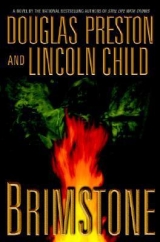

Текст книги "Brimstone"

Автор книги: Lincoln Child

Соавторы: Douglas Preston,Lincoln Child

Жанр:

Триллеры

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 32 (всего у книги 38 страниц)

"After sending Bullard off to stew about this, it was time to deal with Cutforth. I had Pinketts here purchase the apartment next to his, posing as an English baronet, to assist with the various, ah, arrangements . Like Grove, Cutforth scoffed at the idea at first. He'd been convinced my little show back in 1974 was a fraud. But as details of Grove's death emerged, he grew increasingly nervous. I didn't want him too nervous-just nervous enough to call Bullard and alarm him further. Which, of course, he did."

He issued a dry laugh.

"After Cutforth's death, your vulgar tabloids did a fabulous job beating the drum, whipping people into a frenzy. It was perfect. And Bullard fell apart. He was out of his mind. Then the colpo di grazia : I called Bullard and said that I had managed to cancel my contract with Lucifer!"

Fosco patted his hands together with delight. Watching, D'Agosta felt his stomach turn.

"He was desperate to know how. I told him I'd located an ancient manuscript explaining the devil would sometimes accept a gift in return for a human soul. But it had to be a truly unique gift, something of enormous rarity, something whose loss would debase the human spirit. I told him I'd sacrificed my Vermeer in just such a way.

"Poor Bullard was beside himself. He had no Vermeer, he said; nothing of value except boats, cars, houses, and companies. He begged me to advise him what he should buy, what he should give the devil. I told him it had to be something utterly unique and precious, an object that would impoverish the world by its loss. I said I couldn't advise him-naturally he couldn't know I was aware of the Stormcloud-and I said I doubted he owned anything the devil would want, that I had been hugely fortunate to have a Vermeer, that the devil surely would not have accepted my Caravaggio!"

At this witticism, Fosco burst into laughter.

"I told Bullard that, whatever it was, the devil had to have it immediately. The thirty-year anniversary of our original pact was nearing. Grove and Cutforth were already dead. There was not enough time for him to acquire something of the requisite rarity. I reminded him the devil would be able to see into his heart, that there would be no cheating the old gentleman, and that whatever he offered had better fit the bill or his soul would burn forever.

"That's when he finally broke down and told me he had a violin of great rarity, a Stradivarius called the Stormcloud-would that do? I told him I couldn't speak for the devil, but that I hoped for his sake it would. I congratulated him on being so fortunate."

Fosco paused to place another piece of dripping meat into his mouth. "I, of course, returned to Italy far earlier than I let on to you. I was here even before Bullard arrived. I dug an old grimoire out of the library here, gave it to him, told him to follow the ritual and place the violin inside a broken circle. Within his own, unbroken circle, he would be protected. But he must send away all his help, turn off the alarm system, and so forth-the devil didn't like interruptions. The poor man did as I asked. In place of the devil, I sent in Pinketts, who is devil enough, I can tell you. With theatrical effects and the appropriate garb. He took the violin and retreated, while I used my little machine to dispense with Bullard."

"Why the machine and the theatrics?" Pendergast asked quietly. "Why not put a bullet in him? The need to terrify your victim had passed."

"That was for your benefit, my dear fellow! It was a way to stir up the police, keep you in Italy a while longer. Where you would be easier to dispose of."

"Whether we will be easy to dispose of remains to be seen."

Fosco chuckled with great good humor. "You evidently think you have something to bargain with, otherwise you wouldn't have accepted my invitation."

"That is correct."

"Whatever you think you have, it won't be good enough. You are already as good as dead. I know you better than you realize. I know you because you are like me. You are very like me."

"You could not be more wrong, Count. I am not a murderer."

D'Agosta was surprised to see a faint blush of color in Pendergast's face.

"No, but you could be. You have it in you. I can see it."

"You see nothing."

Fosco had finished his steak and now he rose. "You think me an evil man. You call this whole affair sordid. But consider what I've done. I've saved the world's greatest violin from destruction. I've prevented the Chinese from penetrating the planned U.S. antimissile shield, removing a threat to millions of your fellow citizens. And at what cost? The lives of a pederast, a traitor, a producer of popular music who was filling the world with his filth, and a godless soul who destroyed everyone he touched."

"You haven't included our lives in this calculation."

