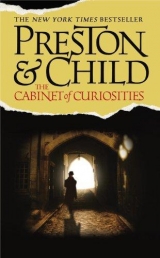

Текст книги "The Cabinet of Curiosities"

Автор книги: Lincoln Child

Соавторы: Douglas Preston

Жанр:

Триллеры

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 17 (всего у книги 29 страниц)

“Ninety-two dollars!” O’Shaughnessy cried. “How many drinks did you have before I arrived?”

“The good things in life, Patrick, are not free,” Smithback said mournfully. “That is especially true of single malt Scotch.”

“Think of the poor starving children.”

“Think of the poor thirsty journalists. Next time, you pay. Especially if you come armed with a story that crazy.”

“I told you so. And I hope you won’t mind drinking Powers. No Irishman would be caught dead paying a tab like that. Only a Scotsman would dare charge that much for a drink.”

Smithback turned onto Columbus Avenue, thinking. Suddenly, he stopped. While Pendergast’s theory was ridiculous, it had given him an idea. With all the excitement about the copycat killings and the Doyers Street find, no one had really followed up on Leng himself. Who was he? Where did he come from? Where did he get his medical degree? What was his connection to the Museum? Where had he lived?

Now this was good.

A story on Dr. Enoch Leng, mass murderer. Yes, yes, this was it. This might just be the thing to save his ass at the Times.

Come to think of it, this was better than good. This guy antedated Jack the Ripper. Enoch Leng: A Portrait of America’s First Serial Killer.This could be a cover story for the Times Sunday Magazine.He’d kill two birds with one stone: do the research he’d promised O’Shaughnessy, while getting background on Leng. And he wouldn’t be betraying any confidences, of course—because once he’d determined when the man died, that would be the end of Pendergast’s crazy theory.

He felt a sudden shiver of fear. What if Harriman was already pursuing the story of Leng? He’d better get to work right away. At least he had one big advantage over Harriman: he was a hell of a researcher. He’d start with the newspaper morgue—look for little notes, mentions of Leng or Shottum or McFadden. And he’d look for more killings with the Leng modus operandi: the signature dissection of the spinal cord. Surely Leng had killed more people than had been found at Catherine and Doyers Streets. Perhaps some of those other killings had come to light and made the papers.

And then there were the Museum’s archives. From his earlier book projects, he’d come to know them backward and forward. Leng had been associated with the Museum. There would be a gold mine of information in there, if only one knew where to find it.

And there would be a side benefit: he might just be able to pass along to Nora the information she wanted about where Leng lived. A little gesture like that might get their relationship back on track. And who knows? It might get Pendergast’s investigation back on track, as well.

His meeting with O’Shaughnessy hadn’t been a total loss, after all.

TWO

EAST TWELFTH STREET was a typical East Village street,O’Shaughnessy thought as he turned the corner from Third Avenue: a mixture of punks, would-be poets, ’60s relics, and old-timers who just didn’t have the energy or money to move. The street had improved a bit in recent years, but there was still a superfluity of beaten-down tenements among the head shops, wheat-grass bars, and used-record vendors. He slowed his pace, watching the people passing by: slumming tourists trying to look cool; aging punk rockers with very dated spiked purple hair; artists in paint-splattered jeans lugging canvases; drugged-out skinheads in leather with dangling chrome doohickeys. They seemed to give him a wide berth: nothing stood out on a New York City street quite like a plainclothes police officer, even one on administrative leave and under investigation.

Up ahead now, he could make out the shop. It was a little hole-in-the-wall of black-painted brick, shoehorned between brownstones that seemed to sag under the weight of innumerable layers of graffiti. The windows of the shop were thick with dust, and stacked high with ancient boxes and displays, so faded with age and sun that their labels were indecipherable. Small greasy letters above the windows spelled out New Amsterdam Chemists.

O’Shaughnessy paused, examining the shopfront. It seemed hard to believe that an old relic like this could survive, what with a Duane Reade on the very next corner. Nobody seemed to be going in or out. The place looked dead.

He stepped forward again, approaching the door. There was a buzzer, and a small sign that read Cash Only.He pressed the buzzer, hearing it rasp far, far within. For what seemed a long time, there was no other noise. Then he heard the approach of shuffling footsteps. A lock turned, the door opened, and a man stood before him. At least, O’Shaughnessy thought it was a man: the head was as bald as a billiard ball, and the clothes were masculine, but the face had a kind of strange neutrality that made sex hard to determine.

