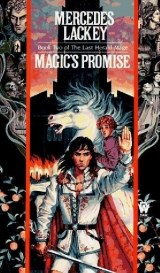

Текст книги "Magic's Promise"

Автор книги: Mercedes Lackey

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 13 (всего у книги 21 страниц)

“The o – the lady who was with you?” Now Vanyel picked up only respect, mixed with the good-natured contempt of the young for the old.

“Does she frighten you?” He half-smiled, stiffly. “She should, you know, she's a terrible tyrant!”

Tashir shook his head.

“How about Kylla? She's the baby who's always getting out of the nursery, usually without a stitch on. I expect she's done it at least once while I was sleeping. Does she bother you?”

Bewilderment. “She's kind of cute. Why should I be afraid of her?”

Vanyel worked his way up and down the age scale of all the women at Forst Reach that he thought the youngster might have seen. Only when he neared women between twenty and Treesa's age did he get any negative responses, and when he mentioned a particularly pretty fourteen-year-old niece, there was definite interest – and real attraction.

From time to time Vanyel dropped in questions about his feelings toward men; not just himself, but Jervis, Medren, some of the servants the youngster had encountered. And at no time, even as he began to relax, did Tashir evidence any attraction to men in general or Vanyel in particular – except, perhaps as a protector. Certainly not as a potential lover. Whenever that topic came up, the fear came back.

Finally Vanyel sighed, and took his hand away. It ached, ached as badly as the injured left did when it rained. He rubbed it, wishing he could massage away the ache in his own heart. “Tashir – let me say that I'm very flattered, but – no. I will not oblige you. Because you've come to me for all the wrong reasons. You aren't here because you know you're shay'a'chern; you aren't even here because you're attracted to me. You're here because women of a certain age frighten you. That's not enough to base a relationship on, not the kind you're asking me for. You don't know what you want; you only know what you don't want. ''

“But -” the youngster said, his eyes all pupil, “but you – when you were younger than me – Jervis said – “

Vanyel had to look away; he couldn't bear that gaze any more. “When I was younger than you I knew what I was, and I knew what I wanted, and who I wanted it with. You're looking for – for someone to like you, for someone to be close to. You're just grasping at something that looks like a solution, and you're hoping I'll make up your mind for you. And I could do that, you know. Even without using magic, I could probably convince you that you were shay'a'chern, at least for a little while. I could ... do things, say things to you, that would make you very infatuated with me.” He paused, and forced a breath into his tight chest, looking back down at Tashir 's bewildered eyes. “But that wouldn't solve your problems, it would only let you postpone finding a solution for a while. And I truly don't think that would help you in the least. Any answers you find, Tashir, are going to have to be answers you decide on for yourself. Here – “ He offered the youngster his hand. Tashir looked at it in surprise, then tentatively put his own hand in Vanyel's.

He looked even more surprised when Vanyel hauled him to his feet, put his palm between his shoulderblades, and shoved him gently toward and out the door. “Go to bed, Tashir,” Vanyel said, trying to make his tones as kindly as he could. “You go have another chat with Jervis. Go riding with Nerya. Try making some friends around the Reach. We'll talk about this later.”

And he shut the door on him, softly, but firmly.

He began to shake, then, and clung to the doorframe to keep himself standing erect. He leaned his forehead against the doorpanel for a long time before he stopped

trembling. When he thought he could walk without stumbling, he turned and went back to his chair, and sat down in it heavily.

He hurt. Oh, gods, he hurt. He felt so empty – and twice as alone as before. He stared at the candleflame while it burned down at least half an inch, trying to thaw the adamantine lump of frozen misery in his stomach, and having a resounding lack of success.

:You did the right thing, Chosen.: The bright voice in his mind was shaded with sympathy and approval both.

:I know I did,: he replied, around the ache. :What else could I do? Just – tell me, beloved – why can't I feel happy about it? Why does doing the right thing have to hurt so damned much?:

She had no answer for him, but then, he hadn't really expected one.

If I were just a little less ethical – and how much of that is because he looks like 'Lendel? Gods. It isn't just my heart that hurts. And I'm so damned lonely.

Eventually he slept.

It took a week before he felt anything like normal. Challenging Jervis when he had been straight out of his bed had been pure bluff. He wouldn't have been able to stand against the armsmaster for more than a few breaths at most. He wondered if Jervis had guessed that.

