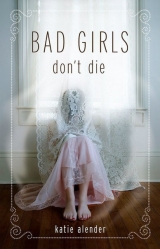

Текст книги "Bad Girls Don't Die"

Автор книги: Katie Alender

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 6 (всего у книги 15 страниц)

12

I felt like time had hiccupped forward two seconds and left me behind. Carter grabbed my hand, and I vaguely noticed that he pulled me through the courtyard. Lydia was on the other side of me like a yappy dog nipping at my heels.

“Don’t you know anything else?” he asked her, sounding irritated.

“They just told me to find Alexis!” she protested. “They kept paging her, but she didn’t answer.”

“The PA system in the library must be broken,” Carter said. “We didn’t hear.”

In the front office, Mrs. Ames came forward to meet us. She did a double take when she saw Carter holding my hand, but then she put her hand on my shoulder.

“Your father is okay,” she said. “He’s at St. Margaret’s hospital, and he’s going to be all right.”

Hearing that melted the steel rod that had been holding me up. I felt my legs go weak. If Carter hadn’t chosen that exact moment to squeeze my hand, I might have passed out.

“Where’s my mom?” I asked. “What about my little sister?”

“Your mother is at the hospital already, and your neighbor Mary Fuller is picking you and your sister up to drive you over there,” Mrs. Ames said.

“I can drive her to the hospital,” Carter offered.

“I’m afraid that’s not permissible, Carter,” she replied. “But thank you for offering. Alexis, come and sit down for a minute.”

Sit down? Who could sit down at a time like this? I know this is weird, but I felt like if I stopped panicking or worrying for a second, something terrible would happen—and it would be my fault.

I looked up at Carter, my brain loading up another round of frantic questions.

“You really should sit down,” he said.

I was outnumbered.

We followed Mrs. Ames into her office and I sank onto my usual spot on her sofa.

“What happened?” I asked. “Who called? Tell me what happened.”

Mrs. Ames looked directly into my eyes. “Your mother called. Your father was in an automobile accident, and he’s in the hospital, but he’s okay. It’s important that you go and be with your family, but it’s not because this is a life-or-death situation, do you understand?”

So that meant I should act like a grown-up, right?

“You don’t need to worry,” she repeated in her principal voice. She sat down at her desk. Her brown hair fell to her shoulders in soft waves that began together but went in all directions as they brushed her Surrey Eagles sweatshirt. It was the hair of a woman with no time to blow-dry. Mom would cut off a toe before she left the house with hair like that.

“It’s okay,” Carter said. “Your dad will be fine.”

I nodded. Nodding was easy. Things on the outside were easy. But inside I was a complete wreck. I didn’t know what to feel. I mean, I didn’t even really like my dad. But I didn’t want him dead…or even hurt.

I felt something in me slide, slide, slide. Like I’d been standing on a hill watching all of this happening to someone else, and slowly the ground was coming out from underneath me. The air seemed stuffy and unbearably hot.

“Can we go outside?” I asked.

“Mrs. Fuller will need to come into the office and sign you out,” Mrs. Ames said. “But we can wait for the car out front, if you want to.”

“She does,” Carter said, standing.

He did everything. He told Lydia, who’d been growing restless in the corner, to go back to class. He had the secretary bring me a glass of water. He carried my bag and made sure there were no ants on the bench where we sat down, and when we sat, he didn’t say anything, just looked for the car.

I was so glad he was there.

A car finally pulled up. It was our busybody kindly-old-lady neighbor from across the street, Mary. She went inside with Mrs. Ames. Carter opened the door for me and handed me my bag. He leaned down and looked at Kasey, who was slouched against the back driver’s side window, looking at us with wide eyes. Her arm was wrapped around her schoolbag as if it were a life preserver.

“Hi there,” he said, and she raised her hand and waved weakly.

“Kase, this is Carter,” I said. “Carter, this is Kasey, my little sister. She goes to Surrey Middle.”

“Nice to meet you,” he said. Kasey nodded, staring up at him a little dumbly. I hoped he didn’t think she was slow or something. She was just in shock.

Mary came back out to the car, mercifully silent. She’s usually one of those people who can talk until you want to toss yourself off a bridge.