Without a word, the person turned and shuffled away again. O’Shaughnessy followed, glancing around curiously. He’d expected to find an old pharmacy, with perhaps an ancient soda fountain and wooden shelves stocked with aspirin and liniment. Instead, the shop was an incredible rat’s nest of stacked boxes, spiderwebs, and dust. Stifling a cough, O’Shaughnessy traced a complex path toward the back of the store. Here he found a marble counter, scarcely less dusty than the rest of the shop. The person who’d let him in had taken up a position behind it. Small wooden boxes were stacked shoulder high on the wall behind the shopkeeper. O’Shaughnessy squinted at the paper labels slid into copper placards on each box: amaranth, nux vomica, nettle, vervain, hellebore, nightshade, narcissus, shepherd’s purse, pearl trefoil. On an adjoining wall were hundreds of glass beakers, and beneath were several rows of boxes, chemical symbols scrawled on their faces in red marker. A book titled Wortcunninglay on the counter.

The man—it seemed easiest to think of him as a man—stared back at O’Shaughnessy, pasty face expectant.

“O’Shaughnessy, FBI consultant,” O’Shaughnessy said, displaying the identity card Pendergast had secured for him. “I’d like to ask you a few questions, if I might.”

The man scrutinized the card, and for a minute O’Shaughnessy thought he was going to challenge it. But the shopkeeper merely shrugged.

“What kind of people visit your shop?”

“It’s mostly those wiccans.” The man screwed up his face.

“Wiccans?”

“Yeah. Wiccans. That’s what they call themselves these days.”

Abruptly, O’Shaughnessy understood. “You mean witches.”

The man nodded.

“Anybody else? Any, say, doctors?”

“No, nobody like that. We get chemists here, too. Sometimes hobbyists. Health supplement types.”

“Anybody who dresses in an old-fashioned, or unusual fashion?”

The man gestured in the vague direction of East Twelfth Street. “They alldress in an unusual fashion.”

O’Shaughnessy thought for a moment. “We’re investigating some old crimes that took place near the turn of the century. I was wondering if you’ve got any old records I could examine, lists of clientele and the like.”

“Maybe,” the man said. The voice was high, very breathy.

This answer took O’Shaughnessy by surprise. “What do you mean?”

“The shop burned to the ground in 1924. After it was rebuilt, my grandfather—he was running the place back then—started keeping his records in a fireproof safe. After my father took over, he didn’t use the safe much. In fact, he only used it for storing some possessions of my grandfather’s. He passed away three months ago.”

“I’m sorry to hear that,” O’Shaughnessy said. “How did he die?”

“Stroke, they said. So anyway, a few weeks later, an antiques dealer came by. Looked around the shop, bought a few old pieces of furniture. When he saw the safe, he offered me a lot of money if there was anything of historical value inside. So I had it drilled.” The man sniffed. “But there was nothing much. Tell the truth, I’d been hoping for some gold coins, maybe old securities or bonds. The fellow went away disappointed.”

“So what was inside?”

“Papers. Ledgers. Stuff like that. That’s why I told you, maybe.”

“Can I have a look at this safe?”

The man shrugged. “Why not?”

The safe stood in a dimly lit back room, amid stacks of musty boxes and decaying wooden crates. It was shoulder high, made of thick green metal. There was a shiny cylindrical hole where the lock mechanism had been drilled out.

The man pulled the door open, then stepped back as O’Shaughnessy came forward. He knelt and peered inside. Dust motes hung like a pall in the air. The contents of the safe lay in deep shadow.

“Can you turn on some more lights?” O’Shaughnessy asked.

“Can’t. Aren’t any more.”

“Got a flashlight handy?”

The man shook his head. “But hold on a second.” He shuffled away, then returned a minute later, carrying a lighted taper in a brass holder.

Jesus, this is unbelievable,O’Shaughnessy thought. But he accepted the candle with murmured thanks and held it inside the safe.

Considering its large size, the safe was rather empty. O’Shaughnessy moved the candle around, making a mental inventory of its contents. Stacks of old newspapers in one corner; various yellowed papers, tied into small bundles; several rows of ancient-looking ledger books; two more modern-looking volumes, bound in garish red plastic; half a dozen shoe boxes with dates scrawled on their faces.

Setting the candle on the floor of the safe, O’Shaughnessy grabbed eagerly at the old ledgers. The first one he opened was simply a shop inventory, for the year 1925: page after page of items, written in a spidery hand. The other volumes were similar: semiannual inventories, ending in 1942.

