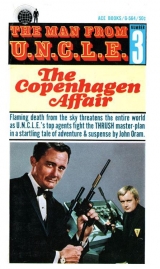

Текст книги "The Copenhagen Affair"

Автор книги: John Oram

Жанры:

Боевики

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 6 (всего у книги 7 страниц)

CHAPTER ELEVEN

THE OLD-FASHIONED clock was striking three when Illya and Sorensen walked into the farmhouse living room and took off their heavy jackets.

The two men sitting at the table looked up moodily. Illya said, “The bombs are disarmed. We placed a couple of charges and blew in enough of the mine entrance to keep out intruders. Any news of Karen?”

Solo spread his hands hopelessly. “We’ve moved heaven and earth to trace Garbridge’s call. No dice. The truck—or what might have been the truck—was seen once, heading toward Silkeborg. And the man who saw it, a farm-hand, was more than half-drunk. He can’t tell us a thing. Every policeman and every agent between Aalborg, Esbjerg and Sonderborg is on the job. We’ve alerted the airports and the harbormasters and coast guard. And nobody’s come up with a whisper. I don’t have to tell you that Jorgensen’s fit to be tied.”

“There must be something we can still do,” Viggo muttered. “Something we have overlooked.”

Illya looked at his watch. “Five after three. Only four hours left. You think he’s told her?”

“That’s a bet you can play on the nose. He wouldn’t—” High-pitched bleeping stopped him suddenly. He snatched the two-way transmitter from his pocket and tuned in.

A voice came faintly through the amplifier: “Come in, Solo. Come in, Solo.”

“Karen!” They yelled it simultaneously. Viggo slapped Knud so hard across the shoulder that the little man almost fell.

Solo turned the tuner to full volume. “Are you all right? Where are you?”

They heard her say, “I’m fine—for the moment. I’m in a phony maternity home, the SOLLYS, just inside Horsens. It’s on the right, off the main road. I don’t know the street.”

“Garbridge?”

“He’s here.” Her voice faltered. “He’s got plans for my future.”

“I know. How many more in the place?”

“I’ve only seen two—a kind of butler and a female homicidal maniac. But there must be others. Send the Seventh Cavalry. The Indians are hostile.”

Solo said briskly, “We’re coming—at a gallop. Tune your transmitter onto the homing beam and leave the rest to us.”

Illya, Viggo and Knud were ready and waiting. Illya was slipping a fresh magazine into his Luger and humming some kind of Russian war-song. Solo grabbed up his anorak and headed for the door.

They piled into Viggo’s big Volvo, Solo beside the driver and Knud and Illya in the rear seats. Solo put the little transmitter in the glove compartment in front of him. The continuous note of the homing signal sounded loud and clear.

“That,” said Viggo, as he let in the clutch, “is the sweetest Christmas carol I ever did hear.”

Illya warned soberly, “Don’t cheer too soon. We’ve got a long way to go.”

The big headlights cut tunnels of light in the blackness. Snowflakes danced in the beams like a hundred million fireflies and drove against the windshield to make little hillocks at the base. Viggo started the wipers swinging. The engine crooned sweetly, eating up the miles of highway.

Karen felt considerably happier. The talk with Solo had brought back all her confidence. She set the dials to homing, got off the bed and slipped the transmitter between the mattress and the box spring. She tucked the edge of the dyne back inside the raised frame of the bedstead and smoothed the surface neatly.

For the first time she was able to examine the room thoroughly. Besides the bed it contained no furniture but a white chest of drawers, a straight-backed chair and a washbasin with chrome-plated taps. There was one big window, set high in the cream-washed wall and draped with bright chintz curtains.

She set the chair below the window, climbed up and looked out. She could see nothing but the darkness of the night and her own dim reflection in the pane. She tried the catch, and to her surprise, it gave. Very gently, she eased the window open. Wind blew cold on her face. She looked down. The ground, illuminated by light from other windows, was a sheer drop far below. She was on the top floor of the house. There was no possible escape in that direction; the best she could hope to get was a broken neck.

