the doors.

“Son, about that horse-”

“Father, I keep telling you, Yfandes is not-”

Withen shook his head, an expression of marked impatience on his square face. “Not your Companion– Mekeal's horse. That damned stud he bought.”

“Oh.” Vanyel smiled sheepishly. “Sorry. Lately my mind stays in the same path unless you jerk its leash sideways. Tired, I guess.”

For the first time Withen actually looked at him, and his thick eyebrows rose in alarm. “Son, you look like hell.”

“I know,” Vanyel replied. “I've been told.”

“Bad?'' Withen gave him the same kind of sober attention he gave to his own contemporaries. Vanyel was obscurely flattered.

“Take all the horror stories coming north from the Karsite Border and double them. That's what it's been like.”

For once Withen's martial background was a blessing. He knew what Border-fighting was like, and his expression darkened for a moment. “Gods, son – that is not good to hear. So you'll be needing your rest. Well, I won't keep you too long, then – listen, let's take this out to the walk.”

The “walk” Withen referred to was a stone porch, rather like a low balcony and equipped with a balustrade, that ran the length of the north side of the building. Why Grandfather Joserlin had put it there, no one knew. It overlooked the gardens, but not usefully, most of the view being screened off by the row of cypresses he'd had planted just beneath the railing. It could be accessed by one door, through the linen storeroom. Not many people used it, unless they wanted to be alone.

Which actually made it a fine choice for a private discussion.

Blue, hazy dusk, scented with woodsmoke, was all that met them there. Vanyel went over to the balustrade and sat on the top of it, and Withen began again.

“About that horse – have you seen it?”

“I'm afraid so,” Vanyel replied. His window overlooked the meadows where the horses were turned loose to graze, and he'd seen the “Shin'a'in stud” kicking up his heels and attempting to impress Yfandes who was in the next field over. She had been ignoring him. “I hate to say this, Father, but Meke was robbed. I've seen a Shin'a'in warsteed; they're ugly, but not like that beast. They're smaller than that stud; they're not made to carry men in armor, they're bred to carry nomad horse-archers. They have very strong hindquarters, but their forequarters are just as strong, and they're a little short in the spine. 'Bunchy,' I guess you'd say. And their heads are large all out of proportion to the rest of them. The only thing a Shin'a'in warsteed has in common with Meke's nag is color. And besides, the only way an outsider could get a warsteed would be to steal a young, untrained one– and then kill the entire Clan he stole it from—and then kill the other Clans that came after him. No chance. Maybe somewhere there's Shin'a'in blood in that one, but it's cull blood if so."

Withen nodded. "I thought it might be something like that. I've seen their riding-beasts, the ones they will sell us. Beautiful creatures—so I knew that stud wasn't one of those, either. The animal is stupid, even for a horse, and that's going some. It's vicious, too—even with other horses; cut up the one mare Meke put it to before they could stop it. It's never been broken to ride, and I'm not sure it can be—and you know how I feel about that."

Vanyel half-smiled; one thing that Withen knew was his horses, and it was an iron-clad rule with him that all studs had to be broken for riding, the same as his geldings, and exercised regularly under saddle. No stud in his stable was allowed to laze about; when they weren't standing, they were working. It made them that much easier to handle at breeding-time. Most of Withen's own favorite mounts were his studs.

A mocker-bird shrilled in one of the cypresses, and Vanyel jumped at the unexpected sound. As he willed his heart to stop racing, Withen continued. "It hasn't taken a piece out of any of the stablehands yet, but I wonder if that isn't just lack of opportunity. And this is what Meke wants to breed half the hunter-mares to!"

Vanyel shook his head. Damn! I hope this jumping-at-shadows starts fading out. If I can't calm myself down, I'm going to hurt someone.

"I don't know what to tell you, Father. I'd have that beast gelded and put in front of a plow, frankly; I think that's likely all he's good for. Either that, or use the damned thing to train your more experienced young riders how to handle an unmanageable horse. But I'm a Herald, not a landholder; I have no experience with horsebreeding, and Meke is likely to point that out as soon as I open my mouth."