“When did your father take over the shop?” O’Shaughnessy asked.

The man thought for a moment. “During the war. ’41 maybe, or ’42.”

Makes sense,O’Shaughnessy thought. Replacing the ledgers, he flipped through the stack of newspapers. He found nothing but a fresh cloud of dust.

Moving the candle to one side, and fighting back a rising sense of disappointment, he reached for the bundles of papers. These were all bills and invoices from wholesalers, covering the same period: 1925 to 1942. No doubt they would match the inventory ledgers.

The red plastic volumes were clearly far too recent to be of any interest. That left just the shoe boxes. One more chance.O’Shaughnessy plucked a shoe box from the top of the pile, blew the dust from its lid, opened it.

Inside were old tax returns.

Damn it,O’Shaughnessy thought as he replaced the box. He chose another at random, opened the lid. More returns.

O’Shaughnessy sat back on his haunches, candle in one hand and shoe box in the other. No wonder the antiques dealer left empty-handed,he thought. Oh, well. It was worth a try.

With a sigh, he leaned forward to replace the box. As he did so, he glanced once again at the red plastic folders. It was strange: the man said his father only used the safe for storing things of the grandfather. But plastic was a recent invention, right? Surely later than 1942. Curious, he plucked up one of the volumes and flipped it open.

Within, he saw a dark-ruled page, full of old, handwritten entries. The page was sooty, partially burned, its edges crumbling away into ash.

He glanced around. The proprietor of the shop had moved away, and was rummaging inside a cardboard box.

Eagerly O’Shaughnessy snatched both the plastic volume and its mate from the safe. Then he blew out the candle and stood up.

“Nothing much of interest, I’m afraid.” He held up the volumes with feigned nonchalance. “But as a formality, I’d like to take these down to our office, just for a day or two. With your permission, of course. It’ll save you and me lots of paperwork, court orders, all that kind of thing.”

“Court orders?” the man said, a worried expression coming over his face. “Sure, sure. Keep them as long as you want.”

Outside on the street, O’Shaughnessy paused to brush dust from his shoulders. Rain was threatening, and lights were coming on in the shotgun flats and coffeehouses that lined the street. A peal of distant thunder sounded over the hum of traffic. O’Shaughnessy turned up the collar of his jacket and tucked the volumes carefully under one arm as he hurried off toward Third Avenue.

From the opposite sidewalk, in the shadow of a brownstone staircase, a man watched O’Shaughnessy depart. Now he came forward, derby hat low over a long black coat, cane tapping lightly on the sidewalk, and—after looking carefully left and right—slowly crossed the street, in the direction of New Amsterdam Chemists.

THREE

BILL SMITHBACK LOVED the New York Times newspaper morgue: a tall, cool room with rows of metal shelves groaning under the weight of leather-bound volumes. On this particular morning, the room was completely empty. It was rarely used anymore by other reporters, who preferred to use the digitized, online editions, which went back only twenty-five years. Or, if necessary, the microfilm machines, which were a pain but relatively fast. Still, Smithback found there was nothing more interesting, or so curiously useful, as paging through the old numbers themselves. You often found little strings of information in successive issues—or on adjoining pages—that you would have missed by cranking through reels of microfilm at top speed.

When he proposed to his editor the idea of a story on Leng, the man had grunted noncommittally—a sure sign he liked it. As he was leaving, he heard the bug-eyed monster mutter: “Just make damn sure it’s better than that Fairhaven piece, okay? Something with marrow.”

Well, it would be better than Fairhaven. It hadto be.

It was afternoon by the time he settled into the morgue. The librarian brought him the first of the volumes he’d requested, and he opened it with reverence, inhaling the smell of decaying wood pulp, old ink, mold, and dust. The volume was dated January 1881, and he quickly found the article he was looking for: the burning of Shottum’s cabinet. It was a front-page story, with a handsome engraving of the flames. The article mentioned that the eminent Professor John C. Shottum was missing and feared dead. Also missing, the article stated, was a man named Enoch Leng, who was vaguely billed as a boarder at the cabinet and Shottum’s “assistant.” Clearly, the writer knew nothing about Leng.

Smithback paged forward until he found a follow-up story on the fire, reporting that remains believed to be Shottum had been found. No mention was made of Leng.

Now working backward, Smithback paged through the city sections, looking for articles on the Museum, the Lyceum, or any mention of Leng, Shottum, or McFadden. It was slow going, and Smithback often found himself sidetracked by various fascinating, but unrelated, articles.

