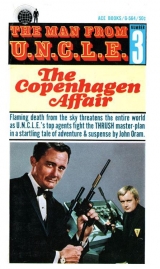

Текст книги "The Copenhagen Affair"

Автор книги: John Oram

Жанры:

Боевики

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 7 страниц)

COPENHAGEN WAS THE BEGINNING…

Strange aircraft had been reported in the skies over Denmark—immense and spherical, capable of flying vertically as well as horizontally, and at such high velocities that they were gone almost before they could be spotted by observers.

Flying saucers? Perhaps—but flying saucers developed and controlled by THRUSH!

Their purpose? The purpose of THRUSH itself—to subdue and rule all the world’s nations.

THE ENDING COULD ONLY BE DESTRUCTION…

PROLOGUE

THERE IS A row of buildings in New York City, a few blocks from the United Nations Building. It consists, starting from the south end, of a three-storied whitestone which appears fairly new in contrast with the series of brownstones which make up most of the row, and at the north end a busy public garage. The brownstones are occupied by a few lower-income families living above the decrepit shops and business premises at street level. Del Floria’s tailor shop occupies the street level space in a brownstone near the middle of the block. The first and second floors of the whitestone are taken up by an exclusive “key club” restaurant named The Mask Club, which features fine food served by waitresses wearing masks (and very little else) to patrons who don masks covering nostrils to brow as they enter.

On the third floor of the whitestone is a sedate suite of offices, the entrance to which bears the engraved letters U.N.C.L.E. And in this suite of offices a rather ordinary group of people handle mail, meet and do business with visitors, and in general give the impression of some normal organization engaged in a special charity project or a fund foundation headquarters.

All these buildings are owned by U.N.C.L.E. All the people involved in the activities of the garage and the key club are in the employ of U.N.C.L.E.; many of the patrons of The Mask Club are affiliated with U.N.C.L.E.; and even the frowsy tenants of the brownstones, including old Del Floria, the tailor, are members of the organization.

Behind the outer, crumbling skin of the four old brownstone buildings in the middle of the row is one large edifice comprising three floors of a modern, complex office building…a steel maze of corridors and suites containing brisk, alert young people of many races, creeds, colors and national origins…as well as complex masses of modem machinery for business and communications.

There are no staircases. Four elevators handle traffic vertically. Below basement level an underground channel has been cut through from the East River, and several cruisers (the largest sixty feet long) are bobbing at the underground wharf beneath the brownstone complex. If you could ascend to the roof and examine the huge neon advertising sign there, you might detect that its supporting pillars concealed a high-powered shortwave aerial and elaborate electronic receiving and transmitting equipment.

This is the heart, brain and body of the organization known as U.N.C.L.E. (United Network Command for Law and Enforcement). Its staff is multinational. Its work crosses national boundaries with such nonchalance that a daily short-wave message from the remote Himalayas fails to flutter any eyebrows—even though there is no recorded wireless station in the Himalayan area according to the printed international codebooks.

The range of problems tackled by U.N.C.L.E. is immense and catholic. There usually will be a sense of something international in the wind. But just as some of the smaller nations call on the United Nations organization for certain domestic problems beyond their own abilities (usually problems of a humanitarian, medical or technical nature), so U.N.C.L.E. may find itself called into local situations.

Anything which might affect large masses of people, or which might set up a general reaction affecting several countries or several forces, is a job for U.N.C.L.E. It could be the attempt by an organization to cause the accidental firing of a missile from the territory of one friendly power into another in order to create complications within the alliance. It could be the wanderings of a tube of germ bacilli “lost” from an experimental station. It could be an attempt to manipulate the currency of a nation.

Whatever the situation is certain that from his office on the third floor of the brownstone enclave a shabby, gray-haired man will send one or more of his tough young men and women to cope before all hell breaks loose. He will not hesitate to send them into terrible danger against seemingly impossible odds. If an agent is lost, his one concern will be who is to be sent to replace the casualty and salvage the operation.

And the man who so often draws the short straw is Napoleon Solo, Chief Enforcement Agent for U.N C.L.E.

CHAPTER ONE

SOMEHOW, NEAR CHRISTMAS, even the sleek SAS Convair Coronado 990, fastest airliner in the world, seems to take on some of the season’s magic.

