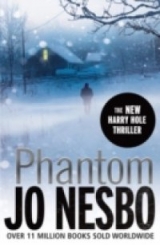

Текст книги "Phantom"

Автор книги: Jo Nesbo

Соавторы: Jo Nesbo,Jo Nesbo

Жанр:

Триллеры

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 13 (всего у книги 28 страниц)

19

It took two months from the meeting between the old boy and Isabelle for the clean-up to begin.

The first ones to be busted were the Vietnamese. The newspapers said the cops had struck in nine places simultaneously, found five heroin stores and arrested thirty-six Vietcong. The week after it was the Kosovar Albanians’ turn. The cops used elite Delta troops to raid a flat in Helsfyr which the gypsy chief thought no one knew about. Then it was the turn of the North Africans and Lithuanians. The guy who was head of Orgkrim, a good-looking model-type with long eyelashes, said in the papers they had been given anonymous tip-offs. Over the next few weeks street sellers, everything from coal-black Somalis to milky-white Norwegians, were busted and banged up. But not a single one of us wearing an Arsenal shirt. It was already clear that we had more elbow room and the queues were getting longer. The old boy was recruiting some of the unemployed street sellers, but keeping his end of the bargain: heroin dealing had become less visible in Oslo city centre. We cut down on heroin imports as we earned so much more on violin. Violin was expensive, so some tried to switch to morphine, but they soon came back.

We were selling faster than Ibsen could make it.

One Tuesday we ran out at half past twelve, and since it was strictly forbidden to use mobiles – the old boy thought Oslo was fricking Baltimore – I went down to the station and rang the Russian Gresso phone from one of the call boxes. Andrey said he was busy, but he would see what he could do. Oleg, Irene and I sat on the steps in Skippergata waving away punters and chilling. An hour later I saw a figure come limping towards us. It was Ibsen in person. He was furious. Yelling and cursing. Until he caught sight of Irene. Then it was as if the storm was over and his tone became more conciliatory. Followed us to the backyard where he handed over a plastic bag containing a hundred packages.

‘Twenty thousand,’ he said, holding out his paw. ‘This is cash on delivery.’ I took him aside and said that next time we ran out we could go to his place.

‘I don’t want visitors,’ he said.

‘I might pay more than two hundred a bag,’ I said.

He eyed me with suspicion. ‘Are you planning to start up on your own? What would your boss say to that?’

‘This is between you and me,’ I said. ‘We’re talking chicken-feed. Ten to twenty bags for friends and acquaintances.’

He burst out laughing.

‘I’ll bring the girl,’ I said. ‘Her name’s Irene, by the way.’

He stopped laughing. Looked at me. Club Foot tried to laugh again, but couldn’t. And now everything was written in big letters in his eyes. Loneliness. Greed. Hatred. And desire. Fricking desire.

‘Friday evening,’ he said. ‘At eight. Does she drink gin?’

I nodded. From now on she did.

He gave me the address.

Two days later the old boy invited me to lunch. For a second I thought Ibsen had grassed on me, because I could remember his expression. We were served by Peter and sat at the long table in the cold dining room while the old boy told me he had cut out heroin imports across the country and from Amsterdam and now only imported from Bangkok via a couple of pilots. He talked about the figures, checked I understood and repeated the usual question: was I keeping away from violin? He sat there in the semi-gloom gazing at me, then he called Peter and told him to drive me home. In the car I considered asking Peter whether the old boy was impotent.

Ibsen lived in a typical bachelor pad in a block on Ekeberg. Big plasma screen, little fridge and nothing on the walls. He poured us a cheap gin with lifeless tonic, without a slice of lemon, but with three ice cubes. Irene watched the performance. Smiled, was sweet, and left the talking to me. Ibsen sat with an idiotic grin on his face gawping at Irene, though he did manage to close his gob whenever saliva threatened to leak out. He played fricking classical music. I got my packages and we agreed I would drop by again in a fortnight. With Irene.