Even that, she reflected, would be better and more merciful than the fate that waited her in the “labor ward”. If Solo failed to get through, a dive might be the answer. The end at least would be quick and clean.

If this had been the United States, she might have made a rope with blankets and got away. But Danish sleeping habits are different. You can’t do much with eiderdown and a sheet in the way of fixing an escape route.

She climbed down from the chair and went over to look at the door. The lock was of the ordinary ward type. She knelt and squinted through the keyhole. The light from the passage shone through clearly. The key had been removed. She felt a sudden hope.

The bulb that hung from the ceiling fixture had a conical parchment shade. With the aid of the chair she detached it and removed the wire stiffener from the rim. She straightened the wire and twisted it back and forward between her fingers until she had succeeded in breaking off a piece about six inches long. She bent it to the right shape and went back to the door. After several attempts the tongue of the lock snapped back. Karen opened the door cautiously and listened. In a few seconds, reassured, she slipped through into an empty corridor. The floor, to her relief, was carpeted. She made her way silently to the head of a stairway and started down.

The staircase formed a square well. Looking over the banisters, Karen saw that she had two more floors to negotiate before reaching the hall. She went forward quickly, keeping close to the wall to avoid the danger of creaking treads.

At the foot of the first flight she stopped to listen again. Footsteps tapped busily on parquet. She looked down and saw Sister Ingrid going into the major’s study. She waited until the door had closed behind the squat figure before going on again.

By the time she reached the hall beads of sweat were running down her backbone. The major’s door was still shut, but peering around the angle of the wall she could see the uniformed man asleep at the receptionist’s desk. The front door was less than fifty feet away. It was bolted top and bottom and there was a heavy lock of cylinder pattern at breast-height. Even if she got past the watchdog safely it was going to be quite a trick to get the door open without noise.

She took off her shoes and stuffed one into each pocket of her ski-pants. The short stretch of parquet suddenly looked like a limitless sea. She took a deep breath and ran for it.

Her hand was on the top bolt, forcing it back, when a voice snapped, “Leaving us?”

She whipped around, flattening against the door in a useless posture of defense.

Garbridge was standing, Luger in hand, in the door way of his study. Beside him Sister Ingrid smiled benevolently.

Garbridge was not smiling. His face, grown haggard during the strain of the past hours, was set in an ugly scowl.

“Get her over here,” he shouted at the uniformed man, who had stumbled to his feet and was standing apprehensively by his overturned chair. “Hurry up, you dolt. Do you think this is a dormitory?”

The man, still not properly awake, shambled across to Karen, grabbed her by the upper arms and pushed her toward the couple in the doorway.

Garbridge had been drinking; Karen could smell the fumes of whisky. The hand that held the Luger was not quite steady. The amber eyes had lost their cold, hard brightness.

He said thickly, “You never give up, do you? Well, you’ve asked for it, and by God, you’re going to get it. I’m taking no more chances.”

He looked at the watchman and jerked his head. “Take her down.”

Sister Ingrid said in her little-girl voice, “Til fodselsstuen?”

“Where else?”

He turned and went into the study, slamming the door behind him.

Sister Ingrid trotted happily toward the elevator gate. She stood there with her finger on the button, beckoning with the other plump hand for the uniformed man to hurry.

As the elevator door glided open Karen kicked backward viciously, trying to knock the guard’s legs from under him. He slipped, but regained his balance quickly. He shifted his grip, forced her arm up and back in a hammer-lock, and almost threw her into the cage of the elevator. Sister Ingrid crooned, “Quietly, quietly, elskede! We are going to enjoy ourselves, you and I.”

The lift whined downward, came to a stop at the basement level. The door slid open and Sister Ingrid ran ahead, fumbling at the châtelaine hanging from her belt for the key of the “labor room”. She was murmuring to herself delightedly as she turned the lock.