Cheerful Danish expatriates, arms laden with bright-wrapped packages, crowd aboard, heading home from London for the Juleaften feast. There’s an extra-welcoming smile on the face of the pretty stewardess and an extra warmth in the cabin after the raw air on the tarmac. Nobody would be much surprised if Santa himself came beaming through the pilot’s hatch to greet the hundred passengers.

Christmas spirit? If you are not on the best of terms with your next-seat neighbor by the time you have eaten your smorrebrod and drunk your first glass of Tuborg you must be a Scrooge indeed. The Danes are always friendly, but there’s something about a December flight that breaks down the last barriers.

Mike Stanning hoped the girl beside him would get the message.

He had noticed her first in the departure lounge at the airport. She had been sitting alone—a slim, trim figure in neat, expensive tweeds. She wore no hat. Black, shoulder-length hair framed her oval face like a glossy helmet The hand turning and returning the untasted glass on the table before her was brown, well-shaped, with long, sensitive fingers. When she had stood up at the loudspeaker’s summons Mike had seen that she was not more than five feet two but built with the grace of a ballet dancer. He’d taken particular pains to get the seat beside her in the aircraft.

As soon as they had unfastened their seat belts he offered her a cigarette. She shook her head.

He tried her with his inexpert Danish. She said, I’m sorry. I don’t understand.” Her voice was low and musical.

Mike said, “Don’t worry. The Danes don’t understand it, either. But I’m working on it. This is your first time for Copenhagen?”

“Yes.”

“Visiting friends?”

“Not exactly.”

“Business?” Mike tried again. “I’m in engineering, myself. Salesman, you know. Boost the exports, and all that jazz.”

“Yes,” she said slowly. “I suppose you could say I was on business.” There was a curious expression in her brown eyes. Her tone forbade further questioning. She took up a magazine and began to read.

Mike called the stewardess and ordered a large Scotch. The girl refused a drink. Through the rest of the hour-long flight he tried to interest himself in a paperback novel.

Mike always enjoyed the moment of arrival at Kastrup, surely the friendliest airport anywhere—the waving and smiling of the “reception committees” beyond the barrier as the passengers filed through passport inspection; the hugging and hand-shaking, the kissing and laughter (and not a few tears) as families were reunited. There was nobody to meet the girl, he noticed. Carrying only a sling-bag of the type they sell in airport gift shops, she pushed quickly through the crowd around the barrier. She did not reappear on the bus for the short trip to the city terminal. Sharing vicariously the excitement around him, Mike forgot about her. He walked out into the bustle of Vesterbrogade, Copenhagen’s main street, with a sense of homecoming.

He checked in at the Excelsior on the corner of Colbjornsensgade, a modest hotel where the food is excellent even by Copenhagen’s exacting standards and the rooms both comfortable and quiet.

“You will be with us for Christmas, Mr. Stanning?” the desk clerk asked.

“No, worse luck. I’ll make it someday, but this time it’s just a quick trip. I have to be in London in three days’ time.”

“A pity,” the clerk smiled. “There is so little to do here out of season.”

“Oh, I don’t know,” Mike said. “You can usually find a little action around if you care to look for it.”

That turned out to be the understatement of his life.

It was while walking through Stroget late the following afternoon that he saw the girl again.

You won’t find Stroget on any Copenhagen street map. It is not one street, but five—Ostergade, Amagertorv, Vimmelskatet, Nygade and Frederiksberggade—winding from Kongens Nytorv to the Town Hall Square, where in December the seventy-foot Christmas tree from Crib Skov towers like the presiding genius of the festival.

Think of Piccadilly, Bond Street and Fifth Avenue rolled into one. That’s Stroget. You can buy anything along its winding length: furs, trinkets, porcelain, gold and silver, furniture, pictures, antiques, or just a simple toy for a couple of kroner. And in December the sellers of Christmas trees and the Jul straw goats are out in force on the sidewalks, their colorful stalls adding to the general gaiety.

There is no traffic problem in Stroget. It has long been closed to all traffic on wheels except baby carriages. So you can stroll along at leisure, crossing from side to side of the street without risk to life or limb. Oddly, this security takes some getting used to. You can always pick out an Englishman or an American by the way he stays grimly on the sidewalk while the Danes parade happily along the middle of the road.

The girl was no exception. She was walking slowly, stopping every now and then to look at the superb window displays.

“Good evening,” Mike greeted her. “Just sightseeing, or is there something you want to buy? I know all the right places.”

She smiled up at him. “I’m just idling,” she admitted, “and I was getting a little bored with my own company. Would you like to buy me a coffee somewhere?”

