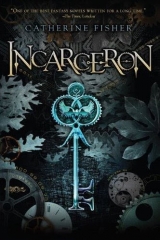

Текст книги "Incarceron"

Автор книги: Kathryn Fisher

Жанр:

Классическое фэнтези

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 19 страниц)

Catherine Fisher

INCARCERON

To Sheenagh Pugh brilliant poet, wise webmistress.

CRYSTAL EAGLE, DARK SWAN

1

Who can chart the vastness of Incarceron?

Its halls and viaducts, its chasms?

Only the man who has known freedom

Can define his prison.

-Songs of Sapphique

Finn had been flung on his face and chained to the stone slabs of the transitway. His arms, spread wide, were weighted with links so heavy, he could barely drag his wrists off the ground. His ankles were tangled in a slithering mass of metal, bolted through a ring in the pavement. He couldn't raise his chest to get enough air. He lay exhausted, the stone icy against his cheek. But the Civicry were coming at last.

He felt them before he heard them; vibrations in the ground, starting tiny and growing until they shivered in his teeth and nerves. Then noises in the darkness, the rumble of migration trucks, the slow hollow clang of wheel rims. Dragging his head around, he shook dirty hair out of his eyes and saw how the parallel grooves in the floor arrowed straight under his body. He was chained directly across the tracks.

Sweat slicked his forehead. Gripping the frosted links with one glove he hauled his chest up and gasped in a breath. The air was acrid and smelled of oil.

It was no use yelling yet. They were too far off and wouldn't hear him over the clamor of the wheels until they were well into the vast hall. He would have to time it exactly. Too late, and the trucks couldn't be stopped, and he would be crushed. Desperately, he tried to avoid the other thought. That they might see him and hear him and not even care.

Lights.

Small, bobbing, handheld lights. Concentrating, he counted nine, eleven, twelve; then counted them again to have a number that was firm, that would stand against the nausea choking his throat.

Nuzzling his face against the torn sleeve for some comfort he thought of Keiro, his grin, the last mocking little slap as he'd checked the lock and stepped back into the dark. He whispered the name, a bitter whisper: "Keiro."

Vast halls and invisible galleries swallowed it. Fog hung in the metallic air. The trucks clanged and groaned.

He could see people now, trudging. They emerged from the darkness so muffled against the cold, it was hard to tell if they were children or old, bent women. Probably children—the aged, if they kept any, would ride on the trams, with the goods. A black-and-white ragged flag draped the leading truck; he could see its design, a heraldic bird with a silver bolt in its beak.

"Stop!" he called. "Look! Down here!"

The grinding of machinery shuddered the floor. It whined in his bones. He clenched his hands as the sheer weight and impetus of the trucks came home to him, the smell of sweat from the massed ranks of men pushing them, the rattle and slither of piled goods.

He waited, forcing his terror down, second by second testing his nerve against death, not breathing, not letting himself break, because he was Finn the Starseer, he could do this.

Until from nowhere a sweating panic erupted and he heaved himself up and screamed, "Did you hear me! Stop! Stop?

They came on.

The noise was unbearable. Now he howled and kicked and struggled, because the terrible momentum of the loaded trucks would slide relentlessly, loom over him, darken him, crush his bones and body in slow inevitable agony.

Until he remembered the flashlight.

It was tiny but he still had it. Keiro had made sure of that. Dragging the weight of the chain, he rolled and wriggled his hand inside his coat, wrist muscles twisting in spasm.

His fingers slid on the slim cold tube.

Vibrations shuddered through his body. He jerked the flashlight out and dropped it and it rolled, just out of reach. He cursed, squirmed, pressed it on with his chin.

Light beamed.

He was gasping with relief, but the trucks still came on. Surely the Civicry could see him.

They must be able to see him!

The flashlight was a star in the immense rumbling darkness of the hall, and in that moment, through all its stairs and galleries and thousands of labyrinthine chambers he knew Incarceron had sensed his peril, and the crash of the trucks was its harsh amusement, that the Prison watched him and would not interfere.

"I know you can see me!" he screamed.

The wheels were man-high. They shrieked in the grooves; sparks fountained across the paving. A child called, a high shout, and Finn groaned and huddled tight, knowing none of it had worked, knowing it was finished, and then the wail of the brakes hit him, the screech in his bones and fingers.

The wheels loomed. They were high above. They were over him.

They were still.

He couldn't move. His body was a limp rag of terror. The flashlight illuminated nothing but a fist-thick rivet in an oily flange.

