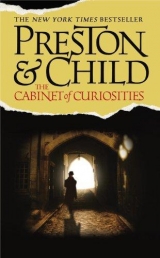

Текст книги "The Cabinet of Curiosities"

Автор книги: Lincoln Child

Соавторы: Douglas Preston

Жанр:

Триллеры

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 23 (всего у книги 29 страниц)

The Search

ONE

NORA WATCHED THE Silver Wraith approach her at an alarming speed, weaving through the Central Park West traffic, red light flashing incongruously on its dashboard. The car screeched to a stop alongside her as the rear door flew open.

“Get in!” called Pendergast.

She jumped inside, the sudden acceleration throwing her back against the white leather of the seat.

Pendergast had lowered the center armrest. He looked straight ahead, his face grimmer than Nora had ever seen it. He seemed to see nothing, notice nothing, as the car tore northward, rocking slightly, bounding over potholes and gaping cracks in the asphalt. To Nora’s right, Central Park raced by, the trees a blur.

“I tried reaching Smithback on his cell phone,” Nora said. “He isn’t answering.”

Pendergast did not reply.

“You really believe Leng’s still alive?”

“I knowso.”

Nora was silent a moment. Then she had to ask. “Do you think—Do you think he’s got Smithback?”

Pendergast did not answer immediately. “The expense voucher Smithback filled out stated he would return the car by five this evening.”

By five this evening . . .Nora felt herself consumed by agitation and panic. Already, Smithback was over six hours overdue.

“If he’s parked near Leng’s house, we might just be able to find him.” Pendergast leaned forward, sliding open the glass panel that isolated the rear compartment. “Proctor, when we reach 131st Street, we’ll be looking for a silver Ford Taurus, New York license ELI-7734, with rental car decals.”

He closed the panel, leaned back against the seat. Another silence fell as the car shot left onto Cathedral Parkway and sped toward the river.

“We would have known Leng’s address in forty-eight hours,” he said, almost to himself. “We were very close. A little more care, a little more method, was all it would have taken. Now, we don’t have forty-eight hours.”

“How much time do we have?”

“I’m afraid we don’t have any,” Pendergast murmured.

TWO

CUSTER WATCHED BRISBANE unlock his office door, open it, then step irritably aside to allow them to enter. Custer stepped through the doorway, the flush of returning confidence adding gravity to his stride. There was no need to hurry; not anymore. He turned, looked around: very clean and modern, lots of chrome and glass. Two large windows looked over Central Park and, beyond, at the twinkling wall of lights that made up Fifth Avenue. His eyes fell to the desk that dominated the center of the room. Antique inkwell, silver clock, expensive knickknacks. And a glass box full of gemstones. Cushy, cushy.

“Nice office,” he said.

Shrugging the compliment aside, Brisbane draped his tuxedo jacket over his chair, then sat down behind the desk. “I don’t have a lot of time,” he said truculently. “It’s eleven o’clock. I expect you to say what you have to say, then have your men vacate the premises until we can determine a mutually agreeable course of action.”

“Of course, of course.” Custer moved about the office, hefting a paperweight here, admiring a picture there. He could see Brisbane growing increasingly irritated. Good. Let the man stew. Eventually, he’d say something.

“Shall we get on with it, Captain?” Brisbane pointedly gestured for Custer to take a seat.

Just as pointedly, Custer continued circling the large office. Except for the knickknacks and the case of gems on the desk and the paintings on the walls, the office looked bare, save for one wall that contained shelving and a closet.

“Mr. Brisbane, I understand you’re the Museum’s general counsel?”

“That’s right.”

“An important position.”

“As a matter of fact, it is.”

Custer moved toward the shelves, examined a mother-of-pearl fountain pen displayed on one of them. “I understand your feelings of invasion here, Mr. Brisbane.”

“That’s reassuring.”

“To a certain extent, you feel it’s your place. You feel protective of the Museum.”

“I do.”

Custer nodded, his gaze moving along the shelf to an antique Chinese snuffbox set with stones. He picked it up. “Naturally, you don’t like a bunch of policemen barging in here.”