Arms practice was interesting. He and Jervis circled around each other, equally careful with words and blows. There was so much between them that was only half-healed, at best, that it was taking all his skill at diplomacy to keep the wounds from reopening. And no little of that was because it sometimes seemed that Jervis might be regretting his little confession.

But they were civil to each other, and working with each other, which was a damn sight more comfortable than being at war with each other.

“That boy's got more'n a few problems, Van,” Jervis said, leaning on his sword, and watching Tashir work out with Medren. The young man was being painstakingly careful with the younger boy, and he was wearing the first untroubled expression Vanyel had seen on his face.

And for once, there was no fear in him. For once, he was just another young man; a little more considerate of the smaller, younger boy than most, but still just another young man.

“I know,” Vanyel replied, shifting his weight from his right foot to his left. “And I know you aren't talking about fighting style.” He chewed his lip a little, and decided to ask the one question that would decide whether or not he was going to be able to carry out the plan he'd made in the sleepless hours of the last several nights. “Tell me, do you feel up to handling him by yourself for a bit? You'll have Savil in case he does anything magical again, though I don't think he will, but I don't think he'll open up to Savil the way he will to you.”

Jervis gave him a long look out of the corner of his eye. “And just where are you going to be?”

Vanyel looked straight ahead, but spoke in a low voice that was just loud enough for Jervis to hear him. The fewer who knew about this, the better. “Across the Border. All the answers to our questions are over there, including the biggest question of all – if Tashir didn't rip a castle full of people to palm-sized pieces, who did? And why?”

And away from him, maybe I can get my thinking straight.

Jervis considered his words, as the clack and thwack of wooden practice blades echoed up and down the salle. “How long do you think you'll be out over there? You're not going as yourself, I hope?”

“No.” He smiled wanly. A Herald was not going to be a popular person in Highjorune right now. “I've got a disguise that's been very useful in the past; Herald Vanyel is still going to be resting in the bosom of his family. The gentleman who's going to cross the Border is a rather scruffy minstrel named Valdir. Nobody notices a minstrel asking questions; they're supposed to. And since the only person who saw my face clearly is now on his way to Haven with a rock in his craw, I should be safe. I expect to take a fortnight at most.”

“Get that guard up, Medren! Huh. Sounds good to me. Gods know we aren't getting any answers out of the boy at the moment. What's Savil say?”

Vanyel winced as Medren got in a particularly good score on Tashir. “That she never could stand clandestine work, so she's not about to venture an opinion. Father's not to know. Savil is going to tell him I'm visiting with Liss. Yfandes is in favor, since she's going to be with me most of the time, and within reach when she's not actually with me.”

Jervis' shoulders relaxed a trifle. “That had me worried, a bit. But if you're taking the White Lady, I got no objections. If she can't get you out of a mess, nobody can. I got a lot of respect for that pretty little thing.”

:Tell him thank you, Chosen.:

Vanyel grinned. Jervis, unlike Withen, had no problem remembering that Yfandes was not a horse. He'd always offered her respect; since he and Vanyel had made their uneasy peace, he'd offered her the same kind of treatment she'd have gotten from another Herald. Yfandes was a person to Jervis; a little oddly shaped, but a person. Jervis actually got along with her better than he did with Vanyel. “She says to tell you, 'thank you.' I think she likes you.”

“She's a lovely lady, and I like her right back.” Jervis grinned at him. “There's been a couple of times I've wished I could talk to her straight out; I kind of wanted her to know I'm real pleased that she's on my side these days. Tashir! The boy won't break! Put some back in that swing! He's supposed to learn how to get out of the way, dammit!” Jervis stalked onto the floor of the salle, and Vanyel took the opportunity to get back to his room and pack up.

There was one other person who needed to know where Vanyel was going to be: Medren. This was in part because Vanyel needed to borrow his old lute. Disreputable minstrel Valdir could never afford Herald Vanyel's lute or the twelve – stringed gittern. And going in clandestine like this, Vanyel knew he'd better have no discrepancies in his persona. Vanyel had a battered old instrument he'd picked up in a pawn shop that he carried as Valdir, but he'd left it at Haven, not thinking he'd need it.

But there was a further reason; Tashir was relaxed and open with the boy in a way he was not with either Jervis or Vanyel. Vanyel had come to the conclusion that his nephew was older than his years in a great many ways, and Vanyel had confidence in his inherent good sense.