“I’ll do better,” Mike said. “Ever tasted Yule punch? No? Then your education is going to start right now. It’s a hot, spiced nectar that every good Dane drinks at Christmas, and I know a little bar that’s got the recipe dead to rights.” He grinned. “By the way, do you realize I don’t even know your name?”

“I’m sorry. It’s Bland. Norah Bland.”

“Nice! And I’m Stanning. Mike Stanning. Like the song says: Lovely to know you.”

The next few hours were to live long in Mike’s memory.

They were lingering over coffee after a long, late dinner in the Japanese room at The Seven Nations when Norah said suddenly, “Will you take me to a place called The Linden Tree?”

He looked at her, astonished. “The Linden? I thought you said you didn’t know Copenhagen.”

“I don’t.”

“Then how do you know about the Linden? It’s not the sort of joint that attracts the tourist trade.”

“It doesn’t matter how I know. I just want to go there—now.”

He sighed. “Sweetheart,” he said, “it’s time you heard some of the facts of life. The Linden is a rough: tough joint in the heart of Nyhavn, and Nyhavn is the roughest, toughest part of Copenhagen. It’s the seamen’s quarter, and at this time of night—in case you’re not aware of the fact, it’s pushing midnight—it’s liable to be really jumping. Not that the Linden is a spot for well-brought up young women at any time of day. So let’s forget it. We’ll go to Vingaarden and hear some good jazz.”

She said: “Please, Mike—the Linden Tree. Now.”

He signaled to the waiter. “All right, if you’re set on it. But don’t blame me if you get your bag snatched—or,” he added thoughtfully, “if I get my skull cracked and you have to walk home.”

The glaring neons over the bars along Nyhavn were reflected in the black water of the harbor like blood. A party of carousing Swedes stumbled unsteadily along the sidewalk, arguing loudly. Somewhere away in the shadows a woman was shouting a stream of drunken abuse. As Mike paid off the taxi a sudden gust of cold wind made Norah shiver and pull her coat closer around her.

Mike said, “You’re sure you want to go through with it?”

“Yes.”

“All right. Then stick close. The boys may get wrong ideas.”

He pushed open the swinging doors of The Linden Tree and led the way down a flight of uncarpeted stairs. At the bottom a man sat wedged between the wall and a small table. His waistline must have been all of sixty inches and his moon face fell to his shabby shirt collar in a succession of flabby wattles. He tore two paper tickets from a roll and wheezed, “Four kroner.”

Norah said, “Let me pay, Mike. You’ve been shelling out for everything so far.”

In her haste to forestall him her finger slipped and her handbag fell to the floor. Lipstick, compact, and the dozen and one things women carry burst out like a shower. Mike knelt to retrieve them. “That Yule punch!” he said. “I warned you it was potent.”

They were turning from the table when the fat man called, “Miss, I think you forget something.” He held out a small, flat packet.

“Oh! Thanks,” Norah said. “I thought we had picked up everything. You’re very kind.”

He grunted “Velkom!” uninterestedly and returned to his study of the evening paper.

They went on into the club. Surprisingly, it was half empty. Four seamen stood talking over their drinks at the small bar counter. A few couples were dancing to the music of a three-piece combo. In a far corner of the long room a boy and girl who looked like students were being uninhibitedly romantic.

Mike chose a table. A waiter came over and lit the inevitable candle of welcome. Mike ordered two lagers.

Norah looked around. “I thought you said this was a rough place,” she said. “It looks pretty harmless to me.”

“It warms up,” he told her. “It’s still fairly early for Nyhavn.”

A girl came into the room alone. She wore a black, high-necked sweater and tight black trousers. She was tall and thin, with a pale face that looked undernourished. Her thick hair was blazing red. She walked across to their table and put a hand tentatively on the back of a chair. “May I sit?”

“Help yourself,” Mike said. “Would you like a drink?”

“Thank you, no. I buy my own.”

She fumbled in a shabby purse and produced three kroner. Without being told, the waiter brought her a Carlsberg. She poured it expertly in the Danish fashion, dropping the beer almost vertically into the glass. She raised the glass, nodded, stared at them with vivid blue eyes, said “Skaal!” then nodded again and drank.

After a few minutes she got up and went over to join the seamen at the bar. Curiously, Mike could have sworn that she gave Norah a glance of understanding as she left the table.

“Want to dance?” Mike suggested.