After a few hours, he began to get a little nervous. There were plenty of articles on the Museum, a few on the Lyceum, and even occasional mentions of Shottum and his colleague, Tinbury McFadden. But he could find nothing at all on Leng, except in the reports of the meetings of the Lyceum, where a “Prof. Enoch Leng” was occasionally listed among the attendees. Leng clearly kept a low profile.

This is going nowhere, fast,he thought.

He launched into a second line of attack, which promised to be much more difficult.

Starting in 1917, the date that Enoch Leng abandoned his Doyers Street laboratory, Smithback began paging forward, looking for any murders that fit the profile. There were 365 editions of the Timesevery year. In those days, murders were a rare enough occurrence to usually land on the front page, so Smithback confined himself to perusing the front pages—and the obituaries, looking for the announcement of Leng’s death which would interest O’Shaughnessy as well as himself.

There were many murders to read about, and a number of highly interesting obituaries, and Smithback found himself fascinated—too fascinated. It was slow going.

But then, in the September 10, 1918, edition, he came across a headline, just below the fold: Mutilated Body in Peck Slip Tenement.The article, in an old-fashioned attempt to preserve readers’ delicate sensibilities, did not go into detail about what the mutilations were, but it appeared to involve the lower back.

He read on, all his reporter’s instincts aroused once again. So Leng was still active, still killing, even after he abandoned his Doyers Street lab.

By the end of the day he had netted a half-dozen additional murders, about one every two years, that could be the work of Leng. There might have been others, undiscovered; or it might be that Leng had stopped hiding the bodies and was simply leaving them in tenements in widely scattered sections of the city. The victims were always homeless paupers. In only one case was the body even identified. They had all been sent to Potter’s Field for burial. As a result, nobody had remarked on the similarities. The police had never made the connection among them.

The last murder with Leng’s modus operandi seemed to occur in 1935. After that, there were plenty of murders, but none involving the “peculiar mutilations” that were Leng’s signature.

Smithback did a quick calculation: Leng appeared in New York in the 1870s—probably as a young man of, say, thirty. In 1935, he would have been about seventy. So why did the murders cease?

The answer was perfectly obvious: Leng had died. He hadn’t found an obituary; but then, Leng had kept such a low profile that an obituary would have been highly unlikely.

So much for Pendergast’s theory,thought Smithback.

And the more he thought about it, the more he felt sure that Pendergast couldn’t really believe such an absurd thing. No; Pendergast was throwing this out as a red herring for some devious purpose of his own. That was Pendergast through and through—artful, winding, oblique. You never knew what he was really thinking, or what his plan was. He would explain all this to O’Shaughnessy the next time he saw him; no doubt the cop would be relieved to hear Pendergast hadn’t gone off the deep end.

Smithback scanned another year’s worth of obituaries, but nothing on Leng appeared. Figures: the guy just cast no shadow at all on the historical record. It was almost creepy.

He checked his watch: quitting time. He’d been at it for ten straight hours.

But he was off to a good start. In one stroke, he’d uncovered another half-dozen unsolved murders which could likely be attributed to Leng. He had maybe two more days before his editor started demanding results. More, if he could show his work was turning up some nuggets of gold.

He eased himself out of the comfortable chair, rubbed his hands together. Now that he’d combed the public record, he was ready to take the next step: Leng’s private record.

One thing the day’s research had revealed was that Leng had been a guest researcher at the Museum. Smithback knew that, back then, all visiting scientists had to undergo an academic review in order to gain unfettered access to the collections. The review gave such details as the person’s age, education, degrees, fields of specialty, publications, marital status, and address. This might lead to other treasure troves of documents—deeds, leases, legal actions, so forth. Perhaps Leng could hide from the public eye—but the Museum’s records would be a different story.

By the time Smithback was done, he would know Leng like a brother.

The thought gave him a delicious shudder of anticipation.

FOUR

O’SHAUGHNESSY STOOD ON the steps outside the Jacob Javits Federal Building. The rain had stopped, and puddles lay here and there in the narrow streets of lower Manhattan. Pendergast had not been at the Dakota, and he was not here, at the Bureau. O’Shaughnessy felt an odd blend of emotions: impatience, curiosity, eagerness. He’d been almost disappointed that he couldn’t show his find to Pendergast right away. Pendergast would surely see the value of the discovery. Maybe it would be the clue they needed to break the case.

