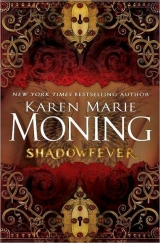

Текст книги "Shadowfever"

Автор книги: Karen Marie Moning

Соавторы: Karen Marie Moning,Karen Marie Moning

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 13 (всего у книги 37 страниц)

“It’s said the king was horrified when he realized that his act of atonement had resulted in the birth of his most powerful abomination yet. He chased it from one world to the next, for eons, determined to destroy it. When he finally caught up with it, their battle lasted centuries and reduced dozens of worlds to ruins. But it was too late. The Sinsar Dubh had become fully sentient, a dark force of its own. When the king first created the Sinsar Dubh, he was greater, and the Book was lesser. It was a repository for the king’s evil, but without drive and intent. Yet while it roamed, it evolved, until it became all the king was, and more. The creation—abandoned by its creator—learned to hate. The Sinsar Dubh began to pursue the king.” He paused and gave me one of his wolf smiles. “So what else might the dark king have created? Perhaps an entire caste that could track his greatest enemy, contain it, and keep it from destroying him? Are you going to tell me you never once considered that?”

I stared. We were the good guys. Human to the core.

“Sidhe-seers: watchdogs for the U.K.,” he mocked.

I was chilled by his words. It had been bad enough to discover I was adopted and the parents who’d raised me weren’t my biological parents. Now what was he implying? That I’d had no parents?

“That’s the biggest pile of BS I’ve ever heard.” First Darroc had suggested I was a stone. Now Barrons was proposing that the sidhe-seers were a secret caste of Unseelie.

“If it walks like a duck and quacks like a duck.”

“I am not a duck.”

“Why does it offend you so much? Power is power.”

“The Unseelie King didn’t make me!”

“The idea frightens you. Fear is more than a wasted emotion. It’s the penultimate set of blinders. If you can’t face the truth of your reality, you can’t be a part of it, can’t control it. You may as well throw in the towel and yield to the whims of anyone with a stronger will. Do you like being helpless? Is that what you get off on? Is that why the moment I was gone you turned to the bastard that had you raped?”

“So, what are you and your men?” I countered coldly. “Another of the Unseelie King’s secret castes? Is that what you are, Barrons? Is that why you know so much about them?”

“None of your fucking business.”

He turned away and resumed his search.

I was trembling, and there was a sour taste in my mouth. I pushed the papers away, got up, and walked to the balcony, where I stood staring out at the night.

Barrons had shaken me deeply with his suggestion that the sidhe-seers were a caste of Unseelie. I had to admit that Darroc’s notes could certainly be construed that way.

And just the other night, I’d stood between two Fae armies, thinking how glad I was to be like the Unseelie, strengthened by pain, less frivolous and breakable.

Then there was that dark glassy lake in my head, that had so many inexplicable “gifts” to offer, like runes that an ex-Fae had recognized, that had given him pause, runes that the Unseelie princes had disliked intensely.

I shivered. I had a new question to be obsessed with besides what was Jericho Barrons?

What was I?

18

When we left, I snatched a Dani Daily from the lamppost outside the building, slid into the passenger’s seat of the Viper, and began to read it. Her birthday was coming up. I smiled faintly. Figured she’d tell the whole world. She’d make it a national holiday if she could.

I wasn’t surprised to learn she’d been in the street last night and had seen the Hunter kill Darroc. Dani didn’t take orders from anyone, not even me. Had she been there to try to kill Darroc herself? I wouldn’t put it past her.

As I fastened my seat belt, I wondered whether she hadn’t stuck around long enough to see that the Hunter had been possessed by the Sinsar Dubh, or if she’d decided to omit that bit of news. If she had stuck around, what did she make of the beast that blasted into me and carried me off? Probably figured it was some other kind of Unseelie she hadn’t seen before.