“But you have seen a real Shin'a'in warsteed,” Withen persisted.

“Once. With a real Shin'a'in on its-her-back. The nomad in question told me they don't allow the studs anywhere near the edge of the Dhorisha Plains. Only the mares 'go into the world' as he put it.” Even in the near dark and without using any Gift, Vanyel could tell his father was alive with curiosity. Valdemar saw the fabled Shin'a'in riding horses once in perhaps a generation and very few citizens of Valdemar had even seen the Shin'a'in themselves. Probably no one from Valdemar had ever seen a nomad on his warsteed until he had.

“Bodyguard, Father,” he said, answering the unspoken question. “The nomad was a bodyguard for one of their shamans, and I met them both in the k'Treva Vale. I doubt the shaman would have needed one, except that he must have been nearly eighty. I tell you, he was the toughest eighty-year-old I'd ever seen. He'd come to ask help from the Tayledras to get rid of some monster that had decided the Plains looked good and the horses tasty, and moved in.”

Withen shivered a little; talk of magic bothered him, and the fact that his son had actually been taught by the ghostly, legendary Hawkbrothers made him almost as uneasy as Vanyel's sexual inclinations.

The mocker-bird shrieked again, but this time Vanyel was able to keep from leaping out of his skin. “At any rate, I don't promise anything more except to try. But I want to warn you, I'm going to go at this the same way I'd handle a delicate negotiation. You won't see results at once, assuming I get any. Meke is as stubborn as that stud of his, and it's going to take some careful handling and a lot of carrots to get him to come around.”

Withen nodded. “Well, that's all I can ask. I certainly haven't gotten anywhere with him. And that's why I asked you to stick your nose into this. I'm no diplomat.”

Vanyel got up off the railing and headed for the door. “The fact is, Father, you and Meke are too damned much alike.”

Withen actually chuckled. “The fact is, son, you're too damned right.”

Vanyel slept until noon. The guest room was at the front of the building, well away from all the activity of the stables and yards. The bed curtains were as thick and dark as he could have wished. And someone had evidently given the servants orders to stay out of his room until he called for them. Which was just as well, since Van was trusting his reflexes not at all.

So he slept in peace, and rose in peace, and stood at the window overlooking the narrow road to the keep feeling as if he might actually succeed in putting himself back together if he could get a few more nights like the last one. A mere breath of breeze came in the window, and mocker – birds were singing-pleasantly, this time – all along the guttering above his head.

He could easily believe it to be still summer. He couldn't recall a gentler, warmer autumn.

He sent out a testing thought – tendril. :'Fandes?:

:Bright the day, sleepy one,: she responded, the Hawkbrother greeting.

He laughed silently, and took a deep breath of air that tasted only faintly of falling leaves and leafsmoke. :And wind to thy wings, sweeting. Would you rather laze about or go somewhere today?:

:Need you ask? Laze about, frankly. I think I'm going to spend the rest of the day the way I did this morning– napping in the sun, doing slow stretches. That pulled tendon needs favoring yet.:

He nodded, turning away from the window. :I don't doubt. Makes me glad I was running lighter than normal after you pulled it. :

She laughed, and moved farther out into her field so that he could see her from the window. :I won't say it didn't help. Well, go play gallant to your mother and get it over with. With any luck, she hasn't had a chance to bring in one of the local fillies.:

He grimaced, rang for a servant. One appeared with a promptness that suggested he'd been waiting right outside the door. Vanyel felt a pang of conscience, wondering how long he'd been out there.

“I'd like something to eat,” he said, “And wash water, please. And-listen, there is no reason to expect me to wake before midmoming, and noon is likelier. I surely won't want anyone or anything before noon. So pass that on, would you? No use in having one of you cool his heels for hours!”