And, last of all, the boy had the Bardic Gift. That could be very useful in dealing with an unbalanced youngster that no one dared to Mindtouch.

In a kind of bizarre coincidence, they'd given Medren Vanyel's old room, up and under the eaves and across from the library. Vanyel stared out the window, and wondered if he was still up to the climb across the face of the keep to get to that little casement that let into the library.

“How long do you reckon you'll be over there?” Medren asked, sitting on his bed and detuning his old instrument carefully.

“Not long; about a fortnight altogether. Anything I can't find out in that time is going to be too deep to learn as a vagabond minstrel, anyway.” Vanyel turned away from the window.

“You aren't planning on going into that palace, are you?”

“No. Why?”

Medren shook his head. “I dunno. I just got a bad feeling about it. Like, you shouldn't go in there alone. As long as I think of you going in with somebody, the bad feeling goes away. That sound dumb?”

“No, that sounds eminently sensible.” Vanyel sat down beside him on the bed. Medren picked up the patched and worn canvas lute case and slid the instrument into it. “I want you to keep an eye on Tashir for me; a Bardic eye, if you will.”

The boy contemplated that statement for a moment, whistling between his teeth a little. “You mean keep him calmed down? He's as jumpy as a deer hearing dogs. I been trying to do a little of that. I – ” He blushed. “I remembered what you told me, about misusing the Gift. I thought this might be what you meant about using it right. He likes music well enough, so I just – sort of make it soothing.”

Vanyel ruffled his hair approvingly, and Medren gave him an urchinlike grin. “Good lad, that is exactly what I meant about using it properly. When you aren't enhancing a performance, proper use is to the benefit of your audience, or to the King's orders. And poor Tashir could certainly benefit by a little soothing. So keep him soothed, hmm? There's one other thing, and this is a bit more delicate. He may tell you things, things about himself. I hesitate to ask you to betray confidences, but we just don't know anything about him.”

Medren thought that over. “Seems to me that the awfuller the thing he'd tell me, and the less he'd want it known, the more you'd want to know it.” He chewed his lip. “That's a hard one. That's awful close to telling secrets I've been asked to keep. And if I've been making him feel like he could trust me, it doesn't seem fair.”

“I know. But I remind you that he's been accused of murdering fifty or sixty people. What he tells you might be a clue to whether or not he actually did it.” Vanyel forestalled Medren's protests with an uplifted hand. “I know what you're going to say, and if he did it, I don't believe he did it on purpose. But if – say – you found out where it was that his father wanted to send him, and why it frightened him so, we could have mitigating circumstances. I doubt the Lineans would totally accept it, but we would, and he could make a very pleasant home here with the Valdemar Heralds, even if he could never return to Lineas. That's not exactly a handicap.”

Medren nodded so vigorously that his forelock fell into his eyes. “Makes sense. Fine, then if he tells me stuff, I'll tell it to you.”

The boy stuffed a handful of the little coils of spare lute strings into a pocket on the back of the case and handed the whole to Vanyel. Vanyel stood, and pulled the carry strap over his shoulder. “Do I look the proper scruffy minstrel?” he asked, grinning.

Medren snorted. “You're never going to look scruffy, Van. You do look underfed, which is good. And if you didn't shave for a couple of days, that would be better.

Then, again – ” He contemplated Vanyel with his head tilted to one side. “If you didn't shave you'd look like a bandit, and people don't tell things to bandits. Better just stick to looking clean, starving, and pathetic. That way women'll feed you and tell you everything while they're feeding you. Hey, don't worry about that lute – if you gotta leave it, leave it. If you feel bad about leaving it, replace it.”

Vanyel placed his right hand over his heart and bowed slightly. “I defer to your judgment. Clean and starving it is, and if speed requires I leave the instrument, I shall. And I shall replace it. It's a good thing to have one old instrument that you needn't worry about, you never know when you'll want to take one – oh, on a picnic or something. Thank you, Medren. For everything.” He glanced out the window. “I want to get to Highjorune by nightfall, so we'd better get on it. Remember, I'm supposed to be on a side trip to see Liss. I sent her a message by one of Savil's birds, so Liss knows to cover for me.”

Medren nodded. “Right. And I'll keep a tight eye on Tashir for you, best I can.”

“That's all I can ask of anyone.”

