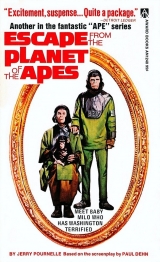

Текст книги "Escape from the Planet of the Apes"

Автор книги: Jerry Pournelle

Жанры:

Альтернативная история

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 6 (всего у книги 10 страниц)

TWELVE

“That could have been sticky,” Lewis said. He sipped his coffee and relaxed in the apes’ hotel suite. “You can be certain they aren’t through, either.”

“It was nice of Dr. Hasslein to adjourn the meeting,” Zira said. “I didn’t like him at first, but he seems to be a nice man.”

“Maybe,” Lewis said. “Nice or not, he’s important. Nobody seems to know him well. I don’t think he has any personal life at all.”

“Certainly he does,” Stevie said. “I’ve met his wife and children. He’s no monster, Lewis. A little cold, perhaps, but he’s very pleasant when he wants to be.”

“When did you meet his family?” Lewis asked.

“At school. It must have been, oh, a year or two ago. There was an advisory group coming through to review grant applications, and Dr. Hasslein was one of the reviewers. He brought his wife, and the dean asked me to entertain her. Turned out he’d brought two kids, too. He has three, but only the older two came.”

“What’s Mrs. Hasslein like?” Lewis asked curiously. The chimps listened with interest.

“Well, she’s not very big, really, but she gives the impression that she is,” Stevie said. “You know, she acts like an old mother hen. It seems a little out of place in such a small girl. But she keeps the children in line very nicely. Especially the—you know.”

Lewis frowned. “I know what?”

“Oh—you didn’t know,” Stevie said. “Well, one of the children is mongoloid. He’s about fourteen years old, with the intelligence of a six– or seven-year-old child.”

“Poor Mrs. Hasslein,” Zira said.

“She doesn’t let it bother her,” Stevie told them. “And they’ve done wonders with the boy. You wouldn’t think he could have learned so much. Dr. Hasslein is very patient with him. I watched them together.”

“He’s showing me around the Museum of Natural History tomorrow,” Zira said. “I understand they have some marvelous specimens there. In our time there were so many species known only through records, thousands of extinct species. It should be interesting to see them displayed in their natural habitats.”

“I suppose so, my dear,” Cornelius said. “I think, though, I should go with you.”

“Nonsense,” Zira said. “You have an appointment with that British historian chap tomorrow and it’s the only chance you’ll have to see him. I’d be bored stiff sitting through that. It was nice of Dr. Hasslein to offer to show me around.”

“Watch what you say to him,” Lewis warned. “I don’t know what his game is, but I don’t trust him.”

“That’s silly,” Zira said. “If we’re going to be suspicious, then he’ll have a right to be suspicious of us. Pretty soon, nobody will trust anybody, and then where’ll we be?”

“You can’t trust him now,” Cornelius reminded her. “You weren’t thinking of telling him the entire story, were you, my dear?”

“No. I won’t without your permission. But I don’t like this deceit, I really don’t. It’s not natural.”

Cornelius laughed. After a few moments the others did also. “Interspecies trust,” Cornelius said. “A new first.”

“And I hope it lasts,” Stephanie added.

A highly colorful display of the life cycle of the Monarch butterfly; a collection of birds, stuffed or skinned; rhino models; models of the Indian civilizations of the southwest, including a large model of the Aztec City of the Sun; all these and more. Zira rushed from one display to another, laughing joyfully, and driving her escorts half crazy as they tried to keep up with her.

There was a large mockup of a hurricane, baleful eye of the storm calm in the midst of whirling winds. The artist had drawn it perfectly, and it was framed by satellite pictures of real hurricanes. Next to it was a display of photographs: the destruction of Bangladesh by the great typhoon of 1970.

“How many were killed?” Zira asked.

Hasslein looked pained. “Hundreds of thousands. No one knows for sure. Possibly as many as half a million people.”

“I don’t think there were that many apes, or humans, on earth in my time,” Zira said. They went on through the meteorology section to a display of dinosaur bones and models.

“Do you know what happened to all those people?’ Hasslein asked. “There are nearly three billion on earth now. Perhaps more.”

Zira pointed to the dinosaurs. “What happened to them?”

