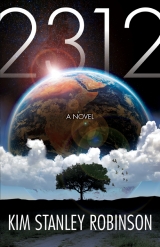

Текст книги "2312"

Автор книги: Kim Stanley Robinson

Соавторы: Kim Stanley Robinson

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 28 (всего у книги 36 страниц)

SWAN IN THE CHATEAU GARDEN

Swan flew south and took the Quito elevator up again, and again sat in on the performance of Satyagraha, singing along with the rest of the audience, dancing as an extra when everyone else did, trailing banners at the end of the first act. All the chaos of the repetitive voices crisscrossing in the middle act felt exactly right to her now, true to life. She could punch out those chants like shouting at an enemy. The struggle for peace was more struggle than peace, but now she was energized and into the flow of it.

Up in Bolivar she hurried to catch a ferry going out to meet the Chateau Garden, a big terrarium that she herself had designed when she was young—fool that she had been. This one was a Loire or Thames chateaux landscape, the big boxy stone mansions tastefully scattered about among fields of barley, hops, vineyards, and formal gardens.

It was as green as ever, she found, and looked like one of those horrid virtual game landscapes in which nothing has quite enough texture. Almost every plant in the formal gardens surrounding the great houses was a work of topiary, and not only was this a questionable idea in itself, but these had been left to go wild: the artist had gone out ice-skating on one of the ponds and fallen through the ice and drowned. Now all the whales and otters and tapirs looked as if they were being lifted up by their hair.

In the town itself (slate roofs, wood beams crossing plaster walls in standard pseudotudor) there was a large park, with a big smooth lawn, actually another of the topiarist’s masterpieces: the grass of this lawn was not simply grass, but also very fine alpine meadow grasses, sedges, and mosses, in a dense mix that also included a number of tiny low alpine ground cover flowers, including bilberry, moss campion, aster, and saxifrage, all together creating a millefleur effect that made it like walking over a living Persian carpet. Within this colorful carpet were long strips of pure fine grass, as on putting greens, all running lengthwise to the cylinder. A lawn bowling field, in fact, with about a dozen rinks.

It was winter here, as if they were in Patagonia or New Zealand, and the light from the sunspot on the sunline smeared so that shadows blurred at the edges, and the air looked rusty. Small clouds had bunched around the sunspot, white puffballs glazed pink. The shadows of these clouds dappled the town and its park, and the rolling barley fields and vineyards spread out overhead. Terrarium vertigo washed through Swan for a second as she looked up at them.

There was no Mercury House here, so she took an empty ramada on the edge of the park, under a line of sycamore trees, gorgeous in their stark winter tones. Feeling too full to sit or lie down, she put her travel bag on the square bed and went out for a walk. She stopped for tea in the village, and sitting in the café saw that a group of people were going out to the bowling green. She tossed down the last of the tea and went out to watch.

Each strip of putting grass was called a rink, and they were set lengthwise in the cylinder so that the rink would lay flat. That was important, as the Coriolis force was strong enough to push every shot to the right. The balls were asymmetrical as well, as was traditional in the sport; they were squashed spheres, like Saturn or Iapetus, and when thrown they would roll on their biggest circumference like a fat wheel, as long as they were going fast enough, but then might flop onto their side at the end, thus accentuating the fernlike curvature of the roll. It required a neat touch to put a bowl where you wanted it.

A young person approached and asked if she wanted to play a game on one of the empty rinks.

“Yes, thanks.”

The youth picked up a bag of bowls and led her to the farthest empty rink, near the edge of the field. The youth dumped the balls on the exquisite grass and Swan took one of them up. She hefted it along its long diameter; it weighed about a kilo, just as she recalled. It had been a while since she had last played. She went to the mat on which throwers had to stay, and tried to make a simple toss down the middle, on the slow side, hoping the bowl would end up in front of the jack and serve as a blocker to her opponent’s bowls.

