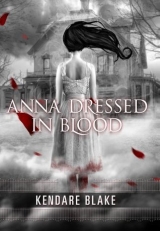

Текст книги "Anna Dressed in Blood"

Автор книги: Kendare Blake

Жанры:

Ужасы

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 2 (всего у книги 16 страниц)

CHAPTER THREE

The scenery changed fast once we crossed over into Canada, and I’m looking out the window at miles of rolling hills covered in forest. My mother says it’s something called boreal forest. Recently, since we really started moving around, she’s developed this hobby of intensely researching each new place we live. She says it makes it feel more like a vacation, to know places where she wants to eat and things that she wants to do when we get there. I think it makes her feel like it’s more of a home.

She’s let Tybalt out of his pet carrier and he’s perched on her shoulder with his tail wrapped around her neck. He doesn’t spare a glance for me. He’s half Siamese and has that breed’s trait of choosing one person to adore and saying screw off to all the rest. Not that I care. I like it when he hisses and bats at me, and the only thing he’s good for is occasionally seeing ghosts before I do.

My mom is staring up at the clouds, humming something that isn’t a real song. She’s wearing the same smile as her cat.

“Why the good mood?” I ask. “Isn’t your butt asleep yet?”

“Been asleep for hours,” she replies. “But I think I’m going to like Thunder Bay. And from the looks of these clouds, I’m going to get to enjoy it for quite some time.”

I glance up. The clouds are enormous and perfectly white. They sit deadly still in the sky as we drive into them. I watch without blinking until my eyes dry out. They don’t move or change in any way.

“Driving into unmoving clouds,” she whispers. “Things are going to take longer than you expect.”

I want to tell her that she’s being superstitious, that clouds not moving don’t mean anything, and besides, if you watch them long enough they have to move—but that would make a hypocrite of me, this guy who lets her cleanse his knife in salt under moonlight.

The stagnant clouds make me motion-sick for some reason, so I go back to looking at the forest, a blanket of pines in colors of green, brown, and rust, struck through with birch trunks sticking up like bones. I’m usually in a better mood on these trips. The excitement of somewhere new, a new ghost to hunt, new things to see … the prospects usually keep my brain sunny for at least the duration of the drive. Maybe it’s just that I’m tired. I don’t sleep much, and when I do, there’s usually some kind of nightmare involved. But I’m not complaining. I’ve had them off and on since I started using the athame. Occupational hazard, I guess, my subconscious letting out all the fear I should be feeling when I walk into places where there are murderous ghosts. Still, I should try to get some rest. The dreams are particularly bad the night after a successful hunt, and they haven’t really calmed down since I took out the hitchhiker.

An hour or so later, after many attempts at sleep, Thunder Bay comes up in our windshield, a sprawling, urban-esque city of over a hundred thousand living. We drive through the commercial and business districts and I am unimpressed. Walmart is a convenient place for the breathing, but I have never seen a ghost comparing prices on motor oil or trying to jimmy his way into the Xbox 360 game case. It’s only as we get into the heart of the city—the older part of the city that rests above the harbor—that I see what I’m looking for.

Nestled in between refurbished family homes are houses cut out at bad angles, their coats of paint peeling in scabs and their shutters hanging crooked on their windows so they look like wounded eyes. I barely notice the nicer houses. I blink as we pass and they’re gone, boring and inconsequential.

Over the course of my life I’ve been to lots of places. Shadowed places where things have gone wrong. Sinister places where things still are. I always hate the sunlit towns, full of newly built developments with double-car garages in shades of pale eggshell, surrounded by green lawns and dotted with laughing children. Those towns aren’t any less haunted than the others. They’re just better liars. I like it more to come to a place like this, where the scent of death is carried to you on every seventh breath.

I watch the water of Superior lie beside the city like a sleeping dog. My dad always said that water makes the dead feel safe. Nothing draws them more. Or hides them better.

My mom has turned on the GPS, which she has affectionately named Fran after an uncle with a particularly good sense of direction. Fran’s droning voice is guiding us through the city, directing us like we’re idiots: Prepare to turn left in 100 feet. Prepare to turn left. Turn left. Tybalt, sensing the end of the journey, has returned to his pet carrier, and I reach down and shut the door. He hisses at me like he could have done it himself.

