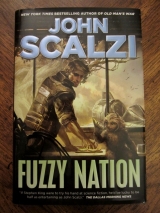

Текст книги "Fuzzy Nation"

Автор книги: John Scalzi

Соавторы: John Scalzi

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 11 (всего у книги 17 страниц)

“I misled Isabel by not telling her this,” Holloway said. “And thus by making her think that I disagreed with her about the sentience of the fuzzys, when in fact over the last few days I have become completely convinced of it. They speak, Ms. Meyer, Your Honor. They speak and discuss and argue and sing. That’s not a trick you can fake, no matter how clever an animal you are, or how clever you, as a human, might be with training animals. These aren’t just animals. These are people.

“And Dr. Wangai,” Holloway said, turning to Isabel again, “I was wrong. I was wrong to keep this information from you, and for allowing you to enter into this inquiry without all the facts you needed to defend your assertion, and for allowing anyone to cast doubt on your reputation. It was wrong. I was wrong for ever doing it or for ever allowing it. I am sorry.”

Holloway turned away from Isabel and sat back down in the witness stand.

“I’m done with my presentation,” he said, to the judge.

Chapter Eighteen

“This proves nothing,” Meyer said, once she had gained enough composure to begin again.

“It proves that we can’t immediately discount the idea that the fuzzys have speech,” Holloway said. “That’s something. It’s something fairly big.” “You could very well have taught them to make these sounds,” Meyer said.

“Are you suggesting that I created a hoax so byzantine that it includes teaching animals to speak something no one could hear?” Holloway said. “To what end, Ms. Meyer? If it was a trick to fool Isabel, then it failed, because she didn’t know of it until just a couple minutes ago.” “It’s a hoax to put the Zarathustra Company in an uncomfortable financial position,” Meyer said.

“Then it’s a hoax that also puts me in an uncomfortable financial position, because I stand to lose billions if the fuzzys are deemed sentient,” Holloway said. “I have a very distinct and obvious reason to hope the fuzzys are simply animals.” Meyer opened her mouth; Holloway held up his hand. “I know where you’re going next,” he said. “The only possible way this does me any good is if I’ve somehow set things up to short ZaraCorp stock on the market, in the hope of reaping the benefit when the stock price falls. But to forestall such an argument, I’m willing to give Judge Soltan complete access to all my financial and communication data for the last couple of years. She’s more than welcome to have forensics experts go through the data to look for evidence that I’m trying to manipulate ZaraCorp stock. But I can tell you right now that she won’t find it. My only financial holdings at this point are the royalties ZaraCorp automatically puts into my account at the Zarathustra Corporate Bank. I think I earn half a percent on that annually.” “But we have no way of knowing if these sounds are speech!” Meyer said. “You’re a surveyor, not an expert on xenosapience. And we’ve already established that Dr. Wangai has no formal training in xenosapience. Neither of you can even knowledgably guess at what those sounds mean.” Holloway saw Isabel’s eyes widen; she knew the hole Meyer had just fallen into. Holloway smiled. “You are quite correct, Ms. Meyer,” he said. “So I suggest we let someone who canknowledgably guess give an expert opinion. I suggest we call Arnold Chen.” “Who?” Meyer said.

“Arnold Chen,” Holloway repeated. “He received his doctorate in xenolinguistics. University of Chicago, I believe. He works in the same office as Dr. Wangai. Just down the street from here. I understand he was mistakenly assigned to Zara Twenty-three. Lucky for us he’s here.” “Is this correct?” Soltan said to Meyer.

“I don’t know,” Meyer said. She was thoroughly confused by the course of events.

“Excuse me, Your Honor,” Isabel said. “Jack’s correct. Dr. Chen is a xenolinguist. He’s also likely to be in his office right now.” “Doing what, exactly?” Soltan said.

“That’s a good question, Your Honor,” Isabel said. “I’m sure Dr. Chen would like to know what he’s supposed to be doing as well.” “Let’s bring him in,” Soltan said.