The swarthy manservant looked surprised, then grinned and nodded before hurrying off after Vanyel's requests. Vanyel hunted up his clothing, deciding on an almost – new dark blue outfit about the time the wash water arrived. It felt rather strange not to be wearing Whites, but at the same time he was reveling in the feel of silk and velvet against his skin. The Field uniforms were strictly utilitarian, leather and raime, wool and linen. And he hadn't had many occasions to wear formal, richer Whites. No wonder they call me a peacock. Sensualist that I am – I like soft clothing. Well, why not?

The manservant showed up with food as Vanyel finished lacing up his tunic. He considered his reflection in the polished steel mirror, and ended up belting the tunic; it had fit perfectly when he'd last worn it, but now it looked ridiculously baggy without a belt.

He sighed, and applied himself to his breakfast. It was always far easier to gain weight than to lose it, anyway, that was one consolation!

After that he felt ready to face his mother. And whatever lady-traps she had baited and ready.

She always asked him to play whenever he stayed long enough, so he stripped the case from his lute and tuned it, then slung it on his back, and headed for her bower. Maybe he could distract her with music.

“Hello, Mother,” Vanyel said, leaning down to kiss Treesa's gracefully extended, perfumed fingertips. “You look younger every time I see you.”

The other ladies giggled, pretended to sew, fluttered fans. Treesa colored prettily at the compliment, and her silver eyes sparkled. For that moment the compliment wasn't a polite lie. “Vanyel, you have been away far too long!” She let her hand linger in his for a moment, and he gently squeezed it. She fluttered her eyelashes happily. Flirtation was Treesa's favorite game; courtly love her choice of pastime. It didn't matter that the courtier was her son; she had no intention of taking the game past the graceful and empty movements of the dance of words and gesture, and he knew it, and she knew he knew it, so everyone was happy. She was never so alive as when there was someone with her willing to play her game.

He fell in with the pretense, quite pleased that she hadn't immediately introduced anyone to him; that might mean she didn't have any girls she planned to fling at him. And she hadn't pouted at him either; so he was still in her good graces. He had much rather play courtier than have her rain tears and reproaches on his head for not spending more time with his family.

In the gauze-bedecked bower, full of fluttering femininity in pale colors and lace, he was quite aware that he looked all the more striking in his midnight blue. He hoped it would give him enough distinction-and draw enough attention to the silver in his hair – so that Treesa would remember he wasn't fifteen anymore. “Alas, first lady of my heart,” he said with a quirk of one eyebrow, “I fear I had very little choice in the matter. A Herald's duty lies at the King's behest.”

She dimpled, and patted the rose – velvet cushion of the stool placed beside her chair. “We've been hearing so many stories about you, Vanyel. This spring there was a minstrel here who sang songs about you!” She fussed with the folds of her saffron gown as he took his seat at her side. Her maids (those few who weren't at work at the three looms placed against the wall) and her fosterlings all gathered up their sewing and spinning at this unspoken signal and gathered closer. The sun-bright room glowed with the muted rainbow colors of their gowns, and Vanyel had to work to keep himself from smiling, as faces – young, and not-so-young, pretty and plain – turned toward him like so many flowers toward the sun. He'd not gotten this kind of attention even when he was the petted favorite of this very bower.

But then, when he'd been the bower pet, he'd only been a handsome fifteen-year-old, with a bit of talent at playing and singing. Now he was Herald-Mage Vanyel, the hero of songs.

:And all too likely to have his foot stepped on if he comes near me with a swelled head,: said Yfandes.

He bent his head over the lute and pretended to tune it until he could keep his face straight, then turned back to his mother.

“I know better songs than those, and far more suited to a lovely lady than tales of war and darkness.”

There was disappointment in some faces, but Treesa's eyes glowed. “Would you play a love song, Van?” she asked coquettishly. “Would you play 'My Lady's Eyes' forme?”

Probably the most inane piece of drivel ever written, he thought. But it has a lovely tune. Why not?