Norah shook her head. “No,” she said. “You were right. This place bores me, and I think I’m tired. Would you mind taking me home?”

“Of course. The only thing is, I don’t know where you live.”

“I’ve got an apartment in Marievej, out in Hellerup. A—a friend lent it to me.”

He said nothing, and she smiled. “That’s what I like about you, Mike,” she said. “You’re not the inquisitive type.”

Suddenly, in the taxi, she was in his arms. She kissed him almost desperately. “We have so little time,” she whispered.

He could feel wetness on his cheek and knew she was crying. He said awkwardly, trying to make light of it, “Oh, come on, now. We’ve got a couple of days together yet. There’s nothing to get upset about.”

She drew away. “You don’t understand. How could you?”

He said, “I’m beginning to understand that you’re in some kind of trouble. What is it? The law?”

“No.” She seemed to make up her mind. “Mike, I’ve got to trust you. Please keep this with you until you get back to London. I’ll contact you there—at your office.”

She opened her bag and brought out the small oblong package the doorman at The Linden Tree had given her. In the intermittent light of the street lights he could see that it was wrapped in white paper and that the ends were sealed with wax.

He grinned. “What is it? Purple hearts?”

Her voice was somber. “It’s dynamite.”

“As long as it doesn’t blow up on me, I’ll look after it,” he answered, stuffing the package in his pocket. Then he took her in his arms again.

CHAPTER TWO

A BUSINESS DEAL kept Mike occupied throughout the morning of the next day. It was past 1:00 P.M. when he returned to the hotel for lunch.

The desk clerk handed him a written message: “Please ring Trorod 53945.”

He looked at it, puzzled. Trorod was the exchange for Holte, a village some miles outside Copenhagen. He knew no one there. He went to his room and called the number.

A cultivated voice answered. It said, “Garbridge here.”

That rang no bell. Mike said, “Stanning. You want me?”

“Ah, yes, Mr. Stanning.” The voice was almost purring. “My name is Garbridge…Major Garbridge. We haven’t met, but I have a little proposition which I think would interest you. Could you come out here? I’m at the Rodehus, Gammel Holte, you know.”

“When?” Mike asked.

“At once, if you can spare the time. It would be worth your while.”

Mike looked at his watch. “I could be with you at about four o’clock. But I’m not sure of the way.”

Garbridge said, “Take the S-Train to Jaegersborg, and get the silver bus there. The driver will drop you off on the main road near the house, and I’ll be waiting for you.”

“Fine,” Mike said. “I’m on my way.”

The journey was shorter than he had anticipated. It was still broad daylight when the bus deposited him in what appeared to be a completely deserted stretch of countryside. The road was flanked by flat pastures where red cattle grazed amicably, and beyond, forests of beech. There was not a house in sight. It was with some relief that Mike saw a tall figure striding toward him.

Garbridge was a man of about fifty, maybe a little on the wrong side. He had a good jaw, a thickish nose, and eyes that did things to Mike’s spine. They were clear amber, cold as death and just as impersonal. The lashes that fringed them were snow white.

He wore nicely shabby gray tweeds and a regimental tie. The sandblasted brier looked like a permanent fixture in his mouth. His shoulders were wide and square. Given a tin hat and a pair of binoculars he would have been a natural for a trench coat ad. Mike wondered what he was doing in the wilds of Seeland.

His voice was curiously gentle.

“I had a feeling you had overestimated the time,” he greeted Mike cheerily. “Well, that’s all to the good. Gives us more time to chat, what?”

A few minutes’ walk brought them to a side road which led straight toward the beech forest. They strode along a path through the great trees and came suddenly to a pair of massive wrought-iron gates, beyond which a drive wound through banks of well-kept shrubs. The bushes gave Mike a hemmed-in feeling. The light had taken on a greenish tinge and there was a dank taste of rotting leaves in the air. After awhile they came out into the open again. Around and about them was a stretch of park land fringed with trees,. and right ahead was the Rodehus. The major stopped to let Mike catch his breath and admire the place.

It was a low, rambling house built in the traditional Danish L-shape but looking as if successive generations had kept adding a shingle here and there and tacking on another room for the unexpected guest. The walls were pink-washed and the windows were flanked by open shutters in a deeper red that matched the roof tiles. A Rolls Royce could have been driven through the main doors without scratching the paintwork. A velvet lawn swept down to meet the parkland.