“If I may make a suggestion, Your Honor, have one of your clerks bring him in, rather than one of ZaraCorp’s people,” Holloway said.

“What is that supposed to mean?” Meyer asked.

“I think given the circumstances there is a reasonable chance someone might attempt to coach the expert,” Holloway said. “I can think of some examples in my own experience where such a thing was attempted.” Meyer kept quiet after that one, lips thinned.

“Fine,” Soltan said.

“I’d also suggest not telling Dr. Chen why he’s been called,” Holloway said. “Let him experience the video clean.” “Yes, all right,” Soltan said, irritated. “Any more suggestions on how I should do my job, Mr. Holloway? Or are you done now?” “Apologies, Your Honor,” Holloway said.

Soltan eyed Holloway sourly and then turned to Meyer. “Are you finished with this expert?” Soltan asked.

“I have nothing more to say to Mr. Holloway,” Meyer said. She eyed Holloway like he was a bug.

“Mr. Holloway, you are excused,” Soltan said. “We’ll take a fifteen-minute break while my clerks retrieve Dr. Chen.” She got up and went to her chambers. Meyer packed up her notes, flung them at her assistant, and stormed out of the court, assistant scrambling to catch up. Holloway noted that Landon had disappeared as well, no doubt to catch up his boss on the events of the day.

Holloway got out of the stand and was surprised to find Isabel in front of him. “Hello,” he said.

Isabel very suddenly gave him a large hug. Holloway stood there and took it, surprised; it had been a while since he had more physical contact with her than a polite peck on the cheek. Indeed, when Isabel stopped hugging him, she planted a kiss on his cheek that was more than polite. It was actually friendly.

“Apology accepted,” she said, stepping back. Sullivan by now had come up behind her.

“Well, good,” Holloway said. “Because if you didn’t accept that one, I would have given up.” “Thank you, Jack,” Isabel said. “In all honesty and sincerity, thank you.” “Don’t thank me yet,” Holloway said. “If it turns out the fuzzys are actually people, I’m going to be broke and out of a job, and then me and Carl are showing up on your doorstep.” “I’ll be sure to give Carl a good home,” Isabel said.

“Oh, nice,” Holloway said, and looked over to Sullivan. “You see how far good deeds get you in this life,” he said to him. Sullivan smiled but said nothing. He looked distracted. Isabel gave Holloway another quick peck and then did the same to Sullivan before leaving the courtroom.

Holloway turned his attention to Sullivan. “I’m out of the doghouse,” he said.

“If only you had managed it while the two of you were still dating,” Sullivan said.

“Yes, well,” Holloway said. “Let my misfortune be your example, Mark.”

“Jack, you and I need to talk,” Sullivan said.

“Is this about Isabel?” Holloway asked.

“No, not about Isabel,” Sullivan said. “It’s about everything else.”

“That’s a lot,” Holloway said. “I don’t think we have time to cover everything else besides Isabel in the next five to ten minutes.” “No, we don’t,” Sullivan said. “Let’s you and I go have a talk at the end of this little farce.” “Farce?” Holloway said, mock shocked. “This is a sober application of judicial wisdom.” Sullivan cracked a smile at this. “I don’t mind admitting to you that this is going differently than I expected,” he said.

“I don’t think you’re the only one thinking that at the moment,” Holloway said.

*

Dr. Chen was ushered into the courtroom by one of Soltan’s clerks. The xenolinguist looked confused, and depending on one’s observational inclinations, either freshly awoken from a nap or slightly drunk.

“Dr. Arnold Chen?” Judge Soltan asked.

“Yes?” Chen said.

“We are calling you to give testimony on a video that concerns a subject you are knowledgeable about,” Soltan said.

“This is about the other night, isn’t it?” Chen said. “I admit I drank too much, but I didn’t have anything to do with the rest of what went on.” “Dr. Chen, what are you talking about?” Judge Soltan said, after a minute.

“Oh, nothing,” Chen said, hastily.

Soltan peered at Chen. “Have you been drinking today, Dr. Chen?”

“No,” Chen said. He looked embarrassed. “I was, um.”