“Frankly, I don’t. I’ve told you as much several times already. That’s a very valuable snuffbox, Captain.”

Custer returned it, picked up something else. “I imagine this whole thing’s been rather hard on you. First, there was the discovery of the skeletons left by that nineteenth-century serial killer. Then there was that letter discovered in the Museum’s collections. Very unpleasant.”

“The adverse publicity could have easily harmed the Museum.”

“Then there was that curator—?”

“Nora Kelly.”

Custer noted a new tone creeping into Brisbane’s voice: dislike, disapproval, perhaps a sense of injury.

“The same one who found the skeletons—and the hidden letter, correct? You didn’t like her working on this case. Worried about adverse publicity, I suppose.”

“I thought she should be doing her research. That’s what she was being paid to do.”

“You didn’t want her helping the police?”

“Naturally, I wanted her to do what she could to help the police. I just didn’t want her neglecting her museum duties.”

Custer nodded sagely. “Of course. And then she was chased in the Archives, almost killed. By the Surgeon.” He moved to a nearby bookshelf. The only books it contained were half a dozen fat legal tomes. Even their bindings managed to look stultifyingly dull. He tapped his finger on a spine. “You’re a lawyer?”

“ General counselusually means lawyer.”

This bounced off Custer without leaving a dent. “I see. Been here how long?”

“A little over two years.”

“Like it?”

“It’s a very interesting place to work. Now look, I thought we were going to talk about getting your men out of here.”

“Soon.” Custer turned. “Visit the Archives much?”

“Not so much. More, lately, of course, with all the activity.”

“I see. Interesting place, the Archives.” He turned briefly to see the effect of this observation on Brisbane. The eyes. Watch the eyes.

“I suppose some find it so.”

“But not you.”

“Boxes of paper and moldy specimens don’t interest me.”

“And yet you visited there”—Custer consulted his notebook—“let’s see, no less than eight times in the last ten days.”

“I doubt it was that often. On Museum business, in any case.”

“In any case.” He looked shrewdly back at Brisbane. “The Archives. Where the body of Puck was found. Where Nora Kelly was chased.”

“You mentioned her already.”

“And then there’s Smithback, that annoying reporter?”

“Annoying is an understatement.”

“Didn’t want him around, did you? Well, who would?”

“My thinking exactly. You’ve heard, of course, how he impersonated a security officer? Stole Museum files?”

“I’ve heard, I’ve heard. Fact is, we’re looking for the man, but he seems to have disappeared. You wouldn’t know where he was, by any chance, would you?” He added a faint emphasis to this last phrase.

“Of course not.”

“Of course not.” Custer returned his attention to the gems. He stroked the glass case with a fat finger. “And then there’s that FBI agent, Pendergast. The one who was attacked. Also very annoying.”

Brisbane remained silent.

“Didn’t much like him around either—eh, Mr. Brisbane?”

“We had enough policemen crawling over the place. Why compound it with the FBI? And speaking of policemen crawling around—”

“It’s just that I find it very curious, Mr. Brisbane . . .” Custer let the sentence trail off.

“What do you find curious, Captain?”

There was a commotion in the hallway outside, then the door opened abruptly. A police sergeant entered, dusty, wide-eyed, sweating.

“Captain!” he gasped. “We were interviewing this woman just now, a curator, and she locked—”

Custer looked at the man—O’Grady, his name was—reprovingly. “Not now, Sergeant. Can’t you see I’m conducting a conversation here?”

“But—”

“You heardthe captain,” Noyes interjected, propelling the protesting sergeant toward the door.

Custer waited until the door closed again, then turned back to Brisbane. “I find it curious how very interestedyou’ve been in this case,” he said.

“It’s my job.”

“I know that. You’re a very dedicated man. I’ve also noticed your dedication in human resources matters. Hiring, firing . . .”

“That’s correct.”

“Reinhart Puck, for example.”

“What about him?”

Custer consulted his notebook again. “Why exactly didyou try to fire Mr. Puck, just two days before his murder?”

Brisbane started to say something, then hesitated. A new thought seemed to have occurred to him.

