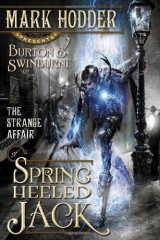

Текст книги "The strange affair of Spring-heeled Jack"

Автор книги: Mark Hodder

Жанр:

Детективная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 16 (всего у книги 26 страниц)

Darwin gestured to Swinburne's right. The poet looked but saw only bulky contrivances, sparking electrodes, cables, pipes, flashing lights, and objects his eyes could barely interpret.

Something moved.

It was the front of a large lozenge-shaped contraption, a slab of metal into which dials and gauges were set, standing upright but inclined slightly backward. It occurred to the poet that it somewhat resembled a sarcophagus, whose lid was now lifting of its own accord.

White vapour burst from its sides and fell as snowflakes to the floor.

The lid slid forward then silently glided to one side, revealing the contents within.

Swinburne saw a naked man whose pale skin glistened with frost. Tubes entered his flesh from the inside edges of the metal coffin, piercing the skin of his scarred thighs, of his arms and his neck. The upper-left side of his head was missing. The left eye had been replaced with some sort of lens set in rings of brass. Above this, where there should have been forehead and scalp, there was a studded brass dome with a glass panel-like a small porthole-in its front. Just above the ear, a winding key projected.

The human part of the man's face was settled in repose and, though the bushy beard had been removed, Swinburne at once recognised the features.

"Good Lord!" he gasped. "John Hanning Speke!"

"Yes," affirmed Darwin. "Soon he will be recovered sufficiently to serve us. As you see, the left lobe of his brain has been replaced with a babbage."

"A what?"

"A probability calculator crafted by our colleague, Charles Babbage. It will, among a great many other things, magnify Mr. Speke's ability to analyse situations and formulate strategic responses to them. The device is powered by clockwork, for portability."

"He agreed to this?" mumbled Swinburne.

"He was in no position to agree or disagree. He was unconscious and dying. We saved his life."

The sarcophagus slid shut, hiding Speke from view.

"Algernon Charles Swinburne," said Darwin, levelling his gimlet eyes at the poet, "we would now analyse your response. Speak."

Swinburne stared bleakly at his captor.

He coughed and licked his lips.

"To summarize," the poet said, hoarsely, "you are flooding the Empire with new machines that will destabilise the current social order; you intend to create a new social order comprised of specialist humans who will serve as drones in what amounts to a scientific hive; and you are interfering with animal biology in order to manufacture a sublevel of mindless slaves. All this to expand the British Empire, under the rule of scientists, until it dominates the entire world. Am I right?"

Darwin nodded his huge head and said, "We are impressed by his ability to reduce the complex to a simplistic statement which is, nevertheless, essentially correct."

"And you want my response?" asked Swinburne.

"Yes, we do."

"Very well then; here it is. You are completely, profoundly, and irreversibly fucking niad.!"

With a blast of steam, Isambard Kingdom Brunel slowly lifted his great frame until it towered over the little poet.

"It's quite all right, Isambard," said Darwin. "Calm yourself."

The great machine froze, but for the piston on one shoulder, which rose and fell slowly, and the bellows on the other, which creaked and gasped like the respiration of a dying man.

"It's absurd!" shrilled Swinburne. "Quite apart from the moral and ethical issues, how in blue blazes can you expect to accurately monitor the three branches of the experiment when you are conducting them simultaneously in the same arena? And what about the time factor? The chimney sweeps, for example! Information from such an experiment will take generations to gather! Generations! Do you expect to live forever?"

For a third time, Darwin's rattling laugh sounded between the fizzle and claps of electrical charges.

"He has surprised us!" he declared. "He has pierced to the heart of the matter! Time, indeed, is the key, Algernon Charles Swinburne. However, we have-"

"Stop!"

The cry rang out from somewhere behind the poet, so loud that it echoed above the chamber's general cacophony.

"What is this interruption?" demanded Darwin, and Francis Galton's body jerked two paces forward, dragging the long cable behind it, raising its arm and brandishing the syringe like a weapon.

With a whirring noise, one of Brunel's arms shot out and a metal clamp closed on the automaton's wrist.

Bells clanged.

"Forgive us, Isambard; we were taken by surprise, that is all. Come here, Mr. Oliphant; explain yourself."

As Brunel's arm retracted and Galton's lowered, Laurence Oliphant stepped into view.

"My hat!" exclaimed Swinburne. "What a merry freak show this is!"