They went in by the main entrance and found themselves in a large square hall with a black and white stone flagged floor like a checkerboard. Logs were burning in a fireplace large enough to roast an ox. The flames danced on suits of armor and the trophies of arms which decorated the walls. A broad staircase carpeted in purple led up to the first floor and at its head there was a life-size oil painting of a woman in Elizabethan dress. It was all more like an English castle than a Danish country manor.

“Here we are,” said the major. “And before we get down to business I think a drink is indicated. Come into the library.”

The library was darker than the hall. There was a nice smell of old leather and good tobacco. The main furnishings were easy chairs, a long chesterfield and a massive table-desk. Books covered most of the walls and the rest of the space was occupied by sporting prints.

“Make yourself comfortable,” said the major, indicating the chesterfield drawn up to the fire. He pressed the bell and a second or two later a thickset, surly man appeared in the doorway. He was dressed like a butler but he had ex-pug written all over his cauliflower ears and battered nose. His hands matched his face, with the knuckles pushed back halfway up his wrists.

“You rang, sir?”

“Whisky, Charles,” said the major.

“I don’t want to be awkward,” Mike said, “but if it’s all the same to you I’ll take beer. It’s a bit early for the hard stuff.”

“Very wise,” the major agreed. “Bring some lager, Charles.”

The butler brought the drinks, set them on a table and went out, closing the door carefully behind him.

The major poured himself almost half a tumbler of straight Scotch, said “Cheers!” and tossed it down without a blink. He refilled the glass and stood with his back to the fire, looking at Mike thoughtfully.

Suddenly he said, “And now—touching on Norah Bland…”

Mike was so surprised that he almost dropped his beer. To gain time he took a long drink.

Then he repeated slowly, “Bland? Norah Bland? Should I know her?”

“You should,” the major said. “She is a beautiful girl, and you spent a great deal of last night with her.” He was smiling coldly. The affable squire manner had dropped from him and his yellow eyes were like agates.

Mike sighed. “Nothing like that ever happens to me. You must be thinking of two other people…”

The major shook his head, still smiling thinly. it won’t do, Stanning. Let me refresh your memory. You met Miss Bland on the plane from London. You met her again yesterday afternoon and the two of you were together until early this morning. You took her to dinner at The Seven Nations and then for a drink at The Linden Tree—”

Mike said, “Just supposing you happen to be right, which I don’t admit, what in hell has it got to do with you?”

He shrugged. “I thought you ought to know that she is dead.”

Something cold clutched at Mike’s insides. He remembered honest brown eyes under curled lashes, heard the soft voice saying, “We have so little time.” He forgot his act and muttered stupidly, “Norah…dead?…How?”

The major drank again, watching him. At last he said: “After she left you she was in…an accident.”

“I don’t believe it. It’s impossible.”

He spread his hands. “That’s how it goes, old man…” He walked over to the desk and unlocked a drawer. “Somebody always draws the last card.” He opened the drawer and rested his hand inside. “But before she died,” he continued more slowly, “she handed you a sealed packet.”

“So?”

His hand came up fast, gripping a 9mm Luger pistol. “So I want it,” he snapped.

The sight of the gun acted like a cold shower. Mike came out of his trance.

“Put that thing away,” he said. “It doesn’t scare me. I’m damned if I know what you’re talking about, anyway. Norah gave me no packet.”

“She gave it to you—sometime during the night. Hand it over quickly, please.”

Mike kept his eyes on the gun pointed unwaveringly at his middle. He said, “Don’t be childish. Suppose you squirt that thing—how do you expect to get away with it? The hotel clerk and the switchboard girl know you phoned me this morning, and I left your number with the desk when I started out. Even a country copper couldn’t fail to add it up if I disappear.”

“You’re not going to disappear,” said the major. “I was explaining the mechanism of the pistol to you and forgot the shell in the chamber. Don’t you ever read the inquest reports? I can only hope that in your case the necessity for such an interesting ceremony will not arise.”

Mike forced a grin. “You’ve got it all figured out, but it won’t get you anyplace. The package is tucked away safely, miles from here.”

“You underrate my intelligence. You were followed all morning and your room was searched as soon as you had left to come here. The package is not there, and since you have not been near a post office you must have it with you. For the last time, hand it over.”