“Thanks,” I told Carter. “Thanks for—”

He shook his head. For a moment I thought he might kiss me, but he just touched my forehead with his hand. It was the softest gesture, like a feather brushing over my skin. “Call me,” he said, scribbling his phone number on a torn-out page of his spiral notebook and thrusting it into my hand. “Especially if you need anything.”

“Okay,” I said, still reeling from his touch. Carter closed the door and the car pulled away.

“He’s nice,” Kasey said at last.

Neither of us said another word during the entire drive to the hospital.

Mom was inside, her purse slung heavily over her shoulder, chewing on her thumbnail and pacing back and forth across eight worn squares of linoleum. When she saw us, she came hurrying over and pulled us into a hug.

“Your father’s fine,” she said. “He needs medical treatment, but he’ll be okay.”

Kasey pulled away and looked at Mom with glassy

eyes.

“What happened?” she asked.

Mom took a deep breath. “He was on his way to work, and something went wrong with the car. He veered off the side of the road and hit a tree, but he wasn’t going very fast.” She pushed her hair back off her face. “Luckily, he was going uphill.”

“So he’s okay?” Kasey asked.

“Yes, he’s probably got a broken leg and some broken ribs and some other internal…problems.” She patted Kasey’s shoulder. “But yes, he’s okay, thank God.”

Mom went on about physical therapy and cuts and scratches and medical stuff. I sat down on a smooth plastic chair and wrapped my hands around the metal armrests. They felt cold and clean and solid on my skin.

I’d never been in an emergency room before. It was a lot like the ones on TV—the linoleum floor shone under the buzzing fluorescent lights. Everything looked polished and sterile. Even the smells were disinfected– sharp hints of alcohol and bleach.

As I sat there and watched the thick plastic hands of the clock tick forward, my thoughts turned pessimistic. So what, Dad was going to have to stay home from work? Who would take care of him? How would we pay our bills? Were we just supposed to sit here and stare at the sick people coming in and out all day? Did people really do that?

I felt nauseous and sticky and angry. I longed for the splintered cushions and exposed foam of the library sofa, the soft, sandy sound of Carter’s voice. I remembered his fingers floating against my skin, and the thought made my throat feel tight.

The voices around us melted into a sickening murmur. I thought I might implode. But Kasey broke first.

“I have to go outside,” she said, standing up.

“I’ll go with you,” I said. Mom nodded vaguely.

The sun made us both squint as we walked out through the double doors.

“Can we just go home?” she asked.

“I wish,” I said. “We’re supposed to be here for Dad.”

Kasey stamped her foot on the sidewalk and let out a little grunt. “If one of us was in the hospital, he wouldn’t come,” she said.

“Yes he would,” I said.

“I want to go home,” she said.

“I know, Kase,” I sighed.

“Don’t you?”

“Sure. Whatever.” I didn’t have the energy to be reassuring.

Kasey crossed her arms in front of her. “I’ll walk if Mom won’t drive us,” she said. “Mom can’t leave,” I said. “Then let’s just go.”

“Be realistic,” I said. “We have to ask. Wait here, I’ll be right back.”

Mom was deep in conversation with Mary, so she just nodded and waved me away. Mary had started the story about her cousin who was killed in World War II. Anyone who’s lived in our neighborhood more than three weeks has heard it like forty times. It takes roughly thirty-five minutes, start to finish, and she can modify it to fit any occasion—birthdays, Christmas, Halloween….

“See you later,” I said, and walked out before Mom could say no. I didn’t want to be there any more than Kasey did.

13

The walk to the house was far —almost two miles, and it was hot. The bright sun had already baked off any of the morning’s autumn coolness. Neither of us complained, though—we were too glad to be going home.

We were hit by a blast of cool air when we passed through the front door. Mom must have left the air conditioner on when she left for work, which is like the worst sin you can commit in the Warren household. There are starving children in Africa, and you have the nerve to leave the air conditioner running all day?

We turned all moony for a minute, dropped our bags in the front hall, held our arms out and spun in slow circles under the vents. Heavenly. Kasey shook her hair wildly.

I checked my watch. It was only ten thirty, and I felt like I’d lived at least a full day’s worth of excitement.

“I think I’ll take a nap or something,” Kasey said. “I didn’t sleep so great last night.”