The man pushed Karen into the room, still holding her firmly. He asked, “Where do you want her?”

“On the operating table, if you please. That’s right. That’s right. Now, the straps…”

She began to pull the buckles tightly. Thin lines of saliva had begun to dribble from the corners of her tiny rosebud mouth.

The guard’s face had turned to the color of old dough. He said shakily, “Do I have to stay?”

“No, no. That would never do. We must be quite alone. Mother’s little baby has been naughty, and she must be corrected, you see.”

The blue eyes behind the steel-bowed spectacles were quite, quite mad.

CHAPTER TWELVE

THE VOLVO DECREASED speed. Viggo said, “We’re coming into Horsens now. Keep a sharp lookout for the side road.”

“In this blizzard,” Illya grumbled, “we’ll be lucky if we manage to hit the town.” There were now almost four inches of snow on the highway and flakes large as kroner pieces were beating onto the windshield, almost obscuring vision.

The steady piping of the homing signal weakened. Solo said, “We’re off-beam. We’ve missed the turn somehow. We’ll have to go back.”

Viggo swung the car in a U-turn, risking the chance of another vehicle on the road. The signal grew stronger again and after a minute Solo cried, “There!”

They turned down the side road. Illya rolled the window down and peered out, his eyes slitted against the snow-filled wind which slashed his face like a knife. A big sign ahead shone white in the headlights. He said, “Stop the car. This is it.”

Viggo braked, killed the engine and switched off the headlights. The men got out stiffly, cramped after the long, cold run.

The gates to the drive were locked. Using his flashlight, Illya found a porter’s bell set into one of the pillars. “Shall I ring it?” he asked. “Maybe they’ll think we’re expectant mommas.”

“Leave it alone,” Solo said. “We’ll go in over the wall.”

“After you!” Illya bowed jauntily, then bent and made a step with his linked hands.

Solo caught the top of the wall, pulled himself up and dropped noiselessly to the ground on the other side. The others followed him, one by one. He whispered, “Get right onto the drive. The lawn is probably trip-wired.” Not a light showed as they walked up to the house.

The place might have been empty. But the bleep of the transmitter, now muffled inside Solo’s coat, was still distinct.

They circled to the back of the building. There, too, all was in darkness. Solo found what looked as if it ought to have been the door to the kitchen quarters. He inserted a slim plastic tube into the lock and lit the end with his pocket lighter. There was a momentary, brilliant flash and a smell of burning metal. He pressed gently and the door opened.

His torch beam danced around the room, coming to rest briefly on an electric range, a refrigerator and a white wood table. Another door was let into the farther wall. A thin thread of light showed beneath it.

“Wait,” Solo whispered to the others. Taking great care to avoid the table and other obstacles, he crossed the room and listened at the door. There was no sound. He turned the handle. The door let out into a short passage where white jackets hung on hooks. Beyond the passage he could see the entrance to an elevator, and beyond that a section of hall where a gaily decorated Christmas tree towered beside a desk.

He winked the flashlight three times, and the other three joined him.

“All clear, so far,” he said. “Now the trick is to find where everybody’s hiding.”

He drew the Luger from its place under his left arm and slipped the safety catch.

They had gone only a few steps along the passage when the whine of the elevator stopped them in their tracks. They flattened against the wall.

The elevator door opened. A man in uniform stepped out. His face was paper-white. He walked unsteadily toward a big bowl of flowers standing on a side table. He wrenched the flowers out of the bowl and threw them onto the parquet. Then he put his head over the bowl and was thoroughly, enthusiastically sick.

The jolt of Knud’s twin gun barrels in his kidneys brought him upright abruptly. Knud said softly in Danish, “Make one sound and I’ll blow your back out. Over here, friend, quickly.” He prodded the man toward the passage.

Solo said, “Take him into the kitchen.”

He followed them, pushing the door shut behind him. “Now, talk,” he said, keeping the flashlight beam full on the man’s frightened face. “Where’s Garbridge?”