The house that we rented is smallish, two stories of fresh maroon paint and dark gray trim and shutters. It sits at the base of a hill, the start of a nice flat patch of land. When we pull up there are no neighbors peeking at us from windows or coming out onto their porches to say hello. The house looks contained, and solitary.

“What do you think?” my mom asks.

“I like it,” I reply honestly. “You can see things coming.”

She sighs at me. She’d be happier if I would grin and bound up the stairs of the front porch, throw open the door and race up to the second floor to try and call dibs on the master bedroom. I used to do that sort of thing when we’d move into a new place with Dad. But I was seven. I’m not going to let her road-weary eyes guilt me into anything. Before I know it, we’ll be making daisy chains in the backyard and crowning the cat the king of summer solstice.

Instead, I grab the pet carrier and get out of the U-Haul. It isn’t ten seconds before I hear my mom’s footsteps behind my own. I wait for her to unlock the front door, and then we go in, smelling cooped-up summer air and the old dirt of strangers. The door has opened on a large living room, already furnished with a cream-colored couch and wingback chair. There’s a brass lamp that needs a new lampshade, and a coffee and end table set in dark mahogany. Farther back, a wooden archway leads to the kitchen and an open dining room.

I look up into the shadows of the staircase on my right. Quietly, I close the front door behind us and set the pet carrier on the wood floor, then open it up. After a second, a pair of green eyes pokes out, followed by a black, slinky body. This is a trick I learned from my dad. Or rather, that my dad learned from himself.

He’d been following a tip into Portland. The job in question was the multiple victims of a fire in a canning factory. His mind was wound up with thoughts of machinery and things whose lips cracked open when they spoke. He hadn’t paid much attention when he rented the house we moved into, and of course the landlord didn’t mention that a woman and her unborn baby died there when her husband pushed her down the stairs. These are things one tends to gloss over.

It’s a funny thing about ghosts. They might have been normal, or relatively normal, when they were still breathing, but once they die they’re your typical obsessives. They become fixated on what happened to them and trap themselves in the worst moment. Nothing else exists in their world except the edge of that knife, the feel of those hands around their throat. They have a habit of showing you these things, usually by demonstration. If you know their story, it isn’t hard to predict what they’ll do.

On that particular day in Portland, my mom was helping me move my boxes up into my new room. It was back when we still used cheap cardboard, and it was raining; most of the box tops were softening like cereal in milk. I remember laughing over how wet we were getting, and how we left shoe-shaped puddles all over the linoleum entryway. By the sound of our scrambling feet you would have thought a family of hypoglycemic golden retrievers was moving in.

It happened on our third trip up the stairs. I was slapping my shoes down, making a mess, and had taken my baseball glove out of the box because I didn’t want it to get water-spotted. Then I felt it—something glide by me on the staircase, just brushing past my shoulder. There was nothing angry or hurried about the touch. I never told anyone, because of what happened next, but it felt motherly, like I was being carefully moved out of the way. At the time I think I thought it was my mom, making a play-grab for my arm, because I turned around with this big grin on my face, just in time to see the ghost of the woman change from wind to mist. She seemed to be wearing a sheet, and her hair was so pale that I could see her face through the back of her head. I’d seen ghosts before. Growing up with my dad, it was as routine as Thursday night meatloaf. But I’d never seen one shove my mother into thin air.

I tried to reach her, but all I ended up with was a torn scrap of the cardboard box. She fell back, the ghost wavering triumphantly. I could see Mom’s expression through the floating sheet. Strangely enough, I can remember that I could see her back molars as she fell, the upper back molars, and that she had two cavities in them. That’s what I think of when I think of that incident: the gross, queasy feeling I got from seeing my mother’s cavities. She landed on the stairs butt first and made a little “oh” sound, then rolled backward until she hit the wall. I don’t remember anything after that. I don’t even remember if we stayed in the house. Of course my father must have dispatched the ghost—probably that same day—but I don’t remember anything else of Portland. All I know is, after that my dad started using Tybalt, who was just a kitten then, and Mom still walks with a limp on the day before a thunderstorm.

Tybalt is eyeing the ceiling, sniffing the walls. His tail twitches occasionally. We follow him as he checks the entirety of the lower level. I get impatient with him in the bathroom, because he looks like he’s forgotten that he has a job to do and instead wants to roll on the cool tile. I snap my fingers. He squints at me resentfully, but he gets up and continues his inspection.