He bowed his head slightly. “My lady's wish is ever my decree,” he replied, and began the intricate introduction at once.

He couldn't help noticing Melenna sitting just behind a knot of three adolescents, her hands still, her eyes as dreamy as theirs. She was actually prettier now than she had been as a girl.

Poor Melenna. She never gives up. Almost fourteen years, and she's still yearning after me. Gods. What a mess she's made out of her life. He wondered somewhere at the back of his mind what had become of the bastard child she'd had by Mekeal, when pique at his refusing her had led her to Meke's bed. Was it a boy or girl? Was it one of the girls pressed closely around him now? Or had she lost it? Loose ends like that worried him. Loose ends had a habit of tripping you up when you least expected it, particularly when the loose ends were human.

He got the answer to his question a lot sooner than he'd guessed he would.

“Oh, Van, that was lovely,” Treesa sighed, then dimpled again. “You know, we haven't been entirely without Art and Music while you've been gone. I've managed to find myself another handsome little minstrel, haven't I, 'Lenna?”

Melenna glowed nearly the same faded-rose as her gown-one of Treesa's, remade; Vanyel definitely recollected it. “He's hardly as good as Vanyel was, milady,” she replied softly.

“Oh, I don't know,” Treesa retorted, with just a hint of maliciousness. “Medren, why don't you come out and let Vanyel judge for himself?”

A tall boy of about twelve with an old, battered lute of his own rose slowly from where he'd been sitting, hidden by Melenna, and came hesitantly to the center of the group. There was no doubt who his father was – he had Meke's lankiness, hair, and square chin, though he was smaller than Mekeal had been at that age, and his shoulders weren't as broad. There was no doubt either who his mother was – Melenna's wide hazel eyes stared at Vanyel from two faces.

The boy bobbed at Treesa. “I can't come close to those fingerings, milord, milady,” he said, with an honesty that felt painful to Vanyel.

“Some of that's the fact that I've had near twenty years of practice, Medren,” Vanyel replied, acutely aware that both Treesa and Melenna were eyeing him peculiarly. He was not entirely certain what was going on. “But there's some of it that's the instrument. This one has a very easy action – why don't you borrow it?”

They exchanged instruments; the boy's hands trembled as he took Vanyel's finely crafted lute. He touched the strings lightly, and swallowed hard. “What -” his voice cracked, and he tried again. “What would you like to hear, milord?”

Vanyel thought quickly; it had to be something that wouldn't be so easy as to be an insult, but certainly wouldn't involve the intricate fingerings he'd used on “My Lady's Eyes.”

“Do you know 'Windrider Unchained'?” he asked, finally.

The boy nodded, made one false start, then got the instrumental introduction through, and began singing the verse.

And Vanyel nearly dropped the boy's lute as the sheer power of Medren's singing washed over him.

His voice wasn't quite true on one or two notes; that didn't matter, time, maturity, and practice would take care of those little faults. His fingerings were sometimes uncertain; that didn't matter either. What mattered was that, while Medren sang, Vanyel lived the song.

The boy was Bardic Gifted, with a Gift of unusual power. And he was singing to a bowerful of empty-headed sweetly-scented marriage-bait, wasting a Gift that Vanyel, at fifteen, would willingly have sacrificed a leg to gain. Both legs. And counted the cost a small one.

It was several moments after the boy finished before Vanyel could bring himself to speak – and he really only managed to do so because he could see the hope in Medren's eyes slowly fading to disappointment.

In fact, the boy had handed him back his instrument and started to turn away before he got control of himself. “Medren – Medren!” he said insistently enough to make the boy turn back. “You are better than I was, even at fifteen. In a few years you are going to be better than I could ever hope to be if I practiced every hour of my life. You have the Bardic-Gift, lad, and that's something no amount of training will give.”

He would have said more – he wanted to say more – but Treesa interrupted with a demand that he sing again, and by the time he untangled himself from the concentration the song required, the boy was gone.