Then came the first report about the falling number of ODs. What they didn’t write was that first-time users of violin, after only a few weeks, were queueing with staring eyes and visible fits of the shakes from withdrawal symptoms. And as they stood there with their crinkled hundred-krone notes and found out that the price had gone up again, they cried.

After the third visit to Ibsen he took me aside and said that next time he wanted Irene to come alone. I said that was fine, but then I wanted fifty packages and the price was a hundred kroner apiece. He nodded.

Persuading Irene required some effort, and for once the old tricks didn’t work. I had to be hard. Explain this was my chance. Our chance. Ask if she wanted to stay sleeping on a mattress in a rehearsal room. And in the end she mumbled that she didn’t. But she didn’t want to… And I said she didn’t have to, she should just be nice to the lonely old man, he probably didn’t have much fun with that foot of his. She nodded and said I had to promise not to tell Oleg. After she left for Ibsen’s pad I felt so down I diluted a bag of violin and smoked what was left in a cigarette. I woke up to someone shaking me. She stood over my mattress crying so much the tears were running down onto my face and making my eyes sting. Ibsen had tried it on, but she had managed to get away.

‘Did you get the packages?’ I asked.

That was obviously the wrong question. She broke down completely. So I said I had something to make everything alright again. I fixed up a syringe and she stared at me with big, wet eyes as I found a blue vein in her fine, white skin and inserted the needle. I felt the spasms transplant themselves from her body to mine as I pressed the plunger. Her mouth opened in a silent orgasm. Then the ecstasy drew a bright curtain in front of her eyes.

Ibsen might be a dirty old man, but he knew his chemistry.

I also knew that I had lost Irene. I could see it in her face when I asked about the packages. It could never be the same. That night I saw Irene glide into blissful oblivion along with my chances of becoming a millionaire.

The old boy continued to make millions. Yet still he wanted more, faster. It was as if there was something he had to catch, a debt that was due soon. He didn’t seem to need the money; the house was the same, the limousine was washed but not changed and the staff remained at two: Andrey and Peter. We still had one competitor – Los Lobos – and they too had extended their street-selling operations. They hired the Vietnamese and Moroccans who were not already banged up, and they sold violin not only in the town centre but also at Kongsvinger, in Tromso, Trondheim and – so the rumour went – in Helsinki. Odin and Los Lobos may have earned more than the old boy, but the two of them shared this market, there were no fights for territory, they were both getting very rich. Any businessman with his brain fully connected would have been happy with the status fricking quo.

There were just two clouds in the bright blue sky.

One was the undercover cop with the stupid hat. We knew the police had been told that the Arsenal shirts were not a priority target for the moment, but Beret Man was snouting around anyway. The other was that Los Lobos had started selling violin in Lillestrom and Drammen at a cheaper price than in Oslo, which meant some punters were catching the train there.

One day I was summoned by the old boy and told to take a message to a policeman. His name was Truls Berntsen, and it had to be done with discretion. I asked why he couldn’t use Andrey or Peter, but the old boy explained that he didn’t want to have any contact that might lead the police back to him. It was one of his principles. And even if I had information that could expose him I was the only person beside Peter and Andrey he trusted. Yes, in many ways he did trust me. The Dope Baron trusts the Thief, I thought.

The message was that he had arranged a meeting with Odin to discuss Lillestrom and Drammen. They would meet at McDonald’s in Kirkeveien, Majorstuen, on Thursday evening at seven. They had booked the whole of the first floor for a private children’s party. I could visualise it, balloons, streamers, paper hats and a fricking clown. Whose face froze when he saw the birthday guests: beefy bikers with murder in their eyes and studs on their knuckles, two and a half metres of Cossack concrete, and Odin and the old boy trying to stare each other to death over the pommes frites.

Truls Berntsen lived alone in a block of flats in Manglerud, but when I called round early one Sunday morning, no one was at home. The neighbour, who’d obviously heard Berntsen’s bell ring, stuck his head out from the veranda and shouted that Truls was at Mikael’s, building a terrace. And while I was on my way to the address he had given me I was thinking that Manglerud had to be a terrible place. Everyone clearly knew everyone.

