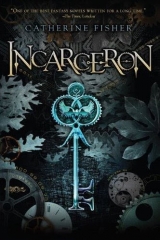

Текст книги "Incarceron"

Автор книги: Kathryn Fisher

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 8 (всего у книги 19 страниц)

Finn nodded. They all knew that the remains of any dead creature vanished overnight; that

Incarceron sent its Beetles out instantly and collected the raw material for recycling.

Nothing was ever buried here, nothing burned. Even those of the Comitatus who had been killed were left, wrapped in their favorite possessions, decked with flowers, in a place by the abyss. In the morning, they were always gone.

To their surprise Attia spoke. "My people knew this. For a long time now the lambs have been like this, and the dogs. Last year, in our group, a child was born. Its left foot was made of metal."

"What happened to it?" Keiro asked quietly.

"The child?" She shrugged. "They killed it. Such things can't be allowed to live."

"The Scum were kinder. We let all sorts of freaks live."

Finn glanced at him. Keiro's voice was acid; he turned and led the way through the wood.

But Gildas didn't move. Instead he said, "Don't you see what it means, fool boy? It means the Prison is running out of organic matter ..."

But Keiro wasn't listening. He lifted his hand, alert.

A sound was rising in the wood. A low whisper, a rustling breeze. Tiny at first, barely raising the leaves, it stirred Finn's hair, Gildas's robe.

Finn turned. "What is it?"

The Sapient moved, pushing him on. "Hurry. We must find shelter. Hurry!"

They ran between the trees, Attia always at Finn's heels. The wind grew rapidly. Leaves began to lift, swirl, fly past them. One nicked Finn's cheek; putting his hand up to the sudden sting he felt a cut, saw blood. Attia gasped, her hand protecting her eyes.

And all at once they were in a blizzard of metal slivers, the leaves of copper and steel and silver a razor-sharp whirlwind in the sudden storm. The wood groaned and bent, twigs cracked with snaps that rang in the invisible roof.

As he ran, ducking and breathless, Finn heard the roar of the storm like a great voice. It raged at him, picked him up and threw him; its anger crashed him against the metal trees, it bruised him and beat at him. Stumbling, he knew the leaves were its words, arrows of spite, that Incatceron was taunting him, its son, born from its cells, and he stopped, bent over, gasping, "I hear you! I hear you! Stop!"

"Finn!" Keiro yanked him down. He slid, the ground giving way, crumpling into a hollow between the tangled roots of some vast oak.

He landed on Gildas, who shoved him off. For a moment each of them caught breath, listening to the deadly leaves slicing the air outside, the whine and hum. Then Attia's muffled voice came from behind.

"What is this place?"

Finn turned. Behind them he saw a dull rounded hollow, seamed deep under the steel oak. Too low to stand up in, it extended back into darkness. The girl, on hands and knees, crept inside. Foil leaves crackled under her; he smelled a musty, odd tang, saw that the walls sprouted fungi, contorted, spore-dusted masses of flabby growth.

"It's a hole," Keiro said sourly. He drew his knees up, brushed litter from his coat, and then looked at Finn. "Is the Key safe, brother?"

"Of course it is," Finn muttered.

Keiro's blue eyes were hard. "Well, show me."

Oddly reluctant, Finn put his hand into his shirt. He drew the Key out, and they saw the crystal glimmer in the dimness. It was cold, and to Finn's relief, silent.

Attia's eyes went wide.

"Sapphique's Key!"

Gildas turned on her. "What did you say?"

But she wasn't looking at the crystal. She was staring at the picture scratched meticulously onto the back wall of the tree, smeared by centuries of dirt and overgrown by green lichen, the image of a tall, slim, dark-haired man sitting on a throne, in his upheld hands a hexagonal slot of darkness.

Gildas took the Key from Finn. He slotted it into the aperture. Instantly it began to glow; light and heat burned from it, showing them one another's dirty faces, the slanting cuts, brightening the furthest recesses of the hollow.

Keiro nodded. "We seem to be going the right way," he muttered.

Finn didn't answer. He was watching the Sapient; the glow of awe and joy on the old man's face. The obsession. It chilled him to the bone.

14

We forbid growth and therefore decay. Ambition, and therefore despair. Because each is only the warped reflection of the other. Above all, Time is forbidden. From now on nothing will change.

-King Endor's Decree

"I don't think you'll be wanting all this junk." Caspar picked a book out of the pile and opened it. He gazed idly at the bright illuminated letters. "We have books at the Palace. I never bother with them."

"You do surprise me." Claudia sat on the bed and gazed around hopelessly at the chaos.

How could she have so many possessions? And so little time!

"And the Sapienti have thousands." He tossed it aside. "You are so lucky, Claudia, that you never had to go to the Academy. I thought I'd die of dullness. Anyway, aren't we going out with the hawks? The servants can do all this. It's what they're for."

