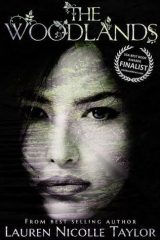

Текст книги "The Woodlands"

Автор книги: Lauren Nicolle Taylor

Жанры:

Научная фантастика

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 20 страниц)

BY LAUREN NICOLLE TAYLOR

CLEAN TEEN PUBLISHING, INC.

This is a work of fiction. The characters, incidents, and dialogues are products of the author’s imagination and are not to be construed as real. Any resemblance to actual events or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Woodlands

Copyright © 2013 by: Lauren Nicolle Taylor

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information address:

Clean Teen Publishing

PO Box 561326

The Colony, TX 75056

www.cleanteenpublishing.com

For more information about our content disclosure, please utilize the QR code above with your smart phone or visit us at www.cleanteenpublishing.com.

For my friend Chloe,

without whom The Woodlands would never have

made it out of the desk drawer.

And for my husband Michael,

you are my Joseph.

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

BEFORE

When I was eight years old, I got the distinct and unsettling impression I was unsuited to life in Pau Brazil. That my life would go off like the single firework on Signing Day. A brilliant burst of shimmering color and noise that exploded in the sky momentarily, then disappeared into the black night air.

A slip of yellow paper shot under the door in the evening, spinning across the floor like a flat top and colliding with my father’s foot. It was an official notice informing everyone that Superior Grant was visiting in three days’ time. He had a special announcement to make.

Citizens scrambled to make their lawns more perfect than they were before. Uniforms were pressed and cleaned. All the children were expected to line up around the edges of the center Ring and await the great man himself.

I was excited, but my excitement had an edge of terror to it—this was a Superior. My father warned me to not get my hopes up.

“He’s just a man, like the rest of us,” my father said as he knelt down to adjust my oversized uniform and tighten my ribbon.

My mother tsked and fussed around in the kitchen. “Pelo, don’t say things like that to her. I don’t want you filling her head with your ridiculous ideas.”

His eyes darted to her for a second but then he locked on me. “Ideas are never ridiculous. Ideas are just that, ideas. Putting them into practice… now that’s when things get ridiculous,” he smirked.

I drew my eyebrows together, confused. He patted my head and took my hand. “C’mon, let’s get this farcical procession over with.”

“Pelo!” My mother’s angry foot stomp clacked on the tiles.

He put his hands up in the air in surrender. “All right, all right. I’ll behave,” he said, and then he winked at me. I beamed up at him. He was a shiny hurricane and I was happy to be swept away.

They were going to choose a child to come forward and ask Grant a question. Our nervous teachers had given each student a card with an innocuous question on it. I looked down at the printed piece of yellow cardboard. Mine said, ‘Superior Grant, how does it feel to be the descendant of the brilliant founder of the Woodlands?’ I frowned. I knew that Grant was descended from President Grant of the United States of Something or Other. We learned that at school. We were also taught that Grant was the initiator of the treaty; he orchestrated the signing in the last days of the Race War and negotiated peace. But this question was boring and I was sure no one would care about the answer. I would much rather have asked him what kind of food Superiors got to eat. Were they stuck with the hundred-year-old canned foods we were? The globs of vegetable that came out in one solid, gelatinous lump, identifiable only by their difference in color, as most of the labels had peeled off years ago. Green could be, but was not reserved exclusively, for peas. Orange for carrots, or maybe pumpkin. It goes on—an exciting Woodlands guessing game for ages four and up.

In my mind the Superiors must have been super-people. Beautiful, tall, and powerful.

I could barely contain my disappointment when Superior Grant stepped out of the helicopter. He was regular sized and a little overweight. He was handsome, but not like my father. It was the kind of handsomeness that required maintenance. Grey, slicked-back hair, manicured beard. He had the black military uniform on. Gold tassels swung festively in the wind created by the slowing chopper blades.

Despite this, I still wanted him to pick me. I leaned into the circle, standing on my tiptoes. My parents were a few rows behind me, heads bowed solemnly.

I kept my eyes down when Grant came close, trying my hardest not to bounce up and down like some of the other kids who were reeling with nervous energy. When the boots stopped in front of me, I stopped breathing, still staring at my feet.