That made two of us.

She headed upstairs, and I flipped the air conditioner power switch to OFF, then went to the living room and sank into Dad’s recliner. If I closed my eyes and concentrated, I could smell the lingering aroma of his aftershave. I thought about him, alone in his room at the hospital. Did he feel lonely and sorry, unloved? What if he died and that chair was the only thing we had left that smelled like him? I breathed in again but couldn’t pick up the scent. Guilt flooded over me and left me feeling empty and scared and horribly selfish.

But as I reclined in the overstuffed chair, my relief was overwhelming. We would rest now and walk back to the hospital later, when it was cooler, and the sunlight wasn’t harsh and colorless and raw. A light breeze would be blowing, and we could stop at the grocery store on the way and buy flowers.

Gradually, a dream floated in and took over.

The little girl in the fancy dress—the one from my story.

She’s backed into a corner, crying. A crowd of kids has gathered around her, and I am one of the crowd. We have planned this for a week, now—since the day we saw her wandering through the graveyard with her doll, and Mildred told us that was a sure sign she was a witch.

We can’t have a witch in our town.

We close in.

The girl pushes through the group and runs. We run after her, shouting war cries, down an empty road. Our feet pound against packed dirt, sending up clouds of dust. We run for a long time. Finally, a house comes into view.

My house.

But it’s not my house in this dream.

The little girl is scrambling up the oak tree, desperately hauling herself from branch to branch, trying to reach the open window on the second story of the house.

I don’t want to do this, but I can’t stop myself. I reach down and scoop up a pebble from the ground. My hand reaches back, then sends it flying up at her.

“Cuckoo!” the girls are shouting. “Climb your tree, cuckoo bird! Fly away, cuckoo!”

The girl in the tree wails as she climbs higher and higher. Gradually, the constant stream of pebbles slows. The game isn’t fun anymore.

But then the biggest girl says, “Scare away the cuckoo bird!” and drops one last pebble into my hand. I take aim and throw it.

It hits the girl’s hand just as she reaches for another branch.

And she falls – a long, long fall.

She hits the ground and lies horribly still, and time seems to grind to a halt.

No one says a word.

“Go, Patience,” the big girl says. “Go wake her up.” I don’t want to.

“You threw the last one!” someone says. They are all urging me on now, scolding me and telling me it’s my fault.

I take a step toward the body on the ground. Surely she’s only sleeping? “Sarah,” I say.

I go closer, and walk around her to see her eyes. They are wide open. A trickle of blood drips from the side of her gaping lips. She is dead.

Next to her is the precious doll, whose hair is still clutched in Sarah’s hand. I step closer—

And suddenly the doll’s eyes pop open, bright green and glowing.

I woke with a breathless cough and looked at the clock—twelve thirty.

I’d been asleep for two hours, and the air conditioner had been blasting the entire time. The house was so cold I could practically see my breath. I hurried to turn off the air conditioner, goose bumps erupting on my arms.

Problem: I’d turned it off two hours ago. Still groggy from my nap, I stood and stared at the thermostat, hoping something would happen.

Nothing did, of course.

Great. Now the air conditioner was wonky. Mom and Dad would assume that Kasey and I turned it on when we got home and somehow broke it.

I pried the plastic cover away. The little blue arm stood at seventy-five, but the thermometer read fifty-four degrees. So even if it wasn’t off, it wasn’t supposed to be running.

The cold was unbearable. I ran upstairs and peered through Kasey’s bedroom door. She was asleep, little puffs of foggy breath escaping from her mouth. It was too cold for just a T-shirt.

The dolls seemed to stare in disapproval, and I knew if Kase woke up she’d probably flip out and spend the next six months paranoid that I was going to mess with her stuff when she wasn’t looking. But the last thing we needed was for her to get a horrible flu from sleeping in the freezing cold. I went just as far as the closet, to get a blanket.

The shelves in my sister’s closet (like the rest of her bedroom) were an absolute disaster. Books, jewelry, shoes, magazines, her old Snoopy phone that had turned yellow with age, all piled on top of one another. The pink blanket she used in the winter rested on the bottom shelf, with her backpack leaning up against it. As I pulled on the blanket, the backpack tipped over, spilling out a fan of multicolored folders.