"Yes." Claudia was biting her nail; she realized, and stopped.

"Are you trying to get rid of me, Claudia?"

She looked up. He was watching her, his small eyes fixed in that nerveless stare. "I know you don't want to marry me," he said.

"Caspar ..."

"It's all right, I don't mind. It's a dynastic thing, that's all. My mother's explained it. You can have any lovers you like, after we've had an heir. I certainly will."

She stared at him in disbelief. She couldn't sit still; she jumped up and paced the disrupted room. "Caspar, listen to yourself!" Have you ever thought about what sort of life we'll have together, in that marble mausoleum you call a palace? Living a lie, a pretense, keeping false smiles on our faces, wearing clothes from a time that never existed, posing and preening and aping manners that should only be in books? Have you thought about that?"

He was surprised. "It's always been like that."

She sat next to him. "Have you never wanted to be free, Caspar? To be able to ride out alone one spring morning and set off to see the world? To find adventure, and someone you can love?"

It was too much. She knew it as soon as she had said it. Too much for him. She felt him stiffen and frown, and he glared at her. "I know what all this is about." His voice was harsh.

"It's because you'd have rather had my brother. The saintly Giles. Well, he's dead, Claudia, so forget about him." Then his smile came back, sly and narrow. "Or is this about

Jared?"

"Jared?"

"Well, it's obvious, isn't it? He's older, but some girls like that."

She wanted to slap him, to get up and slap his sniggering little face. He grinned at her.

"I've seen how you look at him, Claudia. Like I said, I don't mind."

She stood, stiff with anger. "You evil little toad."

"You're angry. That proves it's true. Does your father know about you and Jared, Claudia?

Should I tell him, do you think?"

He was poison. He was a lizard with a flicking tongue. His smirk was acid. She bent and put her face into his and he moved back.

"If you mention this again, to me, to anyone, I will kill you. Do you understand, my lord

Steen? Myself personally, with a dagger through your weak little body. I will kill you like they killed Giles."

Trembling with wrath she marched outside and slammed the door with a clap that rang down the corridor. Fax, the bodyguard, was lounging outside. As she passed him he stood, with an insolent slowness, and as she ran beneath the portraits to the stairs, she felt his eyes on her back, the cold smile.

She hated them.

All of them.

How could he say that!

How could he even think it! Thundering down the stairs, she crashed through the double doors, maids scattering before her, her mood like thunder. Such a filthy lie! Against Jared! Jared, who would never dream, never even think of such a thing!

She screamed for Alys, who came running. "What's wrong, lady?"

"My riding coat. Now!"

While she waited she fumed, pacing, staring through the open front door at the eternal perfection of the lawns, the blue sky, the peacocks practicing their eerie cries.

Her anger was warm and a comfort. When the coat came she flung it around her, snapped, "I'm riding out."

"Claudia ... There's so much to do! We leave tomorrow."

"You do it."

"The wedding dress ... the final fitting."

"You can tear it to shreds as far as I'm concerned." Then she was gone, running down the steps and across the courtyard, and as she ran, she looked up and saw her father, standing in the impossible window of his study that didn't exist, wasn't even there.

He had his back to her, was talking to someone. Someone in the study with him? But no one ever went in there.

Slowing, she watched for a moment, puzzled. Then, afraid he'd turn around, she hurried to the stables and found Marcus already saddled, pawing the ground with impatience.

Jared's horse was ready too, a lean rangy creature called Tam Lin, which was probably some secret Sapient jest she'd never understood.

She looked around. "Where's the Wise One?" she asked Job.

The boy, always tongue-tied, muttered, "Gone back to the tower, lady. He forgot something."

She stared at him. "Job, listen to me. You know everyone on the estate?"

"Pretty much." He swept the floor hastily, raising clouds of dust. She wanted to tell him to stop, but that would have made him even more nervous, so she said, "An old man called

Bartlett. Pensioned off, a retainer of the Court. Is he still alive?"

He raised his head. "Yes, my lady. He has a cottage out on Hewelsfield. Just down the lane from the mill."

Her heart thudded. "Is he ... Is his mind still clear?"

Job nodded, and managed a smile. "He's razor-sharp, that one. But he doesn't say much, not about his days at Court. He just stares if you ask him."

Jared's shadow darkened the doorway and he came in slightly breathlessly. "Sorry, Claudia."

He swung himself up into the saddle, and as she put her foot in Job's linked hands, she said quietly, "What did you forget?"

His dark eyes met hers. "A certain object that I didn't want to leave unguarded." His hand moved discreetly to his coat, the high-necked Sapient robe of dark green.

She nodded, knowing it was the Key.