“Strange timing there, wouldn’t you agree, Mr. Brisbane?”

The man smiled thinly. “Captain, I felt the position was extraneous. The Museum is having financial difficulties. And Mr. Puck had been . . . well, he had not been cooperative. Of course, it had nothing to do with the murder.”

“But they wouldn’t let you fire him, would they?”

“He’d been with the Museum over twenty-five years. They felt it might affect morale.”

“Must’ve made you angry, being shot down like that.”

Brisbane’s smile froze in place. “Captain, I hope you’re not suggesting Ihad anything to do with the murder.”

Custer raised his eyebrows in mock astonishment. “Am I?”

“Since I assume you’re asking a rhetorical question, I won’t bother to answer it.”

Custer smiled. He didn’t know what a rhetorical question was, but he could see that his questions were finding their mark. He gave the gem case another stroke, then glanced around. He’d covered the office; all that remained was the closet. He strolled over, put his hand on the handle, paused.

“But it didmake you angry? Being contradicted like that, I mean.”

“No one is pleased to be countermanded,” Brisbane replied icily. “The man was an anachronism, his work habits clearly inefficient. Look at that typewriter he insisted on using for all his correspondence.”

“Yes. The typewriter. The one the murderer used to write one—make that two—notes. You knew about that typewriter, I take it?”

“Everybody did. The man was infamous for refusing to allow a computer terminal on his desk, refusing to use e-mail.”

“I see.” Custer nodded, opened the closet.

As if on cue, an old-fashioned black derby hat fell out, bounced across the floor, and rolled in circles until it finally came to rest at Custer’s feet.

Custer looked down at it in astonishment. It couldn’t have happened more perfectly if this had been an Agatha Christie murder mystery. This kind of thing just didn’t happen in real policework. He could hardly believe it.

He looked up at Brisbane, his eyebrows arching quizzically.

Brisbane looked first confounded, then flustered, then angry.

“It was for a costume party at the Museum,” the lawyer said. “You can check for yourself. Everyone saw me in it. I’ve had it for years.”

Custer poked his head into the closet, rummaged around, and removed a black umbrella, tightly furled. He brought it out, stood it up on its point, then released it. The umbrella toppled over beside the hat. He looked up again at Brisbane. The seconds ticked on.

“This is absurd!” exploded Brisbane.

“I haven’t said anything,” said Custer. He looked at Noyes. “Did yousay anything?”

“No, sir, I didn’t say anything.”

“So what exactly, Mr. Brisbane, is absurd?”

“What you’re thinking—” The man could hardly get out the words. “That I’m . . . that, you know . . . Oh, this is perfectly ridiculous!”

Custer placed his hands behind his back. He came forward slowly, one step after another, until he reached the desk. And then, very deliberately, he leaned over it.

“What amI thinking, Mr. Brisbane?” he asked quietly.

THREE

THE ROLLS ROCKETED up Riverside, their driver weaving expertly through the lines of traffic, threading the big vehicle through impossibly narrow gaps, sometimes forcing opposing cars onto the curb. It was after eleven P.M., and the traffic was beginning to thin out. But the curbs of Riverside and the side streets that led away from it remained completely jammed with parked cars.

The car swerved onto 131st Street, slowing abruptly. And almost immediately—no more than half a dozen cars in from Riverside—Nora spotted it: a silver Ford Taurus, New York plate ELI-7734.

Pendergast got out, walked over to the parked car, leaned toward the dashboard to verify the VIN. Then he moved around to the passenger door and broke the glass with an almost invisible jab. The alarm shrieked in protest while he searched the glove compartment and the rest of the interior. In a moment he returned.

“The car’s empty,” he told Nora. “He must have taken the address with him. We’ll have to hope Leng’s house is close by.”

Telling Proctor to park at Grant’s Tomb and wait for their call, Pendergast led the way down 131st in long, sweeping strides. Within moments they reached the Drive itself. Riverside Park stretched away across the street, its trees like gaunt sentinels at the edge of a vast, unknown tract of darkness. Beyond the park was the Hudson, glimmering in the vague moonlight.