Then, beyond it, a voice demanded, "What's your name, Prisoner?"

They were gathered in the darkness. He managed to lift his head and saw shapes, hooded.

"Finn. My name's Finn." His voice was a whisper; he had to swallow. "I didn't think you were going to stop ..."

A grunt. Someone else said, "Looks like Scum to me."

"No! Please! Please get me up." They were silent and no one moved, so he took a breath and said tightly, "The Scum raided our Wing. They killed my father and they left me like this for anyone who passed." He tried to ease the agony in his chest, clenching his fingers on the rusty chain. "Please. I'm begging you."

Someone came close. The toe of a boot halted next to his eye; dirty, with one patched hole.

"What sort of Scum?"

"The Comitatus. Their leader called himself Jormanric the Winglord."

The man spat, close to Finn's ear. "That one! He's a crazed thug."

Why was nothing happening? Finn squirmed, desperate. "Please! They may come back!"

"I say we ride over him. Why interfere?"

"Because we're Civicry, not Scum." To Finn's surprise, a woman. He heard the rustle of her silk clothes under the coarse travelcoat. She knelt and he saw her gloved hand tug at the chains. His wrist was bleeding; rust made powdery loops on his grimy skin.

The man said uneasily, "Maestra, listen ..."

"Get bolt-cutters, Sim. Now."

Her face was close to Finn's. "Don't worry, Finn. I won't leave you here."

Painfully, he looked up, saw a woman of about twenty, her hair red, her eyes dark. For a moment he smelled her; a drift of soap and soft wool, a heart-stabbing scent that broke into his memory, into that black locked box inside him. A room. A room with an applewood fire. A cake on a china plate.

The shock must have shown on his face; from the shadow of her hood she looked at him thoughtfully. "You'll be safe with us."

Finn stared back. He couldn't breathe.

A nursery. The walls stone. The hangings rich and red.

A man came hastily and slid the cutter under the chain. "Watch your eyes," he growled.

Finn dropped his head on his sleeve, sensing people crowding around. For a moment he thought one of the fits he dreaded was coming over him; he closed his eyes and felt the familiar dizzying heat sweep his body. He fought it, swallowing saliva, gripping the chains as the massive cutters sheared them open. The memory was fading; the room and the fire, the cake with tiny silver balls on a gold-bordered plate. Even as he tried to keep it, it was gone, and the icy darkness of Incarceron was back, the sour metallic stench of oily wheels.

Links slid and rattled. He heaved himself upright in relief, dragging in deep breaths. The woman took his wrist and turned it over. "This will need dressing."

He froze. He couldn't move. Her fingers were cool and clean, and she had touched him on his skin, between the torn sleeve and the glove, and she was looking at the tiny tattoo of the crowned bird.

She frowned. "That's not a Civicry mark. It looks like ..."

"What?" He was alert at once. "Like what?"

A rumble miles off in the hall. The chains at his feet slithered. Bending over them the man with the cutters hesitated. "That's odd. This bolt. It's loose ..."

The Maestra stared at the bird. "Like the crystal."

A shout, behind them.

"What crystal?" Finn said.

"A strange object. We found it."

"And the bird is the same? You're sure?"

"Yes." Distracted, she turned and looked at the bolt. "You weren't really—"

He had to know about this. He had to keep her alive. He grabbed her and pulled her to the floor. "Get down," he whispered. And then, angrily, "Don't you understand? It's all a trap!'

For a moment her eyes stared into his and he saw their surprise fractured into horror. She jerked out of his grip; with one twist was up and screaming, "Run! Everyone run!" But the grids in the floor were crashing open; arms came out, bodies were heaved up, weapons slammed down on the stone.

Finn moved. He flung the man with the cutters back, kicked the false bolt off, and wriggled out of the chains. Keiro was yelling at him; a cutlass flashed past his head and he threw himself down, rolled, and looked up.

The hall was black with smoke. The Civicry were screaming, racing for the shelter of the vast pillars, but already the

Scum were on the wagons, firing indiscriminately, red flashes from the clumsy firelocks turning the hall acrid.

He couldn't see her. She might be dead, she might be running. Someone shoved him and thrust a weapon into his hand; he thought it was Lis, but the Scum all wore their dark helms and he couldn't tell.