Sunset was a thing of subdued colors, muted under a pall of gray clouds. Vanyel slipped off Yfandes' back, and uncinched the strap holding the folded blanket he'd used as a makeshift riding pad. Bareback for most of a day would not have been comfortable for either of them, but he had no place to hide her harness. No problem; they'd solved this little quandary the first time he became minstrel Valdir. She wore no halter at all, and only the blanket that he would use if he had to sleep in stables or on the floor of some inn. Nothing to hide, and nothing to explain. Yfandes would keep herself fed by filching from farms and free-grazing. If she got too hungry, he'd buy or steal some grain and toss it out over the wall to her at night.

:Be careful,: she said, nuzzling his cheek. :I love you. I'll be staying with you as much as I can, but this is awfully settled land. I may have to pull off quite a ways to keep from getting caught.:

:I have all that current-energy to pull on if I have to call you,: he reminded her. :It's not the node, but it wouldn't surprise me to find out I could boost most of the way back to Forst Reach with it. I'm planning on recharging while I'm here, anyway.:

:If Vedric is still here, that could be dangerous.:

:Only if he detects it.: He cupped his hand under her chin and gazed into those bottomless blue eyes. :I'll be careful, I promise. This isn't Karse, but I'm going to behave as if it was. Enemy territory, and full drill.:

:Then I'm satisfied.: She tossed her head, flicking her forelock out of her eyes. :Call me if you need me.:

:I will.: He watched her fade into the underbrush of the woodlot beside him with a feeling of wonderment. How something that big and that white could just-vanish like that – it never ceased to amaze him.

He rolled the cinch-belt, folded the blanket, and stuffed both into the straps of his pack. With a sigh for his poor feet, he hitched the lute strap a little higher on his shoulder, and headed toward the city gates of Highjorune.

The road was dusty, and before he reached the gates he looked as if he'd been afoot all day. He joined the slow, shuffling line of travelers and workers returning from the farms, warehouses, and some of the dirtier manufactories that lay outside the city walls. Farmworkers, mostly; most folk owning farms within easy walking distance of Highjorune lived within the city walls, as did their hirelings, a cautious holdover from the days when Mavelan attacks out of Baires penetrated as far as the throne city. The eyes of the guard at the gate flickered over him; noted the lute, the threadbare, starveling aspect, and the lack of weaponry, and dismissed him, all in a breath. Minstrel Valdir was not worth noting, which made minstrel Valdir very happy indeed.

Well, the first thing a hungry minstrel looks for is work, and Valdir was no exception to that rule. He found himself a sheltered corner out of the traffic, and began to assess his surroundings.

The good corners were all taken, by a couple of beggars, a juggler, and a man with a dancing dog. He shook his head, as if to himself. Nothing for him here, so close to the gates. He was going to need a native guide.

He loitered about the gate, waiting patiently for the guard to change. He put his hat out, got the lute in tune, and played a little, but he really didn't expect much patronage in this out-of-the-way nook. He actually drew a few loiterers, much to his own amazement. To his further amazement, some loiterers had money. By the time the relief-guard arrived with torches to install in the holders on either side of the gate, he'd actually collected enough coppers for a meager supper.

He had something more than a turnip and stale bread-crust on his mind, however. It was getting chilly; his nose was cold, and his patched cloak was doing very little to keep out the bite in the air. He chose one of the guards to follow, a man who looked as if he ate and drank well, and had money in his pocket; he slung the lute back over his shoulder, and sauntered along after him at a discreet distance.

It was possible, of course, that the man was married – but he was unranked, and young, and that made it unlikely. There was an old saying to the effect that, while higher-ranked officers had to be married, anyone beneath the rank of sergeant was asking for trouble if he chose matrimonial bonds. “Privates can't marry, sergeants may marry, captains must marry.” Valdir had noticed that, no matter the place or the structure of the armed force, that old saying tended to hold true.

So, that being the case, an unranked man was likely to find himself a nice little inn or taphouse to haunt. And establishments of the sort he would frequent would tend to cater to his kind. They would have other entertainments as well – and they were frequently run by women. Valdir had traded off his looks to get himself a corner in more than one such establishment.

The man he was following turned a corner ahead of him, and when Valdir turned the same corner, he knew he'd come to the right street. Every third building seemed to be an alehouse of one sort or another; it was brightly lit, and women of problematical age and negotiable virtue had set up shop – as it were – beneath each and every one of the brightly burning torches and lanterns. Valdir grinned, and proceeded to see what he could do about giving those coppers in his purse some company.