Nora looked left and right, at the countless blocks of decrepit apartment buildings, old abandoned mansions, and squalid welfare hotels that stretched in both directions. “How are we going to find it?” she asked.

“It will have certain characteristics,” Pendergast replied. “It will be a private house, at least a hundred years old, not broken into apartments. It will probably look abandoned, but it will be very secure. We’ll head south first.”

But before proceeding, he stopped and placed a hand on her shoulder. “Normally, I’d never allow a civilian along on a police action.”

“But that’s my boyfriend caught—”

Pendergast raised his hand. “We have no time for discussion. I have already considered carefully what it is we face. I’m going to be as blunt as possible. If we do find Leng’s house, the chances of my succeeding without assistance are very small.”

“Good. I wouldn’t let you leave me behind, anyway.”

“I know that. I also know that, given Leng’s cunning, two people have a better chance of success than a large—and loud—official response. Even if we could get such a response in time. But I must tell you, Dr. Kelly, I am bringing you into a situation where there are an almost infinite number of unknown variables. In short, it is a situation in which it is very possible one or both of us may be killed.”

“I’m willing to take that risk.”

“One final comment, then. In my opinion, Smithback is already dead, or will be by the time we find the house, get inside, and secure Leng. This rescue operation is already, therefore, a probable failure.”

Nora nodded, unable to reply.

Without another word, Pendergast turned and began to walk south.

They passed several old houses clearly broken into apartments, then a welfare hotel, the resident alcoholics watching them apathetically from the steps. Next came a long row of sordid tenements.

And then, at Tiemann Place, Pendergast paused before an abandoned building. It was a small townhouse, its windows boarded over, the buzzer missing. He stared up at it briefly, then went quickly around to the side, peered over a broken railing, returned.

“What do you think?” Nora whispered.

“I think we go in.”

Two heavy pieces of plywood, chained shut, covered the opening where the door had been. Pendergast grasped the lock on the chain. A white hand slid into his suit jacket and emerged, holding a small device with toothpick-like metal attachments projecting from one end. It gleamed in the reflected light of the street lamp.

“What’s that?” Nora asked.

“Electronic lockpick,” Pendergast replied, fitting it to the padlock. The latch sprung open in his long white hands. He pulled the chain away from the plywood and ducked inside, Nora following.

A noisome stench welled out of the darkness. Pendergast pulled out his flashlight and shined the beam over a blizzard of decay: rotting garbage, dead rats, exposed lath, needles and crack vials, standing puddles of rank water. Without a word he turned and exited, Nora following.

They worked their way down as far as 120th Street. Here, the neighborhood improved and most of the buildings were occupied.

“There’s no point in going farther,” Pendergast said tersely. “We’ll head north instead.”

They hurried back to 131st Street—the point where their search had begun—and continued north. This proved much slower going. The neighborhood deteriorated until it seemed as if most of the buildings were abandoned. Pendergast dismissed many out of hand, but he broke into one, then another, then a third, while Nora watched the street.

At 136th Street they stopped before yet another ruined house. Pendergast looked toward it, scrutinizing the facade, then turned his eyes northward, silent and withdrawn. He was pale; the activity had clearly taxed his weakened frame.

It was as if the entire Drive, once lined with elegant townhouses, was now one long, desolate ruin. It seemed to Nora that Leng could be in any one of those houses.

Pendergast dropped his eyes toward the ground. “It appears,” he said in a low voice, “that Mr. Smithback had difficulty finding parking.”

Nora nodded, feeling a rising despair. The Surgeon now had Smithback at least six hours, perhaps several more. She would not follow that train of thought to its logical conclusion.

FOUR

CUSTER ALLOWED BRISBANE to stew for a minute, then two. And then he smiled—almost conspiratorially—at the lawyer. “Mind if I . . . ?” he began, nodding toward the bizarre chrome-and-glass chair before Brisbane’s desk.

Brisbane nodded. “Of course.”

