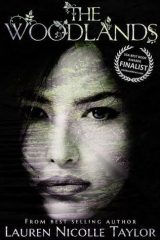

Текст книги "The Woodlands"

Автор книги: Lauren Nicolle Taylor

Жанры:

Научная фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 7 (всего у книги 20 страниц)

If I had known this was the day, I wonder if I would have done anything different. Could I have stopped the horrible events that unfolded before my eyes?

Maybe.

Probably not.

I had worked late into the night, putting coats of oil and endlessly sanding my jewelry box. I was obsessing over it, wanting to make sure every part of it was perfect. Not even admitting to myself how much it meant to me.

Now that I was back in the workshop, after a restless nights’ sleep, I stepped back and tried to appraise it critically. It was certainly eye pleasing. It didn’t look like something I made and I couldn’t help wondering where I had pulled it from. How was I able to create something so good? It was not like me, or at least not what I thought I was like. A sense of unfamiliar pride swelled inside me. I was nervous, but satisfied that this would be good enough. The dream crept back into my mind, a shiny, haze of a picture. My own workshop, my own work.

“Don’t worry, Soar, it’s fantastic!” said Henri, putting his long arm around my shoulders. I took a deep breath. He smelled wonderful, like a combination of freshly sanded timber and oil. I could tell by the dark circles under his eyes that he had been here all night, his usually flawless appearance showing some cracks, a hair out of place, a crinkle in his shirt.

Henri had been the moral compass of the group. From what I had gathered, life in Birchton was even harsher than in Pau. Henri had been raised in an extremely strict environment and his appearance reflected that. His ash-blonde hair was always neatly combed back. His uniform was always impeccable. Outwardly, he looked like the perfect student, serious and dedicated. But there was such a warmth and kindness to him. He was always looking out for us, trying, to no avail, to get the group to settle down at meal times and in class. I admired the fact that despite his hard upbringing, he had managed to keep his soul intact, unlike many of the other students. He was the one that we would look to, in case we had gone too far, and he would always let us know, but in a kind and measured way. Having someone look out for me wasn’t something I was very used to. In Pau, everyone looked after themselves. I only knew one other person who behaved like Henri, or at least used to.

“Thanks, I love yours,” I said, thinking it was not enough but not knowing what else to say. I ran my hands over his impressive desk. Henri had constructed a strong-looking desk out of the pale orange-colored timber of his hometown. It was deceptively complicated. Upon closer inspection, you could see the craftsmanship that had gone into it. The top, lockable drawer that slid open effortlessly and the carved handles made it look extraordinary. Each one was shaped like a delicate birch leaf, curled perfectly to allow the opener to grasp it and pull with ease.

As I shut the drawer, Mister Gomez stormed in looking like a terrified mole, squinting and crashing into things. I suppose, for him, this was an assessment of his teaching skills, and for us to do poorly reflected directly on him. But when he took in the superb creations his students had produced, his shoulders, tensed and almost touching his ears, seemed to relax a little. Until his dark eyes glanced at Rash’s wobbly-looking table.

“Listen up everyone. We have until twelve to finish. Rasheed, I suggest you attend to the wobbly leg on that table.” He proceeded to walk around the workshop, pointing out minor issues that needed to be fixed. When he came to me, I was just about to pick it up and take it over to the sanding bench. He put his hand on my wrist. It was all sweaty, but I did my best not to pull back.

He said, “Leave it, Rosa, I don’t think there’s any more you can do.” I think I must have looked hurt or worried because he quickly followed it up with, “You surprised me, girl, it’s excellent work,” then he gruffly snatched the box out of my hands and placed it towards the end of the judgment line.

Rash winked at me and mouthed the words, “Told ya,” and then started squirting way too much glue into the join between his tabletop and leg. I wished he had taken this more seriously. I highly doubted he would end up in the high stream with that table.

The other boys were all working really hard. They were focused and I didn’t want to distract them. I wasn’t allowed to help, so I asked Mister Gomez if I could take some free time. He waved me off, muttering something about having enough to worry about, as he snatched the hammer out of Rash’s hands. Rash had given up on glue and was trying to hammer a wedge in the join between the leg and the table to even it up. Bricklayer, I thought.

I wandered outside and made my way back to the Arboretum. The weather was getting colder and my thin cotton uniform was failing to shield me from the chill. Soon, I thought, there would be a light blanket of snow covering most of these tree branches. It would be a beautiful sight, another I had never seen before. I could imagine trees laden with heavy snow, green contrasting against the cool white. In Pau we had snow. But snow on concrete was just snow on concrete—it was nothing special.