The first inn he stuck his nose into was not what he was looking for. It was all too clearly a place that catered to appetites other than hunger and thirst. The second was perfect – but it had a musician of its own, an older man who glared at him over the neck of his gittern in such a way as left no doubt in Valdir' mind that he intended to keep his cozy little berth. The third had dancers, and plainly had no need of him, not given the abandon with which the young ladies were shedding the scarves that were their principle items of clothing. The fourth and fifth were run by men; Valdir approached them anyway, but the owner of the fourth was a minstrel himself, and the owner of the fifth preferred his customers with cash to spare to spend it in the dice and card games in the back room. The sixth was – regrettable. The smell drove him out faster than he'd gone in. But the seventh – the seventh had possibilities.

The Inn of the Green Man it was called; it was shabby, but relatively clean. The common stew in a pot over the fire smelled edible and as if it had more than a passing acquaintance with meat, though it was probably best not to ask what species. It was populated, but not overcrowded, and brightly lit with tallow dips and oil lamps, which would discourage pickpockets and cutpurses. The serving wenches – whose other properties were also, evidently, for sale – were also relatively clean. They weren't fabulous beauties, and most of them weren't in the first bloom of youth, but they were clean.

There was a good crowd, though the place wasn't exactly full. And Valdir spotted his guide here as well, which was a good omen.

Valdir stuck a little more than his nose in the door, and managed to get the attention of one of the serving wenches. “Might I have a word with the owner?” he asked, diffidently.

“Kitchen,” said the hard-faced girl, and gave him a second look. He contrived to appear starving and helpless, and she softened, just a little. “Back door,” she ordered. “Best warn you, Bel don't much like your kind. Last songbird we had, run off with her best girl.”

“Thank you, lady,” Valdir said humbly. She snorted, and went back to table-tending.

Valdir had to make his way halfway down the block before he could find an accessway to the alley. He caught a couple of young toughs eyeing him with speculation, but his threadbare state evidently convinced them that he didn't have much to steal -

That, and the insidious little voice in their heads that said Not worth bothering with. He doesn't have anything worth the scuffle.

The alley reeked, and not just of garbage, and he was just as glad that he hadn't eaten since morning. He risked a mage-light, so that he could avoid stepping in anything – and when it became evident that there were places he couldn't do that, he risked a little more magic to give him a clean spot or two to use as stepping stones.

Kind of funny, he thought, stretching carefully over a puddle of stale urine. It was because I couldn't face situations like this that I never ran away to become a minstrel. And now, here I am – enacting one of my own nightmares. Funny.

He finally found the back door of The Green Man and pushed it open. The kitchen, also, was relatively clean, but he didn't get to see much of it, because a giantess blocked his view almost immediately.

If she was less than six feet tall, Valdir would have been surprised. The sleeves of her sweat-stained linen shirt were rolled up almost to the shoulder, leaving bare arms of corded muscle Jervis would have envied. She wore breeches rather than skirts, which may have been a practical consideration, since enough materials to make her a skirt would have made a considerable dent in a lean clothing budget. Her graying brown hair was cut shorter than Valdir's. And no one would ever notice her face – not when confronted with the scar that ran from left temple to right jawbone.

“An' what d'you want?” she asked, her voice a dangerous-sounding growl.

“The – the usual,” faltered Valdir. “A place, milady ... a place for a poor songster. ...”

“A place. Food and drink and a place to sleep in return for some share of whatever paltry coppers ye manage to garner,” the woman rumbled disgustedly. “Aye, and a chance t' run off with one o' me girls when me back's turned. Not likely, boy. And ye'd better find yerself somewhere else t' caterwaul; there ain't an inn on th' Row that needs a rhymester.”

Valdir made his eyes large and sad, and plucked at the woman's sleeve as she turned away. “My lady, please – ” he begged shamelessly. “I'm new-come, with scarce enough coppers to buy a crust. I pledge you, lady, I would treat your other ladies as sisters.”

She rounded on him. “Oh, ye would, would you? Gull someone else! If ye're new – come, then get ye new-gone!”