On the stairs he hesitates. I’m not worried. What I’m looking for is for him to hiss at thin air, or to sit quietly and stare at nothing. Hesitation doesn’t mean a thing. Cats can see ghosts, but they don’t have precognition. We follow him up the stairs and out of habit I take my mom’s hand. I’ve got my leather bag over my shoulder. The athame is a comforting presence inside, my own little St. Christopher’s medallion.

There are three bedrooms and a full bathroom on the fourth floor, plus a small attic with a pull-down ladder. It smells like fresh paint, which is good. Things that are new are good. No chance that some sentimental dead thing has attached itself. Tybalt winds his way through the bathroom and then walks into a bedroom. He stares at the dresser, its drawers open and askew, and regards the stripped bed with distaste. Then he sits and cleans both forepaws.

“There’s nothing here. Let’s move our stuff in and seal it.” At the suggestion of activity, the lazy cat turns his head and growls at me, his green reflector eyes as round as wall clocks. I ignore him and reach up for the trap door to the attic. “Ow!” I look down. Tybalt has climbed me like a tree. I’ve got both hands on his back, and he has all four sets of claws snugly embedded in my skin. And the damned thing is purring.

“He’s just playing, honey,” my mom says, and carefully plucks each paw off of my clothing. “I’ll put him back in his carrier and stow him in a bedroom until we get the boxes in. Maybe you should dig in the trailer and find his litter box.”

“Great,” I say sarcastically. But I do get the cat set up in my mom’s new bedroom with food, water, and his cat box before we move the rest of our stuff into the house. It takes only two hours. We’re experts at this. Still, the sun is beginning to set when my mom finishes up the kitchen-witch business: boiling oils and herbs to anoint the doors and windows with, effectively keeping out anything that wasn’t in when we got here. I don’t know that it works, but I can’t really say that it doesn’t. We’ve always been safe in our homes. I do, however, know that it reeks like sandalwood and rosemary.

After the house is sealed, I start a small fire in the backyard, and my mom and I burn every small knickknack we find that could have meant something to a previous tenant: a purple beaded necklace left in a drawer, a few homemade potholders, and even a tiny book of matches that looked too well-preserved. We don’t need ghosts trying to come back for something left behind. My mom presses a wet thumb to my forehead. I can smell rosemary and sweet oil.

“Mom.”

“You know the rules. Every night for the first three nights.” She smiles, and in the firelight her auburn hair looks like embers. “It’ll keep you safe.”

“It’ll give me acne,” I protest, but make no move to wipe it off. “I have to start school in two weeks.”

She doesn’t say anything. She just stares down at her herbal thumb like she might press it between her own eyes. But then she blinks and wipes it on the leg of her jeans.

This city smells like smoke and things that rot in the summer. It’s more haunted than I thought it would be, an entire layer of activity just under the dirt: whispers behind peoples’ laughter, or movement that you shouldn’t see in the corner of your eye. Most of them are harmless—sad little cold spots or groans in the dark. Blurry patches of white that only show up in a Polaroid. I have no business with them.

But somewhere out there is one that matters. Somewhere out there is the one that I came for, one who is strong enough to squeeze the breath out of living throats.

I think of her again. Anna. Anna Dressed in Blood. I wonder what tricks she’ll try. I wonder if she’ll be clever. Will she float? Will she laugh or scream?

How will she try to kill me?

CHAPTER FOUR

“Would you rather be a Trojan or a tiger?”

My mother asks this while she’s standing over the griddle making us cornmeal pancakes. It’s the last day to register me for high school before it starts tomorrow. I know that she meant to do it sooner, but she’s been busy forming relationships with a number of downtown merchants, trying to get them to advertise her fortune-telling business and seeing if they’ll carry her occult supplies. There’s apparently a candle maker just outside of town that has agreed to infuse her product with a specific blend of oils, sort of a candle-spell in a box. They’d sell these custom creations at shops around town, and Mom would also ship them to her phone clientele.

“What kind of a question is that? Do we have any jam?”

“Strawberry or something called Saskatoon, which looks like blueberry.”

I make a sour face. “I’ll take the strawberry.”

“You should live dangerously. Try the Saskatoon.”