I welcomed winter; there would be less people outside. I could walk freely around the trees without interruption. I walked from plant to plant reading the plaques. Each time, I remembered a little more, finding I could repeat the names of at least half of the plants in here just by looking at them.

I arrived at my favorite place. The Banyan tree’s limbs stretched out, beckoning for me to climb under their thick, grey branches. The hanging roots dripped down, providing a curtain under which to shelter. I pulled them apart and nestled in amongst the roots and the damp dirt. I had about one hour to wait.

I thought about what had got me here. Hate and love in equal measure. Then I thought about how I felt now. I had changed. I had let go of the hate now. The love was harder to free but maybe, in time, that too would fade. I had learned so much. Things about myself I had never known existed, what I was capable of. Somehow I had managed to make friends. Most importantly, I felt like I had a place. In this awful situation, I had found something good. I was amazed at myself and reluctantly, proud. I held one of the Banyan roots in my hand. It was dangling maybe a centimeter off the ground, stretching and straining to get to the cool, damp earth. If I had a place, maybe I could start to heal, start to grow. I let the root fall, not long now and it would find its way to the ground, be nourished and in turn nourish its mother tree.

I heard him before I saw him. One thing he never was, was quiet. Joseph stomped up the path, snapping twigs and branches as he went. I retreated further behind the curtain of grey roots and watched. He was pacing back and forth, clearly distressed. He plonked himself down against the Brasilwood, his large form looking out of place next to the tiny trunk. Sitting right in the spot where two months ago, I had read his letter. He sat with his elbows on his knees. His body was tense, like a spring trap, as he pulled his golden curls back from his face.

My heart ached for him. He was only a few meters away, but it felt like such a distance to cover. I wanted to crawl over to him and hold him, have him hold me. But remembering the letter, I froze, feeling that stone where my heart used to be, twisting and wringing out my insides.

I clutched my chest, the imagined pain starting to feel real. I couldn’t breathe. The once comforting roots of the tree now felt like they were strangling me, trying to tie me down, pull me into the ground. I knew I couldn’t sit there for much longer. But I didn’t want to burst out of the tree, revealing that I had been watching him this whole time. I struggled to contain myself but thankfully, after about five minutes, he sat up straight, like he had remembered something important. He muttered, “I have to do it,” and then he stormed off determinedly.

I parted the curtain of knobbly roots and stepped out, surveying the scene. I wished I had time to sort through these feelings, to try and understand what I had just seen. He always seemed so happy when I saw him. I wondered if it was something that had just happened—had he done poorly on his assessment? I doubted it. There was no time. There were no answers anyway. I ran back to the workshop with minutes to spare, distracted and weary.

I walked through the swinging double doors to the workshop and was confronted with a re-stressed Gomez flustering his hairy arms about. “Good, Rosa, you’re here. The judges will be here any second now.” He grabbed me by the shoulders and jostled me into line with the others, leaving palm-shaped wet patches on my t-shirt. I noticed that Rash had somehow managed to salvage his table and it stood straight. It was terribly simple and I didn’t hold much hope that he would score well, but at least it wasn’t leaning at a forty-five-degree angle anymore.

I stood between Rash and Henri, my two favorite people, and held my breath. The judges entered. One woman and one man both dressed in a red uniform with the same gold trim as the other guardians. I didn’t recognize them; they must have been from outside the Classes. Readers in hand, they walked to the first piece and circled it, whispering to each other. They scanned the boy’s wrist and proceeded to type things in, adding a score to his name. The woman seemed senior. She ordered the other one around, occasionally tucking her grey bob behind her ears as she spoke in a low, hissing whisper. She had a stern, nasty face that was set in a permanent frown. The man was younger and kept looking to her before typing in his notes. His small, brown face twisting like he had smelled something bad as he inspected every aspect of the pieces. He reminded me of a rat, twitching and sniffing, following the other one around waiting for crumbs to fall.

I was the second to last to be appraised and it was agonizing waiting for them to get to me. I leaned and swayed on my tiptoes, inadvertently peering at the male Guardian’s screen. He scowled at me and tucked it under his arm, protecting his piece of cheese. All he needed were whiskers to complete the transformation.