I had been to Hoyenhall before. This is Manglerud’s Beverly Hills. Vast detached houses with a view over Kv?rnerdalen, the centre and Holmenkollen. I stood in the road looking down over the half-finished skeleton of a house. In front were some guys with their shirts off, can of beer in hand, laughing and pointing to the formwork which was obviously going to be the terrace. I immediately recognised one of them. The good-looking model-type with long eyelashes. The new head of Orgkrim. The men stopped talking as they caught sight of me. And I knew why. They were police officers, every single one of them, who smelt a bandit. Tricky situation. I hadn’t asked the old boy, but the thought had struck me that Truls Berntsen was the alliance in the police he had advised Isabelle Skoyen to form.

‘Yes?’ said the man with the eyelashes. He was in very good shape as well. Abs like cobblestones. I still had the opportunity to back away and visit Berntsen later in the day. So I don’t quite know why I did what I did.

‘I have a message for Truls Berntsen,’ I said, loud and clear.

The others turned to a man who had put his beer down and waggled over on bow legs. He didn’t stop until he was so close to me that the others couldn’t hear us. He had blond hair, a powerful, prognathous jaw that hung like a tilting drawer. Hate-filled suspicion shone from the small piggy eyes. If he had been a domestic pet he would have been put down on purely aesthetic grounds.

‘I don’t know who you are,’ he whispered, ‘but I can guess, and I don’t want any fucking visits of this kind. OK?’

‘OK.’

‘Quick, out with it.’

I told him about the meeting and the time. And that Odin had warned he would be turning up with his whole gang.

‘He daren’t do anything else,’ Berntsen said and grunted.

‘We have information that he’s just received a huge supply of horse,’ I said. The guys on the terrace had resumed their beer-drinking, but I could see the Orgkrim boss casting glances at us. I spoke in a low voice and concentrated on passing on every detail. ‘It’s stored in the club at Alnabru, but will be shipping out in a couple of days.’

‘Sounds like a few arrests followed by a little raid.’ Berntsen grunted again, and it was only then I realised it was meant to be laughter.

‘That’s all,’ I said, turning to go.

I had only gone a few metres down the road when I heard someone shout. I didn’t need to turn to know who it was. I had seen it in his gaze at once. This is after all my speciality. He came up alongside, and I stopped.

‘Who are you?’ he asked.

‘Gusto.’ I stroked the hair out of my eyes so that he could see them better. ‘And you?’

For a second he regarded me with surprise, as though it was a tough question. Then he answered with a little smile: ‘Mikael.’

‘Hi, Mikael. Where do you train?’

He coughed. ‘What are you doing here?’

‘What I said. Delivering a message to Truls. Could I have a swig of your beer?’

The strange, white stains on his face seemed to light up all of a sudden. His voice was taut with anger when he spoke again. ‘If you’ve done what you came to do I suggest you clear off.’

I met his glare. A furious glare. Mikael Bellman was so stunningly handsome that I felt like placing a hand on his chest. Feeling the sun-warmed sweaty skin under my fingertips. Feeling the muscles that would automatically tense in shock at my audacity. The nipple that hardened as I squeezed it between thumb and forefinger. The wonderful pain as he punched me to save his good name and reputation. Mikael Bellman. I felt the desire. My own fricking desire.

‘See you,’ I said.

The same night it struck me. How I would succeed in what I guess you never managed. For if you had, you wouldn’t have dumped me, would you. How I would become whole. How I would become human. How I would become a millionaire.

20

The sun glittered so intensely on the fjord that Harry had to squint through his ladies’ sunglasses.

Oslo was not only having a facelift in Bjorvika, it was also having a silicone tit of a new district stuck out into the fjord where once it had been flat-chested and boring. The silicone wonder was called Tjuvholmen and looked expensive. Expensive apartments with expensive fjord views, expensive boat moorings, expensive bijou shops with exclusive items, art galleries with parquet flooring from jungles you had never heard of, galleries which are more spectacular than the art on the walls. The nipple on the most prominent edge of the fjord was a restaurant with the kind of prices that had caused Oslo to overtake Tokyo as the most expensive city in the world.