“We are not sure,” Hasslein said. “It was apparently time for them to go. They went. Perhaps small mammals developed and ate the eggs of the big lizards. Perhaps the climate changed and they could no longer get enough to eat. No one is certain. But do you think it is time for the human race to leave the earth?”

“It hadn’t in my time,” Zira said.

“But apes were dominant,” Hasslein prompted. “Humans did not talk and had no civilization . . .”

“Not in my part of the world,” Zira said. “I suppose I’m getting tired. Perhaps we should go now. It’s been a very nice day.”

“And it can still be,” Hasslein said smoothly. “I will not press you again. You do understand, it’s a question that is very important to me. To all of us. What can have happened to the human race? Perhaps we are about to make some mistake—a mistake we can do something about.”

“But—” Zira stopped and looked at him. Her eyes widened. “Do you think you can change the future? We came from the future! What we saw had already happened!”

“But it has not happened yet,” Hasslein said. He was very serious. “And thus need not happen.”

“But—what of us?” Zira demanded. “If you do something to prevent our world from ever existing, won’t Cornelius and I just—vanish?”

Hasslein shook his head. “I doubt it. You are here. You are part of the present, not the future, even though you came from the future.”

Zira shrugged and turned away. She began to walk down the corridor again, her heels clicking against the tiled floor. “I don’t think I understand all this, and it gives me a headache.”

Hasslein laughed. “It does me, too.” They turned the corner and entered the primate room.

The display was dominated by the centerpiece: an 800 pound male gorilla, magnificently erect, with clenched fists. His dead, glassy eyes stared at the door and seemed to bore through Hasslein and Zira. Around him there were other displays, but he seemed to fill the room, to grow larger and larger, until Zira could see nothing else.

The room seemed to swirl about, and Zira felt dizzy. Slowly she fell against Hasslein. The scientist held her for a moment, then gently lowered her to the floor. The attendants ran up.

“What’s wrong?”

“Can we do anything?’’

“Send for Dr. Dixon,” Hasslein said. “Are you all right, Zira?”

“It must have been the shock of the gorilla,” a Marine bodyguard said.

Zira opened her eyes. “Shock, my foot. I’m pregnant.”

“Good Heavens,” Hasslein said. “And we’ve worn you out with all this walking and looking. Let’s get you home.”

“Dr. Dixon will be here soon,” Victor Hasslein said. “Are you sure you are all right? The ride back home didn’t tire you too much?”

“I’m fine. You can go now, Dr. Hasslein. Thank you.”

“Oh, no, Zira,” Hasslein said. “I shan’t leave you until Cornelius or Dr. Dixon get here. No, no, I insist. Is there anything I can get you?”

She leaned back on the couch and kicked off her shoes, sighing in relaxation. “Well, I have a strange craving—”

“That’s only natural under the circumstances. What can I get you?”

“Grape Juice Plus.”

“What? I’m afraid I don’t understand.”

“It’s in the refrigerator,” Zira said. “Re-frig-er-a-tor. I said it right, didn’t I? We call it an icebox.”

“Refrigerator. Certainly. I’ll get it.” Hasslein went to the suite kitchenette. There were three bottles of California champagne in the refrigerator, and he smiled softly to himself. He looked through the cupboards until he found a large wine goblet, then opened the champagne and filled the glass. He brought the bottle with him into the living room.

“Here you go,” he said. “Grape Juice Plus.” Hasslein winked at Zira.

She winked back. “But I shouldn’t drink this much . . .”

“Oh, come now,” Hasslein said. “You’re not that far along, are you?”

“Pretty far,” Zira said.

“Well, a little champagne never hurt anyone. How long have you known you were—uh, going to have a child?”

“Since well before the war.” She took a deep drink of the champagne and smacked her lips. “That’s very good. Anyway, I knew since before the war, and that was another reason we wanted to escape. We couldn’t know what would happen.”

Hasslein took out his cigarette case and set it on the table. “Perhaps I shouldn’t smoke—”

“Oh, it doesn’t bother me,” Zira said. “It seems a very silly habit, though.”

“It is. One much easier to take up than to quit, it seems. Thank you.” He lit a cigarette, and left the case on the coffee table in front of the couch. “You say you don’t know against whom the war was fought?”

“Not really,” Zira said. She took another gulp of champagne. Hasslein casually filled her glass again. “Just that there were some—uh, apes, living underground in the next district, and the army decided to fight them.“

Hasslein nodded agreement. “Ordinary citizens often are not asked about such things. Who won your war?”