Then he saw the woman. She was pushing children under the first wagon; a small boy was sobbing and she grabbed him and flung him in front of her. But gas was hissing from the small spheres that fell and cracked like eggs, its sting making Finn's eyes water. He pulled out his helm and dragged it on, the soaked pads over nose and mouth magnifying his breathing. Through its eye grid the hall was red, the figures clear.

She had a weapon and was firing with it.

"Finn!"

It was Keiro, but Finn ignored the shout. He ran for the first truck, dived under it, and grabbed the Maestra's arm; as she turned he knocked the weapon aside and she screamed in anger and went for his face with her nailed gloves, the spines clawing at his helm. As he dragged her out, the children kicked and struggled with him, and a cascade of foodstuffs was tossed down around them, caught, stowed, slid efficiently into chutes down the grids.

An alarm howled.

Incarceron stirred.

Smooth panels slid aside in the walls; with a click, spotlights of brilliant light stabbed down from the invisible roof, roaming back and forth over the distant floor, picking out the Scum as they scattered like rats, their stark shadows enormous. "Evacuate!" Keiro yelled.

Finn pushed the woman on. Next to them a running figure was drilled with light and evaporated soundlessly, caught in mid-panic. Children wailed.

The woman turned, breathless with shock, staring back at the remnants of her people.

Then Finn dragged her to the chute.

Through the mask his eyes met hers.

"Down there," he gasped. "Or you'll die."

For a moment he almost thought she wouldn't.

Then she spat at him, snatched herself out of his hands, and jumped into the chute.

A spark of white fire scorched over the stones; instantly, Finn jumped after her.

The chute was of white silk, strong and taut. He slid down it in a breathlessness that tipped him out at the other end onto a pile of stolen furs and bruising metal components.

Already hauled to one side, a weapon at her head, the Maestra watched in scorn.

Finn picked himself up painfully. All around, the Scum were sliding into the tunnel, encumbered with plunder, some hobbling, some barely conscious. Last of all, landing lightly on his feet, came Keiro.

The grids slammed shut.

The chutes fell away.

Dim shapes gasped and coughed and tore off masks.

Keiro removed his slowly, revealing his handsome face smeared with dust. Finn swung on him in fury. "What happened? I was panicked out there! What rook you so long?"

Keiro smiled. "Calm down. Aklo couldn't get the gas to work. You kept them talking well enough." He looked at the woman. "Why bother with her?"

Finn shrugged, still simmering. "She's a hostage."

Keiro raised an eyebrow. "Too much trouble." He jerked his head at the man holding the weapon; the man snicked back the trigger. The Maestra's face was white.

"So I don't get anything extra for risking my life up there." Finn's voice was steady . He didn't move, but Keiro looked over at him. For a moment they stared at each other. Then his oath-brother said coolly , "If she's what you want."

"She's what I want."

Keiro glanced at the woman again, and shrugged. "No accounting for taste." He nodded, and the weapon was lowered. Then he slapped Finn on the shoulder, so that a cloud of dust rose from his clothes. "Well done, brother," he said.

2

We will choose an Era from the past and re-create it.

We will make a world free from the anxiety of change!

It will be Paradise!

-King Endor's Decree

The oak tree looked genuine, but it had been genetically aged. The boughs were so huge that climbing them was easy; as she hitched up her skirt and scrambled higher, twigs snapped and green lichen dusted her hands. "Claudia! It's four o'clock!"

Alys's screech came from somewhere in the rose garden. Claudia ignored it, parted the leaves, and looked out.

From this height she could see the whole estate; the kitchen garden, glasshouses, and orangery, the gnarled apple trees in the orchard, the barns where the dances were held in winter. She could see the long green lawns that sloped down to the lake and the beechwoods hiding the lane to Hithercross. Farther to the west the chimneys of Altan

Farm smoked, and the old church steeple crowned Harmer Hill, its weathercock glinting in the sun. Beyond, for miles and miles, the countryside of the Wardenry lay open before her, meadows and villages and lanes, a blue-green patchwork smudged with mist above the rivers.

She sighed and leaned back against the trunk. It looked so peaceful. So perfect in its deception. She would hate to leave it.

"Claudia! Hurry!"

The call was fainter. Her nurse must have run back toward the house, because a scatter of pigeons flapped up, as if someone was climbing the steps by their cote. As Claudia listened, the clock on the stables began to strike the hour, slow chimes sliding out into the hot afternoon.

The countryside shimmered.

Far off, on the high road, she saw the coach.

Her lips tightened. He was early.