As they rode off she wondered why she felt so oddly ashamed.

THEY MADE a fire from the dried fungi and some snapping powder from Gildas's pack and cooked the meat while the whirlwind raged outside. No one spoke much. Finn was shivering with cold, and the cuts on his face stung; he sensed that Keiro was still weary too. It was hard to tell about the girl. She sat slightly apart, eating quickly, her eyes watching and missing nothing.

Finally Gildas wiped greasy hands on his robe. "Were there any signs of the inmates?"

"The sheep were roaming," Keiro said carelessly. "Not even a fence."

"And the Prison?"

"How should I know? Eyes in the trees probably."

Finn shivered. His head felt echoey and strange. He wanted them to sleep, to fall asleep so he could get the Key out again and talk to it. To her. The girl Outside. He said, "We can't move on, so we may as well rest. Don't you think?"

"Sounds good," Keiro said lazily. He arranged his pack against the back of the hollow.

But Gildas was staring at the image carved in the tree trunk. He crawled closer, reached out, and began to rub at it with his veined hands. Curls of lichen fell. The narrow face seemed to emerge from dinginess and the green fur of moss, its hands holding the Key so carefully drawn, they seemed real. Finn realized that the Key must be linking into some circuitry in the tree itself and for a moment a blur of vision caught him off guard, a sense that the whole of Incarceron was a great creature in whose entrails of wire and bone they crept.

He blinked.

No one seemed to have noticed, though the girl was staring at him. Gildas was saying, "He's leading us along the way he took. Like a thread through the labyrinth."

"So he left his own picture?" Keiro drawled.

Gildas frowned. "Obviously not. This is a shrine, created by the Sapienti who have followed him. We should find other signs on the way."

"I can't wait." Keiro rolled himself over and curled up.

Gildas glared at his back. Then he said to Finn, "Take the Key out. We need to take care of it. The way may be longer than we think."

Thinking of the vast forest outside, Finn wondered if they would wander in it forever.

Carefully he reached up and removed the Key from the hexagon; it came away with a slight click, and instantly the hollow was dim and the whistling splinters of foil blurred the distant Prison lights.

Finn was stiff and uncomfortable, but he kept still, listening. After a long while he knew by the old mans harsh breathing that Gildas was sleeping. He wasn't sure about the others.

Keiro had his face turned away. Attia always seemed silent, as if she had learned that keeping still and being overlooked kept her alive. Outside, the forest roared with the storm. He heard the cracking of its branches, the turmoil of its contempt surge from far distances, felt the strength of the wind batter the trees, shudder the iron trunk above him.

They had angered Incarceron. They had opened one of its forbidden doors and crossed some boundary. Perhaps it would trap them here forever, before they had barely begun.

At last, he couldn't wait any longer.

Cautiously, taking infinite pains to keep the rustle of the leaf-litter down, he tugged the Key from his pocket. It was cold, frosted with cold. His ringers left smeared imprints on it, and even the eagle inside was hard to see until he had rubbed condensation from its surface.

He held it tight. "Claudia" he breathed.

The Key was cold and dead.

No lights moved in it. He dared not speak louder.

But just then Gildas muttered, so he took the chance and curled up, bringing k closer.

"Can you hear me?" he said to it. "Are you there? Please, answer."

The storm raged. It whined in his teeth and nerves. He closed his eyes and felt despair, that he had imagined all of it, that the girl did not exist, that he was indeed born in some

Womb here.

And then, as if out of his own fear, came a voice, a soft remark. "Laughed? Are you sure that's what he said?"

Finn's eyes snapped open. A man's voice. Calm and considering.

He glanced around wildly, afraid the others had heard, and then a girl said, "... Of course

I'm sure. "Why should the old man laugh, Master, if Giles was dead?"

"Claudia." Finn whispered the name before he could stop himself.

Instantly Gildas turned; Keiro sat up. Cursing, Finn shoved the Key into his coat and rolled over to see Attia staring at him. He knew at once that she'd seen everything.

Keiro had his knife out. "Did you hear that? Someone outside." His blue eyes were alert.

"No." Finn swallowed. "It was me."

"Talking in your sleep?"

"He was talking to me," Attia said quietly.

For a moment Keiro looked at them both. Then he leaned back, but Finn knew he was not convinced. "Was he now?" his oathbrother said softly. "So who's Claudia?"

THEY CANTERED quickly up the lane, the deep green leaves of the oaks a tunnel over their heads. "And you believe Evian?"

"On this I do." She looked ahead at the mill rising at the foot of the hill. "The old man's reaction was all wrong, Master. He must have loved Giles."

"Grief affects people strangely, Claudia." Jared seemed worried. "Did you tell Evian you would find this Bartlett?"

"No. He—"

"Did you tell anyone? Alys?"