“I live dangerously enough. Now what’s this about condoms or tigers?”

She sets a plate of pancakes and toast down in front of me, each topped with a pile of what I desperately hope is strawberry jam.

“Behave yourself, kiddo. They’re the school mascots. Do you want to go to Sir Winston Churchill or Westgate Collegiate? Apparently we’re close enough for both.”

I sigh. It doesn’t matter. I’ll take my classes and pass my tests, and then I’ll transfer out, just like always. I’m here to kill Anna. But I should make a show of caring, to please my mom.

“Dad would want me to be a Trojan,” I say quietly, and she pauses for just a second over the griddle before sliding the last pancake onto her plate.

“I’ll go over to Winston Churchill then,” she says. What luck. I chose the douche-y sounding one. But like I said, it doesn’t matter. I’m here for one thing, something that fell into my lap while I was still fruitlessly casting about for the County 12 Hiker.

It came, charmingly, in the mail. My name and address on a coffee-stained envelope, and inside just one scrap of paper with Anna’s name on it. It was written in blood. I get these tips from all over the country, all over the world. There are not many people who can do what I do, but there are a multitude of people who want me to do it, and they seek me out, asking those who are in the know and following my trail. We move a lot but I’m easy enough to find if they look. Mom makes a website announcement whenever we relocate, and we always tell a few of my father’s oldest friends where we’re headed. Every month, like clockwork, a stack of ghosts flies across my metaphorical desk: an e-mail about people going missing in a Satanic church in northern Italy, a newspaper clipping of mysterious animal sacrifices near an Ojibwe burial mound. I trust only a few sources. Most are my father’s contacts, elders in the coven he was a member of in college, or scholars he met on his travels and through his reputation. They’re the ones I can trust not to send me on wild-goose chases. They do their homework.

But, over the years, I’ve developed a few contacts of my own. When I looked down at the scrawling red letters, cut across the paper like scabbed-over claw marks, I knew that it had to be a tip from Rudy Bristol. The theatrics of it. The gothic romance of the yellowed parchment. Like I was supposed to believe the ghost actually did it herself, etching her name in someone’s blood and sending it to me like a calling card inviting me to dinner.

Rudy “the Daisy” Bristol is a hard-core goth kid from New Orleans. He lounges around tending bar deep in the French Quarter, lost somewhere in his mid-twenties and wishing he were still sixteen. He’s skinny, pale as a vampire, and wears way too much mesh. So far he’s led me to three good ghosts: nice, quick kills. One of them was actually hanging by his neck in a root cellar, whispering through the floorboards and enticing new residents of the house to join him in the dirt. I walked in, gutted him, and walked back out. It was that job that made me like Daisy. It wasn’t until later on that I learned to enjoy his extremely enthusiastic personality.

I called him the minute I got his letter.

“Hey man, how’d you know it was me?” There was no disappointment in his voice, just an excited, flattered tone that reminded me of some kid at a Jonas Brothers concert. He’s such a fanboy. If I allowed it, he’d strap on a proton pack and follow me around the country.

“Of course it was you. How many tries did it take you to get the letters to look right? Is the blood even real?”

“Yeah, it’s real.”

“What kind of blood is it?”

“Human.”

I smiled. “You used your own blood, didn’t you?” There was a sound of huffing, of shifting around.

“Look, do you want the tip or not?”

“Yeah, go ahead.” My eyes were on the scrap of paper. Anna. Even though I knew it was just one of Daisy’s cheap tricks, her name in blood looked beautiful.

“Anna Korlov. Murdered in 1958.”

“By who?”

“Nobody knows.”

“How?”

“Nobody really knows that either.”

It was starting to sound like a crock. There are always records, always investigations. Each drop of blood spilled leaves a paper trail from here to Oregon. And the way he kept trying to make the phrase “nobody knows” sound creepy was starting to wear on my nerves.

“So how do you know?” I asked him.

“Lots of people know,” he replied. “She’s Thunder Bay’s favorite spook story.”

“Spook stories usually turn out to be just that: stories. Why are you wasting my time?” I reached out for the paper, ready to crumple it in my fist. But I didn’t. I don’t know why I was being skeptical. People always know. Sometimes a lot of people. But they don’t really do anything about it. They don’t really say anything. Instead they heed the warnings and cluck their tongues at any ignorant fool who stumbles into the spider’s den. It’s easier for them that way. It lets them live in the daylight.