Harry went in and a friendly head waiter greeted him.

‘I’m looking for Isabelle Skoyen,’ Harry said, scanning the room. It seemed to be packed to the rafters.

‘Do you know what name the table’s reserved under?’ the waiter asked with a little smile that told Harry all the tables had been booked weeks ago.

The woman who had answered when Harry rang the Social Services Committee office in City Hall had at first been willing to tell him only that Isabelle Skoyen was out having lunch. But when Harry had said that was why he was ringing, he was sitting at the Continental waiting for her, the secretary had in her horror blurted out that the lunch was at Sjomagasinet!

‘No,’ Harry said. ‘Is it alright if I go and have a look?’

The waiter hesitated. Studied the suit.

‘Don’t worry,’ Harry said. ‘I can see her.’

He strode past the waiter before the final judgement was passed.

He recognised the face and the pose from the pictures on the Net. She was leaning against the bar with her elbows on the counter, facing the dining room. Presumably she was waiting for someone but looked more as if she were appearing on stage. And when Harry looked at the men around the tables he understood she was probably doing both. Her coarse, almost masculine face was split into two by an axe-blade of a nose. Nevertheless, Isabelle Skoyen did have a kind of conventional attraction other women might call ‘elegance’. Her eyes were heavily made up, a constellation of stars round the cold, blue irises, which lent her a predatory, lupine look. For that reason her hair was a comical contrast: a blonde doll’s mane arranged in sweet garlands on either side of her manly face. But it was her body that made Isabelle Skoyen such an eye-catcher.

She was a towering figure, athletic, with broad shoulders and hips. The tight-fitting black trousers emphasised her big, muscular thighs. Harry decided that her breasts were bought, supported by an unusually clever bra or simply impressive. His Google search had revealed that she bred horses on a farm in Rygge; had been divorced twice, the last from a financier who had made a fortune four times and lost it three; had been a participant in national shooting competitions; was a blood donor, in trouble for having given a political colleague the boot because he ‘was such a wimp’; and she more than happily posed for photographers at film and theatre premieres. In short: a lot of woman for your money.

He moved into her field of vision, and halfway across the floor her stare still hadn’t relinquished him. Like someone who considers it their right to look. Harry went up to her, fully aware that he had at least a dozen pairs of eyes on his back.

‘You are Isabelle Skoyen,’ he said.

She looked as if she was about to give him short shrift, but changed her mind, angled her head. ‘That’s the thing about these overpriced Oslo restaurants, isn’t it? Everyone is someone. So…’ She dragged out the ‘o’ as her gaze took him in from top to toe. ‘Who are you?’

‘Harry Hole.’

‘There’s something familiar about you. Have you been on TV?’

‘Many years ago. Before this.’ He pointed to the scar on his face.

‘Oh yes, you’re the policeman who caught the serial killer, aren’t you?’

There were two ways to play this. Harry chose to be direct.

‘I was.’

‘And what do you do now?’ she asked without interest, her gaze wandering over his shoulder, to the exit. Pressed her red lips together and widened her eyes a couple of times. Warm-up. Must be an important lunch.

‘Clothes and shoes,’ Harry said.

‘I can see. Cool suit.’

‘Cool boots. Rick Owens?’

She looked at him, apparently rediscovering him. Was about to say something, but her glance caught a movement behind him. ‘My lunch date’s here. See you again perhaps, Harry.’

‘Mm. I had hoped we might have a chat now.’

She laughed and leaned forward. ‘I like the move, Harry. But it’s twelve o’clock, I’m as sober as a judge and I already have a lunch date. Have a nice day.’

She walked away on her click-clacking heels.

‘Was Gusto Hanssen your lover?’

Harry said it in a low tone, and Isabelle Skoyen was already three metres away. Nevertheless, she stiffened, as if she had found a frequency that cut through the noise of heels, voices and Diana Krall’s background crooning, and beamed into her eardrum.