Knud translated, and the man gasped, “In his study, off the hall.”

“Alone?”

“Yes, sir.”

Solo said, “Viggo, go and take care of him. Don’t kill him unless you have to.” Then to the man,“ How many of you are there?”

Knud listened and said, “He claims that he and some crazy nurse are the only ones left except Garbridge. The rest are gone.”

“Ask him about Karen. Where are they holding her?”

The man gabbled almost incoherently, stabbing toward the floor with his finger. Knud’s eyes widened comically. He said, “Hvad?”

The man stammered again, “Fodselsstuen! Fodselsstuen!”

Knud said, “I don’t get it. He keeps repeating that she is in the labor ward. He says that’s what made him sick.”

Illya repeated incredulously, “The labor ward? Karen?”

“Ja, ja! Ganske vist.” The man tried frantically to get his meaning home. “Gestapo! De forstaar? Tortur!”

“Torture!” Solo didn’t need that translated. He said, “Tell him to get us there fast.”

With Knud’s scattergun still at his back, the man hurried them to the elevator. As the cage opened on the basement floor they heard a girl’s agonized scream.

Solo put his pistol to the lock of the door and fired three times. They burst into the room together.

Sister Ingrid rushed toward them. She was holding what looked like a white-hot soldering iron.

Illya shot her between the eyes.

Karen had lapsed into unconsciousness. Looking at what had been done to her, Solo knew that was just as well.

Illya asked dully, “Is she dead?”

“No, thank God. But she’s taken plenty. Stay with her, Illya. I’ll send Viggo down with some bandages.”

He nodded. “I’ll see to her.” He started gently to unbuckle the straps that bound her to the couch.

The uniformed man was still cowering under Knud’s shotgun. Solo looked at him contemptuously. He asked, “Do you think we could trust him?”

“As far as you could trust a hyena,” Knud said. “But there’s no fight in him, if that’s what you mean.”

“That’s roughly it. Tell him we need a first-aid kit down here right away. He’ll know where they keep the stuff. Tell him to bring it, and fast.”

They got back into the elevator and rode up to the ground floor. A jab with the gun barrels sent the man down the corridor on the double. Solo and Knud went along the hall to the major’s study.

Garbridge was sitting in his chair, hands on the desk in front of him. A whisky bottle, half empty, and a glass stood near his right hand. Viggo sat facing him across the desk, the Mauser gripped in his big fist.

Garbridge said, “Ah! Solo. I was expecting you. I trust you reached our little Karen in time?”

Knud started toward him, cursing. His shotgun came up, his fingers tightening on the trigger.

Solo grabbed his arm, forcing the gun down. “Easy! Don’t let him needle you.”

Garbridge raised a hand protestingly. “Indeed, you wrong me, Solo. I never approved of the methods of the late Sister Ingrid—I assume she is ‘late’? Yes, I thought so! The impetuous Mr. Kuryakin, no doubt—but there are times when such crudity is inevitable.” He shook his head. “You really should have accepted my offer. Now, I fear, we all have our little troubles.”

“Your troubles are not going to be little ones,” Solo said grimly. “You’re through, Garbridge.”

“I’m afraid so,” he admitted. “You have me over the—er—proverbial barrel. I suppose the only question is where I’ll stand trial and on what charges.”

“You’ll be handed over to the Danish authorities in Copenhagen. After that it’s out of my hands.”

“I thought so. By the way, would you very much mind if I stood up? Mr. Jacobsen, here, takes his duties very seriously, and I am getting a little cramped.”

“Suit yourself—but keep your hands where we can see them.”

“Thank you.” He got out of the chair and began to pace the room, hands clasped dutifully behind his back.

Solo said, “All right, Viggo. We’ll take over. You’ll find the porter, or whatever he is, waiting by the elevator. He’ll take you to Illya. Karen needs a little help.”

“You know, Solo,” Garbridge said, “I am genuinely glad you found Karen before it was too late. I was grieved for her.”