Fosco nodded. "Yes. You and the unfortunate priest. Regrettable indeed. But if the truth be known, I'd waste a hundred lives for that instrument. There are five billion people. There is only one Stormcloud."

"It isn't worth even one human life," D'Agosta heard himself say.

Fosco turned, his eyebrows raised in surprise. "No?"

He turned and clapped his hands. Pinketts appeared at the door.

"Get me the violin."

The man disappeared and returned a moment later with an old wooden case, shaped like a small dark coffin, covered with the patina of ages. Pinketts placed it on a table next to the wall and withdrew to a far corner.

Fosco rose and strolled over to the case. He took out the bow, tightened it, ran a rosin up and down a few times, and then-slowly, lovingly-withdrew the violin. To D'Agosta, it didn't look at all extraordinary: just a violin, older than most. Hard to believe it had led them on this long journey, cost so many lives.

Fosco placed it under his chin, stood tall and straight. A moment of silence passed while he sighed, half closing his eyes. And then the bow began moving slowly over the strings, the notes flowing clearly. It was one of the few classical tunes D'Agosta recognized, one that his grandfather used to sing to him as a child: Bach's Jesu, Joy of Man's Desiring. The melody was simple, the measured notes rising, one after another, in a dignified cadence, filling the air with beautiful sound.

The room seemed to change. It became suffused with a kind of transcendent brightness. The tremulous purity of the sound took D'Agosta's breath away. The melody filled him like a presence, sweet and clean, speaking in a language beyond words. A language of pure beauty.

And then the melody was over. It was like being yanked from a dream. D'Agosta realized that, for a moment, he'd lost track of everything: Fosco, the killings, their perilous situation. Now it all came back with redoubled vengeance, all the worse for having been temporarily forgotten.

There was a silence while Fosco lowered the violin. Then he spoke in a whisper, his voice trembling. "You see now? This is not just a violin. It is alive . Do you understand, Mr. D'Agosta, why the sound of the Stradivarius is so beautiful? Because it is mortal. Because it is like the beating heart of a bird in flight. It reminds us that all beautiful things must die. The profound beauty of music lies somehow in its very transience and fragility. It breathes for a shining moment-and then it expires. That was the genius of Stradivari: he captured that moment in wood and varnish. He immortalized mortality."

He looked back at Pendergast, eyes still haunted. "Yes, the music always dies. But this "-he held up the violin-"will never die. It will outlive us all a hundred times over. Tell me now, Mr. Pendergast, that I have done wrong to save this violin. Please, say that I have committed a crime."

Pendergast said nothing.

"I'll say it," said D'Agosta. "You're a cold-blooded murderer."

"Ah, yes," Fosco murmured. "One can always count on a philistine to lay down absolute morality." He carefully wiped down the violin with a soft cloth and put it away. "Beautiful as it is, it isn't at its best. It needs more playing. I've been exercising it every day, fifteen minutes at first, now up to half an hour. It's healing already. In another six months, it will be back to its perfect self. I will loan it to Renata Lichtenstein. Do you know her? The first woman to win the Tchaikovsky Competition, a girl of only eighteen but already a transcendental genius. Yes, Renata will play it and go on to glory and renown. And then, when she can no longer play, my heir will loan it to someone else, and his heir to someone else, and so it will go down the centuries."

"Do you have an heir?" Pendergast asked.

D'Agosta was surprised by the question. But Fosco was not; he seemed to welcome it.

"Not a direct heir, no. But I shall not wait long to furnish myself with a son. I have just met the most charming woman. The only drawback is that she is English, but at least she can boast an Italian great-grandfather." His smile broadened.

As D'Agosta watched, Pendergast grew pale. "You are grotesquely deluded if you think she will marry you."

"I know, I know. Count Fosco is fat, revoltingly fat. But do not underestimate the power of a charming tongue to capture a woman's heart. Lady Maskelene and I had a marvelous afternoon on the island. We are both of the noble classes. We understand each other." He dusted his waistcoat. "I might even go on a diet."

This was greeted by a short silence. Then Pendergast spoke again. "You've showed us the violin. May we now see this little device that you spoke of? The device that killed at least four men?"

"With greatest pleasure. I'm very proud of it. Not only will I show it to you, I'll give you a demonstration."

D'Agosta felt a chill. Demonstration?

Fosco nodded to Pinketts, who took the violin and left the room. Within moments he returned with a large aluminum suitcase. Fosco unlatched the case and raised the lid, exposing half a dozen pieces of metal nestled in gray foam rubber. He began removing them, screwing them together. Then he turned and nodded to D'Agosta.