She turned.

‘You rang him four times the same night, the last was at twenty-six minutes to two.’ Harry had taken a bar stool. Isabelle Skoyen retraced the three metres. She towered over him. Harry was reminded of Little Red Riding Hood and the Wolf. And she was not Little Red Riding Hood.

‘What do you want, Harry boy?’ she asked.

‘I want to know everything you know about Gusto Hanssen.’

The nostrils on Axe-Nose flared and her majestic breasts rose. Harry noticed that her skin had large black pores, like dots in a comic strip.

‘As one of the few people in this town concerned about keeping drug addicts alive I’m also one of the few to remember Gusto Hanssen. We lost him, and that’s sad. These calls are because I have his mobile number saved on my phone. We had invited him to a meeting of the RUNO committee. I have a good friend whose name is similar, and sometimes I hit the wrong key. That sort of thing can happen.’

‘When did you last meet him?’

‘Listen here, Harry Hole,’ she hissed under her breath, stressing Hole and lowering her face even closer to his. ‘If I’ve understood correctly you are not a policeman, but someone who works with clothes and shoes. I see no reason to talk to you.’

‘Thing is,’ Harry said, leaning back against the counter, ‘I’m very keen to talk to someone. So if it isn’t you, it’ll be a journalist. And they’re always so pleased to talk about celebrity scandals and the like.’

‘Celebrity?’ she said, turning on a radiant smile aimed not at Harry but a suit-clad man standing by the head waiter and waving back with his fingers. ‘I’m just a council secretary, Harry. The odd photo in the papers doesn’t make you a celebrity. Look how soon you’re forgotten.’

‘I believe the papers see a rising star in you.’

‘Do you indeed? Perhaps, but even the worst tabloids need something concrete, and you have nothing. Calling the wrong number is-’

‘-the sort of thing that can happen. What cannot happen, however

…’ Harry took a deep breath. She was right; he had nothing on her. And that was why it was not a great idea to play it direct. ‘… is that blood of the type AB rhesus negative appears by chance in two places on the same murder case. One person in two hundred has that group. So when the forensics report shows the blood under Gusto’s nails is AB rhesus negative and the papers say that’s your group, an ageing detective cannot help but put two and two together. All I need to do is ask for a DNA test, then we’ll know with a hundred per cent certainty who Gusto stuck his claws into before he died. Does that sound like a somewhat above-average interesting newspaper headline, Skoyen?’

The council secretary kept blinking, as though her eyelids were trying to activate her mouth.

‘Tell me, isn’t the Crown Prince in the Socialist Party?’ Harry asked, scrunching up his eyes. ‘What’s his name again?’

‘We can have a chat,’ Isabelle Skoyen said. ‘Later. But then you’ll have to swear to keep your mouth shut.’

‘When and where?’

‘Give me your number and I’ll phone you after work.’

Outside, the fjord glinted and flashed. Harry put on his sunglasses and lit a cigarette to celebrate a well-accomplished bluff. Sat on the edge of the harbour, enjoying every drag, refused to feel the gnawing that persisted, and focused on the meaninglessly expensive toys the world’s richest working class had moored alongside the quay. Then he stubbed out the butt, spat in the fjord and was ready for the next visit on the list.

Harry confirmed to the female receptionist at the Radium Hospital that he had an appointment, and she gave him a form. Harry filled in name and telephone number, but left ‘Firm’ blank.

‘Private visit?’

Harry shook his head. He knew this was an occupational habit with good receptionists: seeing the lie of the land, collecting information about people who came and went and those who worked on the premises. If, as a detective, he needed the low-down on everyone in an organisation he made a beeline for the receptionist.

She pointed Harry to the office at the end of the corridor. On his way there Harry passed closed office doors and glass panes looking onto large rooms, people wearing white coats inside, benches littered with flasks and test-tube stands and big padlocks for steel cabinets Harry guessed would be an El Dorado for any drug addict.

At the end Harry stopped and, to be on the safe side, read the nameplate before knocking on the door: Stig Nybakk. He had barely knocked once when a voice reverberated: ‘Come in!’