When they got to Rash, they didn’t take much time. The woman raised one eyebrow as she stared down at my friend. I noticed she was wearing makeup, a rare luxury. It was caked in the corner of her eyes, balled up bits of black grit that made her blink too much. Rash shifted uneasily from foot to foot under her critical gaze, smiling inappropriately at her. I had a moment of panic, thinking he might be stupid enough to wink at her. I wanted to whack him and tell him no amount of charm was going to help him today. When they moved on, I heard him sigh in relief. It was my turn.

The woman lifted the lid to my jewelry box with her little finger. It glided open gently, elegantly. She inspected every compartment with a critical eye, checking the workmanship meticulously. She closed the lid and ran her hand over the emblem on the front, tracing each individual circle of timber with her finger. I wanted to talk, explain to her the differences in the timbers, the purpose of each compartment. I bit my lip, tasting blood. She turned to her colleague and she smiled. It didn’t look right on her shrewd face. But her teeth were showing through her thin lips caked in dried-up lipstick. Mister Gomez was looking very pleased as she nodded her head approvingly in his direction. She typed in her scores and moved on to Henri. I relaxed a little. Rash and the other boys were all grinning at me. A feeling of elation was creeping through me, threatening to make me do something crazy, like jump in the air or yell out. Maybe this could work, I thought. My love of this craft was not misplaced—I might actually succeed.

The judges both seemed quite pleased with Henri’s desk as well, nodding and whispering in a painful performance that only heightened the tension in the room. We wanted it be over. When they had completed their assessments, the judges walked to Mister Gomez, their gold-embellished shoulders glinting under the fluorescence, and turned to face the class. I looked down the line—eight young men with their futures hanging in the balance. They were all strong, good boys with sawdust in their hair and oil on their calloused fingers.

“You have all performed satisfactorily in this assessment,” she stated. “Your score will be prepared and provided to you tomorrow morning. Perez.” She motioned for him to step forward and then she placed a hammer in his hand.

I wish I had been prepared for this. I’m not sure whether it would have changed anything but maybe it would have. There could have been a chance. I could have had a chance.

Perez’s face looked devilish as he moved to the first table. Without ceremony, without hesitation, he smashed it. I watched each of my friends’ devastated faces as he moved from piece to piece, destroying their work. I couldn’t believe what I was seeing. What was the point to this? I felt each blow like he was striking me. My arms held up in defense, my body vibrating with every crash of the hammer. I couldn’t stand it anymore. Three pieces into the destruction, I screamed.

“Stop!” Everyone stared at me. The boys were shaking their heads, pleading with their eyes for me not to continue. Henri whispered, “Soar, no,” but this was me—I couldn’t stop even if I wanted to. “Please,” I begged, “you can’t do this.” I was shaking. Even as the words escaped my mouth, I knew it was futile.

Perez took three steps towards me and pounded me in the face with the flat side of the hammer. I flew sideways, knocking Henri’s desk over in the process. I felt teeth from my right jaw rattling in my mouth, which filled with the metallic taste of blood and threatened to drown me. The pain was immense as it spread from my jaw up and around my head, throbbing. The torn flesh of my face was searing hot, each nerve ending screaming. I couldn’t focus, vision blurred but not from tears. I stayed silent. Trying to breathe, trying really hard not to panic.

As I lay there on the floor clutching my broken face, I wondered why Mister Gomez hadn’t warned us. He had always been strict but never cruel. This was cruelty. Then it came to me, as bits of wood and lacquer rained down on me from above. Shards of my proud creation were landing in my hair and sticking to the growing pool of blood around where I was lying. There were two reasons. One, we probably wouldn’t have tried so hard if we knew. And two, this was part of the assessment. It was a test. And I had just failed with flying colors. In one swift move, I had ruined everything.

The noise of my beautiful jewelry box being shattered marked the end for me. I knew it, as well as everyone else in the room. Rash stepped forward, foolishly trying to diffuse the situation. “C’mon guys…” he said as he took a step towards me. The expression on his face showed me how bad I must have looked. The grey-haired woman stepped forward and touched a black device lightly to his chest. His body jolted unnaturally and he fell to the floor. I hauled myself over to him, leaving a smear of blood-sticky woodchips in my wake. He was still breathing but he was unconscious. I saw the other boys, my treasured family, moving forward, like they were about to act. I pulled myself up to sitting, a mixture of blood and teeth spilling from my lips as I spoke, “No. Help Rash.” Whatever was going to happen to me, I didn’t want them dragged into it.