It was a black carriage, and even from here she could make out the cloud of dust its wheels raised from the road. Four black horses pulled it, and outriders flanked it; she counted eight of them and snorted a silent laugh. The Warden of Incarceron was traveling in style. The blazon of his office was painted on the coach doors, and a long pennant streamed out in the wind. On the box a driver in black and gold livery wrestled with the reins; she heard the rattle of a whip clear on the breeze.

Above her a bird cheeped and fluttered from branch to branch; she kept very still and it perched in the leaf cover near her face. Then it sang; a brief creamy warble. Some sort of finch, perhaps.

The coach had reached the village. She saw the blacksmith come to his door, a few children run out of a barn. As the riders thundered through, dogs barked and the horses bunched together between the narrow overhanging houses.

Claudia reached into her pocket and took out the visor. It was non-Era and illegal, but she didn't care. Slipping it over her eyes she felt the dizzying second as the lens adjusted to her optic nerve; then the scene magnified and she saw the features of the men clearly: her fathers steward, Garrh, on the roan horse; the dark secretary, Lucas Medlicote; the menat-arms with their pied coats.

The visor was so efficient she could almost lip-read as the coachman swore; then the posts of the bridge flashed past and she realized they had reached the river and the lodge. Mistress Simmy was running out to open the gates with a dishcloth still in her hands, hens panicking before her.

Claudia frowned. She took off the visor and the movement made the bird fly; the world slid back and the coach was small. Alys wailed, "Claudia! They're here! Will you come and get dressed!"

For a moment she thought she wouldn't. She toyed with the idea of letting the carriage rumble in and climbing down from the tree and strolling over, opening the door, and standing there in front of him, with her hair in a tangle and the old green dress with the tear in its hem. Her father's displeasure would be stiff, but he wouldn't say anything. If she turned up naked he probably wouldn't say anything. Just "Claudia. My dear." And the cold kiss printed under her ear.

She swung over the bough and climbed down, wondering if there would be a present.

There usually was. Expensive and pretty and chosen for him by one of the ladies of the

Court. Last time it had been a crystal bird in a gold cage that trilled a shrill whistle. Even though the whole estate was full of birds, mostly real ones, which flew and squabbled and chirruped outside the casements.

Jumping off, she ran across the lawn to the wide stone steps; as she descended them, the manor house rose in front of her, its warm stone glowing in the heat, the wisteria hanging purple over its turrets and crooked corners, the deep moat dark under three elegant swans. On the roof doves had settled, cooing and strutting; some of them flew to the corner turrets and tucked themselves into loopholes and arrow slits, on heaps of straw that had taken generations to gather. Or so you'd think.

A casement unclicked; Alys's hot face gasped, "Where have you been! Can't you hear them?"

"I can hear them. Stop panicking."

As she raced up the steps the carriage was rumbling over the timbers of the bridge; she saw its blackness flicker through the balustrade; then the cool dimness of the house was around her, with its scents of rosemary and lavender. A serving girl came out of the kitchens, dropped a hasty curtsy, and disappeared. Claudia hurtled up the stairs.

In her room Alys was dragging clothes out of the closet. A silken petticoat, the blue and gold dress over it, the bodice quickly laced. Claudia stood there and let herself be strapped and fastened into it, the hated cage she was kept in. Over her nurse's shoulder she saw the crystal bird in the tiny prison, its beak agape, and scowled at it.

"Keep still."

"I am still!"

"I suppose you were with Jared."

Claudia shrugged. Gloom was settling over her. She couldn't be bothered to explain.

The bodice was too tight, but she was used to it. Her hair was fiercely brushed and the pearl net pinned into it; it crackled with static on the velvet of her shoulders. Breathless, the old woman stepped back. "You'd look better if you weren't scowling.

"I'll scowl if I want to." Claudia turned to the door, feeling the whole dress sway. "One day

I'll howl and scream and yell in his face."

"I don't think so." Alys stuffed the old green dress into the chest. She glanced in the mirror and tucked the gray hairs back under her wimple, took a laser skinwand out, unscrewed it, and skillfully eliminated a wrinkle under her eye.

"If I'm going to be Queen, who's to stop me?"

"He is." Her nurse's retort followed her through the door. "And you're just as terrified of him as everyone else."

It was true. Walking sedately down the stairs, she knew it had always been true. Her life was fractured into two; the time when her father was here, and the time he was away. She lived two lives, and so did the servants, the whole house, the estate, the world.