He ducked behind one of the building’s granite pillars to inspect the journals once again. His eye ran down the columned pages, the countless entries of faded blue ink. It had everything: names of purchasers, lists of chemicals, amounts, prices, delivery addresses, dates. Poisons were listed in red. Pendergast was going to lovethis. Of course, Leng would have made his purchases under a pseudonym, probably using a false address—but he would have had to use the samepseudonym for each purchase. Since Pendergast had already compiled a list of at least some of the rare chemicals Leng had used, it would be a simple matter to match that with the purchases in this book, and, through that, discover Leng’s pseudonym. If it was a name Leng used in other transactions, this little book was going to take them very far indeed.

O’Shaughnessy glanced at the volumes another minute, then tucked them back beneath his arm and began walking thoughtfully down Broadway, toward City Hall and the subway. The volumes covered the years 1917 through 1923, antedating the fire that burned the chemist’s shop. Clearly, they’d been the only things to survive the fire. They had been in the possession of the grandfather, and the father had had them rebound. That was why the antiques dealer hadn’t bothered to examine them: they looked modern. It had been sheer luck that he himself had—

Antiques dealer.Now that he thought about it, it seemed suspicious that some dealer just happened to walk into the store a few weeks after the old man’s death, interested in the safe. Perhaps that death hadn’t been an accident, after all. Perhaps the copycat killer had been there beforehim, looking for more information on Leng’s chemical purchases. But no—that was impossible. The copycat killings had begun as a result of the article. This had happened before. O’Shaughnessy chastised himself for not getting a description of the dealer. Well, he could always go back. Pendergast might want to come along himself.

Suddenly, he stopped. Of their own accord, his feet had taken him past the subway station to Ann Street. He began to turn back, then hesitated. He wasn’t far, he realized, from 16 Water Street, the house where Mary Greene had lived. Pendergast had already been down there with Nora, but O’Shaughnessy hadn’t seen it. Not that there was anything to see, of course. But now that he was committed to this case, he wanted to see everything, miss nothing. He thought back to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: to the pathetic bit of dress, the desperate note.

It was worth a ten-minute detour. Dinner could wait.

He continued down Ann Street, then turned onto Gold, whistling Costa Divafrom Bellini’s Norma.It was Maria Callas’s signature piece, and one of his favorite arias. He was in high spirits. Detective work, he was rediscovering, could actually be fun. And he was rediscovering something else: he had a knack for it.

The setting sun broke through the clouds, casting his own shadow before him, long and lonely down the street. To his left lay the South Street Viaduct and, beyond, the East River piers. As he walked, office and financial buildings began giving way to tenements—some sporting re-pointed brick facades, others vacant and hollow-looking.

It was growing chilly, but the last rays of the sun felt good on his face. He cut left onto John Street, heading toward the river. Ahead lay the rows of old piers. A few had been asphalted and still in use; others tilted into the water at alarming angles; and some were so decayed they were nothing more than double rows of posts, sticking out of the water. As the sun dipped out of sight, a dome of afterglow lay across the sky, deep purple grading to yellow against a rising fog. Across the East River, lights were coming on in the low brownstones of Brooklyn. He quickened his pace, seeing his breath in the air.

It was as he passed Pearl Street that O’Shaughnessy began to feel that he was being followed. He wasn’t sure why, exactly; if, subliminally, he had heard something, or if it was simply the sixth sense of a beat cop. But he kept walking, not checking his stride, not turning around. Administrative leave or no, he had his own .38 Special strapped under his arm, and he knew how to use it. Woe to the mugger who thought he looked like an easy target.

He stopped, glancing along the tiny, crooked maze of streets that led down to the waterfront. As he did so, the feeling grew stronger. O’Shaughnessy had long ago learned to trust such feelings. Like most beat cops, he had developed a highly sensitive street radar that sensed when something was wrong. As a cop, you either developed this radar fast, or you got your ass shot off and returned to you, gift-wrapped by St. Peter in a box with a nice pretty red ribbon. He’d almost forgotten he had the instinct. It had seen years of disuse, but such things died hard.

He continued walking until he reached the corner of Burling Slip. He turned the corner, stepping into the shadows, and quickly pressed himself against the wall, removing his Smith & Wesson at the same time. He waited, breathing shallowly. He could hear the faint sound of water lapping the piers, the distant sound of traffic, a barking dog. But there was nothing else.

He cast an eye around the corner. There was still enough light to see clearly. The tenements and dockside warehouses looked deserted.