Although I was shocked to realize so much time had passed while I was in the Silvers and it was the middle of February, I should have known today was Valentine’s Day.

I glanced sourly over at Barrons.

I’d never had a happy one. They’d been various shades of sucky since kindergarten, when Chip Johnson ate too many iced cookies and threw up all over my new dress. I’d been drinking fruit punch, and when his puke hit me, I had an involuntary sympathetic response and spewed punch everywhere. It had set off a chain reaction of five-year-olds vomiting that I still couldn’t think about without getting queasy.

Even back in second and third grade, Valentine’s Day had been a stressful experience for me. I’d wake up dreading school. Mom always got Alina and me cards for everyone in our class, but a lot of moms weren’t as sensitive. I’d sit at my desk and hold my breath, praying someone besides Tubby Thompson or Blinky Brewer would remember me.

Then, in middle school, we had the Sadie Hawkins dance, where the girls had to ask the guys to go, putting on even more pressure. Adding insult to injury on what was supposed to be the most romantic day of the year, I was forced to risk rejection by asking out the guy of my dreams and praying that, by the time I got my nerve up, there’d be someone left besides Tubby and Blinky. In eighth grade, I waited too long and nobody popular was left, so I’d blow-dried my forehead on the high-heat setting, spritzed my sheets with water, and faked the flu that morning. Mom made me go anyway. The scorch mark on my forehead gave me away. I’d hastily cut bangs to try to cover it and had ended up at the dance dateless, miserable, with a painful burn and a bad haircut.

High school brought along a whole new set of problems. I shook my head, in no mood to relive teenage horrors. Bright side was, this Valentine’s Day could have been a whole lot worse. At least I’d get to sleep tonight with the comforting knowledge that Barrons was alive.

“Where to now?” I asked.

He stared straight ahead. The rattlesnake moved in his chest.

We pulled up at 939 Rêvemal Street, in front of the demolished entrance to Chester’s, the club that had once been Dublin’s number-one hotspot for the jaded rich and beautiful bored, until it was destroyed on Halloween. I stared at him disbelievingly.

He parked and turned off the engine.

“I’m not going in Chester’s. They want me dead in there.”

“And if they smell fear on you, they’ll try to kill you.” He opened the door and got out.

“Your point?”

“If I were you, I’d try to smell like something else.”

“Why do I have to go in?” I groused. “Can’t you visit your buddies by yourself?”

“Do you want to see your parents or not?”

I leapt out, slammed the door, and ran after him, skirting rubble. I had no idea why he was offering—certainly not because he was trying to be nice—but I wasn’t about to miss the opportunity. As unpredictable as my life was, I wasn’t going to miss a single chance to spend time with the people I loved.

As if he’d read my thoughts, he tossed over his shoulder, “I said see them. Not visit with them.”

I hated the thought of my parents being held in the belly of the seedy Unseelie hangout, but I had to concede that underground, in the middle of Barrons’ men, was probably the safest place for them. They couldn’t go back to Ashford. The Unseelie Princes knew where we lived.

The only other possibilities were the abbey, the bookstore, or with V’lane. Not only were there Shades in the abbey still, the Sinsar Dubh had paid a deadly visit, and I didn’t trust Rowena with a butter knife. I certainly didn’t want them hanging around me, seeing what a mess I’d become. And V’lane—with his dim understanding of humans—might decide to tuck them away on a beach with an illusion of Alina, which my dad could handle, but it would definitely push my mom over the edge. We might never get her out of there.

Chester’s it was.

The club had once been the most popular place in the city, accessible by invitation only, with marble pillars that framed an ornate entrance into the three-story club, but lavish French-style gas lamps had been ripped from the concrete and used as battering rams against the façade. Fallen roof supports had crushed a world-renowned hand-carved bar and shattered elegant stained-glass windows. The club sign dangled in pieces above the entrance, chunks of concrete blocked the door, and the building was heavily covered with graffiti.