"Will you please stand over there, Sergeant?" he asked quietly.

{ 78 }

"Buck!" Hayward screamed again, fighting against an almost overwhelming panic. "Don't let them do this!" But it was hopeless; the roar of the crowd drowned out her voice, and Buck was in his tent, flaps closed, out of sight behind a wall of people.

The crowd was closing in now, the noose tightening fast. The ringleader-Buck's aide-de-camp, bolstered by increasingly frenzied followers-raised the hand with the rock. Watching him, Hayward saw his eyes widen, his nostrils flare. She'd seen that look before: it was the look of someone about to strike.

"Don't!" she shouted. "This isn't what you're about! It's against everything you stand for!"

"Shut up, centurion!" Todd cried.

She stumbled, righted herself. Even at this moment of extreme danger, she realized she could not show fear. She kept her eyes on Todd-he was the greatest threat, the match for the powder keg-and let her gun hand hover near her piece. As a last resort-a very last resort-she'd have to use it. Of course, once she did, that would be the end. But she wasn't going to go down like a cat under a pack of dogs.

Something about all this isn't right. Something was going on; something was being played out here that she didn't understand.

The cries of the crowd, their strange epithets, made no sense. Centurion. Soldier of Rome. What was this talk? Something Buck was subtly encouraging in recent sermons? And speaking of Buck, why had he seemed disappointed when she arrived-and then just walked away? Why the glassy, expectant look in his eyes? Something had happened to him, between this visit and the last.

What was it?

"Blasphemer!" Todd screamed. He took another step closer.

In response, the crowd tightened around Hayward. She had barely enough room to turn around now. She could feel rancid breath on the back of her neck; feel her heart beating like mad. Her hand strayed closer to the butt of her gun.

There was a pattern here, if only she could see it. There had to be.

She fought to stay rational. Her only way out of this was Buck himself. There was no other.

Quickly, she went back over her knowledge of deviant psychology, over Buck's possible motivations. What had Wentworth said? Possibly paranoid schizophrenic, potential for a Messianic complex. Deep down, she was still convinced Buck was no schizophrenic.

But a Messianic complex . ?

The need to be the Messiah. Perhaps-just perhaps-Wentworth was more right on that point than he knew.

Then, in an instant of revelation, it came to her. All of Buck's new hopes, new desires, were suddenly laid bare. This talk about Romans-they weren't talking about Roman Catholics. They were talking about real Romans. Pagan Romans. Centurions. The soldiers who came to arrest Jesus.

She suddenly understood the script Buck was following. That was why he ignored her, walked back into the tent. She didn't fit into his vision of what had to happen.

She faced the crowd, addressed them in her loudest voice. "A band of soldiers are coming to arrest Buck!"

This had a galvanic effect on the crowd. The yelling faltered a little, front to back, like the ripple of a stone on a pond.

"Did you hear!"

"The soldiers are coming!"

"They're coming!” Hayward yelled encouragingly.

The crowd took up the cry as she hoped they would, acting as a megaphone to Buck. “The soldiers are coming! The centurions are coming! "

There was a movement in the crowd, a kind of general sigh. As one group moved back, Hayward saw that Buck had reappeared at the door of his tent. The crowd seethed with expectation. Todd raised his rock once again, then hesitated.

It was the opening she needed. Momentary, but just enough to call Rocker. She slipped out her radio and bent forward, shielding herself from the crowd.

"Commissioner!" she called out.

For a moment, static. Then Rocker's voice crackled over the tiny speaker.

"What the hell's going on, Captain? It sounds like a riot. We're mobilizing, we're going in now and getting your ass out -"

"No!" Hayward said sharply. "It'll be a bloodbath!"

"She's using her radio!" Todd screamed. "Betrayer!"

"Sir, listen to me. Send in thirty-three men. Thirty-three exactly . And those undercover cops you've been using for on-site intel, the ones dressed like Buck's followers? Send in one of them. Just one. "

"Captain, I have no idea what you're-"

"Shut up, please, and listen . Buck has to act out the passion of Christ. That's how he sees himself. He's New York's sacrificial lamb. There's no other explanation for his behavior. So we've got to play along, let him act it out. The undercover cop, he's the shill, he's Judas, he's got to embrace Buck. Do you hear, sir? He’s got to embrace Buck. And then the cops move in and make the cuff. You do that, Commissioner, and there'll be no riot . Buck will go peacefully. Otherwise-"

"But thirty men? That's not enough-"

"Thirty-three. The number in a Roman band."