Oliphant threw him a malicious glance. "I don't see a mark on his forehead," said the albino. His smooth tones made the poet shudder. "Have you extracted any cells?"

"There was no need," answered Darwin. "For, despite appearances to the contrary, he is not a boy but a man."

"I know. He's Swinburne, the poet. The little idiot has been much in the company of Burton these past days."

"Is that so? We were not aware of this."

Oliphant banged the end of his cane on the floor impatiently.

"Of course not!" he snapped. "You've been too busy revealing your plans to question him about his own!"

"It was an experiment."

"Blast it! You are a machine for observing facts and grinding out conclusions, but did it not cross your minds that in telling him about the programme you are giving information to the enemy?"

"We were not aware that he is an enemy."

"You fool! You should consider every man a potential enemy until he is proven otherwise."

"You are correct. It was an interesting exercise but the experiment is finished and we are satisfied. Algernon Charles Swinburne is of no further use to us. You may dispose of him outside."

"I'll do it here," said Oliphant, drawing the rapier from his cane.

"No," said Darwin. "This is a laboratory. It is a delicate environment. There must be no blood spilled here. Do it in the courtyard. Question him first. Find out how much Burton knows. Then dispose of the corpse in the furnace."

"Very well. Release him. Mr. Brunel, bring him outside, please."

The blank-eyed Francis Galton placed the syringe back onto the trolley, approached Swinburne, and began to unbuckle the straps. One of Brunel's limbs unfolded and the digits at its end clamped shut around the poet's forearm.

"Get offl" screamed Swinburne. "Help! Help!"

"Enough of your histrionics," snarled Oliphant. "There's no one to hear them and I find them irritating."

"Sod off!" spat Swinburne.

Galton pulled open the last of the straps and Brunel swung the little poet up into the air.

"Ow! Ow! I can walk, curse you!"

"Follow," commanded Oliphant.

With Isambard Kingdom Brunel clanking and thudding along behind, holding the kicking and squealing Swinburne high, Laurence Oliphant crossed the vast laboratory and passed through huge double doors into a large rectangular courtyard. Swinburne was surprised to see a noonday sky abovehe had no idea how long he'd been unconscious.

He instantly recognised the location: he was in Battersea Power Station, which towered around this central enclosure, a colossal copper rod rising up in each of the four corners.

"Drop him."

Brunel released the poet, who landed in a heap on the wet ground.

Oliphant held the point of his blade at Swinburne's throat.

"You may go, Brunel."

A bell chimed and the hulking machine stamped back through the doors, which closed behind it.

Oliphant stepped away and sheathed his rapier. He turned and loped across the courtyard to the entrance, a big double gate into which a normalsized door was set. This latter he unbolted and opened.

"Your escape route." He smiled, his pink eyes glinting, the vertical pupils narrowing. He moved away from the exit. "Go! Run!"

Algernon Swinburne looked at the albino curiously. What was he playing at?

He scrambled to his feet and began to walk toward the door. Oliphant continued to move away, giving the poet more and more space.

"Why?" asked Swinburne.

Oliphant remained silent, the smile playing about his face, the eyes following Swinburne's every step.

The poet shrugged and increased his pace.

He was less than four feet from the portal when Oliphant suddenly sprang at him.

Swinburne shrieked and ran but the albino was phenomenally fast and swept down on the little man in a blur of movement, grabbing Swinburne by the back of the collar just as he was stepping across the threshold and yanking him backward.

Swinburne flew through the air, hit the ground, rolled in a spray of rainwater, and found himself lying exactly where Brunel had dropped him.

Oliphant cackled; a cruel, vile noise.

Swinburne staggered to his feet. "Cat and mouse," he said under his breath. "And I'm the bloody mouse!"

THE TRAIL

When we adjust some element of an animal's nature, a quite different element alters of its own accord, as if there is some system of checks and balances at work. What we cannot fathom is why the unplanned changes seem entirely pointless from a functional perspective. I an baffled. Glalton is baffled. Darwin is baffled. All we can do is experiment, experiment, experiment!

– from a NIGHTINGALE

Sir Richard Francis Burton arrived at the Squirrel Hill Cemetery and quickly found the area where the loops-garous had been feeding. Graves had been torn open, coffins ripped apart, and putrefying corpses shredded and gnawed at, left scattered across the wet mud.

Even though, while in Africa, he'd become fascinated by the notion of cannibalism, Burton actually possessed a deep-seated fear of the ghoulish. Anything connected with graveyards and corpses unnerved him. The many cadavers he'd seen, and even accidentally trodden on, in the East End had filled him with horror; Montague Penniforth's ravaged carcass had sickened him to the core; and now this! His mouth felt dry and his heart hammered in his chest.