The new entrance to the club was around back, secreted beneath an inconspicuous, battered metal door in the ground, close to the crumbling foundation. If you didn’t know about the club, you wouldn’t give a second thought to what appeared to be a forgotten cellar door. The dance floors were so far underground and so well soundproofed that, unless you had Dani’s superhearing, you’d never know there was a party going on.

“I can’t be part of an Unseelie caste,” I told him as he opened the door. “I can touch the Seelie spear.”

“Some say the Unseelie King created the sidhe-seers with his imperfect Song. Others say he had sex with human women to found the bloodlines. Perhaps your blood is diluted enough that it poses no such problem.”

Typical Barrons. He had an answer for all the things I didn’t want to know but none for the things I did.

After descending a ladder, pushing open another door, and going down a second ladder, we arrived at the real entrance to the club, an industrial foyer with tall double doors.

Since I’d last been here, someone had hired a decorator and replaced the tall wood doors with new ones that were black and glossy, the height of urban chic, so highly polished that I could see the couple who’d followed us down reflected in them. She was dressed like me in a long slim skirt, high-heeled boots, and a fur-trimmed coat. He stood near, his body angled in on her, like a walking shield.

I jerked. No couple had followed us down. I hadn’t recognized myself. It wasn’t that my hair was blond again—the black doors reflected only shape and movement, not color—it was that I looked like someone else. I stood differently. Gone was the last vestige of baby softness I’d brought with me to Dublin last August. I wondered what Mom and Dad would think of me. I hoped they could see past the changes to the Mac I still was somewhere beneath it all. I was excited and nervous to see them.

He pushed the doors open. “Stay close.”

The club hit me like a blast of overblown sensuality, cool in chrome and glass, black and white, the height of industrial muscle dressed in Manhattan posh. The décor promised uninhibited eroticism, pleasure for pleasure’s sake, sex worth dying for. The enormous interior was terraced with dance floors, each served by their own bars on a dozen different sublevels. The mini-clubs within the club had their own themes, some elegant on polished floors, others heavy on tattoos and urban decay. The bartenders and servers reflected the theme of their sub-club, some in topless tuxes, others in leather and chains. On one terrace, the extremely young servers were dressed like uniformed schoolchildren. On another—I turned sharply away. Not looking, not thinking about that one. I hoped Barrons was keeping my parents somewhere far from all this debauchery.

Although I’d mentally prepared myself to see humans and Unseelie mingling, flirting, and pairing off, I’m never ready for it. Chester’s is anathema to everything I am.

Fae and human were not meant to mix. The Fae are immortal predators, with no regard for human life, and those humans foolish enough to think for one moment that their tiny inconsequential lives matter to the Fae … well, Ryodan says those humans deserve to die, and when I see them in a place like Chester’s, I have to agree. You can’t save people from themselves. You can only try to wake them up.

The static of so many Unseelie crowded into one place was deafening. Grimacing, I turned off my sidhe-seer volume.

Music spilled from one level to the next, overlapping. Sinatra dueled with Manson; Zombie flipped off Pavarotti. The message was clear: If you want it, we’ve got it, and if we don’t, we’ll create it for you.

Still, there was one theme the whole place shared: Chester’s had been decorated for Valentine’s Day.

“This is just wrong,” I muttered.

Thousands of pink and red balloons dangling silken cords drifted through the club, emblazoned with messages that ranged from sweet to cheeky to horrifying.

At the entrance to every mini-club was a huge golden statue of Cupid holding a bow that sported dozens of long golden arrows.

The human contingent of Chester’s clientele was chasing the balloons from one level to the next, climbing stairs, perching on stools, yanking them lower, and popping them with their arrows, which I didn’t get at all until I watched a folded bit of paper explode from one, and then a dozen women piled up in a heap of fighting, clawing wildcats, determined to get whatever the prize was.

When one woman finally broke free from the mess, clutching her treasure, three others ganged up on her, stabbed her with their arrows, and took it away. Then they turned on one another with shocking brutality. A man rushed in, snatched the wad of paper, and ran.