I reached down to gather them, when I caught a glimpse of one of the covers.

my ancestors, it read. by mimi laird.

I looked at the next one. my ancestors, benji byerson. my ancestors, jennilynn woo. my ancestors, evan litchfield.

“What are you doing?”

The voice scared me so much that I dropped the stack of reports.

I just stared at her. “I came in to cover you up, but…why do you have everyone else’s projects?”

She gave me a look that said pretty plainly that she didn’t think it was my business.

“I’m a student grader,” she said at last.

“A what?”

“It’s new.” Kasey yawned and scooted to the edge of the bed. “Don’t bother with the blanket; I’m awake.” She followed my gaze to the papers on the floor. “I’ll get those later,” she said.

I was kind of surprised she hadn’t wigged out about me being so close to her dolls without supervision.

But she didn’t look anywhere near freaking out. And if she wasn’t going to freak out, I wasn’t going to either.

“There’s something wrong with the thermostat. Come help me check out the circuit breaker,” I said.

Kasey followed me downstairs and into the garage.

The cold had seeped under the kitchen door and even the garage was chilly. If Mom showed up now we’d be grounded until college. How long would it take to warm up the house if we opened all the windows? Then Mom would never know…until the electric bill showed up.

Built into the wall behind the garage door was a metal cabinet. Opening it revealed about thirty chunky black switches. Kasey leaned in to look at them.

“What are those?”

“Fuses,” I said.

“Which one is for the air conditioner?” Kasey asked.

I studied the little map at the top of the cabinet. Third down on the left, the little square was labeled “A/C.”

“This one,” I said, flipping the switch. “Go see if that worked.”

Kasey ran inside. A second later she came huffing and puffing back. “Nope,” she panted.

I stared at the rest of the circuits. “Okay,” I said. “Stay here and flip this switch when I tell you to.”

I went inside to the thermostat and looked at the little red light in the corner. “Flip it!” I called.

The red light went dark.

“Flip it back!” I called.

The light came back on. Then off, then on, then off, and on again. But none of that mattered, because the whole time, cold air never stopped blowing through the vent.

Kasey came in from the garage, shivering. “No luck?”

“No,” I said, my teeth chattering. “We’re going to get in sooo much trouble.”

“So what else is new?” Kasey said. She approached the thermostat and grabbed the switch, moving it back and forth. I almost told her to stop because I was afraid the stupid thing would break off.

“I’m freezing,” Kasey said under her breath. “Turn off, turn off”

Midflip, the air conditioner turned off. We stood in confused silence.

“Huh,” I said. “Weird.”

“I didn’t do anything!” Kasey snapped.

“Did I say you did?” I asked, going back into the kitchen. “Jeez.”

She stomped up the stairs, leaving me alone. I pulled a string cheese and a few pieces of sliced turkey out of the fridge and stood in the kitchen eating, just kind of looking around.

I looked at the garage door and then down at the floor. The light gray rag rug had dark smudges on it. Our footprints.

I lifted my foot and looked at the bottom of my sock.

It was covered in a fine dusting of grimy-looking dirt.

Just like the dirt I’d seen on Kasey’s sock that morning.

So she’d been in the garage?

At six thirty in the morning?

…Why?

The contact sheet from my earlier darkroom session was completely dry. I counted down to the fifth row of negatives and over three, to the half-ruined, half-in-focus picture. I put the negative into a little frame, checked the focus, then set a piece of photo paper down and hit the timer.

After fifteen seconds I slipped the paper into the developer and stood back to watch the image emerge.

But there wasn’t an image. Unless the whole paper immediately turning black counts as an image.

I pulled that page out and rinsed it clean before dropping it in the trash.

I set another piece of paper down and turned the timer on for five seconds, figuring it might be underexposed, but at least I would have a better idea of what time to use.

But no. This one turned black too. A panicky feeling started to rise up inside me as I looked at the package of photo paper. There were two black plastic bags with fifty sheets each; only the top one should have been unsealed. But they were both open. And the stacks of paper weren’t neat and even—they were irregular and off-center.

All of my paper had been exposed.

A package like this cost sixty dollars. With my current weekly allowance of twenty dollars, that meant three weeks of savings down the drain. And three weeks of more saving before I could even afford another package.