It ran down the rink, curving only a bit, then flopped to a halt about where she wanted it. The youth chose a bowl, went to the mat, took a couple of steps forward, then crouched for a final step and the laying of the ball on the sward. Very graceful, and the ball rolled smoothly down the course, running a line that looked to be well to the left of the jack, even headed out of the rink and into the ditch, as out of bounds was called. But then the Coriolis force got its push into it and the ball curved right ever more sharply, tracing a kind of Fibonacci infalling, until it tucked in just behind the jack.

Swan would now have to try to get around her own blocker, or knock it back into the jack, so that hopefully the jack would bounce away. Four bowls per end, and with three to go they were already looking at a crowded space around the jack. Swan considered it for a while, then decided to try to use the bias of the bowl to roll one back against the C-force and see if she could get around her blocker and tap the jack. It would require a very fine touch, and the moment she made the shot she could see that she had put too much on it. “Ah damn,” she said, and was vexed enough to add, “I’m not making any excuses or anything, but I have an excuse for that.”

“Of course. Have you seen that shirt with all the excuses printed on it?”

“They made that shirt by listening to me and writing things down.”

“Ha-ha. Which one this time?”

“Well, I’ve just spent almost a year on Earth. I’m throwing everything long.”

“I bet. What were you doing there?”

“Working on animal stuff.”

“The invasion, you mean?”

“The rewilding.”

“Huh. What was that like?”

“It was interesting.” She didn’t want to talk about it right now, and she suspected the youth knew that and only wanted to distract her. “Your shot.”

“Yes.” The youth’s waist-to-hips ratio was sort of girlish, the shoulder-to-waist-to-ground lengths sort of boyish. Possibly a gynandromorph. The youth’s shot ran almost true and flopped right beside the jack. This end was looking bad for Swan. Her only recourse now was to try to knock her own blocker into the jack and hope the jack went into the ditch, which would make for a dead end. It could be done if she could throw fast and straight on the right heading. She put her little finger on the big circle of the bias, and concentrated on keeping an upright form with a straight follow-through. She rolled, and again on release knew she had missed. “Damn.”

The youth was again amused. “You have to have every finger on it when you let go.”

“Some people do,” she said.

The youth shrugged in reply. Quite young; perhaps thirty years old; a spacer.

“Is this your home?” Swan asked.

“No.”

“Where are you going?”

“Nowhere.”

The youth made a shot, which was a nicely placed blocker that meant it would be harder than ever for Swan to hit the jack with her final roll. The only chance was that same backhand.

She made her last shot and was pleased to see it roll down, take a late turn in, and bang the jack right out of the rink.

“Dead end,” the youth said calmly. Swan nodded.

They played several more ends, and the youth never made a shot that was anything less than superb. Swan lost every time.

“You’re some kind of ringer,” Swan said, feeling irritated.

“But we’re not betting.”

“Lucky for me.” She managed again to knock out the jack.

On they played. Neither seemed in any hurry to do anything else; space voyages could be like that. It felt to Swan like shuffleboard on an Atlantic ocean liner. They were rich in time—they had time to kill. The youth made several shots that were simply perfect. Swan kept throwing long, and losing. It occurred to her that this must be how Virginia Woolf had felt when she played with her husband Leonard, an expert lawn bowler from his years administering Ceylon. Virginia too had lost almost every time. The youth seemed not to care one way or the other. Leonard had probably been much the same. Well, but quite a few people played sports mostly against themselves, their opponents no more than random shifters of the problems they faced in their own performance. Still, this young person began to bother her. The neat picking up of the mat. The final flick of the fingertips at the end of a throw. The exquisite final fern tips of the Coriolised curves.

Only much later that night, as she was lying in her ramada, did it occur to Swan that the pebbles thrown at Terminator had been like a kind of lawn bowling. The thought made her sit up in bed. Set up a mat, launch a bowl—that jack would be covered.