At his feet, Fidget growled and whined and pulled at his leash.

Burton squatted and took the dog's head in his hands, looking into the big brown eyes.

"Listen, Fidget," he said quietly. "This damned rain has probably washed away the scent but somehow you have to find it. Do you understand? My friend's life depends on it!"

He took from his pocket a pair of Swinburne's white gloves and pressed them against the basset hound's nose.

"Seek, Fidget! Seek!"

The dog yelped and, as Burton stood, started to snuffle about enthusiastically, moving in an ever-widening circle. Repeatedly, as he came close to the scattered bones and lumps of worm-ridden flesh, he let loose a coughing bark-wuff./-which Burton guessed indicated not the odour of the corpses but the scent of the werewolves. This could be useful, for if their musk was that strong, it would be easier for the dog to follow them than Swinburne.

Ultimately, this proved to be the case. Fidget led him to an area of the cemetery where, even after the rainfall, it was obvious that a struggle had taken place. Deep grooves showed where boot heels had been dragged through the mud and around them were the many footprints of loups-garous. Then all indications of Swinburne's presence vanished and the paw marks trailed away toward a collapsed section of the graveyard's wall.

"They picked him up and carried him," muttered Burton.

Fidget was gazing at him with an apologetic expression. Swinburne's trail had vanished.

"Don't worry, old fellow, the game's not over yet!"

Burton pulled Fidget over to the gap in the wall, stepped through, crouched, and pushed the dog's nose into one of the werewolf paw prints.

A deep rumble sounded in the basset hound's chest and his snout wrinkled in disgust.

"Follow!" ordered Burton.

Fidget whined, gave a yelp, and pulled his master back toward the cemetery.

"No! Wrong direction! That way! Go!"

The hound stopped, blinked at him, looked back along the trail, turned, and started away from the wall.

"Good dog!" encouraged his new master.

Dragged along behind the excited hound, the king's agent descended the hill, skirted a long fence, and passed into a rubbish-strewn alleyway that ran between the backyards of terraced houses until it emerged onto Devonport Street. Fidget turned to the right and raced along, down the inclining road and across the main thoroughfare of Cable Street toward the Thames. Burton was astonished at the dog's assured manner. The rain had been falling for hours, yet enough of the werewolves' scent remained for the remarkable hound to follow.

People milled about, many turning to stare at the man and the small basset hound; there were yells and catcalls but Burton barely noticed, so intent was he on his quest.

Reaching the bank of the river, they turned right again, following the course of the Wapping Wall. The terrible reek of the city's artery assailed Burton's nostrils and turned his stomach, yet Fidget kept on, his nose able to separate one stink from another, pushing aside the distractions, focusing only on that which he'd been ordered to follow.

With the horrors of the Cauldron seething around them, they pressed on in a westerly direction for nearly two miles until London Bridge hove into view in the distance. Across the road, Burton spotted the end of Mews Street and the boarded-up pawnshop where he'd met with Paul Gustave Dore.

Past the docks and the Tower of London went the man and his hound, and down a set of stone steps to a narrow walkway that ran alongside the contaminated waters of the Thames. The stone surface was slick with slime and, though the rain had abated somewhat, the muck squelched beneath Burton's tread and footing was precarious. One slip and he could end up in the river!

They passed into the gloom beneath London Bridge and there Fidget stopped and snuffled at the base of a narrow wooden door upon which a notice warned "Strictly No Entry." Burton put his shoulder to the portal and pushed. With a deep grinding noise, it scraped open, revealing a square chamber.

The king's agent reached into his coat pocket, withdrew a clockwork lantern, and gave it a twist. The flame flared into life inside it and the sides of the device spilled light into the room. It was completely empty but for muddy paw prints on the floor which led through a dark archway in the opposite wall. Urged onward by the dog, Burton pushed the door shut and crossed the chamber. Beyond the archway, stone steps descended into darkness. He followed them.

The deeper he went, the damper it became, until the stone walls were literally running with water. After many minutes had passed, he finally came to the base of the stairs and here found a corridor cut through solid rock, its floor hidden beneath filthy water, with three thick pipes running along the lefthand wall. Gas mains, he supposed.

"You'll not sniff out their trail here," he muttered to Fidget, "but this is the way they must have come, so we'll press on. Here-up with you!"