A policeman tapped me on the shoulder sharply with a baton and said, “You. Ask your question.” I couldn’t believe it. And very suddenly didn’t want to.

I rubbed my shoulder and looked up into Superior Grant’s face, taking in his tight forehead and even tighter jaw. I tipped my head to the side, wondering what made him so special. When I realized I shouldn’t be staring, I cast my eyes towards my shaking cardboard question, barely able to see the typed words that seemed to want to jump off the page. I opened my mouth to speak but the way he was eyeing me made me freeze, the question sitting on my lips like an un-blown bubble. It was like I had suddenly grown extra limbs or had spots all over my face because his nose scrunched up and his eyes watered like he thought I was diseased.

He took a step closer and peered into my face. I leaned away, the musty, vinegary smell of his breath overpowering. “What’s wrong with her eyes?” he said in a strange drawn out twang, like ‘whaat’s wrawng with her eyeees?’

I felt anger rising inside me like an over-boiling pot. I glared at him. My father had taught me that my eyes were nothing to be ashamed of. It was uncommon but it didn’t mean there was anything wrong with me. I had one blue eye and one brown. So did my father. Grant raised an eyebrow, unperturbed by my narrowed eyes and reddening face. He placed his hand on my eyelid and lifted it, straining my eye socket. Then he moved to the other eye and did the same. I shook my head free of him and before I knew what I was doing, I smacked his hand away.

I heard a couple of people in the crowd laugh but the rest seemed to have simultaneously stopped breathing. Behind me someone was moving through. Grant smiled down at me cruelly.

“Poor decision, child,” he said smoothly. Then he turned and walked away.

I barely had time to process my mistake when a policeman grabbed me by the scruff of my neck and pulled me upwards to face the crowd. He rattled me around like a bag of apples and I could feel my inside bruising.

“See here. Here is lesson for all of you of how NOT to behave in the presence of Superior Grant.”

I saw my father’s wobbling figure moving towards me like a mirage.

As my brain started to whip into a milkshake in my skull, it occurred to me that I shouldn’t have done what I’d just done. It also occurred to me in a dangerous revelation, that I wasn’t sorry at all.

Somehow my father managed to negotiate my release. Besides, the Guardian seemed anxious to catch up to Grant, who was moving on to the next group of children. He dragged me through the crowd and we crouched behind the stone wall of Ring One, listening to the faint, quivering voice of a child asking her question. “How do you weigh your wisdom against your strength, Superior Grant?” I had the odd thought—how could wisdom weigh anything?

My father clasped his strong dark hands around my face worriedly, turning it from side to side. “Are you all right?”

I nodded, fierce tears running down my face. “I think so. I didn’t like him very much.”

He shook his head, but amusement twisted his face, “You want to know a secret?” I nodded and he leaned down to my ear. “I don’t like him very much either,” he whispered.

The crackling and whining that always preceded an announcement on the PA system started and the Superior Grant’s elegant voice carried out over the sea of people.

“I am here to announce the Superiors have decided large families pose a direct threat to the security of the Woodlands. Brothers, sisters, and the bonds that result create an US versus THEM culture, which is unacceptable and in direct opposition with All Kind.” He sounded bored as he talked. “Hence, we will allow each couple to house only one child at a time. This is not negotiable and any violations will be strictly dealt with.”

The crowd murmured but that was the extent of their opposition.

Then he said, “Have your elder children available for collection by tomorrow morning.”

The crowd hummed and then an angry voice splashed out and fell flat on the stones. “You can’t take our children!” Other voices began to rustle like the crackle of shifting leaves.

I took a step up onto the ledge of the wall to get a better look. I watched as a policeman moved slowly but deliberately towards the man that shouted, with a face like horror. He took his baton and clapped the side of the man’s head, hard, to show they could do whatever they wanted. As it cracked, an arc of blood sprayed onto the faces of people closest, like droplets of red rain. The crowd fell back from the man’s crumpled body in a wave. A woman screamed and threw herself down beside him. The policeman joined the others, twirling his baton around in his hand and wiping the blood off on his pants. Everything went quiet, like the guardian had swished all the air out of the circle. If there were birds, even they would have ceased to breathe.