Nybakk was standing behind the desk with a telephone to his ear, but waved Harry in and indicated a chair. After three ‘Yes’s, two ‘No’s, one ‘Well, I’m damned’ and a hearty laugh, he rang off and fixed a pair of sparkling eyes on Harry, who true to form had slumped in a chair with his legs stretched out.

‘Harry Hole. You probably don’t remember me, but I remember you.’

‘I’ve arrested so many people,’ Harry said.

More hearty laughter. ‘We went to Oppsal School. I was a couple of years below you.’

‘Young kids remember the older ones.’

‘That’s true enough. But to be frank I don’t remember you from school. You were on TV and someone told me you’d been to Oppsal and you were a pal of Tresko’s.’

‘Mm.’ Harry studied the tips of his shoes to signal he wasn’t interested in moving into private territory.

‘So you ended up as a detective? Which murder are you investigating now?’

‘I’m investigating a drugs-related death,’ Harry started, to keep as close as possible to the truth. ‘Did you get a look at the stuff I sent you?’

‘Yes.’ Nybakk lifted the receiver again, tapped in a number and scratched feverishly behind his ear while waiting. ‘Martin, can you come in here? Yes, it’s about the test.’

Nybakk rang off, and there followed three seconds of silence. Nybakk smiled; Harry knew his brain was scanning to find a topic to fill the pause. Harry said nothing. Nybakk coughed. ‘You used to live in the yellow house down by the gravel track. I grew up in the red house at the top of the hill. Nybakk family?’

‘Right,’ Harry lied, demonstrating again to himself how little he remembered of his childhood.

‘Have you still got the house?’

Harry crossed his legs. Knowing he couldn’t have the match called off before this Martin came. ‘My father died a few years ago. Sale dragged a bit, but-’

‘Ghosts.’

‘Pardon?’

‘It’s important to let the ghosts out before you sell, isn’t it? My mother died last year, but the house is still empty. Married? Kids?’

Harry shook his head. And played the ball into the other half of the field. ‘But you’re married, I can see.’

‘Oh?’

‘The ring.’ Harry nodded towards his hand. ‘I used to have an identical one.’

Nybakk held up the hand with the ring and smiled. ‘Used to? Are you separated?’

Harry cursed inside. Why the hell did people have to chit-chat? Separated? Course he was separated. Separated from the person he loved. Those he loved. Harry coughed.

‘There you are,’ Nybakk said.

Harry turned. A stooped figure wearing a blue lab coat squinted at him from the door. Long, black fringe that hung over a pale, almost snow-white, high forehead. Eyes set deep in his skull. Harry had not even heard him coming.

‘This is Martin Pran, one of our best scientists,’ Nybakk said.

That, Harry thought, is the Hunchback of Notre-Dame.

‘Eh, Martin?’ Nybakk said.

‘What you call violin is not heroin but a drug similar to levorphanol.’

Harry noted the name. ‘Which is?’

‘A high-explosive opioid,’ Nybakk intervened. ‘Immense painkiller. Six to eight times stronger than morphine. Three times more powerful than heroin.’

‘Really?’

‘Really,’ Nybakk said. ‘And it has double the effect of morphine. Eight to twelve hours. If you take just three milligrams of levorphanol we’re talking a full anaesthetic. Half of it through injection.’

‘Mm. Sounds dangerous.’

‘Not quite as dangerous as one might imagine. Moderate doses of pure opioids like heroin don’t destroy the body. No, it’s primarily the dependency that does it.’

‘Right. Heroin addicts die like flies.’

‘Yes, but for two main reasons. First of all, heroin is mixed with other substances that turn it into nothing less than poison. Mix heroin and cocaine, for example, and-’

‘Speedball,’ Harry said. ‘John Belushi-’

‘May he rest in peace. The second usual cause of death is that heroin inhibits respiration. If you take too large a dose you simply stop breathing. And as the level of tolerance increases you take larger and larger doses. But that’s the interesting thing about levorphanol – it doesn’t inhibit respiration nearly as much. Isn’t that right, Martin?’