“I can imagine.”

“No, no. I mean it. She was beautiful. Perhaps,” he continued musingly, “that is from what all my past—er—mistakes have stemmed. I have loved beauty too much. Human beauty. The beauty of inanimate things. Like these…”

He picked up a Royal Copenhagen vase and ran his fingers caressingly over its smoky-blue surface as though it were a woman’s cheek. “They have been my friends, and”—he grinned suddenly—“they will be my friends now!”

Before Solo or Knud could move he had dashed the vase to the carpet. It burst like a bomb, filling the room with clouds of choking, blinding smoke.

Sorensen let go with both barrels of the scattergun. He was too late. When the smoke thinned the major was gone. A black opening gaped where his chair had stood. From somewhere beneath their feet came the roar of a powerful car engine.

Knud cursed and ran toward the door. But Solo stopped him.

“Let him go,” he said. “Whatever happens he’s finished. Thrush has no time for failures. If we don’t pick him up, he’s a dead man anyway. Meanwhile, we still have some pieces to pick up around here.”

Illya met them in the hall. He looked happier. Solo asked, “Karen?”

“We’ve moved her to a room upstairs. Viggo is with her and an ambulance is on its way. She’ll be okay. What was the shooting about?”

Solo said ruefully, “Garbridge. He had a neat line in potted smokescreens. And a fast car in the basement. Where’s the porter?”

“Long gone. He brought Viggo down to the basement, then while we were busy with Karen, took a powder.” He grinned. “Well, here we go again. Let’s toss for who does the calling-all-cars bit.”

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

SOLO LOOKED moodily out of the window of the office on the Borgergade at the snow-clad Abbey church. The building, a thirteenth-century Franciscan monastery, was one of Horsens’ proudest showpieces. But Solo was not in a state of mind to appreciate its beauty. He was deathly tired, and he had just talked by telephone with Mr. Alexander Waverly in New York.

Perhaps “talked” is the wrong word. He had spent most of the time listening. Waverly was audibly displeased, and he had made good and sure that his chief enforcement agent understood it.

His final words had been, “Mr. Solo, you will find this man Garbridge, and you will find him quickly.” Then the line had gone dead.

Not one word of praise or credit for the fact that the Danish satrap of Thrush had been broken, that the mystery of the flying saucers had been solved and the factory put out of action. The job had not been completed. Garbridge had been allowed to get away.

Not for the first time in his career Solo wondered: What did the man want? What kind of infallible perfection did he expect from ordinary, fallible subordinates?

Within minutes of Garbridge’s escape from the maternity home a dragnet had been tightened throughout Jutland, covering roads, harbors and airports. There were mobile police patrols on every highway and every secondary road that the blizzard had left negotiable. Helicopters were squaring the miles of lakeland and forest. But again the major had vanished as smoothly and completely as the stooge in a conjurer’s trick cabinet. And they did not know even the type of car in which he had driven out of the underground garage.

Illya came into the office, blowing on his half-frozen fingers. He had been to the hospital to see Karen.

“How is she?” Solo asked.

Illya smiled. “Sitting up and fighting mad. Says she’s perfectly fit and resents being treated like a cripple. When I left, she was shouting for her clothes and threatening to walk out in her panties.”

“It figures. But how bad is she hurt?”

“Not too much. A couple of nasty burns in awkward places. Some weals. She should be out in a day or two. We got there in time.” He flopped into a chair, spraddling his long, thin legs. “What I could do with some sleep!”

Solo nodded. “When I feel like this I sometimes think everything would be all right all over the world if everybody could get a good night’s sleep—”

The telephone on the desk shrilled. Solo grabbed the receiver.

He listened, then said, “Where? All right. We’re on our way.”

Illya sat up. “What was that all about?”

Solo was getting into his anorak. He said, “A Mercedes crashed a roadblock on Highway 18, three kilometers south of Herning. They took a shot at it. It swerved but didn’t stop. But a patrol outside Silkeborg found it overturned in a drift. That’s where we’re going.”