Quantum Walk (2)

easy to note the moment Venus g is exceeded 1.0 g feels like a pull from below an entanglement with Earth rising up toward you even though you know you are descending

summer is drunken conifer grove hot in the sun new-mown hay marsh at low tide lilacs peaches barnyards

wheeled car humming down a road windows open 32 kilometers an hour plowed earth behind box hedges wind from the southwest gaudeo I rejoice a human driving don’t talk too much

carrying capacity K is equal to births minus deaths over a density-dependent impact on the growth rate added to a density-dependent impact on the death rate the unused portion of the carrying capacity if there is one will be green the overshoot portion of the carrying capacity will be black as in buildings excrement stay outdoors they have overshot

the cycloid temperament an undertow of sadness a febrile temperament be aware the human beside you is not to be comprehended

six different kinds of bird in sight at once a seated hummingbird, watching the scene, grooming itself a red-headed finch summer on earth blue sky filled with high white clouds moving east fast the hummingbird zips ahead and lands looks around beak like a needle crows and seagulls wheel competing mafias the speed of hummingbird wings muscles doing that evolution of one kind of success Canada geese the creak of their feathers as they beat their wings hummingbird song is creaky in a different way chivvying not a song a squirrel chitters much the same blue-backed hummingbird hovering there in the trees the underside of a flicker is salmon-colored

New Jersey North America August 23 2312 on the hunt on the run human now driving over hills around a marsh hills covered by low buildings moldering under knots of alder twenty kilometers an hour faces everywhere 383 people in view number shifting up and down by fifty or so as the car rolls slowly by streets of tarred gravel black

a robin with a yellow beak and raw-sienna chest black tail feathers and head white eye ring black eye neat drinking the water from a sundial gaudeo

past a garden corn pumpkins sunflowers and mullein with similar yellow flowers differently clustered I’m mulling it over

What’s that?

Nothing sorry

Oh no problem. This is nice eh?

Gaudeo

yellow flowers against dusty green in a disk filled by a spiraling pattern woven together or a tall khaki cone with crossing spirals of yellow sensory perceptions are already abstractions humans see what they expect to see they leap before they have time to look

true cognition is to solve a problem under novel conditions that humans can do this is a set of novel conditions ever since you left the building ever since you started thinking remember me there will be helpers you are defective catch and release

their brain is always making up a story to explain what is going on thus they miss things anomalies get left out but is that true? don’t they see that yellow? don’t they see the two kinds of spiral?

unlimited resources do not occur in nature competition is when both species have a net negative effect on each other mutualism is when they both have a net positive effect on each other predation or parasitism is when one gets a positive effect the other a negative effect but it isn’t always so simple intraguild predation is when two species predate each other at different moments of growth

the dark bulk of an apartment tenement shebeen the sunset sky behind and over it Magritte Maxfield Parrish get out of the car be alert make a joke don’t make eye contact

these helpers too must have plans could be using you for or against someone else this is the likeliest explanation what then how turn the tables parry riposte catch and release

Would you like to play chess? one of them says at a door

Sure, come on in guns pointed at them pointed at you

INSPECTOR GENETTE AND SWAN

Once irritated by a problem, Jean Genette never really gave up on it. Even problems officially solved sometimes still had a haunting quality, because of things that didn’t quite fit, didn’t seem right—and if a solution never was found, the problem became part of the insomniac rosary, one bead in a Moebius bracelet of beads wearily fingered in the brain’s sleepless hours. Genette was still working on the problem of Ernesta Travers, for instance, which thirty years before had troubled them all with the fundamental question of whytheir friend Ernesta had engineered a disappearance from Mars, as well as how; it was a case Jean could pursue in exile, and from time to time did, but Travers was still as absent as if she had never existed. Same with the puzzle of the prison terrarium Nelson Mandela, a locked-room mystery if ever there was one, as the asteroid seemed to have afforded no ingress or egress for whoever had brought in the fatal gun. Mysteries like that abounded in the system; it was part of the affect realm of the balkanization, many felt, but balkanization per se was not enough to explain some of these mysteries, and the inspector remained puzzled and more—transfixed, existentially confused, frustrated—by their aura of impossibility. Sometimes the inspector would walk for hour after hour, trying to make the explanation appear.