Three weeks without developing photos?

I started to feel kind of sick.

I’d told my sister a trillion times not to touch my stuff, not to even go into the darkroom, and she refused to listen.

Kasey was guilty. She had to be.

After a few deep breaths I went to confront my sister. My hands shook as I stalked down the hall and pounded on her door.

Stay calm, I told myself. Be mature.

She opened it, blue eyes wide.

“What?” she asked.

I took a long breath through my nose. “Just…tell me…why.” “Huh?”

My calm exterior shattered like a lightbulb dropped from a third-floor window. “Why did you do it, Kasey?

What did I do to you? I try so hard to be nice to you when nobody else even wants to be your friend, and you—”

Her hands flew up to her cheeks, which flushed pink. “Lexi!” she cried, dismayed.

I took a step back. “Why, Kasey?!”

“I didn’t do anything,” she said. “I swear I didn’t. I don’t even know what happened. I heard a noise and then all I remember is having the weirdest dream and then I was at school and they said come to the office because of Dad and I saw all the reports on Ms. Lewin’s desk and later they were in my bag—”

“What?”

Her face fell slack, her jaw hanging slightly open, her breath ragged.

“What are you talking about, Kase?”

She shook her head and stared at the floor.

“I’m talking about my photo paper. Someone ruined it. All of it.”

“It wasn’t me,” she said in a tiny voice.

“But wait—you stole those reports from school? I thought you said you were a student grader.”

“No!” she wailed. “I told you, I didn’t…I mean, I guess I took them, but I didn’t mean to. I just looked in my bag and found them there.”

“You’re saying someone framed you?” I asked.

“I don’t know. I guess so.”

Knowing how spiteful kids could be, it was a serious possibility. “Did you see anyone near your bag?” “I don’t know!” she said.

My patience was paper-thin. “Kasey, either you did, or you didn’t.”

“Maybe!” she said. “I mean, I don’t remember. But it had to be someone, right?”

Someone. More like Mimi Laird, or one of her snotty little friends. I didn’t say it out loud, though, because Kasey seemed traumatized enough.

I sighed. “You’re going to have to give them back.”

“I can’t!” she wailed. “I’ll get expelled!”

“Teachers understand mean kids, Kase,” I said. “You just have to do it soon so it doesn’t look any weirder.”

“Will you help me? I’m tired,” she said pitifully. “I didn’t sleep very much last night.”

I didn’t point out that she’d just taken a two-hour power nap.

A thought occurred to me. “Yeah, so…why were you in the garage this morning?”

Her nose wrinkled. “I wasn’t in the garage.”

“When I saw you in the hall, your socks were dirty—” I began.

“In the hall?” she asked. “I didn’t see you in the hall this morning.”

I stared at her.

“What are you talking about, Lexi? I don’t understand.”

I didn’t understand either. But I did understand that all of these bizarre things were starting to add up and make me feel like I was going crazy. After all, what was that old saying? The common link between all your problems is you?

What if I was losing it?

“I’m going for a walk,” I said, going into my room to get my house key. “Can I come?”

“No!” I said. “I just want to be by myself for a while.”

“No fair,” she whined.

“You just stay here,” I said. “And try to figure out how you’re going to explain to your teacher that you stole everybody’s reports.”

“I didn’t!” she yelled. “I didn’t steal anything! Someone put them in my bag!”

Then she ran into her room and slammed the door.

At least she wasn’t insisting on coming.

I went downstairs and out the front door, locking it as I left. Out of guilt, I glanced up at Kasey’s windows to see if she was looking down at me.

She was.

I pulled my eyes away from her and glanced at the oak tree, trying to forget its horrible role in my dream.

That’s when I noticed the lines of the wood, the jagged edges of long-since-removed limbs, the soft overgrowth of bark on several of the scars left behind by pruning or broken branches.

The tree I’d drawn the night before—it was this tree. This exact tree, down to a tuft of grass growing out of a tiny hollow about six feet off the ground.

I had to get out of there. But I could think of only one place to go.

I hurried down the front walk, toward the street.