They clattered down the stairs and out into the Citroen parked by the curb.

“It’s a pity we let Jacobsen and Sorensen go,” Illya said, as he slid behind the wheel. “Right now we could have used the Volvo.”

Solo said, “What could I do? It’s not their fight.”

“And cows need regular valeting. I know. I’m an old farming type myself. But it’s still a shame.”

Solo didn’t hear him. He had fallen asleep.

A patrol stopped the car at the intersection of the A13 and A15 about twelve kilometers west of Silkeborg. Illya showed his identity card and asked, “Where’s the pileup?”

The policeman said, “A kilometer up the road. The inspector is waiting for you.”

“Thank you.” Illya jolted Solo with his elbow, not too gently. “Wake up, Goldilocks. Time for your porridge.” He turned the nose of the car to the right.

A huddle of men showed up black against the snowy landscape. Beside them was the broken silhouette of an upturned car, its front wheels and hood hidden in a deep drift.

Illya cut the Citroen’s engine. As they got out, a policeman wearing inspector’s insignia came forward to greet them.

They shook hands in the formal Danish fashion. Nothing in Denmark, even a funeral, can proceed without handshakes all round. Then they walked over to the car.

Solo asked, “Any sign of the driver?”

“No,” the inspector said. “As you see, there are bullet holes in the windshield and in the gas tank, and there is blood on the back of the front seat. That is how my men found it. The car was empty.”

“Footprints?”

“None. The snow has covered them. But the driver cannot have got far. It is plain he was wounded in the shooting at the road block. And even for a well man”—he swung his arm toward the desolate hills—“it would not be good conditions.”

“You’ve got men searching?”

The inspector looked hurt. He said, “Of course. This is first steps, nej? Also there is a helicopter, now the snow stops.”

Illya asked, “He couldn’t have made it into Silkeborg?”

“I think that is not likely. Would a wounded man wish to show himself in the streets? And where would he hide himself?”

“This character,” said Illya bitterly, “could hide himself in a perspex bag.”

A young policeman came floundering through the snow from the direction of a beech wood. He looked agitated.

The inspector said, “This is one of the searchers. I think he has news.”

The man came up and saluted. He spoke rapidly in Danish. The inspector’s face hardened.

He told them, “This is very bad. There is a farm beyond that wood there—a small place run by one old man. My officers have found him shot dead, and his car is gone from the garage. Do you wish to come with me?”

Solo said, “There’s not much point. Garbridge wouldn’t hang around, once he had transport. How many ways out of the farm are there?”

“One only. A very small road, little more than a track. It bypasses Silkeborg, coming out onto the A15 in the direction of Aarhus.”

“But that’s crazy,” Illya said. “Your patrols are bound to get him.”

The inspector nodded. “If he stays with the car, yes. But he may take to the open country again.”

“Wounded—and in this weather?”

The policeman spread his hands. “Who can tell what a desperate man will do?”

Solo stared thoughtfully at the wrecked car and then raised his eyes to the snow-covered fields and the wood beyond. He said, “I don’t get it. He’s back-tracking all the time. Why would he want to do that, unless…But that’s impossible.”

“We’re thinking the same thing,” Illya said. “Let’s get back to the Citroen. Goodbye, Inspector.”

The little car headed once more toward Silkeborg. Illya said, “It’s crazy, but it’s the only thing that makes sense. He’s trying to get back to the chalk mine. There’s nowhere else for him to go. We’ll drive to Jacobsen’s place and pick up reinforcements.”

Solo objected, “But you blasted the front of the mine in, and he can’t use the tunnel. What can he hope to gain?”

“There may be another way in that we don’t know about. That’s why we’ve got to see Jacobsen.”

They went into Silkeborg through Herningsvej and cut through the Town Square.