The problem of the pebble attack was not like that. It was still a new case by Genette’s standard, and it had no aura of impossibility. Almost anyone in space could have done it, and many down under atmospheres could have paid for it, or gone into space and done it, then dropped back into their atmospheres. It was a needle-in-haystack problem, and balkanization made that problem worse by multiplying the haystacks. But this was Interplan’s territory, in the end, and so on sifting the haystacks they went, eliminating what they could and moving on. It seemed pretty clear to Genette that on this one they would be looking in the unaffiliateds eventually, prying open closed worlds and poking around for the maker of the launch mechanism and the operators of the spaceship now crushed deep within Saturn. By no means were all their avenues of inquiry exhausted; there were at least two hundred unaffiliateds with robust industrial capacities; so it was more like they had barely begun.

Swan Er Hong rejoined Genette inside the aquarium South Pacific 101, a water world that filled its interior cylinder with water to a depth of ten meters, spinning against the interior of a big chunk of ice that had been melted and refrozen in such a way as to leave it transparent, so that from space the whole thing looked like a clear chunk of hail. Genette had sailed the Hellas Sea as a child, and learned to love the wild slop of a windy day in Martian g, and even all these years later had not lost the little thrill that came with feeling the fluctuating wind in one’s fingertips on tiller and line—the feeling of being picked up and thrown over the water in plunge after plunge.

The little sea in this aquarium was not as grand as Hellas, of course, but sailing remained sailing. And from inside an aquarium with walls this clear, the view inside a cylinder was as if looking at and through a curved silvery mirror, everywhere broken up by the crisscrossing waves formed by the Coriolis current and the chiral wind, creating between them very complex patterns. It was as if the classic patterns of a physics class wave tank were here topologically warped onto the inside of a cylinder. Intersecting waves on this surface curved in non-Euclidean ways, a strange and lovely thing to see in all the mirrored silvers. And behind all the silvers lay blues. Inside the transparent shell of the aquarium, with the ocean also the sky, every silvery surface on the sunward side of the cylinder was backed or filled by a deep eggshell blue, while if one was looking away from the sun, the backing blue was an equally rich but much darker shade, almost indigo, and flecked here and there by the white pricks of the brightest stars. A floating town disrupted this cylindrical sea, but Genette spent most of the time on the water, sailing a trimaran at the fastest angles the winds offered.

On hearing Swan was there, Genette sailed into Pitcairn and picked her up. There she stood on the end of the dock, fizzing in her usual way—tall, arms crossed, hungry look in her eye. She glared down at the inspector’s sailboat suspiciously; it was sized for smalls, and Swan was just barely going to fit. Genette dismissed her suggestion to take out a larger boat, and placed her on the windward pontoon with her feet on the main hull, while he sat in the cockpit, holding a wheel that seemed to come from a much larger vessel. And there they were, talking as they skidded over the waves like a shearwater. With such a big weight to windward, Genette could really catch a lot of wind on the mainsail, and the bow of Swan’s pontoon knocked a lot of spray up into the blues.

Out getting banged on by the wind obviously pleased Swan. She looked around at things more than when Genette had last traveled with her. She looked slightly electrocuted, one might say. She had been on Earth for the reanimation, so no doubt that had made her happy. But there was also a new set to her mouth, a little chisel mark between her eyebrows.

“Wahram sent me to say you need to get out to a meeting on Titan,” she said. “It’s Alex’s group, and they’re meeting off the grid to discuss something important. Something about qubes. I’m going to go too. So can you tell me what this is all about?”

Buying a little time to think it over, Genette brought the boat about and had Swan change pontoons. Once set on the new course, a tug on the mainsheet tilted her upright. She grinned a little fiercely at this sailor’s evasion, shook her head; she would not be distracted.

Although in fact this shift had brought them on course to catch one of the waves breaking on the reef. Genette pointed this out, and together they watched the swells as Genette trimmed the sails for more speed. They skidded over the water in a broad turn that met the wave as it was rising on the reef; the trimaran was lifted and then caught by the wave, surfing across its face, falling more than sailing, and yet the wind on the top half of the sail served to keep them ahead of the break, if Genette could capture it right. Swan proved expert at providing a counterweight, leaning and shifting in response to the fluctuations of the ride.