Soltan looked over at her clerk. “He was asleep at his desk when I found him,” said the clerk.

“Late night, Dr. Chen?” Soltan said.

“A bit, yes,” Chen admitted.

“But you are able to thinkright now?” Soltan asked. “Your brain processes are not currently compromised by alcohol or any other drug, recreational or pharmaceutical?” “No, ma’am,” Chen said. “Your Honor. Um.”

“Have a seat at the witness stand, Dr. Chen,” Soltan said. Chen took a seat. Soltan glanced over at Holloway. “You’re up, Mr. Holloway,” she said.

Holloway stood and borrowed Isabel’s infopanel once more, and opened a pipe between it and the monitor. “Dr. Chen, I’m going to show you a video,” Holloway said. “Don’t worry, the events of the other night aren’t on it.” Chen looked at Holloway blankly.

“Just watch the video and give us your impressions of it as it goes along,” Holloway said. He queued up the video of Papa, Mama, and Grandpa Fuzzy eating the bindi.

“What are those?” Chen asked, looking at the still image. “Are those monkeys? Cats?” “You’ll see,” Holloway said, and started the video.

Chen watched for a minute, thoroughly confused. Then it was like a 50,000-watt light went on in his head.

Chen looked up at Holloway. “Can I?” he asked, motioning to the infopanel. Holloway glanced at Soltan, who nodded. He handed the infopanel to Chen. The xenolinguist grabbed it and reversed the video and played the first parts again. He turned up the volume to hear better. He moved the video back and forth for several minutes.

Finally he looked up at Holloway. “You know what they’re doing,” Chen said.

“You tell me, Dr. Chen,” Holloway said.

“They’re talking!” Chen said. “My god. They’re really talking.” He looked back at the monitor. “What are these things? Where did you find them?” “Are you sure they’re talking?” Meyer asked from her table.

“Well, no, I’m not one hundred percentsure,” Chen said. “I’m just going from what you’re showing me here. I’d need to see much more to be certain. But, look—” He paused the video and backed it up slightly, and ran it again. “Listen to what they’re doing here. It’s phonologically varied but it’s not random.” “What does that mean?” Holloway asked.

“Well, look,” Chen said. Whatever sleepiness he’d had in him was well and truly shaken off now. “Take birdsongs. They repeat with very little variation. Phonologically they’re very consistent. They’re not what we typically consider language. Language uses a limited number of phonological forms—phonemes—but then it uses them in an almost infinite number of combinations, according to the morphology of the language. So, varied but not random.” Chen pointed to the conversing fuzzys. “What these little guys are doing is like that. If you listen, you can hear certain forms used over and again. Here—” Chen moved the video to another portion, where Papa Fuzzy was speaking. “—that tche-sound. It comes up a lot, but it’s joined to other sounds as well. Just like we use particular phonemes over and again, particularly ones that represent vowel forms in our language.” “So this is a vowel?” Holloway asked.

“Maybe,” Chen said. “Or maybe a prefix, since just listening here it always seems to precede other sounds. I couldn’t tell you what it means or represents.” “So it could just be noises they make,” Meyer said. “Like a cat’s meow. Or a birdsong.” “Well, neither cats nor birds vocalize just to vocalize,” Chen said, sounding slightly snotty. Holloway grinned. After years of having not a goddamn thing to do, Dr. Chen’s brain was back with a vengeance. “And no, I don’t think so. Your cat has a different sound for ‘I’m hungry’ and ‘I want out of the house’ but its vocabulary is not what you would call complex nor does the sound in itself convey complex meaning. Same with birdsongs. What these creatures are doing—the variation but apparently within a system—suggests that the sounds are words in themselves.” Chen looked up. “Is there more video?” “Lots more,” Holloway said.

Chen looked like a kid getting a puppy for Christmas. “Excellent,” he said.

“Dr. Chen,” Soltan said. “Is this language? Is this speech?”

“Are you asking for a determination?” Chen said. “Because I don’t have enough data.” “Guess, then,” Soltan said.