"Get her radio!” Hayward was jostled. She spun away, shielding her radio.

"Are you telling me Buck thinks-"

"Just do it, sir. Now! "

Hayward felt herself shoved hard from behind. She lost her grip on the radio, and it went flying into the crowd.

"Agent of darkness!"

Hayward had no idea if Rocker had understood. More to the point, she didn't know how the crowd would act. Buck might have his script, but would this frenzied mob follow it, too?

She looked toward Buck, who was now wading into the crowd. "Make way for the soldiers of Rome!" she yelled. "Make way!" She pointed southwest, the direction she knew the police would come from.

It was amazing: people were turning, looking. Buck himself was looking. He was standing, calm and tall, waiting for the drama to begin.

"Here they come!” others were yelling. "Here they come!"

There was a surge of confusion, a scuffling as the rest of the group began to arm themselves with rocks and sticks. Suddenly Buck held up his arms, tried to say something. The sound of the crowd fell.

"He's about to speak!” people called out. “Silence, everyone!"

Buck intoned in a deep, penetrating voice, "Make way for the centurions!"

This took everyone by surprise. Some took tighter grips on their makeshift weapons; others looked over their shoulders, in the direction of the approaching police. Still others looked at Buck, uncertain they had heard him correctly.

"This is as it should be!" Buck cried. "It is time to fulfill that which the prophets have spoken. Make way, my brothers and sisters, make way!"

The cry was taken up, at first raggedly, then with growing conviction. “Make way!"

"Do not fight them!" Buck cried. "Drop your weapons! Make way for the centurions!"

"Make way for the centurions!"

Buck spread his hands, and the crowd began to part hesitatingly before him.

As she watched, Hayward felt a flush spread through her limbs. It was working. The attention of the crowd had shifted from her. Only Todd, the aide-de-camp, seemed not to accept the change. He was still staring from her to Buck and back again, as if too caught up in the frenzy of the moment to shift direction.

"Traitor!" he barked at her.

And now, right on cue, a phalanx of cops came running through the distant trees toward them. Rocker had understood, after all: he'd come through. They waded into the outer fringes of the crowd, shoving and pushing with their riot shields. But already, with Buck's exhortations, the people were falling back.

"Let them pass!" Buck was crying, arms spread.

Now the cops were barreling down the open lane, trampling tents, shoving aside stragglers. As they broke into the open area before Buck's tent, there was a moment of panic and struggle. Todd raised his rock, fury twisting his features. "You did this, you bitch -!"

And the rock came flying, striking a glancing blow to Hayward's temple. She staggered back, fell to her knees, feeling the hot trickle of blood.

Suddenly Buck was there, his strong arms around her, raising her up and staying the crowd with his hand. "Put up thy swords! They have come to arrest me, and I will go with them peacefully! This is the will of God!"

Dazed, Hayward looked at Buck. He dabbed at her wound with a snowy handkerchief. "Suffer ye thus far," he murmured. His face was radiant, suffused with light.

Of course, she thought. Even this is part of the script.

There was more confusion. Someone embraced Buck-the shill at last-she heard Buck saying, "Judas, betrayest thou me with a kiss?"-and then the cops were all around, and he was pulled away from her. The cut on her head was bleeding freely, and she felt woozy.

"Captain Hayward?" she heard somebody call out. "Captain Hayward's been hurt!"

"Officer down! We need a medic!"

"Captain Hayward, you all right? Did he assault you?"

"I'm all right," she said, shaking away the wooziness as cops crowded around her, everyone trying to help. "It's nothing, just a scratch. It wasn't Buck."

"She's bleeding!"

"Forget it, it's nothing. Let me go." They released her reluctantly.

"Who was it? Who assaulted you?"

Todd was staring, humanity shocked back into him, horrified at what he'd done.

Hayward looked away. Another arrest right now could be disastrous. "Don't know. Came out of nowhere. It doesn't matter."

"Let's get you to an ambulance."

"I'll walk by myself," she said, brushing off yet another proffered arm. She felt embarrassed. It was nothing: scalp wounds always bled a great deal. She looked around, blinking her eyes. An immense silence seemed to have settled on the crowd. The police had the cuffs on Buck and had formed a semicircle around him, already moving him out. The crowd looked on, stunned, while Buck exhorted them to remain calm, be peaceful, hurt no one.

"Forgive them," he said.

All the momentum was gone. Buck had ordered them to stand down, and they had obeyed.

It was over.