Custer sank down, trying to maneuver his bulk into the most comfortable position the chair would allow. Then he smiled again. “Now, you were about to say something?” He hiked a pant leg, tried to throw it over the other, but the weird angle of the chair knocked it back against the floor. Unruffled, he cocked his head, raising an eyebrow quizzically across the desk.

Brisbane’s composure had returned. “Nothing. I just thought, with the hat . . .”

“What?”

“Nothing.”

“In that case, tell me about the Museum’s costume party.”

“The Museum often throws fund-raisers. Hall openings, parties for big donors, that sort of thing. Once in a while, it’s a costume ball. I always wear the same thing. I dress like an English banker on his way to the City. Derby hat, pinstriped pants, cutaway.”

“I see.” Custer glanced at the umbrella. “And the umbrella?”

“Everybody owns a black umbrella.”

A veil had dropped over the man’s emotions. Lawyer’s training, no doubt.

“How long have you owned the hat?”

“I already told you.”

“And where did you buy it?”

“Let’s see . . . at an old antique shop in the Village. Or perhaps TriBeCa. Lispinard Street, I believe.”

“How much did it cost?”

“I don’t remember. Thirty or forty dollars.” For a moment, Brisbane’s composure slipped ever so slightly. “Look, why are you so interested in that hat? A lot of people own derby hats.”

Watch the eyes.And the eyes looked panicked. The eyes looked guilty.

“Really?” Custer replied in an even voice. “A lot of people? The only person I know who owns a derby hat in New York City is the killer.”

This was the first mention of the word “killer,” and Custer gave it a slight, but noticeable, emphasis. Really, he was playing this beautifully, like a master angler bringing in a huge trout. He wished this was being captured on video. The chief would want to see it, perhaps make it available as a training film for aspiring detectives. “Let’s get back to the umbrella.”

“I bought it . . . I can’t remember. I’m always buying and losing umbrellas.” Brisbane shrugged casually, but his shoulders were stiff.

“And the rest of your costume?”

“In the closet. Go ahead, take a look.”

Custer had no doubt the rest of the costume would match the description of a black, old-fashioned coat. He ignored the attempted distraction. “Where did you buy it?”

“I think I found the pants and coat at that used formalwear shop near Bloomingdale’s. I just can’t think of the name.”

“No doubt.” Custer glanced searchingly at Brisbane. “Odd choice for a costume party, don’t you think? English banker, I mean.”

“I dislike looking ridiculous. I’ve worn that costume half a dozen times to Museum parties, you can check with anyone. I put that costume to good use.”

“Oh, I have no doubt you put it to good use. Good use indeed.” Custer glanced over at Noyes. The man was excited, a kind of hungry, almost slavering look on his face. He, at least, realized what was coming.

“Where were you, Mr. Brisbane, on October 12, between eleven o’clock in the evening and four o’clock the following morning?” This was the time bracket the coroner had determined during which Puck had been killed.

Brisbane seemed to think. “Let’s see . . . It’s hard to remember.” He laughed again.

Custer laughed, too.

“I can’t remember what I did that night. Not precisely. After twelve or one, I would have been in bed, of course. But before then . . . Yes, I remember now. I was at home that night. Catching up on my reading.”

“And you live alone, Mr. Brisbane?”

“Yes.”

“So you have no one who can vouch for you being at home? A landlady, perhaps? Girlfriend? Boyfriend?”

Brisbane frowned. “No. No, nothing like that. So, if it’s all the same to you—”

“One moment, Mr. Brisbane. And where did you say you live?”

“I didn’t say. Ninth Street, near University Place.”

“Hmmm. No more than a dozen blocks from Tompkins Square Park. Where the second murder took place.”

“That’s a very interesting coincidence, no doubt.”

“It is.” Custer glanced out the windows, where Central Park lay beneath a mantle of darkness. “And no doubt it’s a coincidence that the firstmurder took place right out there, in the Ramble.”

Brisbane’s frown deepened. “Really, Detective, I think we’ve reached the point where questions end and speculation begins.” He pushed back his chair, prepared to stand up. “And now, if you don’t mind, I’d like to get on with the business of clearing your men out of this Museum.”