“If I had to guess, then, yes, sure,” Chen said. “And not just because of phonology and apparently morphology. Look at how the creatures react and respond to each other in this video. They’re clearly listening attentively and responding, not with rote or instinctual sounds, but with new patterns of sound. If it’s not language—if it’s not speech—then it’s something very close to it.” “Does it warrant further study, in your opinion?” Soltan asked.

Chen looked up at the judge like she was stupid. “Are you kidding?” he asked.

“You’re in my courtroom, Dr. Chen,” Soltan growled.

“I apologize,” Chen said. “It’s just that this is tremendously exciting. This is the sort of thing that you pray for as a xenolinguist. What are these things? Where are they from?” “They’re from here,” Holloway said.

“Really?” Chen said. Then it hit him. “Oh,” he said, looking around the room. “ Oh. Wow.” “Yes,” Holloway said. “Oh, wow.”

Soltan looked over to Meyer. “Any other questions for Dr. Chen?”

Meyer shook her head. She could see where this was going. Soltan excused Chen; Holloway just about had to tear the infopanel from his grip.

“Based on the information provided today, I’ve decided there is not sufficient cause to order the Zarathustra Corporation to file a Suspected Sapience Report,” Soltan said, after Holloway and Chen had sat down. “However, these creatures are from all evidence clearly something more than just animals. Whether they rise to the level of true sapient beings is a determination that no one here, with all due respect to Drs. Wangai and Chen, is able to state definitively. If there was ever a case in need of additional study, this would be it.

“I will be filing a request with the Colonial Environmental Protection Agency, under whose auspices sentience determination is administered, to dispatch the appropriate experts here for additional study and to make a decision regarding the sentience of the ‘fuzzys.’ Until that time, the Zarathustra Corporation will continue its normal operations, with the understanding that it will now conform to CEPA guidelines regarding exploitation of disputed worlds. I’ll be posting the inquiry ruling later today. Any objections, Ms. Meyer?” “None, Your Honor,” Meyer said.

“Then this inquiry is adjourned,” Soltan said. She rose and disappeared into her chambers.

Chapter Nineteen

Holloway was walking Carl, finding a good place for the dog to take care of his business, when Wheaton Aubrey VII appeared in front of him as if by magic.

Holloway peered around Aubrey. “Where’s your shadow?” he asked. “I wasn’t aware you were allowed to go anywhere but the bathroom without your body man.”

Aubrey ignored this. “I want to know why you pulled that stunt in the courtroom,” he said.

“I’m wondering what part of it constitutes the stunt for you,” Holloway said. “The ‘telling the truth’ part, or the ‘not telling you I was going to tell the truth’ part.”

“Cut the shit, Holloway,” Aubrey said. “We had a deal.”

“No, we didn’t,” Holloway said. “ Yousaid we had a deal. I don’t recall agreeing that we did. You assumed we did and I didn’t bother to correct your misapprehension.”

“Jesus,” Aubrey said. “You can’t be serious.”

“Jesus I am,” Holloway said. “And if you want to take it to court, you’ll find there’s quite a lot of case law that supports my point of view. Oral contracts are shaky enough as it is, but oral contracts in which one of the parties does not audibly and explicitly give consent to the agreement are not worth the sound waves they are spoken through. Not that you’ll be wanting to take this to court, of course. Encouraging perjury is not looked upon very kindly by any court I can think of. And while I don’t know if encouraging someone to perjure themselves at one of these quasi-legal inquiries constitutes a prison worthy offense, at the very least I would guess that it’s a slam-dunk that the supposed deal wouldn’t have legal standing in the first place.”

“Let’s assume for a moment that you and I both know that none of anything you just driveled on about matters one bit,” Aubrey said. “And let’s also pretend that both of us know what’s actually true here, which is that the last time you and I spoke, you had every intention of doing exactly what we had planned. All right?”

“If you say so,” Holloway said.

“Well, then,” Aubrey said. “I repeat: I want to know why you pulled that stunt in the courtroom.”