I looked to my father for his reaction. His face was white, his whole body shaking with anger, his mouth open slightly like he wanted to speak. Don’t speak, I prayed.

He crouched down and shouted through the gaps between people’s legs, “President Grant is an insane dictator!” then stood up quietly and did a brilliant impression of a normal, frightened person. The policeman’s head snapped around and searched the crowd but no one was willing to point him out; they didn’t want to be punished.

He pulled me to him tightly and I clung on to his leg.

“Are they going to take me away?” I asked naively.

“No beautiful girl,” he whispered. “You are all we have.”

When we got home my parents fought like never before. I stayed in my room with my ear pressed to the wall. I couldn’t hear my mother at all but I caught my father’s response to everything she said.

“No.”

“Come on, it wasn’t that bad. She got away, didn’t she?”

“Yes, but she’s a child. She’ll learn to control herself.”

“Yes, exactly like me. I’m still here aren’t I? You’re being absurd. She needs her father.”

“You wouldn’t do that.”

Silence.

The next morning at school, my class was half-empty and half-full of red-eyed, stain-cheeked children who had lost their brothers and sisters.

In my child brain, where an hour could seem like a week and a gap of months seemed to go by in an instant, it was like my father was swapped with Paulo almost immediately. Suddenly, my mother was remarried, my father had disappeared, and where there was once warmth and laughter, there was only hardness. Looking back, I’m sure that’s not quite how it happened but like I said, I was eight.

Now, at sixteen, I was amazed I had lasted as long as I had. And after the twentieth time of my mother asking me why I was like this—I started to wonder myself.

I think the answer was a combination of things. The first being that I severely lacked that healthy dose of fear most people seemed to have. Fear being healthy, because not fearing the Superiors was about as good for you as a mugful full of bleach with your morning toast. The other reason, which took me longer to work out, was that even though I hated my father for leaving, I still wanted to hold on to him somehow. His memory was slippery and I struggled to get my hands around it. But when I did something unexpected, something to raise the eyebrows and sometimes the hands of my teachers, my father’s face became clearer in my mind, the edges sharpened. I could see him smiling at me crookedly and pretending to be cross even though I knew he wasn’t. These memories would pull in and out of focus like flipping photos.

And ultimately, when almost everything I did was controlled by the Superiors, by my teachers and by Paulo, I took what little control I could for myself and held onto to it fiercely.

It was a slow dust of a day. The earth swirled in mini tornados, scratching up the eight meter walls and slipping back down again, because in this place there was nothing for it to cling to. It skittered across the grass, kissing the blades, and tearing around the perfectly manicured trees that sat in the front yard of every home. Here in the rings of Pau Brazil, nothing settled—nothing ever could.

I shrugged on my grey uniform. My mother was right about it being cheap and nasty. It was itchy and it seemed to beckon hot air and repel cool air. It clung to the wrong parts of me and billowed unflatteringly everywhere else. I didn’t really care. Everyone looked the same so it didn’t matter. I let the back of the shirt fall, wincing a little as the rough cloth brushed against my sliced-up skin. I couldn’t quite see it but I could feel it lightly with my fingertips, raised ribbons of split flesh. New scabs were already forming over the old scars. I never gave it a chance to heal. Soon there would be fresh cuts to add to the healing ones. I gathered up my assignment papers and shoved them in my bag, placing my mother’s treasured mascara into my pencil case. She would kill me if she knew I had it. It was given as payment about ten years ago and she only used it sparingly and on very special occasions. Well, this was a special occasion, I thought as I smiled to myself. My lips fell quickly as I remembered today was Friday. Friday was the worst day.

I tried to get out before she saw me, edging along the faded carpet, the door just in my sights, but a hand grabbed the back of my shirt and gently halted my stride. I thought maybe she knew, but her face only showed the same exhausted apathy it always did.

“Rosa, please eat something before you go.” My mother sighed, her hand falling to her side. She looked tired, ill, a hazy shade of green sitting just beneath a layer of dark brown skin like she was being diluted. I rolled my eyes at her.

“You don’t need to whisper, Mother. I’m sure Paulo approves of you feeding me. It’s the rules, remember?”

She nodded, her hand trembling a little as she put the kettle on and started the ridiculously particular process of making tea for her husband so it was just right.