Custer made a suppressing motion with one hand, glanced again at Noyes. Get ready.“There’s just one other thing. The thirdmurder.” He slid a piece of paper out of his notebook with a nonchalant motion. “Do you know an Oscar Gibbs?”

“Yes, I believe so. Mr. Puck’s assistant.”

“Exactly. According to the testimony of Mr. Gibbs, on the afternoon of October 12, you and Mr. Puck had a little, ah, discussionin the Archives. This was after you found out that Human Resources had not supported your recommendation to fire Puck.”

Brisbane colored slightly. “I wouldn’t believe everything you hear.”

Custer smiled. “I don’t, Mr. Brisbane. Believe me, I don’t.” He followed this with a long, delicious pause. “Now, this Mr. Oscar Gibbs said that you and Puck were yelling at each other. Or rather, you were yelling at Puck. Care to tell me, in yourwords, what that was about?”

“I was reprimanding Mr. Puck.”

“What for?”

“Neglecting my instructions.”

“Which were?”

“To stick to his job.”

“To stickto his job. How had he been deviating from his job?”

“He was doing outside work, helping Nora Kelly with her external projects, when I had specifically—”

It was time. Custer pounced.

“According to Mr. Oscar Gibbs, you were (and I will read): screaming and yelling and threatening to bury Mr. Puck. He(that’s you, Mr. Brisbane) said he wasn’t through by a long shot.”Custer lowered the paper, glanced at Brisbane. “That’s the word you used: ‘ bury.’ ”

“It’s a common figure of speech.”

“And then, not twenty-four hours later, Puck’s body was found, gored on a dinosaur in the Archives. After having been butchered, most likely in those very same Archives. An operation like that takes time, Mr. Brisbane. Clearly, it was done by somebody who knew the Museum’s ways very well. Someone with a security clearance. Someone who could move around the Museum without exciting notice. An insider, if you will. And then, Nora Kelly gets a phony note, typed on Puck’s typewriter, asking her to come down—and she herself is attacked, pursued with deadly intent. Nora Kelly.The other thorn in your side. The third thorn, the FBI agent, was in the hospital at this point, having been attacked by someone wearing a derby hat.”

Brisbane stared at him in disbelief.

“Why didn’t you want Puck to help Nora Kelly in her—what did you call them– externalprojects?”

This was answered by silence.

“What were you afraid she would find? Theywould find?”

Brisbane’s mouth worked briefly. “I . . . I . . .”

Now Custer slipped in the knife. “Why the copycat angle, Mr. Brisbane? Was it something you found in the Archives? Is thatwhat prompted you to do it? Was Puck getting too close to learning something?”

At this, Brisbane found his voice at last. He shot to his feet. “Now, just a minute—”

Custer turned. “Officer Noyes?”

“Yes?” Noyes responded eagerly.

“Cuff him.”

“No,”Brisbane gasped. “You fool, you’re making a terrible mistake—”

Custer worked his way out of the chair—it was not as smooth a motion as he would have wished—and began abruptly booming out the Miranda rights: “You have the right to remain silent—”

“This is an outrage—”

“—you have the right to an attorney—”

“I will not accept this!”

“—you have the right—”

He thundered it out to the bitter end, overriding Brisbane’s protestations. He watched as the gleeful Noyes slapped the cuffs on the man. It was the most satisfying collar Custer could ever remember. It was, in fact, the single greatest job of police work he had done in his life. This was the stuff of legend. For many years to come, they’d be telling the story of how Captain Custer put the cuffs on the Surgeon.

FIVE

PENDERGAST SET OFF up Riverside once again, black suit coat open and flapping behind him in the Manhattan night. Nora hurried after. Her thoughts returned to Smithback, imprisoned in one of these gaunt buildings. She tried to force the image from her mind, but it kept returning, again and again. She was almost physically sick with worry about what might be happening—what might have alreadyhappened.