“Because they’re people,Aubrey,” Holloway said.

“Oh, bullshit, Holloway,” Aubrey spat. “We both know you don’t give a damn about whether they’re peopleor not, especially when you’re looking at billions of credits. You’re not built that way.”

“You haven’t the slightest idea how I’m built,” Holloway said.

“Apparently not,” Aubrey agreed, “because I assumed that despite all evidence to the contrary, you were capable of logical thought, and of working for your own advantage when necessary. Doing this doesn’t help you at all. The only thing it does is let you make nice with that biologist. I hope the pity sex you get out of that is worth the billions you just pissed away, Holloway.”

Holloway counted to five before replying. “Aubrey, you talk like someone who’s never gotten the shit beat out of him for being an asshole,” he said.

Aubrey opened his arms, wide. “Take your shot, Holloway,” he said. “I’d really like to see you try.”

“I already took my shot at you, Aubrey,” Holloway said. “You might recall. It’s why we’re having this little conversation right now.”

Aubrey put his arms back down. “This wasn’t about me,” he said.

“No,” Holloway agreed. “That was just one of the side benefits.”

“You know those fuzzy creatures of yours are never going to be found sentient,” Aubrey said.

“I’m well aware you’re going to throw a lot of resources into making the case against them,” Holloway said. “Which is not the same thing.”

“We’re going to make that case,” Aubrey said.

“Then you’re out the relatively minimal cost of the legal proceedings and your paid experts and what have you,” Holloway said. “For ZaraCorp, that’s next to nothing. You, Aubrey, probably make more in interest off your share of the company each day. So what. But if you don’tmake the case, then the fuzzys have the right to their own planet, in which case all of this is immaterial, and you should consider what you have stripped off the planet a gift, rather than your right. You really can’t complain.”

“I still don’t understand why you did it,” Aubrey said.

“I already told you why,” Holloway said.

“I don’t believe you,” Aubrey said.

“As if I careabout that,” Holloway said. “Look, Aubrey. It could take the experts years to make a determination. If you have your way with your own lawyers and experts, that will certainly be true. In which case you still have years to exploit the planet. More than enough time to prepare your company and your stockholders.”

“Or they might make a determination within months,” Aubrey said. “In which case the company is screwed.”

Holloway nodded. “Then I suggest you prioritize your efforts,” he said. “You’ve said yourself that sunstone seam I found is worth decades of revenues for ZaraCorp. If I were you, I’d be putting just about everything I could into it.”

“It’s already our top priority,” Aubrey said.

“Now it’ll be your top priority with a special sense of urgency, won’t it,” Holloway said.

Aubrey suddenly grinned, grimly. “ NowI understand why you did it, Holloway,” he said. “Having us exploit the sunstone seam in our usual way wouldn’t get you rich enough fast enough. You wanted as much as you could get as quickly as you could get it. So you show Judge Soltan just enough of your little talking monkeys to force her to rule for more study—but not enough so that she requires us to file an SSR. Zarathustra Corporation is put into the position of having to focus on the single most profitable project on the planet, which you just happento have discovered.”

Holloway said nothing to this.

“This proves you don’t actually give a shit about those little fuzzys of yours,” Aubrey said. “You’ll still get your percentage of the sunstone seam whether the experts decide the fuzzys are sentient or not. You’ve played your biologist friend, and you played ZaraCorp at the same time. Very nicely done. I can almost admire it. Almost.”

“It’s not as if ZaraCorp won’t see the benefit of it,” Holloway said. “If you exploit that seam quickly, you’re creating an endowment for your company. You hold the monopoly on sunstones. You can store those sunstones and dribble them out over decades, whenever you need an extra boost to the bottom line. That I get my bit up front is neither here nor there.”

“We have a monopoly only if the fuzzys are found not to be sentient,” Aubrey said.