I looked around for Barrons, but we’d gotten separated in the crowd. I shoved dangling silk cords from my face.

“Don’t you want one?” a redhead chirped, as she snatched the cord of one I’d just pushed away.

“What’s in them?” I said warily.

“Invitations, silly! If you’re lucky! But there aren’t many! If you get one, they’ll let you in to the private rooms to dine upon the sanctified flesh of the immortal Fae for the whole night!” she twittered rapturously. “Others have gifts!”

“Like what?”

She stabbed at the balloon with a delicate golden arrow, and the balloon popped, raining green goo mixed with tiny bits of writhing flesh.

“Jackpot!” people screamed.

I scrambled out of the way just in time to avoid being trampled.

The redhead shrieked, “See you in Faery!” Then she was on her hands and knees, licking the floor and fighting for pieces of Unseelie.

I looked around for Barrons again. At least I didn’t smell like fear. I was too disgusted and angry. I pushed through the press of sweaty, jostling bodies. This was my world? This was what we’d come to? What if we never got the walls back up? Was this what I was going to have to live with?

I began to shove people out of the way.

“Watch where you’re going!” a woman snapped.

“Chill, bitch!” some guy snarled.

“Are you asking for an ass-kicking?” a man threatened.

“Hey, beautiful girl.”

My head whipped around. It was the dreamy-eyed guy that had worked with Christian at the Ancient Languages Department at Trinity College, then had taken a bartending job at Chester’s when the walls fell.

The last time I’d seen him, I had a creepy experience, looking at his reflection in a mirror. But here he stood, behind a black-and-white bar walled with mirrors, tossing glasses and pouring shots with smooth, showy flair, and both he and his reflection looked every inch the perfectly normal young, gorgeous guy with dreamy eyes that melted me.

Though I was eager to see my parents, this guy kept showing up and I no longer believed in coincidences. My parents were going to have to wait.

I pulled up a stool next to a tall, gaunt man in a pin-striped suit and top hat, who was shuffling a deck of cards with skeletal hands. When he turned to look at me, I jerked and looked away. I did not look back again. Beneath the brim of his hat, there was no face. Shadows swirled like a dark tornado.

“Divine your future?” it said.

I shook my head, wondering how it spoke without a mouth.

“Ignore him, beautiful girl.”

“Show you who you are?”

I shook my head again, silently willing it to go away.

“Dream me a song.”

I rolled my eyes.

“Sing me a line.”

I angled my body away from it.

“You show me your face, I’ll show you mine.” Cards snapped together as it shuffled.

“Look, buddy, I have no desire to see—”

I broke off, physically unable to say another word. I opened my mouth and closed it, like a fish gasping for water, but I was gasping for words. It was as if all the sentences that I had been born with, enough to last a lifetime, had been sucked from me, leaving me utterly blank, silenced. The shape of my thoughts, the way I would phrase them, had been taken. Everything I’d ever said, everything I ever would say, it held now. I felt a terrible pressure inside my head, as if my brain was being vacuumed clean of who I was. I had the crazy thought that, in moments, I would be as blank behind my face as it was beneath its hat, leaving only a dark tornado, ceaselessly whirling, inside my skull. And maybe, just maybe, once it had everything it wanted from me, a fragment of a face would appear beneath its brim.

Terror gripped me.

I shot a frantic look at the dreamy-eyed guy. He turned away and poured a shot. I mouthed a silent plea at his reflection in the mirror behind the bar.

“I keep telling you not to talk to things,” the reflection of the dreamy-eyed guy said.

He poured and served, moving from one customer to the next, while my identity was erased.

Help me, my eyes screamed in the mirror.

The dreamy-eyed guy finally turned back to me. “She is not yours,” he told the tall, gaunt man.

“She spoke to me.”

“Look deeper.”