{ 79 }

Immediately, D'Agosta pulled out his service piece and drew down on the count. "No fucking way," he said.

The count stared at the gun, sighing condescendingly. "Put away that gun, you fool. Pinketts?"

The manservant, who had left the room, now returned, carrying a large pumpkin in both arms. He set it down on the hearth before the fireplace.

"It is true, Sergeant D'Agosta, you would have been a much more effective demonstration. But it would have caused such a mess. " Fosco went back to assembling the device.

D'Agosta moved slowly backward, slipping his gun back into his holster as he did so. Somehow, the act of drawing his weapon brought fresh resolve. He and Pendergast were both armed. At the first indication of trouble, he would have no hesitation about taking out both the count and Pinketts. Except for some kitchen help, there didn't seem to be any other servants around-but he knew that, with the count, appearances were deceptive.

"There we go." Fosco hefted the assembled machine, which looked something like a large rifle, made primarily of stainless steel, with a bulbous dish at one end and a barrel sporting half a dozen buttons and dials at the other. "As I said, I knew I had to kill Grove and Cutforth in such a way that the police would be utterly baffled. It had to be done with heat, of course. But how? Burning, arson, boiling-much too common. It had to be mysterious, unexplainable. That was when I recalled the phenomenon known as spontaneous human combustion. You know the first documented case of it was here in Italy?"

Pendergast nodded. "The countess Cornelia."

"Countess Cornelia Zangari de' Bandi di Cesena. Most dramatic. How, I wondered, could a similarly devilish effect be duplicated? Then I thought of microwaves ."

"Microwaves?" D'Agosta repeated.

The count smiled patronizingly at him. "Yes, Sergeant. Just like your own microwave oven. They seemed perfect for my needs. Microwaves heat from the inside out. They can be focused, just like light, to-say-burn a body while leaving the rest of the environment intact. Microwaves heat water far more selectively than dry materials, fats, or oils, so they would burn a wet body before heating the rugs or furnishings. And they have an ionizing and heating effect on metals with a certain number of valence electrons."

Fosco ran a hand over his device, then laid it on the table next to him. "As you know, Mr. Pendergast, I'm a tinkerer. I love a challenge. It's quite simple to build a microwave transmitter that would deliver the necessary wattage. The problem was the power supply. But I. G. Farben, a German company which my family was connected with during the War, makes a marvelous combination of capacitor and battery capable of delivering the requisite charge."

D'Agosta glanced at the microwave device. It looked almost silly, like a cheap prop to an old science fiction movie.

"It would never work as a weapon of war: the top theoretical range is less than twenty feet, and it takes time to do its work. But it suited my purposes perfectly. I had quite a time working out the kinks. Many pumpkins were sacrificed, Sergeant D'Agosta. At last, I tested it on that old pedophile in Pistoia-the one whose tomb you examined. There was a bit of a meltdown-the human body takes a lot more heating than a pumpkin. I rebuilt the device with improvements and used it more successfully on the terrorized Grove. It wasn't quite enough to set the man on fire, but it did the job. Then I arranged the scene to my satisfaction, packed up, and left, locking everything and turning the alarm back on. With Cutforth it was even simpler. As I said, my man Pinketts had rented the apartment next door and was undertaking 'renovations.' He made a marvelous elderly English gentleman, poor man, all bent over and muffled up against the chill."

"That explains why they couldn't identify a suspect from the security video cams," D'Agosta said.

"Pinketts used to be in the theater, which frequently comes in handy for my purposes. In any case, the weapon works beautifully through walls made of drywall and wooden studs. Microwaves, my dear Pendergast, have the marvelous property of penetrating drywall like light through glass, as long as there is no moisture or metal. There could of course be no metal nails in the wall between the two apartments, because metal absorbs microwaves and would heat up and cause a fire. So Pinketts opened our side of the wall, removed the nails, and replaced them with wooden dowels. When it was all over, he put our side of the wall back up. The whole operation was disguised as part of the remodeling job. Pinketts himself did the honors on Cutforth while I was at the opera with you. What better alibi than to contrive to spend the evening of the murder with the detective himself!" Fosco heaved in silent mirth.

"And the smell of sulfur?"

"Sulfur burned with phosphorus in a censer, injected through the wall at cracks around the molding."

"How did you burn the images into the wall?"

"The hoofprint in Grove's house was done directly, focusing the microwave. The image in Cutforth's apartment had to be done indirectly-Pinketts couldn't get into the apartment-by focusing the device against a mask. That was a little trickier, but it worked. Burned the image right through the wall. Brilliant, don't you think?"