“It wasn’t our war,” Zira protested, her speech slurring. She gulped more wine. “It was the gorillas’ war. They’re always fighting about something. Chimpanzees are pacifists. We never did see an enemy.”

“Oh.” Hasslein filled her glass again, then took a seat and stretched his feet out in front of him. “Hard day today, wasn’t it?”

“A little,” Zira agreed. They chatted about the museum for a while, as Hasslein continued to keep her glass full.

“Surely you know which side won the war,” Hasslein said finally.

“Neither side won,” Zira said. “The stupid fools. We told them . . .”

Hasslein frowned. “Just what did happen, then?”

“When we were in space . . . we saw the light. A blinding bright white light, it was horrible. The rim of the world seemed to melt! The whole earth must have been destroyed. Dr. Milo thought it had been. Then there was—I don’t know. Then we were here.” She lifted her glass again and drank more wine, spilling several drops on the table and drooling more down her chin.

“I feel very sleepy,” she said. “Magnificently sleepy. I think I shouldn’t drink any more.”

“Probably you’re right,” Hasslein agreed. “Tell me, Zira, what was the date in your time?”

“Thirty-nine . . . fifty-five.”

Hasslein whistled. “That’s a long time from now. Nearly two thousand years. How far back did you have records?”

“I don’t know. Cornelius would have better information. We had some records, copies of human records, that go back into your past, Dr. Hasslein. But we didn’t have details of anything much over a thousand years old.”

“I see. You are getting sleepy, and here comes Dr. Dixon. He’ll see you get to bed.” Hasslein retrieved his cigarette case as Lewis came in.

“You’re all right?” Lewis demanded. “I was told she had a fainting spell.”

“Nothing to be worried about,” Hasslein assured him. “But perhaps you don’t know. Madame Zira will be a mother shortly. I’ll leave you with your patient, Dr. Dixon. Good afternoon.”

Lewis watched Hasslein put his cigarette case in his pocket and leave the suite. He watched until the scientist was gone, and then turned to Zira, noting the nearly empty champagne bottle, and Zira’s slack smile. Just what had Hasslein learned? And what would he do with the knowledge? Lewis Dixon was suddenly afraid.

THIRTEEN

It was warm in Washington, far too warm, and the president wished he were back in the Western White House in California. If it were left to him he’d move the whole government out there, except it couldn’t really be done. All those bureaus and bureaucrats—of course, he could do without a lot of them, but not without the embassies. He sighed again thinking about California, then buzzed his secretary.

“Who’s next, Mary Lynn?”

“Dr. Hasslein, Mister President.”

“Oh.” He sighed again. What would Victor want this time? He seemed so upset about the chimpanzees. “All right. Send him in.”

Hasslein came, into the oval office and stood, straight and still, in front of the president’s desk. Except for the military people, Hasslein was the only man who stood quite that way, and the president often wondered if the scientist were a frustrated soldier.

“What can I do for you, Victor?”

“I made a tape last week, Mister President. While I interviewed the female chimpanzee. I’d like you to listen to it.”

“All right.” The president got up from behind the big desk and came around to the couch on the other side. He motioned Hasslein to a chair. “Can I get you anything, Victor? A beer, perhaps? I’ll have one myself.”

“No, thank you, sir.” He set the small tape recorder/player on the coffee table and waited until the president had opened the beer he took from the refrigerator under the end table.

“Just how did you get that tape?”

“With a clandestine recorder the CIA people gave me. A cigarette case.” Hasslein started the tape. It began with his own voice—“How long have you known you were—uh, going to have a child?” Zira answered. Eventually it ended.

The president drank the last of his beer. “So?”

“So?” Hasslein stood and paced angrily. “So Mister President, we have evidence that some day talking apes will dominate the earth. They will live in a civilization, if you can call it that, with very little science and no technology. Humans will be dumb animals, probably mistreated. And in less than two thousand years those apes will destroy the earth, killing themselves and all humans as well.”

“I doubt we will be in office then,” the president said.

“Really, sir, I am serious.”

“So am I, Victor. I have an oath to uphold and defend the Constitution, and to preserve and protect the people and nation. I don’t see how these apes are much of a threat to that oath—or, for that matter, what I am supposed to do about a theoretical threat to the earth that doesn’t mature for almost two thousand years.”