“You have a monopoly either way,” Holloway said. “As I mentioned to someone else recently, the fuzzys only recently discovered sandwiches. Sentient or not, there’s no way they’re going to be ready to handle the world of interplanetary business. It’s unlikely the Colonial Authority will allow them to for decades. It was only a decade ago the CA decided the Negad were competent enough to enter into resource deals on their own planet. The fuzzys are far behind where the Negad were when they were declared sentient. ZaraCorp’s monopoly isn’t going anywhere anytime soon.”

“It will still cost us hundreds of millions of credits to refocus all our planetary resources on that seam,” Aubrey said.

Holloway shrugged, and the message was clear enough: Like I care.

“And we might decide not to,” Aubrey said.

“I understand the Aubrey family doesn’t see fit to give ZaraCorp voting stock to the plebian masses,” Holloway said. “But the folks who own class B stock in the company can still sell it when they see the corporate governance doing something stupid. Like, say, not exploiting a sunstone seam that’s arguably worth the rest of the entire planet combined, when there’s an excellent chance the entire planet will soon be placed off-limits to future exploitation. The only real question in that case is how low the stock will go. I’d guess not quitelow enough for Zarathustra Corporation to get delisted. But one never does know, does one.”

Aubrey smiled another mirthless smile. “You know, Holloway, I’m delighted that the two of us have had this little chat,” he said. “It has put so many things into perspective.”

“I’m glad it has,” Holloway said.

“I don’t suppose you have any other surprises you want to share with me,” Aubrey said.

“Not really,” Holloway said.

“Of course not,” Aubrey said. “They wouldn’t be surprises then, would they.”

“The man has a learning curve,” Holloway said.

“One other thing,” Aubrey said. “I’ve decided that when your contract runs out, I’m going to have ZaraCorp renew it. All things considered, I think you’ll do us less damage here than anywhere else. And I want you where I can keep track of you.”

“I appreciate the vote of confidence,” Holloway said. “I don’t suppose you still plan on giving me that continent, though.”

Aubrey walked off.

“Didn’t think so,” Holloway said. He turned to Carl. “There goes a real piece of work,” he said to his dog.

Carl returned the comment with a look that said, That’s nice, but now I really do have to pee. Holloway continued their walk.

*

“You’re late,” Sullivan said, as he answered his door.

“I got waylaid by a very pissed-off future Chairman and CEO of Zarathustra Corporation,” Holloway said.

“That’s an acceptable excuse,” Sullivan said, and then glanced down at Carl, who was lolling his tongue at the lawyer.

“I promised Isabel I’d bring Carl around,” Holloway said. “I assumed she’d be here.”

“She’ll be around a bit later,” Sullivan said. “Why don’t you both come in.” He stood aside from the door.

Sullivan’s apartment was the standard-issue Zarathustra Corporation off-planet living space: twenty-eight square meters of floor plan divided into living room, bedroom, kitchen, and bath. “I think it’s disturbing my cabin is larger than your apartment,” Holloway said, entering.

“Not that much larger,” Sullivan said.

“Higher ceiling, in any event,” Holloway said, looking up. He could place his palm flat on the ceiling if he wanted to.

“I’ll give you that,” Sullivan said, walking through the front room to the kitchen. “You also don’t have an intern living above you playing noise until the dead hours of the morning. I swear I’m going to make sure that kid never gets another job with the company. Beer?”

“Please.” Holloway sat, followed by Carl.

“So what did Aubrey waylay you about?” Sullivan asked. “If you don’t mind me asking.”

“He asked me what I was thinking in the courtroom today,” Holloway said.

“Funny,” Sullivan said, coming back into the living room and handing Holloway his beer. “I was thinking of asking you the same thing.”

“Probably not for the same reasons, however,” Holloway said.

“Probably not,” Sullivan said. He twisted the cap off his own beer and sat. “Jack, I’m about to tell you something I shouldn’t,” he said. “The other day Brad Landon came into my office and told me to draft up an interesting sort of contract. It was a contract ceding operational authority for the entire northwest continent of the planet to a single contractor, who in return for handling substantial operational and organizational tasks for ZaraCorp, would receive five percent of all gross revenues.”

“That’s a nice gig for someone,” Holloway said.