"You're sick," said D'Agosta.

"I am a tinkerer. I like nothing more than solving tricky little problems." He grinned horribly and picked up the device. "Now please stand back. I need to adjust the range of the beam. It wouldn't do to scorch us as well as the pumpkin."

Fosco raised the ungainly thing, slid its leather strap over his shoulder, aimed it at the pumpkin, adjusted some knobs. Then he pressed a rudimentary kind of trigger. D'Agosta stared in horrified fascination. There was a humming noise in the capacitor-that was all.

"Right now the device is working up from its lowest setting. If that pumpkin were our victim, he would begin to experience a most awful crawling sensation in his guts and over his skin about now."

The pumpkin remained unaffected. Fosco turned a knob, and the humming went up a notch.

"Now our victim is screaming. The crawling sensation has gotten unbearable. I imagine it's like a stomach full of wasps, stinging endlessly. His skin, too, would start to dry and blister. The rising heat within his muscles would soon cause the neurons to begin firing, jerking his limbs spasmodically, causing him to fall down and go into convulsions. His internal temperature is soaring. Within a few more seconds he'll be thrashing on the ground, biting off or swallowing his tongue."

Another tick of the dial. Now a small blister appeared on the skin of the pumpkin. It seemed to soften, sag a bit. A soft pop, and the pumpkin split open from top to bottom, issuing a spurt of steam.

"Now our victim is unconscious, seconds from death."

There was a muffled boiling sound inside the pumpkin, and the fissure widened. With a sudden wet noise, a jet of orange slime forced itself from the split, oozing over the floor in steaming rivulets.

"No comment necessary. By now, our victim is dead. The interesting part, however, is yet to come."

Blisters began swelling all over the surface of the pumpkin, some popping with little puffs of steam, others breaking and weeping orange fluid.

Another tick of the dial.

The pumpkin split afresh, with a second rush of boiling pulp and seeds squeezing out in a hot viscous paste. The pumpkin sagged further and darkened, the stem blackening and smoking; more fluid and seeds oozed from the cracks along with jets of steam. And then suddenly, with a sharp popping sound, the seeds began to explode. The pumpkin seemed to harden, the room filling with the smell of burned pumpkin flesh; then, with a sudden paff! , it burst into flame.

"Ecco! The deed is done. Our victim is on fire. And yet, if you were to place your hand on the stone next to the pumpkin, you would find it barely warm to the touch."

Fosco lowered the device. The pumpkin continued to smolder, a flame licking the stem, sizzling and crackling as it burned, a foul black smoke rising slowly.

"Pinketts?"

The servant, without missing a beat, picked up a bottle of acqua minerale from the dinner table and poured it over the pumpkin. Then he gave the bubbling remains a deft kick into the fire, heaped on a few more sticks, and retired again to the corner.

"Marvelous, don't you think? And yet it's much more dramatic with a human body, I can assure you."

"You're one sick fuck, you know that?" said D'Agosta.

"This man of yours, Pendergast, is beginning to annoy me."

"Clearly a man of many virtues," Pendergast replied. "But I think this has gone on long enough. It is time for us to get to the remaining business at hand."

"Quite, quite."

"I have come here to offer you a deal."

"Naturally." Fosco's lip curled cynically.

Pendergast glanced at the count a moment, his looks unreadable, letting the silence build. "You will write out and sign a confession of all that you have told us tonight, and you will give me that diabolical machine as proof. I will escort you to the carabinieri, who will arrest you. You will be tried for the murders of Locke Bullard and Carlo Vanni, and as an accomplice in the murder of the priest. Italy has no death penalty, and you will probably be released in twenty-five years, at the age of eighty, to live the remainder of your days in peace and quiet-if you manage to survive prison. This is your side of the bargain."

Fosco listened, an incredulous smile developing on his face. "Is that all? And what will you give me in exchange?"

"Your life."

"I wasn't aware my life was in your hands, Mr. Pendergast. It seems to me it's the other way around."

D'Agosta saw a movement out of the corner of his eye. Pinketts had withdrawn a 9mm Beretta and had it trained on them. D'Agosta's hand moved toward his own weapon, unstrapped the keeper.

Pendergast stopped him with a shake of his head. Then he removed an envelope from his pocket. "A letter identical to this one has been placed with Prince Corso Maffei, to be opened in twenty-four hours if I have not returned to reclaim it."

At the name of Maffei, Fosco paled.