Hasslein continued to pace. He said nothing.

“Come now,” the president said. “Victor, what the devil do you expect me to do about it? What can we do about it?”

“Mister President, can apes talk now?”

“Eh? Of course not, Victor.”

“After thousands—millions—of years of evolution, they can’t talk and don’t appear to be able to learn,” Hasslein said. “Had you asked me before those three appeared in that capsule, I would have said it was absolutely impossible for apes to learn to talk at any time within the foreseeable future. That it would be at least hundreds of thousands of years before they learn.”

“Yet we have two who can.”

“Precisely!” Hasslein smacked his left fist into his open right hand. “Because these two apes are genetically different! Yet, I expect, they can interbreed with other apes. They can transmit that distinguishing characteristic, the ability to learn speech, to their progeny. If that gene is distributed among apes, then all apes will eventually have the ability to speak.”

“Oh, come now, Victor, that’s a paradox! You’re saying that they come from the future to our present; they interbreed with other apes; and by interbreeding with them, they create their own future! That if they didn’t come here to be their own great-great grandparents, they couldn’t exist at all! You don’t really believe that, do you?”

“Yes, sir, I’m afraid that’s precisely what I believe.”

“Impossible! Rubbish!”

“No, sir.” Hasslein’s eyes blazed as he glared at the president. “I can prove it. What you think of as a paradox, as a violation of the laws of causality, only appears that way because you have a very distorted view of causality to begin with. Now, let me show you.” He took a sheaf of papers from his pocket and laid them on the table. “Look here—”

“Oh, no,” the president protested. “Victor, I never got past college algebra! You take those equations and put them back in your pocket.”

“But I can’t prove it to you without them.”

“We’ll assume you prove it, all right? But what do you want me to do?” He looked at the pale blazing eyes. “No! You really think we can alter the course of the future?”

“Yes, sir. Their future is not necessarily our future. Even though it is just as real. I can—”

“I heard you on the Big News show. Not that I understood you. So you want me to alter what you believe may be the future by slaughtering two innocents. Three, now that one of them’s pregnant.” The president nodded grimly to himself. “It’s an old tradition with kings, isn’t it? Herod tried it. He wasn’t successful, either. Christ survived.”

“Herod lacked the facilities we have,” Hasslein said grimly. “And we have only two apes to deal with.”

“Victor, have you any idea how unpopular such a thing would be?” the president demanded. “I’d go down in history as another Herod. No, thank you. I’ve a good record, and I don’t need that on it.”

“You are putting your sentiments for these apes ahead of your duty to the people.”

The president half stood, his mouth a grim, tight line of anger. “I do not need you to remind me of my duties to the people, Doctor Hasslein!”

“I beg your pardon,” Hasslein said formally.

“You beg it, but you aren’t sorry,” the president said. He sighed and sat down again. This interview wasn’t going well at all. “Victor, I’ve seen the chimpanzees on television, I’ve met them briefly—they seem very charming, very harmless, and very popular with the voters. You speak of my duties to the people. One of those duties is to carry out the popular will, and I think being courteous to those chimpanzees is very much what the people want.”

“Not all of them,” Hasslein said. “The Gallup poll shows a lot of undecided. Especially when they’re asked about Colonel Taylor—”

“Yes. But the fact remains, they’ve done nothing to us, and have made no threats. In God’s name, Victor, how would we justify anything like that?”

“It would look like a tragic accident,” Hasslein said. “The CIA could arrange it.”

“They could, eh? How do you know?”

“Well, sir, I assumed—”

“You can keep your assumptions to yourself, Dr. Hasslein. No. We will have no tragic accidents.”

“My God, Mister President, do you want them and their progeny to dominate the world?”

The president smiled again. He went to his big chair behind the desk and sat, his eyes not focused but staring idly outside at the White House lawn. One of his children was playing out there. “Not just yet, certainly,” he said. “And not at the next election, either. But if their progeny turn out to be as pleasant as they are, maybe they’ll make a better job than we have. We haven’t done all that well, Victor.”

“They destroyed the earth!”

The president shrugged. “Are you sure that was our earth she saw destroyed?”

“Are you sure it wasn’t, Mister President?”

“Of course not.”

‘And it is a reasonable assumption. They believed it was the earth. It certainly sounded like it. These animals are native to Earth. They therefore came from our earth—”

“Oh, spare me the long-winded logical arguments, Victor. You may be right . . .”