“She’s not that kind of spook story,” Daisy insisted. “You won’t ask around town and get anything about her—unless you ask in the right places. She’s not a tourist attraction. But you walk into any teenage girls’ slumber party, and I guarantee you they’ll be telling Anna’s story at midnight.”

“Because I walk into a ton of teenage girls’ slumber parties,” I sighed. Of course, I suppose that Daisy really did, back in his day. “What’s the deal?”

“She was sixteen when she died, the daughter of Finnish immigrants. Her father was dead, he died of some disease or something, and her mom ran a boarding house downtown. Anna was on her way to a school dance when she was killed. Someone cut her throat, but that’s an understatement. Someone nearly cut her head clean off. They say she was wearing a white party dress, and when they found her, the whole thing was stained red. That’s why they call her Anna Dressed in Blood.”

“Anna Dressed in Blood,” I repeated softly.

“Some people think that it was one of the boarders that did it. That some pervert took a look at her and liked what he saw, followed her and left her bleeding in a ditch. Others say it was her date, or a jealous boyfriend.”

I took a deep breath to pull me out of my trance. It was bad, but they were all bad, and it was by no means the worst thing I’d ever heard. Howard Sowberg, a farmer in central Iowa, killed his entire family with a pair of hedge shears, alternately stabbing and snipping as the case allowed. His entire family consisted of his wife, his two young sons, a newborn, and his elderly mother. Now that was one of the worst things I’d ever heard. I was disappointed to get to central Iowa and discover that the ghost of Howard Sowberg wasn’t remorseful enough to hang around. Strangely enough, it’s usually the victims that turn bad in the afterlife. The truly evil move on, to burn or turn to dust or be reincarnated as dung beetles. They use up all their rage while they’re still breathing.

Daisy was still going on about Anna’s legend. His voice was growing lower and breathier with excitement. I couldn’t decide whether to laugh or be annoyed.

“Okay, so what does she do, now?”

He paused. “She’s killed twenty-seven teenagers … that I know of.”

Twenty-seven teenagers in the last half century. It was starting to sound like a fairy tale again, either that or the strangest cover-up in history. Nobody kills twenty-seven teenagers and escapes without being chased into a castle by a crowd holding torches and pitchforks. Not even a ghost.

“Twenty-seven local kids? You’ve got to be kidding me. Not drifters, or runaways?”

“Well—”

“Well, what? Someone’s pulling your chain, Bristol.” Bitterness grew in the back of my throat. I don’t know why. So what if the tip was fake? There were fifteen other ghosts waiting in the stack. One of them was from Colorado, some Grizzly Adams type who was murdering hunters on an entire mountain. Now that sounded like fun.

“They never find any bodies,” Daisy said in an effort to explain. “They must just figure that the kids ran away, or were abducted. It’s only the other kids who would say anything about Anna, and of course nobody does. You know better than that.”

Yeah. I knew better than that. And I knew something else too. There was more to Anna’s story than Daisy was telling me. I don’t know what it was, call it intuition. Maybe it was her name, scrawled out in crimson. Maybe Daisy’s cheap and masochistic trick really did work after all. But I knew. I know. I feel it in my gut, and my father always told me when your gut says something, you listen.

“I’ll look into it.”

“Are you going?” There was that excited tone again, like an overeager beagle waiting to have his rope thrown.

“I said I’ll look into it. I’ve got something to wrap up here first.”

“What is it?”

I briefly told him about the County 12 Hiker. He made some asinine suggestions on how to draw him out that were so asinine I don’t even remember them now. Then, as usual, he tried to get me to come down to New Orleans.

I wouldn’t touch New Orleans with a ten-foot pole. That town is haunted as shit, and all the better for it. Nowhere in the world loves its ghosts more than that city. Sometimes I worry for Daisy; I worry that someone will get wind of his talking to me, sending me out on hunts, and then someday I’ll have to be hunting him, some ripped-up victim version of him dragging his severed limbs around a warehouse.

I lied to him that day. I didn’t look into it any further. By the time I had gotten off the phone, I knew that I was going after Anna. My gut told me that she wasn’t just a story. And besides, I wanted to see her, dressed in blood.