After a moment, “My mistake,” the card-shuffling thing said.

“Don’t repeat it.”

As abruptly as they’d vanished, I had words again. My brain was full of thoughts and sentences. I was a person, complete with ideas and dreams. The vacuum was gone.

I fell off my stool and stumbled away from the faceless man. On shaky legs, I tottered three stools down, hoisted myself back up, and clutched the counter.

“He will not bother you again,” the dreamy-eyed guy said.

“Whiskey,” I croaked.

He slid a shot of top-shelf whiskey down the counter. I slammed it back and demanded another. I gasped as fire exploded inside me. Though I wanted nothing more than to put a mile between myself and the card-shuffling monster, I had questions. I wanted to know how the dreamy-eyed guy could command something like that. For that matter, what was the faceless thing?

“The fear dorcha, beautiful girl.”

“Reading my mind?”

“Don’t have to. Question’s all over your face.”

“How does it kill?” I’m obsessed with the many ways the Fae dole out death. I make meticulous notes in my journal on the various castes and their methods of execution.

“Death is not its goal.”

“What is?”

“It seeks the Faces of Humanity, beautiful girl. Got one to spare?”

I said nothing. I had no desire to know more. Chester’s was a Fae safety zone. On my last visit to the club, it was made abundantly clear to me that if I killed anything on the premises, I would be killed. Since Ryodan and his men already wanted me dead, tonight probably wasn’t the best night to test my luck. If I learned more about it, or the killing weight of my spear in my shoulder holster grew any heavier, I might do something rash.

“Some things can’t be killed that easy.”

I glanced, startled, at the dreamy-eyed guy. He was looking at my hand inside my coat. I hadn’t even realized I’d reached for it.

“It’s Fae, right?” I said.

“Mostly.”

“So, how can it be killed?”

“Does it need to be killed?”

“You’d stick up for it?”

“You’d stick a spear in it?”

I raised a brow. Apparently, a prerequisite for working at Chester’s was that you had to like the Fae and be willing to put up with their unique appetites.

“Haven’t seen you in a while.” He changed the subject smoothly.

“Haven’t been around to be seen,” I said coolly.

“Almost weren’t just now.”

“Funny guy, aren’t you?”

“Some think so. How you been?”

“Good. You?”

“All in a day’s work.”

I smiled faintly. Barrons had nothing on the dreamy-eyed guy’s evasive answers.

“Gone light again, beautiful girl.”

“In the mood for a change.”

“More than the hair.”

“Suppose.”

“Looks good on you.”

“Feels good.”

“May not be useful. Times like these. Where you been?” He tossed a glass into the air and I watched it tumble lazily, end over end.

“In the Silvers, walking around the White Mansion, watching the concubine and the Unseelie King have sex. But I spend most of my days trying to figure out how to corner and control the Sinsar Dubh.”

The name of the Unseelie King’s Book seemed to hiss sibilantly through the air, and I felt a breeze as every Unseelie head in the club turned toward me in unison.

For a split second the entire club was silent, frozen.

Then sound and motion resumed with the tinkle of crystal as the wineglass the dreamy-eyed guy had been tossing hit the floor and shattered.

Three stools down, the tall, gaunt thing made a choking sound and his deck of cards sprayed the air, raining down on the counter, my lap, the floor.

Ha, I thought, got you, dreamy-eyes. He was a player in all this. But who was he and which team was he playing for?

“So, who are you really, dreamy-eyed guy? And why do you keep popping up?”

“Is that how you see me? In another life, would you take me to the prom? Home to meet the parents? Kiss me good night on the stoop?”

“I said, ‘Stay close,’ ” Barrons growled behind me. “And don’t talk about the bloody Book in this bloody place. Move your ass, Ms. Lane, now.” He took my arm and pulled me from the stool.

Cards spilled from my lap as I stood up. One had slipped inside the fur collar of my coat. I removed it and began to toss it away but at the last moment stopped and looked at it.