I listened for sounds of Paulo and heard the shower running. I nodded and picked up some toast. As I was spreading a very thin layer of jam on the bread with my mother eyeing my every move, I saw the billow of steam push out into the hall. He was out, and so was I. I slammed two pieces together and made a toast sandwich. Half walking/half running out the door, I yelled out, “Have fun sorting apples, Paulo. I hope you don’t end up in the off bin with the rest of the rotten ones!”

I turned around and saw my stepfather’s expression as the door rebounded open from me slamming it too hard. His dark face was a wrinkled mask of pure wrath. Good.

Satisfied, I walked to school following the curve of Ring Two until I reached the first gate. It was chilly and I cursed myself for not bringing a jacket. I sought out a sunny patch on the wall and stood with my back against it, stalling. The wall was warm where the sun touched it, yet it always gave me shivers. At least eight meters tall above ground and four meters under, I felt that trapped rat feeling and kept moving. I know not everyone felt this way but I couldn’t help it. We were trapped, even if they said it was for our own protection.

I scanned my wrist tattoo at the Ring gate. It opened reluctantly, groaning like it had just woken up. I passed through it, my eyes holding contact with the camera that was following my movements. Quietly laughing, I stepped backwards, then forwards, the small black eye zipping as it tried to follow my sporadic movements. When I was done teasing, it closed behind me only to be forced to creak open for someone else a second later. I wasn’t the only one who was running late. The difference being, when the gate opened, the other kids ran through it and sprinted to the school like their life depended on it. I took my time. Being tardy would result in a detention. I needed a detention.

I peered through the iron bars to see the older kids hanging around outside one of the classrooms, their backs against the grey-green rendered walls. This would have to be their last day. The five students exuded the stagnant combination of nervousness and hope—prisoners about to receive parole. I snorted to myself. There was no hope, just change. They were going off to the Classes in a few weeks’ time.

I arrived at the school gate and scanned my wrist again. The double gates opened and I fell in to line with the stragglers. The neat rows of concrete classrooms looked dull and uninviting like the rest of the town. As I passed the older kids I heard a boy say, “Yeah, I’m hoping for Teaching or maybe Carpentry.” His voice sounded confident, but with an edge of resignation tacked on, making his voice sound strong at the start only to peter out by the time he got to the end of his sentence.

The girl standing next to him bumped his shoulder affectionately, her red-brown ponytail swinging and brushing his arm lightly. He flinched and pulled away like it bit him. “Maybe we’ll get in together. Wouldn’t it be great to be allocated the same Class?”

The boy shrugged. “Doesn’t much matter, we’ll be separated anyway, you know that.”

Smart, I thought, the girl needed to be shot down now. There was no future for anyone from the same town. The great claw of the Superiors would make sure of that. I imagined it like a sorting machine, kind of like what Paulo did, but instead of apples, the Superiors sorted races and Classes. These kids were going to be plucked from Pau Brazil, thrown into the Classes, and separated out into Uppers, Middles, and Lowers. The boy was right, at the end of training at the Classes, they would certainly be separated. Kids from the same town were not allowed to marry.

As I rounded the corner and made my way into my first lesson, I snatched a glimpse of the hopeful girl’s face. It offended me. Her eyes were wide and brimming with moisture. I had little sympathy. This was the way things were. She needed to accept it. And really, she was lucky. I envied her. At least she was getting out of here soon.

First class. The teacher stood in front of us and asked us the same five questions she asked us every day. Pacing back and forth in her sensible shoes and friction-causing nylon stockings, she nodded as the class answered in unison. I scrunched up my nose; a woman that large shouldn’t pipe herself into stockings that tight. The way her thighs were rubbing together, I thought she might spontaneously combust.

A while ago, I started formulating my own answers in my head. Different every time to beat the monotony. Today I went with a root vegetable theme.

“Who are we?” she barked in a low, almost manly voice.

“Citizens of the Woodlands,” a chorus of bored teenagers replied.

I mouthed the words, ‘Various vegetative states of potatoes’.

“What do we see?”

“All kind,” we sung out loudly. The meaning lost on some but other eyes burned fiercely with belief. As a potato, I thought, and having no eyes. I am not qualified to answer that question.