As she crossed the wooden floor between the breathless, sweating double row of gardeners and dairywomen, lackeys and link-men, toward the coach that had rumbled to a halt in the cobbled courtyard, she wondered if he had any idea of that. Probably. He didn't miss much.

On the steps she waited. Horses snorted; the clatter of their hooves was huge in the enclosed space. Someone shouted, old Ralph hurried forward; two powdered men in livery leaped from the back of the coach, opened the door, snapped down the steps.

For a moment the doorway was dark.

Then his hand grasped the coachwork; his dark hat came out, his shoulders, a boot, black knee breeches.

John Arlex, Warden of Incarceron, stood upright and flicked dust off himself with his gloves.

He was a tall, straight man, his beard carefully trimmed, his frockcoat and waistcoat of the finest brocade. It had been six months since she had seen him, but he looked exactly the same. No one of his status need show signs of age, but he didn't even seem to use a skinwand. He looked at her and smiled graciously; his dark hair, tied in the black ribbon, was elegantly silvered.

"Claudia. How well you look, my dear."

She stepped forward and dropped a low curtsy, then his hand raised her and she felt the cold kiss. His fingers were always cool and slightly clammy, unpleasant to touch; as if he was aware of it, he usually wore gloves, even in warm weather. She wondered if he thought she had changed. "As do you, Father," she muttered.

For a moment he remained looking at her, the calm gray gaze hard and clear as ever.

Then he turned.

"Allow me to present our guest. The Queen's Chancellor. Lord Evian."

The carriage rocked. An extremely fat man unfurled from it, and with him a wave of scent that seemed to roll almost visibly up the steps. Behind her Claudia sensed the servants' collective interest. She felt only dismay.

The Chancellor wore a blue silk suit with an elaborate ruffle at the neck, so high she wondered how he could breathe. He was certainly red in the face, but his bow was assured and his smile carefully pleasant. "My lady Claudia. The last time I saw you, you were no more than a baby in arms. How delightful to see you again."

She hadn't expected a visitor. The main guestroom was heaped with the half-sewn train of her wedding dress all over its unmade bed. She'd have to use delaying tactics.

"The honor is ours," she said. "Perhaps you'd like to come into the parlor. We have cider and newly baked cakes as refreshment after your journey." Well, she hoped they did.

Turning, she saw three of the servants had gone and the gaps in the line had closed swiftly behind them. Her father gave her a cool look, then walked up the steps, nodding graciously along the row of faces that curtsied and bobbed and dropped their eyes before him.

Smiling tightly, Claudia thought fast. Evian was the Queen's man. The witch must have sent him to look the bride over. Well, that was fine by her. She'd been preparing for this for years.

At the door her father stopped. "No Jared?" he said lightly.

"I hope he's well?"

"I think he's working on a very delicate process. He probably hasn't even noticed you've arrived." It was true, but it sounded like an excuse. Annoyed at his wintry smile she led them, her skirts sweeping the bare boards, into the parlor. It was a wood-paneled room dark with a great mahogany sideboard, carved chairs, and a trestle table. She was relieved to see cider jugs and a platter of the cook's honeycakes among a scatter of lavender and rosemary.

Lord Evian sniffed the sweet scents. "Wonderful," he said. "Even the Court couldn't match the authenticity."

Probably because most of the Courts backdrop was computer-generated, she thought sweetly, and said, "At the Wardenry, my lord, we pride ourselves that everything is in Era.

The house is truly old. It was restored fully after the Years of Rage."

Her father was silent. He sat in the carved chair at the head of the table and watched gravely as Ralph poured the cider into silver goblets. The old man's hand shook as he lifted the tray. "Welcome home, sir."

"Good to see you, Ralph. A little more gray about the eyebrows, I think. And your wig fuller, with more powder."

Ralph bowed. "I'll have it seen to, Warden, immediately."

The Warden's eyes surveyed the room. She knew he wouldn't miss the single pane of Plastiglas in the corner of the casement, or the prefabricated spiderwebs on the pargeted ceiling. So she said hastily, "How is Her Gracious Majesty, my lord?"

"The Queen's in excellent health." Evian spoke through a mouthful of cake. "She's very busy with arrangements for your wedding. It will be a great spectacle."

Claudia frowned. "But surely ..."

He waved a plump hand. "Of course your father hasn't had time to tell you about the change of plans."

Something inside her went cold. "Change of plans?"

"Nothing terrible, child. Nothing to concern yourself about. An alteration of dates, that's all.

Because of the Earl's return horn the Academy."