The fear dorcha had been shuffling a tarot deck. The card I held was framed in crimson and black. In the center, a Hunter flew over a city at night. The coast was a dark border for the silver sheen of the ocean in the distance. On the Hunter’s back, between great, dark flapping wings, was a woman with a soft tousle of curls blowing around her face. Between strands of hair, I could see her mouth. She was laughing.

It was the scene from my dream the other night. How could I be holding a tarot card with one of my dreams on it?

What was on the rest of the cards?

I glanced down at the floor. Near my feet was the Five of Pentacles. A shadowy woman stood on a sidewalk, peering through the window of a pub, watching a blond woman inside who was sitting at a booth, laughing with her friends. Me watching Alina.

On Strength, a woman sat cross-legged in a church, naked, staring at the altar as if praying for absolution. Me after the rape.

The Five of Cups showed a woman who looked startlingly like Fiona, standing in BB&B, crying. In the background I could see—I bent and peered closer—a pair of my high heels? And my iPod!

On the Sun were two young women sprawled in bikinis—one lime green, the other hot pink—soaking up the rays.

There was the Death card, a hooded grim reaper, scythe in hand, standing over a bloody body, female again. Me and Mallucé.

There was one with an empty baby carriage abandoned near a pile of clothing and jewelry. One of those parchment-like husks the Shades left behind protruded from the carriage.

I ran my hands through my hair, pushing it back as I stared down.

“Prophecies, beautiful girl. Come in all shapes and sizes.”

I glanced up at the dreamy-eyed guy, but he was no longer there. I looked to my right. Mr. Tall, Pin-striped, and Gaunt was also gone.

On the bar, beside a freshly filled shot and a Guinness, another tarot card had been placed with care, facedown, black-and-silver side up.

“Now or never, Ms. Lane. I don’t have all night.”

I tossed back the shot and chased it, then picked up the card and slipped it into my pocket for later.

Barrons steered me to a chrome staircase that was guarded at the bottom by the same two men that had escorted me to the top floor to see Ryodan the last time I was here. They were enormous, dressed in black pants and T-shirts, with heavily muscled bodies and dozens of scars on their hands and arms. Both carried snub-nosed automatics. Both had faces that drew the eye but, the moment you saw them, made you want to look away.

As we approached, they swung their weapons toward me.

“What the fuck is she doing here?”

“Get over it, Lor,” Barrons said. “When I say jump, you say how high.”

The one that wasn’t Lor laughed, and Lor slammed him in the gut with the butt of his gun. It was like hitting steel. The guy didn’t even flinch.

“The fuck I jump. In your dreams. Laugh again, Fade, and you’ll be eating your balls for breakfast. Bitch,” Lor spat in my general direction. But he didn’t look at me, he looked at Barrons, and I think that’s what pushed me over the edge.

I glanced between the two guards. Fade stared straight ahead. Lor glared at Barrons. I stepped away from Barrons and walked directly in front of them. Their gazes never wavered. It was as if I didn’t exist. I had no doubt I could stand there and do a dance, naked, and they’d still stare at anything but me.

I grew up in the Deep South, in the heart of the Bible Belt, where there are still a few men who refuse to look at a woman that isn’t a relative. If a woman is with a man they need to speak with—whether it’s her daddy, boyfriend, or husband—they’ll look at the man the entire time. If the woman asks a question and they bother answering at all, they direct their reply to the man. They even turn to the side a little, as if catching a glimpse of her in their periphery might condemn them to eternal damnation. The first time it happened to me, I was fifteen, and dumbfounded. I kept asking question after question, trying to get old man Hatfield to look my way. I’d begun to feel invisible. Finally I’d moved to stand right in front of him. He’d stomped off in the middle of a sentence.