She wondered how she could have been so angry with him. It’s true that much of the time he was impossible—a schemer, impulsive, always looking for an angle, always getting himself into trouble. And yet many of those same negative qualities were his most endearing. She thought back to how he’d dressed up as a bum to help her retrieve the old dress from the excavation; how he’d come to warn her after Pendergast was stabbed. When push came to shove, he was there. She had been awfully hard on him. But it was too late to be sorry. She suppressed a sob of bitter regret.

They moved past guttered mansions and once elegant townhouses, now festering crack dens and shooting galleries for junkies. Pendergast gave each building a searching look, always turning away with a little shake of his head.

Nora’s thoughts flitted briefly to Leng himself. It seemed impossible that he could still be alive, concealed within one of these crumbling dwellings. She glanced up the Drive again. She had to concentrate, try to pick his house out from the others. Wherever he lived, it would be comfortable. A man who had lived over a hundred and fifty years would be excessively concerned with comfort. But it would no doubt give the surface impression of being abandoned. And it would be well-nigh impregnable—Leng wouldn’t want any unexpected visitors. This was the perfect neighborhood for such a place: abandoned, yet once elegant; externally shabby, yet livable inside; boarded up; very private.

The trouble was, so many of the buildings met those criteria.

Then, near the corner of 138th Street, Pendergast stopped dead. He turned, slowly, to face yet another abandoned building. It was a large, decayed mansion, a hulking shadow of bygone glory, set back from the street by a small service drive. Like many others, the first floor had been securely boarded up with tin. It looked just like a dozen other buildings they had passed. And yet Pendergast was staring at it with an expression of intentness Nora had not seen before.

Silently, he turned the corner of 138th Street. Nora followed, watching him. The FBI agent moved slowly, eyes mostly on the ground, with just occasional darted glances up at the building. They continued down the block until they reached the corner of Broadway. The moment they turned the corner, Pendergast spoke.

“That’s it.”

“How do you know?”

“The crest carved on the escutcheon over the door. Three apothecary balls over a sprig of hemlock.” He waved his hand. “Forgive me if I reserve explanations for later. Follow my lead. And be very, very careful.”

He continued around the block until they reached the corner of Riverside Drive and 137th. Nora looked at the building with a mixture of curiosity, apprehension, and outright fear. It was a large, four-story, brick-and-stone structure that occupied the entire short block. Its frontage was enclosed in a wrought iron fence, ivy covering the rusty pointed rails. The garden within was long gone, taken over by weeds, bushes, and garbage. A carriage drive circled the rear of the house, exiting on 138th Street. Though the lower windows were securely boarded over, the upper courses remained unblocked, although at least one window on the second story was broken. She stared up at the crest Pendergast had mentioned. An inscription in Greek ran around its edge.

A gust of wind rustled the bare limbs in the yard; the reflected moon, the scudding clouds, flickered in the glass panes of the upper stories. The place looked haunted.

Pendergast ducked into the carriage drive, Nora following close behind. The agent kicked aside some garbage with his shoe and, after a quick look around, stepped up to a solid oak door set into deep shadow beneath the porte-cochère. It seemed to Nora as if Pendergast merely caressed the lock; and then the door opened silently on well-oiled hinges.

They stepped quickly inside. Pendergast eased the door closed, and Nora heard the sound of a lock clicking. A moment of intense darkness while they stood still, listening for any sounds from within. The old house was silent. After a minute, the yellow line of Pendergast’s hooded flashlight appeared, scanning the room around them.

They were standing in a small entryway. The floor was polished marble, and the walls were papered in heavy velvet fabric. Dust covered everything. Pendergast stood still, directing his light at a series of footprints—some shod, some stockinged—that had disturbed the dust on the floor. He looked at them for so long, studying them as an art student studies an old master, that Nora felt impatience begin to overwhelm her. At last he led the way, slowly, through the room and down a short passage leading into a large, long hall. It was paneled in a very rich, dense wood, and the low ceiling was intricately worked, a blend of the gothic and austere.

![Книга Legendary Moonlight Sculptor [Volume 1][Chapter 1-3] автора Nam Heesung](http://itexts.net/files/books/110/oblozhka-knigi-legendary-moonlight-sculptor-volume-1chapter-1-3-145409.jpg)