The boy was on his mind all through dinner. He finally asked Roshya about him, and Roshya, delighted at having actually gotten a question out of him, burbled on until the last course was removed. And the more Vanyel heard, the more he worried.

The boy was being given – at Treesa's insistence – the same education as the legitimate offspring. Which meant, in essence, that he was being educated for exactly nothing. Except – perhaps – one day becoming the squire of one of his legitimate cousins. Meanwhile his real talent was being neglected.

The problem gnawed at the back of Vanyel's thoughts all through dinner, and accompanied him back to his room. He lit a candle and placed it on the small writing desk, still pondering. It might have kept him sleepless all night, except that soon after he flung himself down in a chair, still feeling somewhat stunned by the boy and his Gift, there came a knock on his door.

“Come -” he said absently, assuming it was a servant.

The door opened. “Milord Herald?” said a tentative voice out of the darkness beyond his candle. “Could you spare a little time?”

Vanyel sat bolt upright. “Medren? Is that you?”

The boy shuffled into the candlelight, shutting the door behind him. He had the neck of his lute clutched in both hands. “I – ” His voice cracked again. “Milord, you said I was good. I taught myself, milord. They – when they opened up the back of the library, they found where you used to hide things. Nobody wanted the music and instruments but me. I'd been watching minstrels, and I figured out how to play them. Then Lady Treesa heard me, she got me this lute. ...”

The boy shuffled forward a few more steps, then stood uncertainly beside the table. Vanyel was trying to get his mind and mouth to work. That the boy was this good was amazing, but that he was entirely self-taught was miraculous. “Medren,” he said at last, “to say that you astonish me would be an understatement. What can I do for you? If it's in my power, it's yours.”

Medren flushed, but looked directly into Vanyel's eyes. “Milord Herald-”

“Medren,” Vanyel interrupted gently, “I am not 'Milord Herald,' not to you. You're my nephew; call me by my given name.”

Medren colored even more. “I-V – Vanyel, if you could – if you would – teach me? Please? I'll -” he coughed, and lowered his eyes, now turning a red so bright it was painful to look at. “I'll do anything you like. Just teach me.”

Vanyel had no doubt whatsoever what the boy thought he was offering in return for music lessons. The painful – and very potently sexual – embarrassment was all too plain to his Empathy. Gods, the poor child – Medren wasn't even a temptation. I may be shaych, but – not children. The thought's revolting.

“Medren,” he said very softly, “they warned you to stay away from me, didn't they? And they told you why.”

The boy shrugged. “They said you were shaych. Made all kinds of noises. But hell, you're a Herald, Heralds don't hurt people.”

“I'm shaych, yes,” Vanyel replied steadily. “But you – you aren't.''

“No,” the boy said. “But hell, like I said, I wasn't worried. What you could teach me – that's worth anything. And I haven't got much else to repay you with.” He finally looked back up into Vanyel's eyes. “Besides, there isn't anything you could do to me that'd be worse than Jervis beating on me once a day. And they all seem to think that's all right.”

Vanyel started. “Jervis? What – what do you mean, Jervis beating on you? Sit, Medren, please.”

“What I said,” the boy replied, gingerly pulling a straight-backed chair to him and taking a seat. “I get treated just like the rest of them. Same lessons. Only there's this little problem; I'm not true-born.” His tone became bitter. “With eight true-born heirs and more on the way, where does that leave me? Nowhere, that's where. And there's no use in currying favor with me, or being a little easy on me, 'cause I don't have a thing to offer anybody. So when time comes for an example, who gets picked? Medren. When we want a live set of pells to prove a point, who gets beat on? Medren. And what the hell do I have to expect at the end of it, when I'm of age? Squire to one of the true-born boys if I'm lucky, the door if I'm not. Unless I can somehow get good enough to be a minstrel.”