“What don’t we see?”

“Own kind,” we said finitely.

I muttered under my breath, “Everything, geez, I’m a potato.” I laughed to myself just at the wrong time, when the whole class was silent. The teacher gave me a sharp look, her black, olive-pit eyes narrowed.

“Our parents are?” she snapped, whipping her head to the front.

“Caretakers.”

“Our allegiance is to?”

“The Superiors. We defer to their judgment. Our war was our fault. The Superiors will correct our faults.” Our faults being that we had not yet developed into the super race that was to prevent all future wars.

I looked around the classroom. Most were dark skinned or tanned, dark hair and dark eyes. One girl had conspicuously fair hair compared to her caramel skin; she was favored in the class since she looked like the ideal Woodland citizen. Her parents must have ‘mixed appropriately’. Kids like me were too dark, too short, and my eyes were undesirable to say the least. I shrugged; I would have had better luck currying favor if I really was a potato.

I peered down at my skinny, dark fingers, the cracks in my palms darker than the skin surrounding them. Two hundred and fifty years on, despite the purposeful splitting up of families and distribution of races amongst the towns, you could still tell where a person came from. You could tell that my mother was Indian, as you could tell that I was half Indian, half Hispanic. The whole, All Kind and Own Kind thing hadn’t worked the way they wanted it to. People didn’t choose their mates because of their race but they didn’t not choose someone because of their race either. I guess you can’t just mix everyone up and assume they’ll make the choice you want them to.

My father used to say, ‘You can’t help who you fall for,’ but then he also said he thought the Superiors were about to change everything and start forcing us to mate with someone of their choosing. That was eight years ago and nothing had happened yet. I massaged my temples, feeling a slicing headache coming on. I hated him popping up in my mind without prompting and besides, my father was wrong about a lot of things.

The teacher smacked the table with the flat of her palm. “Good. Let’s begin.”

The first few classes went by as they always did. No one sat next to me, not that I cared. I was used to being treated like I radiated some awful smell. Sometimes I used to sniff my armpits and then look around the class. It got a couple of laughs, but didn’t endear me enough for anyone to sit next to me. I got into trouble, a lot. And it wasn’t because I was being treated unfairly or the teacher had a grudge. Trouble just found me. If there was a bad choice, I just had to make it, regardless of what would happen. I couldn’t stop myself.

I felt preoccupied, barely able to pretend I was listening to my teachers. I sat up straight, holding onto the edge of my old wooden desk like I was riding a wave, nervous excitement about my final class blowing imaginary wind through my hair.

Lunch, bell.

As the bell shrilled out across the pathetic yard, I watched a child get dragged by her hair across the plastic lawn. Her little legs struggling to find a foothold so she could stand but just sliding uselessly across the dampness. My stale sandwich stuck in my throat. Tears were streaming down the poor girl’s face. She couldn’t have been more than nine. One of the policemen wrenched her head violently, trying to pull her to standing. Blood appeared at the nape of her neck as the hair pulled out of her skin. I saw her face contort and her small pink mouth form an O as she tried not to scream.

“I think she’s had enough, don’t you? You’ll pull her hair right out of her head,” I shouted. I had the students’ attention but it was morbid curiosity—no one would help me. In fact, I saw a couple of kids take a few steps back. Both policemen turned their heads my way. One of them sneered at me, his olive skin scrunched around a bulbous nose that twisted at me in disgust. He closed the gap between us in a few long strides. His eyes had that familiar hardness to them that most of the policeman had. His were a stiff set blue, with flecks in them like chipped paint.

He laughed as he spoke, looking me up and down. “Are you talking to me, girl?” Meeting my eyes, he seemed confused as to which one to look at.

Don’t say it, I thought. If only that voice in my head was louder. “I don’t see anyone else trying to scalp a child, do you?”

His expression showed that was exactly what he had been hoping I would say. He retracted his elbow like he was loading an arrow to a bow and gave me a sharp punch to the stomach, hard enough to hurt but not hard enough to cause any permanent damage. Trained well. Part of my sandwich flew out of my mouth and I doubled over, winded. Feeling the pain spread like a stain soaking into cloth.