The Hunchback nodded without raising his eyes.

‘Mm,’ Harry said, watching Pran. ‘Stronger than heroin, longer effect, and little chance of OD’ing. Sounds like a junkie’s dream substance.’

‘Dependency,’ the Hunchback mumbled. ‘And price.’

‘Excuse me?’

‘We see it with patients,’ Nybakk sighed. ‘They get addicted like that.’ He snapped his fingers. ‘But with cancer patients dependency is a non-issue. We increase the type of painkiller and dosage according to a chart. The aim is to prevent pain, not to chase its heels. And levorphanol is expensive to produce and import. That might be the reason we don’t see it on the streets.’

‘That’s not levorphanol.’

Harry and Nybakk turned to Martin Pran.

‘It’s modified.’ Pran lifted his head. And Harry thought he could see his eyes shining, as if a light had just been switched on.

‘How?’ Nybakk asked.

‘It will take time to discover how, but it does appear that one of the chlorine molecules has been exchanged for a fluorine molecule. It may not be that expensive to produce.’

‘Jesus,’ Nybakk said. ‘Are we talking Dreser?’

‘Possibly,’ Pran said with an almost imperceptible smile.

‘Good heavens!’ Nybakk exclaimed, scratching the back of his head with both hands in his enthusiasm. ‘Then we’re talking the work of a genius. Or an enormous flash in a pan.’

‘Afraid I’m not quite with you here, boys,’ Harry said.

‘Oh, sorry,’ Nybakk said. ‘Heinrich Dreser. He discovered aspirin in 1897. Afterwards he worked on modifying diacetymorphine. Not a lot needs to be done, molecule here, molecule there, and hey presto, it fastens on to other receptors in the human body. Eleven days later, Dreser had discovered a new drug. It was sold as cough medicine right up until 1913.’

‘And the drug was?’

‘The name was supposed to be a pun on a brave woman.’

‘Heroine,’ Harry said.

‘Correct.’

‘What about the glazing?’ Harry asked, turning to Pran.

‘It’s called a coating,’ the Hunchback retorted. ‘What about it?’ He faced Harry but his eyes were elsewhere, on the wall. Like an animal hunting for a way out, Harry thought. Or a herd animal that did not want to meet the hierarchical challenge of the creature looking you straight in the eye. Or simply a human with slightly above-average social inhibitions. But there was something else that caught Harry’s attention, something about the way he was standing, his crooked posture.

‘Well,’ Harry said, ‘Forensics says that the brown specks in violin originate from the finely chopped glazing of a pill. And it’s the same… coating you use on methadone pills that are made here at the Radium Hospital.’

‘So?’ Pran riposted.

‘Is it conceivable that violin is made here in Norway by someone with access to your methadone pills?’

Stig Nybakk and Martin Pran exchanged glances.

‘Nowadays we deliver methadone pills to other hospitals as well, so quite a few people have access,’ Nybakk said. ‘But violin is high-level chemistry.’ He expelled air between flapping lips. ‘What do you reckon, Pran? Have we got the competence in Norwegian scientific circles to discover such a substance?’

Pran shook his head.

‘What about by fluke?’ Harry asked.

Pran shrugged. ‘It is of course possible that Brahms wrote ein deutsches Requiem by fluke.’

The room fell silent. Not even Nybakk appeared to have anything to add.

‘Well,’ Harry said, getting up.

‘Hope that was of some help,’ Nybakk said, extending his hand to Harry across the desk. ‘Say hello to Tresko. I suppose he still does nights at Hafslund Energy, keeping his finger on the electricity switch for the town?’

‘Something like that.’

‘Doesn’t he like daylight?’

‘He doesn’t like hassle.’

Nybakk gave a tentative smile.

On his way out Harry stopped twice. Once to examine the empty laboratory in which the light had been turned off for the day. The second time was outside the door displaying Martin Pran’s nameplate. There was light under the door. Harry carefully pressed the handle. Locked.