He bent and hoisted the basset hound up into his arms, then moved down into the cold water. Two steps he descended until he reached the flat floor. The liquid swirled around his knees, filling his boots and clogging his nostrils with the putrid stench of rotting fish.

Droplets fell from above, hitting the water with echoing and strangely musical plops.

He waded along the narrow tunnel, his lantern ticking in his hand, casting its fitful glow on the streaming walls and metal pipes, which shimmered and glistened in the light. Soon there was total darkness ahead, total darkness behind, and Burton experienced the same sensation he'd had when rising through the fog in the rotorchair: that he was moving but going nowhere; that this journey had no end.

He pressed on.

He was under the Thames, that was obvious, and the thought of that great weight above terrified him. He'd never been good with enclosed spaces. Bismillah! What he'd give now for the endless plains of Africa or the evershifting desert sands of Arabia!

"Why did I agree to this?" he whispered into Fidget's ear. "Serving an Empire whose actions I deplore, in a country I can't call home?"

Fidget whimpered and rested his chin on his master's shoulder.

Eventually, and quite unexpectedly, the tunnel ended at a Hight of stairs.

Breathing a heartfelt sigh of relief, Burton stepped out of the water and ascended. He came to a room in every way identical to the one at the other end of the subterranean passage, and, setting Fidget onto the floor, he pushed the hound's nose into a paw print.

"Follow! There's a good boy!"

The dog crossed to the door opposite the entrance to the stairs and looked meaningfully at Burton, as if to say, "Open it!"

The famous adventurer did so and stepped out onto another slimecovered walkway. He was still beneath London Bridge but now on the Southwark side. He snapped off his lantern and shoved it into a pocket.

Fidget led him up onto Tooley Street, where he was met with a scene of utter devastation. This part of London, the Hay's Wharf area, had been completely destroyed by a disastrous fire back in June. Its warehouses had burned for two weeks, and even now, three months later and with the rain falling upon it, the wreckage was still visibly smouldering. To the east, almost as far as the eye could see, lay a ravaged landscape; a black wasteland sprawling beneath a dirty haze that even the rain couldn't wash away.

Burton winced. This was a painful sight, for among the warehouses had been Grindlays, the place where he'd stored the bulk of the Oriental manuscripts he'd spent so much of his Army pay on while in India, plus trunks filled with Oriental and African costumes and mementoes, and a great many of his personal notebooks.

It had all been consumed by the blaze.

He remembered with grim amusement how the clerk at Grindlays' head office, upon seeing his distress, had asked, "Did you lose any plate or jewellery, sir?"

"No, nothing of that nature," had replied Burton.

"Ah, well!" exclaimed the clerk, looking much happier. "That's not so bad then!"

Fidget tugged at his leash.

They turned westward and followed the river as far as Southwark Bridge before then turning inland. With his nose close to the ground, Fidget pulled the king's agent into a bystreet and from there into the depths of the borough.

Burton could see that the route the basset hound was following would probably be quiet at night but now it was past midday and the streets were thronged with citizens going about their business. Pushing their way through the crowds, the man and the dog passed through alley after alley, out of the borough and into Lambeth, through Lambeth and on to Vauxhall, until they finally emerged on Nine Elms Road. Here, the scent trail veered off the highway and through a hole in a wooden fence. It continued ahead, running parallel to the thoroughfare, and already Burton had an idea of the destination, for the sky in front of him was broken by four tall chimneylike structures.

Swinburne couldn't stop laughing.

His entire body hurt. He was bruised and lacerated and every injury was sending a thrill of pleasure coursing through his nerves.

Laurence Oliphant was being driven to a blind fury. He'd thrown down his sword cane, removed and dropped his jacket, rolled up his shirtsleeves, and was now setting about the poet with unrestrained viciousness.

Oh yes, he was going to kill the little man, but he'd be damned if he'd make it easy for the redheaded pipsqueak! No, a long, slow, terrifying death, that's what Swinburne was going to get.

So again and again he allowed his prey to reach that temptingly open door, and again and again he pounced on him at the last second and hurled him back into the courtyard.

And Swinburne laughed.

Oliphant circled the poet, grinned diabolically, swooped in, and struck. Swinburne spun into the air and thudded onto the ground, his clothes shredded, the skin beneath ripped.

He dragged himself along, a ragged, bloodied mess, his eyes wild, his giggle becoming a gurgle as blood streamed from his nose and split lips.

In four long strides, Oliphant was at his side.

"What are you?" gasped Swinburne. "One of Nurse Nightingale's foul experiments?"

"Shut your mouth!"

"What did she do to you, Oliphant?"