Where the reef petered out, the wave lost its white teeth and laid back into a mere swell. After one last bump over the backwash of a crossing wave, they were only sailing again.

“Well done,” Swan said. “You must sail a lot.”

“Yes, I travel in aquaria when I can. So by now I’ve sailed most of them. Or iceboated them. When they’re frozen inside, you can get going like in a centrifuge.”

“I was just up in Inuit country myself, but it was summer and all the ice was gone. Except for the damn pingos.”

They sailed on for a while. Overhead their water-silvered sky bent through a smooth curve of blues from turquoise to indigo.

Swan said, “But back to this meeting. Wahram said it had something to do with some new qubes. So… do you remember that time we were in the Inner Mongoliaand I met those silly girls, and I thought they were people? And you thought they might be some strange qube people?”

“Yes, of course,” the inspector said. “They were.”

“Well, a strange thing happened to me on the way out here. I was lawn bowling with a young person in the Chateau Garden, and this kid was… trying to impinge on my attention, I guess I would call it, without actually saying very much. It was mostly in the play of the game, but also… it was like the long stare you sometimes get from wolves. There’s a thing wolves do when they’re on the hunt called the long stare. It’s unnerving to prey animals, to the point where some quit trying as hard to get away.”

Genette, familiar with the look and the technique, nodded. “And this person had a long stare.”

“So it seemed, yes. Maybe that was part of what gave me the creeps. I’ve had wolves look at me that way. I could see in my peripheral vision how different it was from an ordinary look. Maybe that was how a sociopath looks at people.”

“A wolf person.”

“Well, but I like wolves.”

“Perhaps like a qube,” Genette suggested. “Not like the ones on the Inner Mongolia, but not quite human either.”

“Maybe. When I talk about the long stare, I’m just trying to figure it out. Because it was unnerving. And then the way this kid was lawn bowling—as if it meant something.”

Genette regarded her, interested by this. “As if lawn bowling might be the tossing of balls at a target?”

“Exactly.”

“That’s what it is, yes?”

She shook her head, frowning at this.

Genette sighed. “Anyway, it should be perfectly easy to ask the Chateau Gardenfor a manifest.”

“I did that, and looked at all the photos. This lawn bowler wasn’t there.”

“Hmm.” Genette thought about it. “Can you share your qube’s records with me?”

“Yes, of course.”

She shifted from the pontoon to the cockpit, and Genette came up into the wind a bit. She leaned over and asked Pauline to transfer the photos she had already pulled. Genette inspected Passepartout’s little wristpad display.

“There,” Swan said, pointing to one photo. “That’s the one. And that’s the look I mean.”

The inspector studied the image: an androgynous face, an intent look. “It doesn’t really come through in a photo.”

“What do you mean? Look at that!”

“I am, but this person could be thinking of a calculus problem, or suffering a moment of indigestion.”

“No! It wasn’t like that in person. I think you should see if you can find this kid. If you can, you’ll see for yourself. And if you can’t, it gets kind of mysterious, doesn’t it? This person wasn’t on the manifest. So if you can’t find them, maybe the look will begin to mean more to you.”

“Maybe,” Genette said. This was the kind of break in a case that amateurs hoped for, which in reality seldom happened. On the other hand, it might be some kind of move on the part of the qubes. Some of the ones inhabiting humanoid bodies had behaved so oddly it was hard to know what they might or might not do.

The question now was how much Swan could be trusted, given how permanent her qube was, and how little was known about it. Not for the first time Genette was grateful that Passepartout was located in a wristpad that could be turned off, or taken off if necessary. Of course it was possible to ask Swan to turn off Pauline, as before. Secrecy from qubes could be achieved, even when they were stuck inside your head. It only had to be arranged. And on Titan the Alexandrines would be arranging for a sequestered conversation. It was clearly the next step if they were going to fold Swan into the new effort.

Genette watched her while thinking it over. “We need to talk with Wahram and the whole group involved with this. There are things you need to know, but the meeting there will be the best place to tell you.”

“All right,” she said. “Let’s go then.”