Vanyel's insides hurt as badly as if Medren had punched him there. Gods – His thoughts roiled with incoherent emotions. Gods, he's like I was – he's just like I was – only he doesn't have those thin little protections of rank and birth that I had. He doesn't have a Lissa watching out for him. And he has the Gift, the precious Gift. My gods -

“ 'Course, my mother figures there's another way out,” Medren continued, cynically. “Lady Treesa, she figures you've turned down so many girls, she figures she's got about one chance left to cure you. So she told my mother you were all hers, she could do whatever it took to get you. And if my mother could get you so far as to marry her, Lady Treesa swore she'd get Lord Withen to allow it. So my mother figures on getting into your breeches, then getting you to marry her – then to adopt me. She says she figures the last part is the easiest, 'cause she watched you watching me, and she knows how you feel about music and Bards and all. So she wanted me to help.”

Poor Melenna. She just can't seem to realize what she's laying herself open for. “So why are you telling me this?” Vanyel found his own voice sounding incredibly calm considering the pain of past memories, and the ache for this unchildlike child.

“I don't like traps,” Medren said defiantly. “I don't like seeing them being laid, I don't like seeing things in them, and I don't much like being part of the bait. And besides all that, you're – special. I don't want anything out of you that you've been tricked into giving.”

Vanyel rose, and held out his hand. Medren looked at it for a moment, and went a little pale despite his brave words. He looked up at Vanyel with his eyes wide. “You -you want to see my side of the bargain?” he asked tremulously.

Vanyel smiled. “No, little nephew,” he replied. “I'm going to take you to my father, and we're going to discuss your future.”

Withen had a room he called his “study,” though it was bare of anything like a book; a small, stone-walled room, windowless, furnished with comfortable, worn-out old chairs Treesa wouldn't allow in the rest of the keep. It was where he brought old cronies to sit beside the fire, drink, and trade tall tales; it was where he went after dinner to stare at the flames and nurse a last mug of ale. That's where Vanyel had expected to find him; and when Vanyel ushered Medren into the stuffy little room, he could tell by his father's stricken expression that Withen was assuming the absolute worst.

“Father,” he said, before Withen could even open his mouth, “do you know who this boy is?”

Candlelight flickered in his father's eyes as Withen looked at him as if he'd gone insane, but he answered the question. “That's – uh – Medren. Melenna's boy.”

“Melenna and Mekeal's, Father,” Vanyel said forcibly. “He's Ashkevron blood, and by that blood, we owe him. Now just how are we paying him? What future does he have?'' Withen started to answer, but Vanyel cut him off. “I'll tell you, Father. None. There are how many wedlock-born heirs here? And how much property? Forst Reach is big, but it isn't that big! Where does that leave the little tagalong bastard when there may not be enough places for the legitimate offspring? What's he going to do? Eke out the rest of his life as somebody's squire? What if he falls in love and wants to marry? What if he doesn't want to be somebody's squire all his life? You've given him the same education and the same wants as the rest of the boys, Father. The same expectations; the same needs. How do you plan on making him content to take a servant's place after being raised like one of the heirs?”

“I – uh – '

“Now I'll tell you something else,” Vanyel continued without giving him a chance to answer. “This young man is Bardic-Gifted. That Gift is as rare – and as valued in Valdemar – as the one that makes me a Herald. And we Ashkevrons are letting that rare and precious Gift rot here. Now what are we going to do about it?”

Withen just stared at him. Vanyel waited for him to assimilate what he'd been told. The fire crackled and popped beside him as Withen blinked with surprise. “Bardic-Gifted? Rare? I knew the boy played around with music, but – are you telling me the boy can make a future out of that?”

“I'll tell you more than that, Father. Medren will be a first-class Bard if he gets the training, and gets it now. A Full Bard, Father. Royalty will pour treasure at his feet to get him to sing for them. He could earn a noble rank, higher than yours. But only if he gets what he needs now. And I mean right now.”

“What?” Withen's brow wrinkled in puzzlement.