Two men had appeared in the doorway, dressed in the black Guardian garb. They were directed to take me by the female judge, who was definitely not whispering anymore. Her harsh shouting reverberated in my swollen head. “Remove her immediately!” she barked at them, pinching the bridge of her nose like the whole thing had inconveniently given her a headache. They roughly hooked their arms under mine and pulled me to my feet. As they lugged me out the door like a sack of potatoes, I could see the boys helping Rash to his feet. I was thankful that for now, at least, he had escaped further punishment.

The Guardians were trying to make me walk. I tried but I felt dizzy and uncoordinated, like my legs were made of jelly. My shirt was soaked with blood and my eye was starting to close up. One of the men gave up and slung me into his arms. I had no strength to struggle. Besides, there was nowhere to run to.

The hall started to narrow before my eyes. I felt my body being hollowed out and filled with lead. Everything that I had tried to build was gone, forever. Any warmth I had in me was replaced with a cold dread, knowing that I would most likely be dead in a few hours. My vision was getting tighter and tighter, until all I could see was a spot of light dancing before my one good eye. I felt my body being dumped on a hard, cold surface. I exhaled, farewelling my life. Hope was gone. Death was imminent. I prayed it would be fast.

It felt like I had missed something, like there was a gap in my memory. I didn’t know how long I had been here and what they were asking of me. I knew that it was big. Something I was resisting. Things kept slipping and I needed to retrace my steps. I felt like it was essential I figured it out soon, before something bad happened.

There was an ominous cloud hanging over my head, pushing down on me, pushing me to look deeper. I curled around the emptiness and pulled a yellow quilt around my shaking shoulders. This was home, right? It looked like home, but there were small things that didn’t quite fit—like the small crack above my bed that I used to trace with my finger when I couldn’t sleep and the quilt made from scraps of fabric, sewn by my mother, the faded spot on the curtain where the sun hit in the afternoon. There was no sun here. It felt like we were underground. It was cold. My ears sought noise from the outside world but there were none. No birds, no wolves howling, no lawn mowers grumbling. All that was familiar to me was twisted or simply missing.

And somewhere at the back of all of this, there was something pushing. A fissure was appearing in the black spots of my memory, one small shaft of light. I felt like if I could get my fingers in and pry it apart, things would become clearer. Thoughts ticked over time and I came back to home. Was I even supposed to be at home?

I was tracing that imaginary crack over and over when they came in. One, two, three people, smiling unconvincingly. “How are you feeling?” one asked, patting my arm absently. She peeled back the covers and wrapped a black bandage around my arm, inflating it until it hurt while pressing her cool fingers to my wrist. Someone handed me a tray of food and a milkshake, which they told me had the extra vitamins I needed in it. I didn’t register faces, voices. It seemed unimportant. Food, however, seemed extremely important and I eagerly dove into my meal and took sips of my shake, while nodding at their questions. A tall man, with a frightening smile, all giant teeth that didn’t quite fit in his mouth, asked me if I’d had any nausea that day. I shook my head and touched my stomach instinctively. My milkshake stuck in my throat.

I rolled my hands over my middle, expecting loose clothing and a flat stomach, my fingers pressing down. “What the hell is this?” I screamed. I was bulging. I looked like I had swallowed a sack of rice, or had been blown up with air. My once smooth, smooth stomach had been replaced by a protrusion, a lump. Concern flickered on the blonde lady’s face but it was quickly covered up, her composure a serene mask. The other, older woman, held my hand away from my stomach. She held it tightly, as if trying to stop me from touching it again. I felt her manicured nails digging into my wrist.

“Now calm down…” someone whispered as I felt my armed pulled upward violently and jabbed sharply.

A fog rose up around me. I was floating on a grey cloud, unaware and indifferent. I went back to feeling like I couldn’t quite grasp what was happening to me. But somewhere, a thought was pawing at me and I got the sense this had happened before, many times more than once.

Was I dreaming or was this real? Things swirled around in my head, blood, warmth, shredding pain. I reached out and grasped at the one thing I knew was true. My name was Rosa, I was sixteen years old, and I surrendered myself to the Classes early because my mother was pregnant. But even this memory seemed wrong. Wasn’t there a boy? I shook my head, trying to clear it, but his face remained a blur surrounded by a blondish halo. I hit my thighs with my fist weakly in frustration. It was like I was climbing the inside of a bowl, always slipping back down to the bottom every time I thought I had made some progress.