“Yes it is,” Sullivan said. “Now, I was instructed to design the contract so that unless certain stringent production quotas were met, the contractor got very little, but you’ll understand that ‘very little’ in this case is a distinctly relative term. Whoever got this gig would be rich beyond just about any one person’s ability to measure wealth.”

“Right,” Holloway said.

“So I’m wondering why you just threw that away today,” Sullivan said.

“You don’t know that contract was meant for me,” Holloway said.

“Come on, Jack,” Sullivan said. “I think you’ve figured out by now that I’m not stupid.”

“Are you asking me this question as ZaraCorp’s lawyer or Isabel’s boyfriend?” Holloway asked.

“Neither,” Sullivan said. “I’m asking you as me. Because I’m curious. And because on the stand today you did something I didn’t expect.”

“You thought I was going to sell Isabel out,” Holloway said.

“Not to put too fine a point on it, but yes, I did,” Sullivan said. “You stood to make billions and you let it slip past you. Given your past history, you don’t strike me as the overly sentimental type. And, no offense, you’ve sold out Isabel before.”

“None taken,” Holloway said. “It wasn’t about Isabel.”

“Then what was it about?” Sullivan asked.

Holloway took a slug of his beer. Sullivan waited patiently.

“You remember why I was disbarred,” Holloway said.

“For punching that executive in the courtroom,” Sullivan said.

“Because he was laughing at those parents in pain,” Holloway said. “All those families were torn up to hell, and Stern felt comfortable enough to laugh. Because he knew at the end of the day our lawyers were good enough to get him and us out of trouble. He knew he’d never see the inside of a prison cell. I felt someone needed to send him a message, and I was in the right position to do just that.”

“And this relates to our current situation how?” Sullivan asked.

“ZaraCorp was planning to steamroll over the fuzzys,” Holloway said. “It was planning to deny the fuzzys their potential right to personhood on no more basis than because it could, and because the fuzzys were in the way of expanding their profit margins. And you’re right, Mark. I stood to profit quite handsomely myself from the whole business. It was in my interest to go along.”

“Very much in your interest,” Sullivan said.

“Yes,” Holloway agreed. “But at the end of it I have to live with myself. It was wrong of me to punch Stern in the courtroom, but I didn’t regret it then and I don’t now. ZaraCorp might eventually show that the fuzzys aren’t sentient, but if they do, at least they’ll do it honestly, and not just because I went along with them and made it easy for them. Maybe what I did today wasn’t the smart thing to do, but if nothing else, ZaraCorp isn’t laughing at the fuzzys anymore.”

Sullivan nodded and took a drink of his own beer. “That’s very admirable,” he said.

“Thanks,” Holloway said.

“Don’t thank me yet,” Sullivan said. “It’s admirable, but I also wonder if you’re not completely full of shit, Jack.”

“You don’t believe me,” Holloway said.

“I’d like to,” Sullivan said. “You talk a good game, and it’s clear your lawyer brain has never completely turned off. You’re good at presenting a scenario in which you always end up, if not the good guy, at least the guy with understandable motives. You’re persuasive. But I’m a lawyer too, Jack. I’m immune to your charms. And I think underneath your rationalizations there are other things going on. For example, your story about why you punched Stern in that courtroom.”

“What about it?” Holloway asked.

“Maybe you did do it because you couldn’t stand the sight of him, or the idea of him laughing at those parents,” Sullivan said. “But on a whim, I also checked the financial records of your former law firm. Turns out that two weeks before you punched Stern, you received a performance bonus of five million credits. That’s more than eight times your previous highest performance bonus.”

“It was my share of a patent infringement settlement,” Holloway said. “ Alestria versus PharmCorp Holdings. And others got bigger bonuses out of that than I did.”

“I know, I read up on the bonuses,” Sullivan said. “But I also know most of the big bonuses were paid out a couple months before yours was. Yours is interestingly timed. And it’s enough for a corporate staff lawyer to contemplate disbarment and the loss of his livelihood with a certain cavalier lack of concern.”