"She saved me."

"From what?"

"Death, Swinburne, death. I overindulged in opium, became an addict, and slipped into a coma in a Limehouse drug den. Miss Nightingale rescued the functioning parts of my brain and fused them with a humanised animal."

"What animal?"

"My white panther."

"Ah, that explains it!"

"Explains what?"

"The lingering odour of cat piss I smell every time you come close."

Oliphant emitted a ferocious hiss, grabbed the poet-one hand clutching the back of his neck, the other his right thigh-lifted him, whirled around, and flung him high into the air. Swinburne smashed into the base of a wall, dropped, rolled loosely, and lay still, his green eyes level with the ground, watching the albino's feet approaching.

Through bubbling blood, he croaked:

"Thou hast conquered, 0 pale Galilean;

The world has grown grey f -om thy breath;

We have drunken from things Lethean,

And fed on the fullness of death."

Oliphant bent over him. "Run, little man," he whispered. "Run for the door."

Swinburne rolled onto his back and looked up into the wicked pink eyes.

"Thank you," he mumbled. "But I have it in mind to lie here and compose a poem or two, if you don't mind."

"I mind," answered Oliphant. He grabbed the poet's throat and yanked him up. Then he lifted him off his feet, fingers tight around the skinny neck, and watched with interest as his victim's face began to darken.

Swinburne kicked and struggled, clutching at his assailant's wrists, but couldn't break free.

He caught sight of something over Oliphant's shoulder and suddenly relaxed, hanging limply.

Somehow, he managed to smile.

Oliphant looked at him in wonder.

A deep, commanding voice rang out: "Drop him!"

The albino whirled.

Sir Richard Francis Burton stood just inside the gate. He had picked Oliphant's swordstick up and held it, unsheathed, in his hand. At the adven turer's feet, a small dog backed toward the door, stepped through, and hid behind it, peeking out at Oliphant.

"Burton," breathed the albino.

He let go of Swinburne, who slumped to the ground and lay still, quietly chuckling.

"Come here, you bastard," snapped the king's agent.

"I'm unarmed," revealed Oliphant, walking forward with his arms spread wide.

"I don't care."

"That's not very gentlemanly."

"There are many who claim I am not a gentleman," noted Burton. "They call me Ruffian Dick. At this particular moment in time, it's a title I intend to live down to."

He suddenly sprang at Oliphant and thrust at his heart. The feline man twisted and jumped back, the point of the rapier catching and slicing his shirtsleeve.

"I'm too quick for you, Burton!" he panted, then, lightning fast, ducked down, pounced in, and swiped at the adventurer's thigh with his sharp talons.

Burton predicted the move and caught the albino's hand in his own.

"My reactions aren't bad either," he said.

His grip tightened and bones crunched.

Oliphant screamed.

Burton dropped the rapier and sent his fist crashing into the albino's jaw.

"And I think you'll find that I'm stronger."

With his left hand mercilessly breaking the bones in Oliphant's right, Burton set about pounding his opponent's face to a pulp. Blood spurted as the panther-man's nose snapped and flattened. Canine teeth broke. Skin tore.

Burton was thoroughly scientific about it. He revived the boxing skills of his youth, choosing where to strike with a cold detachment, timing his blows to perfection, measuring the damage to ensure that the albino suffered every crunching blow without slipping into unconsciousness.

It was more than punishment; it was torture, and Burton had no qualms about it.

As the beating continued, Fidget cautiously stepped back in through the door and began to skirt the wall toward Swinburne. Glancing repeatedly at his master, he padded around the edge of the big rectangular space then crept in until he reached Swinburne's feet. He sniffed at the blood-spattered boots, pushed his nose into the too-short trouser leg, then bit the skinny ankle.

"Yaargh!" screeched the poet.

Burton turned, and in that unguarded second, Laurence Oliphant ripped his mangled hand from the explorer's grasp and, with a sudden thrust of his legs, propelled himself away. He rolled, leaped to his feet, and sprinted to the huge doors of the power station. Perfectly balanced, they swung open at his touch and slammed shut behind him.

The king's agent, who'd instantly thrown himself after the albino, crashed into the doors, pushed them, pulled them, and realised that his enemy had escaped.

He hurried over to Swinburne and shoved Fidget away.

"Are you all right, Algy?"

"Bloody ecstatic, Richard."

"Can you walk?"

"I thought I could, then that blasted dog bit me!"

"Idiot. It was just a nip. Come on, up with you."