He stepped out into the half-light, gun ready, waiting. If somebody was following, they’d see his gun. And they would go away.

He slowly reholstered the weapon, looked around again, then turned down Water Street. Why did he still feel he was being followed? Had his instincts rung a false alarm, after all?

As he approached the middle of the block, and Number 16, he thought he saw a dark shape disappear around the corner, thought he heard the scrape of a shoe on pavement. He sprang forward, thoughts of Mary Greene forgotten, and whipped around the corner, gun drawn once again.

Fletcher Street stretched ahead of him, dark and empty. But at the far corner a street lamp shone, and in its glow he could see a shadow quickly disappearing. It had been unmistakable.

He sprinted down the block, turned another corner. Then he stopped.

A black cat strolled across the empty street, tail held high, tip twitching with each step. He was a few blocks downwind of the Fulton Fish Market, and the stench of seafood wafted into his nostrils. A tugboat’s horn floated mournfully up from the harbor.

O’Shaughnessy laughed ruefully to himself. He was not normally predisposed to paranoia, but there was no other word for it. He had been chasing a cat. This case must be getting to him.

Hefting the journals, he continued south, toward Wall Street and the subway.

But this time, there was no doubt: footsteps, and close. A faint cough.

He turned, pulled his gun again. Now it was dark enough that the edges of the street, the old docks, the stone doorways, lay in deep shadow. Whoever was following him was both persistent and good. This was not some mugger. And the cough was bullshit. The man wantedhim to know he was being followed. The man was trying to spook him, make him nervous, goad him into making a mistake.

O’Shaughnessy turned and ran. Not because of fear, really, but because he wanted to provoke the man into following. He ran to the end of the block, turned the corner, continuing halfway down the next block. Then he stopped, silently retraced his steps, and melted into the shadow of a doorway. He thought he heard footsteps running down the block. He braced himself against the door behind him, and waited, gun drawn, ready to spring.

Silence. It stretched on for a minute, then two, then five. A cab drove slowly by, twin headlights lancing through the fog and gloom. Cautiously, O’Shaughnessy eased his way out of the doorway, looked around. All was deserted once again. He began making his way back down the sidewalk in the direction from which he’d come, moving slowly, keeping close to the buildings. Maybe the man had taken a different turn. Or given up. Or maybe, after all, it was only his imagination.

And that was when the dark figure lanced out of an adjacent doorway—when something came down over his head and tightened around his neck—when the sickly sweet chemical odor abruptly invaded his nostrils. One of O’Shaughnessy’s hands reached for the hood, while the other convulsively squeezed off a shot. And then he was falling, falling without end . . .

The sound of the shot reverberated down the empty street, echoing and reechoing off the old buildings, until it died away. And silence once more settled over the docks and the now empty streets.

FIVE

PATRICK O’SHAUGHNESSY AWOKE very slowly. His head felt as if it had been split open with an axe, his knuckles throbbed, and his tongue was swollen and metallic in his mouth. He opened his eyes, but all was darkness. Fearing he’d gone blind, he instinctively drew his arms toward his face. He realized, with a kind of leaden numbness, that they were restrained. He tugged, and something rattled.

Chains. He was shackled with chains.

He moved his legs and found they were chained as well.

Almost instantly, the numbness fled, and cold reality flooded over him. The memory of the footsteps, the cat-and-mouse in the deserted streets, the smothering hood, returned with stark, pitiless clarity. For a moment, he struggled fiercely, a terrible panic bubbling up in his chest. Then he lay back, trying to master himself. Panic’s not going to solve anything. You have to think.

Where was he?

In a cell of some sort. He’d been taken prisoner. But by whom?

Almost as soon as he asked this question, the answer came: by the copycat killer. By the Surgeon.

The fresh wave of panic that greeted this realization was cut short by a sudden shaft of light—bright, even painful after the enveloping darkness.

He looked around quickly. He was in a small, bare room of rough-hewn stone, chained to a floor of cold, damp concrete. One wall held a door of rusted metal, and the light was streaming in through a small slot in its face. The light suddenly diminished, and a voice sounded in the slot. O’Shaughnessy could see wet red lips moving.

“Please do not discompose yourself,” the voice said soothingly. “All this will be over soon. Struggle is unnecessary.”

![Книга Legendary Moonlight Sculptor [Volume 1][Chapter 1-3] автора Nam Heesung](http://itexts.net/files/books/110/oblozhka-knigi-legendary-moonlight-sculptor-volume-1chapter-1-3-145409.jpg)