She cleared her face and tried to allow none of her anxiety to show itself. But her lips must have tightened or her knuckles gone white, because her father stood smoothly and said, "Show His Lordship to his room, Ralph."

The old retainer bowed, went to the door, and creaked it open. Evian struggled up, a shower of crumbs cascading from his suit. As they hit the floor, they evaporated with minute flashes.

Claudia swore silently. Something else to get seen to.

They listened to the heavy footsteps up the creaking stairs, to Ralph's respectful murmurs and the rumble of the fat man's hearty enjoyment of the staircase, the paintings, the urns from China, the damask hangings. When his voice had finally faded in the sunlit distances of the house Claudia looked at her father. Then she said, "You've brought the wedding forward."

He raised an eyebrow. "Next year, this year, what's the difference? You knew it would come." "I'm not ready ..."

"You've been ready for a long time."

He took a step toward her, the silver cube on his watch chain catching the light. She stepped back. If he should drop the formal stiffness of the Era, it would be unbearable; the threat of his unveiled personality turned her cold. But he kept the smooth courtesy. "Let me explain. Last month a message came from the Sapienti. They've had enough of your fiancé. They've ... asked him to leave the Academy."

She frowned. "For what?"

"The usual vices. Drink, drugs, violence, getting serving girls pregnant. Sins of stupid young men throughout the centuries. He has no interest in education. Why should he?

He's the Earl of Steen and when he is eighteen he will be King."

He walked to the paneled wall and looked up at the portrait there. A freckled cheekyfaced boy of seven looked down at them. He was dressed in a ruffled brown silk suit, and leaning against a tree.

"Caspar, Earl of Steen. Crown Prince of the Realm. Fine titles. His face hasn't changed, has it? He was merely impudent then. Now he's feckless, brutal, and thinks he is beyond control." He looked at her. "A challenge, your future husband."

She shrugged, making the dress rustle. "I can deal with him."

"Of course you can. I've made sure of that." He came over to her and stood before her, and his gray gaze appraised her. She stared straight back.

"I created you for this marriage, Claudia. Gave you taste, intelligence, ruthlessness. Your education has been more rigorous than anyone's in the Realm. Languages, music, swordplay, riding, every talent you even hinted at possessing I have nurtured. Expense is nothing to the Warden of Incarceron. You are an heiress of great estates. I've bred you as a queen and Queen you will be. In every marriage, one leads, one follows. Though this is merely a dynastic arrangement, it will be so here."

She looked up at the portrait. "I can handle Caspar. But his mother ..."

"Leave the Queen to me. She and I understand each other." He took her hand, holding her ring finger lightly between two of his; tense, she held herself still.

"It will be easy," he breathed.

In the stillness of the warm room a wood pigeon cooed outside the casement.

Carefully, she took her hand from his and drew herself up. "So, when?"

"Next week."

"Next week!"

"The Queen has already begun preparations. In two days we set off for Court. Make sure you're ready."

Claudia said nothing. She felt empty, and stunned.

John Arlex turned toward the door. "You've done well here. The Era is impeccable, except for that window. Get it changed."

Without moving she said quietly, "How was your time at Court?"

"Wearisome."

"And your work? How is Incarceron?"

For a fraction of a second he paused. Her heart thudded. Then he turned and his voice was cold and curious. "The Prison is in excellent order. Why do you ask?"

"No reason." She tried to smile, wanting to know how he monitored the Prison, where it was, because all her spies had told her he never left the Court. But the mysteries of Incarceron were the least of her worries now.

"Ah yes. I nearly forgot." He crossed to a leather bag on the table and tugged it open. "I bring a gift from your future mother-in-law." He pulled it out and set it down.

They both looked at it.

A sandalwood box, tied with ribbon.

Reluctant, Claudia reached out for the tiny bow, but he said, "Wait," took out a small scanning wand, and moved it over the box. Images flashed down its stem. "Harmless."

He folded the wand. "Open it."

She lifted the lid. Inside, in a frame of gold and pearls, was an enameled miniature of a black swan on a lake, the emblem of her house. She took it out and smiled, pleased despite herself by the delicate blue of the water, the bird's long elegant neck. It's pretty.

"Yes, but watch."

The swan was moving. It seemed to glide, peacefully at first; then it reared up, flapping its great wings, and she saw how an arrow came slowly out of the trees and pierced its breast. It opened its golden beak and sang, an eerie, terrible music. Then it sank under the water and vanished.

Her father's smile was acid. "How very charming," he said.