He slipped his arm beneath the poet's shoulders and heaved him upright. There was barely an inch of his friend that wasn't smeared with blood.

"I have to get you seen to as quickly as possible," he said. "We need to get this bleeding stopped."

"It was marvellous," gasped Swinburne. "I took everything he dished out! Was that courage, Richard?"

"Yes, Algy; that was courage."

"Splendid! Absolutely splendid! Oh, by the way, John Speke is in there."

Before Burton could reply, a howl echoed from the other end of the courtyard.

"Werewolves!" breathed the king's agent. "We've got to get out of here!"

He dragged his friend toward the door in the main gate, scooping up Oliphant's swords tick on the way, but before he got there half a dozen redcloaked wolf-men loped from an arched opening and came racing across the courtyard.

The head of the pack glared out from the shadow of its hood, displayed its sharp teeth in a terrible grin, extended a claw toward the retreating Englishmen, then exploded into flames.

The remaining creatures scattered, diving away from the sudden inferno. In the midst of this confusion, Swinburne thrust himself away from Burton, plunged at something on the ground, snatched it up, then launched himself through the door in the gate, knocking Burton backward. They landed in a heap outside the power station with Fidget tangled in their legs.

The king's agent pushed himself up, grabbed the door, and pulled it shut. There was no way to secure it from the outside, so, while the werewolves were distracted, there was only one thing to do: run!

He grabbed Swinburne, threw him over his shoulder, and took to his heels.

With the basset hound scampering along beside him, he sprinted westward over a patch of wasteland toward railway lines and, beyond them, the busy Kingstown Road and Chelsea Bridge.

"Hurry! They're coming!" cried Swinburne.

A quick backward glance proved the poet right: the loups-garous were pouring through the gate.

Despite his short legs, Fidget put on an astonishing show of speed and sprang ahead across the railway track. Burton tried to keep up but Swinburne's weight slowed him and now he spotted, to his right, a locomotive pelting down the line. There was no way, it seemed, to make it to the other side before the engine passed; his escape route was blocked and the wolf-men were gaining fast.

He set his mind to the task, sucked in a deep breath, and focused every ounce of his being into his pumping legs. Run! Run!

The events of the next few seconds happened so quickly that his consciousness couldn't register them, yet he dreamed about them for many months afterward.

The locomotive was upon him.

He put everything he had into a jump across its path.

His feet left the ground.

Claws ripped through the back of his jacket and ploughed through his skin.

A deafening whistle.

A wall of metal to his right.

Scalding vapour.

Gravel slamming into him.

Rolling.

A thunderous roar.

The blur of passing wheels and, under them, flames.

A receding rumble.

Slowly dissipating steam.

The grey sky.

A spot of rain on his face.

A groan at his side.

A moment of silence.

Then: "Ow! For Pete's sake! The blessed beast bit me again!"

Sir Richard Francis Burton started to laugh. It began in his stomach and rose through his chest and shook his whole body and he didn't want it to stop. He laughed at India. He laughed at Arabia. He laughed at Africa. He laughed at the Nile and the Royal Geographical Society and John Hanning bloody Speke. He laughed at Spring Heeled Jack and the wolf-men and the albino and that silly damned dog that kept biting Swinburne's ankle.

He laughed away his petulant anger, his resentments, his confusion, and his reluctance, and when he finally stopped laughing, he was Sir Richard Francis Burton, the king's agent, in the service of the country of his birth, and it no longer mattered that he was an outsider or that he stood in opposition to the Empire's foreign policies. He had a job to do.

His laughter abated. He lay silently and looked at the grey sky.

London muttered and grumbled.

He sat up and examined Swinburne. The poet had lapsed into unconsciousness. Fidget the basset hound was sitting at the little man's feet, happily chewing at a trouser leg.

The railway track was empty; the locomotive had disappeared from view behind a group of warehouses, though the tracks were still vibrating from its passing.

The loupr-garous were nowhere to be seen; all swept away by the train.

He stood, hoisted his friend back onto his shoulder, and, using Oliphant's cane to help him balance, walked down a gravel slope toward a wooden fence beyond which lay Kingstown Road.

He was halfway down when a loud throbbing filled the air.

Burton turned and looked back at the power station. An incredible machine was rising from it, seemingly pushed upward by the boiling cone of steam that belched from its underside. It was a rotorship; an immense oval platform of grey metal with portholes set along its edge. Its front was pointed and curved upward like the prow of a galleon and from the sides, like banks of oars, pylons projected outward. At their ends, atop vertical shafts, huge wings rotated faster than the eye could follow.