By the time I reached the school, most of the parking lot was empty. A few stragglers stood by their cars in small groups, talking. A crowd of kids waited miserably at the bus loop for their late bus. At the sight of the brick building, my body tensed, the way it does at 7:58 every weekday morning. But it was better than being surrounded by things that made me feel like I was coming completely undone.

One girl looked at me strangely. When I walked past her, she moved forward like she was going to say something, but her friend touched her arm and they both turned away.

As I passed the gym, a mob of cheerleaders emerged from the band room and went by me, chattering like first graders at a crosswalk. They weren’t wearing uniforms, but their white-ribboned ponytails and packlike formation gave them away.

A couple of them looked at me and whispered, heads bowed together like horses nuzzling.

Megan Wiley was the last to exit. She carried a notebook and studied the papers inside it so intently that she almost walked right into me.

“Sorry,” she muttered, and then looked up. When she saw me, she took an involuntary step backward.

I averted my eyes, waiting for her to make a quick retreat into the gym after her minions, but she didn’t. Instead, when I glanced up, she was looking at me.

“How’s your dad?” she said.

The question was beyond unexpected. “Um, all right.”

“Lydia told everyone you fainted,” she said. With a shudder, she added, “Then she said your dad was probably going to die.”

I rolled my eyes and shook my head. For some reason my mouth felt like it was full of straw. “He’s okay,” I said. “Just broken bones, bruised organs. Limbs, ribs, that kind of thing.”

The conversation could have ended there, but Megan swallowed hard. “I just…My mom died in a car accident when I was a baby,” she said. “So I was really worried.”

Wow.

“Wow,” I said. What else could I say? The things you don’t know about people. “I’m sorry.” “Well, I don’t remember her, so…” “Still,” I said. Yikes.

“I live with my grandmother,” she said, and then her eyes flickered longingly toward the door where all of her friends had gone.

“But thanks for asking,” I said.

“I’m glad she’s okay.”

“No, it was… he. It was my dad,” I said.

She blushed, her perfect cheeks turning a lovely rose color. “I mean—I knew that, sorry.”

“Well,” I said, wishing for a sinkhole or something to swallow me up.

We stood there, up to our ankles in awkwardness.

“Thanks,” I said at last.

She smiled a tight-lipped smile and ducked into the gym. Huh.

I stood there for a second. Then without warning the door opened, and Megan stuck her head out.

“If you’re looking for Carter Blume, I saw him talking to Mr. Makely about five minutes ago,” she said.

My expression was apparently so shocked that it was funny, because Megan laughed. It was a short, self-conscious laugh, but it wasn’t mean or anything.

“See you,” she said, and disappeared. This time I hurried away so she couldn’t surprise me again.

Mr. Makely stood outside the library for twenty minutes after school ended every day. I’d probably have him for physics next year. He gave me a strange look as I entered the courtyard, and I got this weird, uncomfortable feeling that everyone thought my dad was dead. It made my heart beat funny for a second just to think about it. Carter wasn’t there, so I headed toward the student parking lot.

When I got there, the first thing I saw was Carter in his car, studying his iPod. I stopped suddenly as it hit me—what was I doing? Why had I run straight to Carter? I hardly even knew him, and here I was, following him around after school like a lovesick loser.

The skin around my jaw and ears felt tight, and my eyes started to burn. I wondered how fast I could get someplace else. Just somewhere he wouldn’t see me as he drove away. I scanned the parking lot and saw only low shrubs and a few cars that were all too far away to dash for.

I had no choice but to stand there and wait for him to notice me. He did a double take, then got out of the car and walked over.

“Hi,” he said, his voice a question.

I looked at him, and the “wanting to crawl under a rock and die” feeling intensified. “How’s your dad?” “He’s okay.”

Carter looked at me. “How are you?” Amazing how suddenly there was no easy answer to that question.

“I’m fine,” I said.

He just looked at me and shook his head. “No you’re not.”

That made me laugh, but laughing made tears spring to my eyes. “I know,” I said.

He didn’t say anything else. He held his hand out like I should take it.

“You don’t understand,” I said. “I think I’m losing my mind.”

He looked at the sky and then at the ground. “I understand,” he said.

And then I was engulfed in his arms and his smell, laundry detergent and shampoo and all that was clean. I closed my eyes and leaned against him and let everything go.