She snorted. "Tell Alys and it's around the servants' hall in minutes." That reminded her.

She slowed the breathless horse. "My father paid off the swordmaster. Or tried to. Has he said anything more to you?"

"No. Not yet."

They were silent while he leaned down and unlatched the gate, easing the horse back to drag it wide. On the other side the lane was rutted, lined by hedgerows, dog-roses twined among nettles and willow-herb, the white umbels of cow-parsley.

Jared sucked at a sting on his finger. Then he said, "That must be the place."

It was a low cottage half obscured by a great chestnut that grew beside it. As they rode closer Claudia scowled at its perfect Protocol, the thatch with holes in it, the damp walls, the gnarled trees of the orchard. "A hovel for the poor."

Jared smiled his sad smile. "I'm afraid so. In this Era only the rich know comfort."

They left the horses tied, cropping lush long grass from the verge. The gate was broken, hanging wide; Claudia saw how it had recently been forced, how the grass blades were dragged back under it, still wet with dew.

Jared stopped. "The doors open," he said.

She went to step past him, but he said, "A moment, Claudia." He took out the small scanner and let it hum. "Nothing.

No one here."

"Then we go in and wait for him. I've only got today." She strode up the cracked path;

Jared followed quickly.

Claudia pushed the door wider; it creaked and she thought something shuffled inside.

"Hello?" she said quietly.

Silence.

She put her head around the door.

The room was dark and smelled of smoke. A low window lit it, the shutter off and leaning against the wall. The fire was out in the hearth; as she came in she saw the blackened cooking pot on its chains, the spit, ashes drifting in the draft down the great chimney.

Two small benches lined the chimney corner; near the window stood a table and chair and a dresser with some battered pewter plates and a jug on it. She picked the jug up and sniffed the milk inside.

"Fresh."

There was a small doorway into the cow byre. Jared crossed to it and looked through, stooping under the lintel.

His back was to her, but she knew, from his sudden, intent stillness, something was wrong. "What?" she said.

He turned, and his face was so pale, she thought he was ill. He said, "I'm afraid we're too late."

She came over. He stayed, blocking her way. "I want to see," she muttered.

"Claudia..."

"Let me see, Master." She ducked under his arm.

The old man lay sprawled on the floor of the byre. It was quite obvious that his neck was broken. He lay on his back, arms flung out, one hand buried in the straw. His eyes were open.

The byre smelled of old dung. Flies buzzed endlessly and wasps came in and out through the open doorway; a small goat bleated outside.

Cold with awe and anger she said, "They killed him."

"We don't know that." Jared seemed to come to life all at once. He knelt by the old man, touched neck and wrist, ran the scanner over him.

"They killed him. He knew something about Giles, about the murder. They realized we were coming here!"

"Who could have realized?" He stood quickly, stepped back into the living room.

"Evian knew. My talk with him must have been bugged. Then there's Job. I asked him ..."

"Job's a child."

"He's scared of my father."

"Claudia, I'm scared of your father,"

She looked again at the small figure in the straw, letting her anger loose, clutching her arms around herself, "You can see the marks," she breathed.

Hand marks. Two bruises like the dark traces of thumbs, deep in the mottled flesh.

"Someone big. Very strong."

Jared jerked open the cupboard in the dresser and pulled out plates. "Certainly he didn't fall."

She turned.

He slammed the drawer, went to the chimney, and stared up. Then to her astonishment he climbed on one of the benches and reached into the darkness, groping blindly. Soot fell in showers.

"Master?"

"He lived at Court, Claudia. He must have been literate."

For a moment she didn't understand. Then she turned and gazed hurriedly around, found the bed, tipped the mattress up, tore open the lice-ridden straw.

Outside, a blackbird shrieked and flapped.

Claudia stared. "Are they coming back?"

"Maybe. Keep looking."

But as she moved her foot caught on a board that creaked, and when she knelt and pulled at it, it swung up on a pivot with the ease of constant use.

"Jared!"

It was the old man's store of treasures. A battered purse with some copper coins, a broken necklace with most of the stones pried out, two quills, a fold of parchment, and, carefully hidden right at the bottom, a blue velvet drawstring bag, small as her palm.

Jared took the parchment and riffled through it. "Looks like some sort of testament. I knew he would have written it down! If he'd been taught by Sapienti, it's only ..." He glanced over. She had opened the blue bag. Out of it she slid a small oval of gold, its back engraved with the crowned eagle. She turned it over.

A boy's face looked up at them, his smile shy and direct, his eyes brown.

Claudia smiled back at him, bitter. She looked up at her tutor. "It must be worth a fortune, but he never sold it. He must have loved him very much."

Gently he said, "Are you sure ...?"

"Oh yes, I'm sure. It's Giles."