“Lady,” he whimpered, ducking her threatened blow. “Lady, I swear – lady – I'm-” he let his voice sink to a low, half-shamed whisper, “ – lady, your maids are safe with me! More than safe – I'm – shaych. There are few places open for such as I -”

She stared, she gaped, and then she grinned. “ Struth! Ye could be at that, that pretty face an' all! Shaych! I like that!” She propelled him into the kitchen with a hand like a slab of bacon. “All right, I give ye a chance! Two meals an' a place on th' floor for half yer takin's.”

He knew he had to put up at least the appearance of bargaining – but not much, or he'd cast doubt on his disguise. “Three meals,” he said, desperately, “and a quarter.''

She glared at him. “Ye try me,” she said warningly. “Ye try me temper, pretty boy. Three an' half.”

“Three and half,” he agreed, timidly.

“Done. An' don't think t' cheat me; me girls be checkin' ye right regular. Now – list. I got armsmen here, mostly. I want lively stuff; things as put 'em in mind that me girls serve more'n ale. None of yer long-winded ballads, nor sticky love songs, nor yet nothin' melancholy. Not less'n they asks for it. An' if it be melancholy, ye make 'em cry, ye hear? Make 'em cry so's me girls an' me drink can give 'em a bit 'o comfort. Got that?”

“Aye, lady,” he whispered.

“Don't ye go lookin' fer a bedmate 'mongst them lads, neither. They wants that, there's the Page, an' that's where they go. We got us agreements on the Row. I don' sell boys, an' I don' let in streetboys; the Page don' sell girls.”

“Aye, lady.”

“Ye start yer plunkin' at sundown when I open, an' ye finish when I close. Rest of th' time's yer own. Get yer meals in th' kitchen, sleep in th' common room after closin'.”

“Aye, lady.”

“Now – stick yer pack over in that corner, so's I know ye ain't gonna run off, an' get out there.”

He shed pack and cloak under her critical eye, and tucked both away in the chimney corner. He took with him only his lute and his hat, and hurried off into the common room, with her eyes burning holes in his back.

She was in a slightly better mood when she closed up near dawn. Certainly she was mollified by the nice stack of copper coins she'd earned from his efforts. That it was roughly twice the value of the meals she'd be feeding him probably contributed to that good humor. That no less than three of the prettiest of her “girls” had propositioned him and been turned down probably didn't hurt.

She was pleased enough that she had a thin straw pallet brought down out of the attic so that he wouldn't be sleeping on the floor. He would be sharing the common room with an ancient gaffer who served as the potboy, and the two utterly silent kitchen helpers of indeterminate age and sex. Her order to all four of them to strip and wash at the kitchen pump relieved him a bit; he wasn't looking for comfort, but he had hoped to avoid fleas and lice. When the washing was over, he was fairly certain that the kitchen helpers were girls, but their ages were still a mystery.

When Bel left, she took the light with her, leaving them to arrange themselves in the dark. Valdir curled up on his lumpy pallet, wrapped in his cloak and the blanket that still smelled faintly of Yfandes, and sighed.

:Beloved?: He sent his thought-tendril questing out into the gray light of early dawn after her.

:Here. Are you established?:

:Fairly well. Valdir's seen worse. At least I won't be poisoned by the food. What about you ?:

:I have shelter. :

:Good.: He yawned. :This is strictly an after-dark establishment; if I go roaming in the late morning and early afternoon, I should find out a few things.:

:I wish that I could help.: she replied wistfully.

:So do I. Good night, dearheart. I can't keep awake anymore.:

:Sleep well.:

One thing more, though, before he slept. A subtle, and very well camouflaged tap into the nearest current of mage-power. He needed it; the tiny trickle he would take would likely not be noticed by anyone unless they were checking the streams inch by inch. It wouldn't replenish his reserves immediately, but over a few days it would. It was a pity he could only do this while meditating or sleeping. It was an even greater pity that he couldn't just tap straight in as he had the night he'd rescued Tashir; he'd be at full power in moments if he could do that.

But that would tell Lord Vedric Mavelan that there was another mage here.

And if it comes to that, I'd rather surprise him.

He'd intended to try and think out some of his other problems, but it had been a full day since he'd last slept, and the walking he'd done had tired him out more than he realized. He started to try and pick over his automatic reactions to Bel's “girls”; had he led them on, without intending to? Had he been flirting with them, knowing deep down that he was going to turn them down and enjoying the hold his good looks gave over them? It was getting so that nothing was simple anymore.