Illya laughed suddenly. “It’s a wonder Thrush didn’t make this place its headquarters,” he said. “Down the road there, in a street with no name, they make all the paper for the Danish banknotes. That could be handy.”

They met two more patrols before they got onto the road that led to Jacobsen’s farm, but neither had news of the wounded man.

“It looks like the inspector was right,” Solo said. The major’s trying to make it overland. If he’s headed this way.”

“I wish him joy,” said Illya. “Remember what happened to the Donners. And they had covered wagons.” They found Viggo working in the barn. He listened to their story skeptically.

“A man on foot would not get far in this country,” he said. “He had no coat, no hat, and you say he has a bullet in him. No, it is not possible.”

“But if he did,” Solo insisted, “and if he made it back to the mine—could he get back inside?”

“Another tunnel? Some secret entrance? Perhaps, but I do not know of one.”

“Well, there’s only one way to find out. We’ve got to go back there and watch for him.”

Viggo sighed gustily. “If you say so, my friend. But if he had the seven-league boots of the fairy tales, he could not have got there yet. So first we shall eat and drink. It will be cold waiting.”

They returned to the house. The imperturbable Else served them meatballs swimming in thick brown gravy, with beetroot and sugared potatoes. Solo got the idea that if a regiment marched unexpectedly into the farm she would dish up a meal with just as little fuss. She put bottles of lager beside the plates and poured a glass of akvavit for each man. “The weather is cold,” she explained in halting English. For her that was an oration.

It was half-past three when they set out for the mine, and the setting sun was reddening the sky. Leaden clouds were massed ominously, portending a further snowfall, but mercifully the wind had dropped to little more than a stiff, cutting breeze.

Neither human nor animal moved on the dead white waste around them as they plodded along the road. The great tumbled mounds of rock and earth that now completely blocked the mouth of the mine were covered by a deep carpet of snow that rounded and smoothed their outlines. Not a trace of a footprint broke the virgin surface of the hillside and its approaches.

“It looks peaceful enough,” Illya said, “but I suppose that if he’s around, he would hardly be likely to try to get in at the front door. Much as I hate the thought, I fear we shall have to do a little climbing.”

“There is nothing else for it,” Viggo agreed. “If there is another way into the mine, it must be on the far side of the slope. Or perhaps on the crest of the hill.” He looked at Solo questioningly. “We know this is where the roof-doors of the workshop must be. Could there not also be a smaller entrance—an inspection ladder, perhaps—beside them?”

Solo said, “It sounds feasible. But in these conditions finding it is going to be quite a trick. It had to be well camouflaged at the best of times. Now we might as well be looking for a grain of icing sugar in a ton of cotton wool.”

“True—but at least from the ridge we can keep better observation in case our friend is on his way.”

“And freeze to death sooner,” Illya said gloomily. He gave an exaggerated shudder, hunching his shoulders to bring the collar of his jacket higher around his ears. “Well, if we must, let’s get started. It will be dark in less than an hour.”

“We’ll split forces,” Solo decided. “Viggo, you and Illya work up the left. I’ll try to the right. We’ll rendezvous at the top and quarter the ground. It’s a poor chance, but it’s the only one we’ve got.”

They moved off.

The going was even tougher than they had expected. Their feet sank deep in the light, soft snow, often without finding firm hold beneath. They slithered, slipped, and sometimes fell full-length. A loose boulder on which Solo unwarily put his weight sent him skittering ten feet downward, clutching wildly at the yielding drifts.

Then the first shots came, cutting through the snow and sending a shower of rock splinters into his face. There was no cover. All he could do was lie still, fumbling with half-frozen fingers for the gun in his right-hand pocket.

Keeping his head low, he began to wriggle deeper into the snow, like a crab seeking shelter by burying himself in the sand.

Illya called anxiously, “Napoleon! Are you all right?”

“Ecstatic!” he shouted back. “I do this all the time.” Another burst of shots came from above, landing perilously close. Even in the rapidly failing light the hidden marksman was finding the range.