Mike picked up his glass of beer. “You’ve been seeing too many movies and they’ve gone to your head. For some reason you saw fit to put a tail on Norah and me and you seem to be pretty well acquainted with our movements. But about the packet you’re all wet. Well, if it amuses you, all right. But you’ve played cops and robbers with me long enough. Now I’ll tell you what I’m going to do. I’m going to finish this drink and then I’m going to walk out of here. And if I’ve got the packet—as you seem to think—it goes out with me…”

He raised the glass and drank. His nonchalance would have delighted a charm-school instructress. It had the reverse effect on the major. He swung from behind the desk and came at him, the gun stuck out threateningly.

That was what Mike had played for. As Garbridge came within range he jerked the glass straight into his face. The major’s right hand went up instinctively, and in the same instant Mike kicked him right where it would do the most good. Garbridge screamed, dropped the Luger and fell to the carpet, moaning. His face was grayer than his hair. In his football days Mike had been known as a useful place-kicker. And he wanted that gun.

Footsteps pounded across the hall and Charles crashed through the door. He looked down at his boss and cursed.

Mike beckoned him with the Luger. “Get those hands up and stand by the wall,” he ordered. “Now listen:

“I’m a peaceful kind of guy, and when a man invites me to have a drink I don’t expect him to pump lead into me by way of an appetizer. It upsets my digestion, and when that happens I tend to get more than a little restive. I will be glad if you will explain that to the major when he is in a mood to listen.

“You can tell him, too, that something stinks around this joint. I don’t know what it is, but I intend to find out.”

Charles scowled.

“Fine!” Mike scowled back, just to show him he had no monopoly. “One last point. Your boss tells me a friend of mine died today. It occurs to me that maybe she was murdered.” The butler’s piggy eyes flickered. “It occurs to me further,” Mike went on, “that you may have had a hand in it. If that proves to be the case I want you to know that I intend to blast hell out of you with nice filed bullets out of this self-same gun. You’ll need a bathtub to plug the hole.”

“So ’elp me God…”

“I hope so,” Mike agreed piously. “Meanwhile, turn your face to the wall.”

Charles shuffled around apprehensively and Mike brought the barrel of the Luger sharply down on his skull. He crumpled without a murmur.

Mike tucked the gun into the waistband of his trousers, went into the hall and locked the library door on the outside.

He was not frightened but he was far from happy. He could see that as soon as he left the Rodehus he was in a spot. He had ruined the major for horseback riding for quite some time and assaulted his butler with a lethal weapon for which he had no permit. Garbridge had only to telephone the local police and Mike would have plenty of explaining to do. He could not imagine any rural policeman swallowing the story he had to tell, and he had no witnesses.

On top of mayhem and battery and carrying concealed weapons he still had that package, which might contain anything from heroin to a package of safety pins. Judging from the major’s anxiety to get his fingers on it, he did not think it would turn out to be the latter. He listened. There was no sign of movement in the house. If the major had other servants they had obviously been trained to mind their own business. He took out the girl’s parting gift, broke the seals and tore off the paper, revealing a plain brown cardboard box and a folded note.

He looked in the box first. All it contained was an unopened pack of Danish cigarettes. He tipped it into his palm and examined it closely. It was a standard brand and the cellophane wrapper was intact. He swore softly and turned his attention to the note.

That gave him another shock. It was from Norah Bland and it was addressed to him.

Mike,

If you read this it means that I haven’t shown up to collect the enclosed which, when we get out of here, I’m going to ask you to hold for me. Don’t fool with the cigarettes. Take them personally to U.N.C.L.E. offices, New York—and don’t let a soul know you have them. If you’re broke, borrow transportation. But for God’s sake don’t lose a minute. Get going, Mike. And good luck.

Mike’s eyes were giving him trouble by the time he had finished reading. It began to look as if Norah had anticipated becoming a casualty. He remembered the sadness that had been in her eyes even while he had held her close in the taxi.

He wondered when she had found time to write the note. He was fairly certain the doorman in the Linden Tree had slipped the package to her. Then he remembered that before leaving the club she had gone to powder her nose and had taken more time than had seemed necessary.

He stood for a minute, holding the note and thinking. Then he stuffed note and box back into his pocket, listened briefly for sounds beyond the library door, and made for the main exit.

Darkness had fallen and he knew he would have considerable difficulty in finding his way back to the highway. He cut diagonally across the lawn and onto the shrub-lined lower drive. It was comparatively easy going there. The problem would be to find the path that led through the beech wood. He wished he had a pocket flashlight

The entrance gates were still open. As he passed through them he heard voices, and, turning briefly, he saw lights somewhere on the park land. Evidently the major had recovered from his indisposition.