The policeman didn’t look back, but I could see his head swinging around, taking in the witnesses as he stormed back to his partner. Satisfied that no one of importance was watching, they continued dragging the young girl. Finally, she fainted from the pain and he scooped her up. Thankfully. Most likely her parents had done something. Probably something minor. The Superiors loved to make an example. I crossed my fingers I wasn’t going to be summoned to the center circle to watch another horrific punishment this week.

I drummed my fingers on the table in Mathematics, rubbing my sore stomach and seeing whether I could do both at once without messing it up by drumming my stomach and rubbing the desk. When I stuffed it up and started rubbing my hands across the small, wooden table, I took a pencil out and started tapping a rhythm instead. The kids around me leaned away, afraid to be sharing the same air as me. I looked up and teacher number five, whose name I couldn’t remember, was staring down at me. She snatched the pencil from my hands.

“Rosa!” she said, like it was a swear word. “Go stand at the back of the class with your face to the wall. I’ve had enough of your distracting behavior.”

I smiled at her sweetly. “Yes, Miss…um...” The teacher stared at me incredulously. Her thin tweezed eyebrows arched, her face creased in frustration. Damn, what was her name?

She put her hands on my shoulders and squeezed, digging her fingernails into my skin. “Mrs. Nwoso,” she said angrily. Blinking once slowly, I considered it.

“Oh yeah, Miss Knowitall,” I said, feeling her fingernails trying to touch each other through my flesh, burrowing a painful hole. She released me quite suddenly, shaking her head and showing her white teeth, which looked especially bright against her ebony skin.

“That’s not going to work on me today, Rosa. Stand facing the wall,” she pointed.

I shrugged and did what I was told, the eyes of my fellow classmates following me as I trudged between the neat rows of desks. I walked to the wall and leaned my forehead against a laminated poster about pi. Staring at it until my vision blurred and all I could see was the red of the circle, the numbers fading away with the monotonous tone of the teacher. The rings of Pau started to push to the front of my mind. I knew the rings were supposed to resemble a tree trunk but to me, the eight rings had always reminded me of the ripples in a puddle. And I was a stone, always trying to disrupt the order. Sending my own set of circles radiating out that didn’t match and didn’t line up with the ordered concrete.

I turned my cheek to the wall and stared out the window, watching the wind pick up leaves and bits of rubbish, hypnotizing myself and forgetting about my pain for a while. Sometimes I felt like the dust. Relentlessly banging my head against the walls, never getting anywhere. Always ending up in a pile somewhere, never in a corner though. There are no corners in a round world. Sleeting across the path, searching, settling for a second then pushed along, again and again.

I was startled out my reverie when the door started opening and closing, sending vibrations through my jaw. I quickly grabbed my things and ran out. Miss Knowitall was yelling after me, but I pretended I didn’t hear her.

Last class, History.

I hung my bag outside and retrieved the mascara, shoving it in my pocket. I pulled out my scrunched-up assignment and smoothed it out on my legs until it at least resembled a rectangle. I grinned and strode inside, ignoring the cramping in my stomach.

Everyone sat down and Mr. Singh read the roll.

“Last week, I asked each of you to write about an incident from Woodland history or select your favorite Superior and detail how the incident or person had inspired or influenced your life. I ask that you read your assignment to the class and hand in the written part for me to mark later. Who would like to go first?”

No hands went up, so he picked someone. I rolled the mascara between my palms, rolling my eyes at the student’s extremely boring presentation, clearly plagiarized from the textbook.

“…So the Superiors developed the Classes—a brilliant way to train the youth of the Woodlands, give them a purpose and a sense of fulfillment…” Ugh! Blah, blah, blah. It was a brilliant way to force children to work in jobs they would probably hate and blame it on a test. It was a brilliant way to take children away from their families, brainwash them, and fill them with Superior-loving rubbish. My brain shut me down before I yelled something out in class. Besides, thinking this way was pointless. I would have to go to the Classes too when I turned eighteen. I had no say in the matter.

“Excellent work, Miguel. Next please.”

I had to sit through a few more rambling presentations, each more sleep-inducing than the last, before Mr. Singh called out my name.

“Rosa Bianca?” he said with a note of anticipatory fear in his voice.

I took a deep breath and walked to the front of the class.