Daddy had tried to explain to me that the old man considered it a kind of respect he was paying. That it was a courtesy given to the man the woman belonged to. I hadn’t been able to get past the words “the man the woman belonged to.” It was a property thing, pure and simple, and apparently Lor—who, according to Barrons, didn’t even know what century it was—was still living in a time when women had been owned. I hadn’t forgotten his comment about Kasteo, who hadn’t spoken in more than a thousand years. How old were these men? When, how, where had they lived?

Barrons took my arm and turned me toward the staircase, but I shook him off and turned back to Lor. I was getting way too much bad press. I wasn’t a stone. I hadn’t been created by the Unseelie King. And I wasn’t a traitor.

One of those things I could have a satisfying fight about.

“Why am I a bitch?” I demanded. “Because you think I slept with Darroc?”

“Shut her up before I kill her,” Lor told Barrons.

“Don’t talk to him about me. Talk to me about me. Or do you think I’m not worthy of your regard because, when I believed Barrons was dead, I hooked up with the enemy to accomplish my goals? How terrible of me,” I mocked. “I guess I should have just laid down and died with a whimper. Would that have impressed you, Lor?”

“Get the bitch out of my face.”

“I guess taking up with Darroc makes me pretty … well”—I knew what word Barrons hated, and I was in the mood to try it out on Lor—“mercenary, doesn’t it? You can blame me for that if you want to. Or you can pull your head out of your ass and respect me for it.”

Lor turned his head and looked at me then, as if I’d begun to speak his language. Unlike Barrons, the word didn’t seem to bother him. In fact, it seemed he understood, even appreciated it. Something flickered in his cold eyes. I’d interested him.

“Some people wouldn’t see a traitor when they looked at me. Some people would see a survivor. Call me anything you like—I sleep fine at night. But you will look at me when you say it. Or I’ll get so far in your face you’ll be seeing me with your eyes closed. You’ll be seeing me in your nightmares. I’ll scorch myself on the backs of your eyelids. Get off my back and stay off it. I’m not the woman I used to be. If you want a war with me, you’ll get one. Just try me. Give me an excuse to go play in that dark place inside my head.”

“Dark place?” Barrons murmured.

“As if you don’t have one,” I snapped. “Your cave makes mine look like a white beach on a sunny day.” Shouldering past them, I pushed up the stairs. I thought I heard a rumble of laughter behind me and glanced over my shoulder. Three men stared at me with the dead, emotionless gazes of executioners.

But, hey—they were all looking.

Behind a chrome balustrade, the upper floor stretched: acres of smooth dark-glass walls without doors or handles.

I had no idea how many rooms were up here. From the size of the downstairs, there could be fifty or more.

We walked along the glass walls until some tiny detail I couldn’t discern signified an entrance. Barrons pressed his palm to a dark-glass panel, which slid to the side, then he pushed me into the room. He didn’t step in with me but continued moving down the hall to some other destination.

The panel slid closed behind me, leaving me alone with Ryodan in the room that was the guts of Chester’s. It was made entirely of glass—walls, floor, and ceiling. I could see out, but no one could see in.

The perimeter of the ceiling was lined with dozens of small LED screens fed by cameras that panned every room in the club, as if you couldn’t see enough of what was going on merely by looking down past your feet. I stayed where I was. Every step you take on a glass floor feels like a leap of faith when the only solid floor you can see is forty feet below.

“Mac,” said Ryodan.

He stood behind a desk, couched in shadow, a big man, dark in a white shirt. The only light in the room came from the monitors above our heads. I wanted to launch myself across the room and attack him, claw his eyes out, bite him, punch him, stab him with my spear. I was astonished by the depth of hostility I felt.

He’d made me kill Barrons.

High on that cliff, the two of us had beaten, cut, and stabbed the man who’d been keeping me alive almost since the day I arrived in Dublin. And I’d wondered for days that had felt like years if Ryodan had wanted Barrons dead.

“I thought you tricked me into killing him. I thought you’d betrayed him.”

“I kept telling you to leave. You didn’t. You were never supposed to see what he was.”