“The earth, Mister President. All of it. Leave out the fact that these apes have conquered our earth in their time; that humanity consists of sniveling wretches unable even to pronounce their own names. Perhaps something could have been done about that. But not with the earth destroyed!”

“Victor, if that is the future, nothing we do will change it.”

“Insufficient understanding again, Mister President. All futures may be equally real, but only one will happen.”

“I’m afraid I don’t understand how something can be real if it doesn’t happen—oh, never mind. I don’t want you to explain it again. You truly believe that by deliberate, present-day action we can change the future for the better.”

“Yes. I do.”

“All right. But do you believe we should? Have we got the right to do that, Victor?”

“I don’t know.”

The president looked up, shocked. It was the first time he had ever seen his science advisor in a state of uncertainty. The man’s wild stare was gone, and there were suspicious glints at the corners of his eyes, as if he were about to cry.

Hasslein’s voice was unsteady as he continued. “You can’t know how I’ve wrestled with that problem, Mister President. I just don’t know what the right thing is. Out of all the futures, all real, which one has God chosen for man’s final destiny? And if we destroy those apes, are we defying God’s will or carrying it out? Are we His instruments or His enemies?”

The president got up from his desk and went to put a hand on Hasslein’s shoulder. “I wouldn’t worry too much about thwarting God’s will, Victor.”

“I can’t believe in fatalism—”

“Nor I, Victor. I only meant He’s big enough to get His way if He sets His mind to it, without much regard for what you or I want. Maybe you’d better ask Him what to do. I do. Quite often, in this job.”

Hasslein shook his head. “I don’t know how.”

“Then I do feel sorry for you. But you do know that killing two innocent beings is immoral. You can’t condone that kind of assassination—”

“You have,” Hasslein protested. “We had that Soviet marshal killed—”

“God help us. Yes. He was an evil man, full of plans for war. I had no choice.” The President noticed Hasslein’s triumphant look, and felt disgust. “Yes. I authorized murder of an evil and dangerous man, Dr. Hasslein. But I wouldn’t have approved killing him as a baby because he might become an evil man. Or having his remote ancestors killed to prevent his ever being born. That’s just what you’re proposing to do with those chimpanzees, and I won’t have it. They haven’t done anything to us.”

“Nothing proven,” Hasslein said. “The fact remains, they have appeared in Colonel Taylor’s capsule. The very act of their coming here makes it impossible for Colonel Taylor to return. Don’t forget that, Mister President. They may have killed Colonel Taylor for his ship. Did you ever think of that?”

The president sat abruptly. “No. I didn’t.”

“Suppose that’s the way it happened?” Hasslein asked.

“Then we would have to rethink our position,” the president said. “Taylor was one of my officers. I sent him. What makes you think these chimpanzees know any more than they’ve told us?”

“They didn’t tell us about the end of the world,” Hasslein reminded him. “Not until I got one of them drunk.”

“Plying a pregnant girl with champagne,” the president said. He almost smiled. “I ought to be ashamed of you.”

“It got more information than anything else we’ve done,” Hasslein snapped. “And there have been other discrepancies. I think those chimpanzees are lying to us. About many things. I think proper interrogation would disclose what they were lying about.”

“And you don’t think the Commission is competent?” the president asked.

“No, sir. How could it be? And its procedures are those of Anglo Saxon justice. I submit to you, sir, this is a matter of national security, and those apes have no rights under the Constitution of the United States.”

“I suppose not,” the president said. “I take it, then, you want your own interrogation—?”

“Yes, sir. I want to borrow some people from the National Security Agency, and I want to transfer this matter to the National Security Council instead of that farcical Commission.”

The president nodded. He lifted a telephone from his desk and spoke briefly into the instrument, then turned to Hasslein again. “All right. I’ve asked General Brody to set things up with NSA for you. As to the Commission, you will give all information NSA digs up for you to the commissioners. I will not remove this matter from their jurisdiction until and unless I think there is a real threat to the national security. You keep me informed, and until you find me something really convincing, the Commission stays on the job. Agreed?”

“Yes, sir,” Hasslein said. “Thank you.”

“You needn’t,” the President said. “I don’t like any of this. But you’ve effectively reminded me of my duty. Very well, Victor. Keep me informed.”

“Yes, sir.” Hasslein left, a twisted smile on his face.

The president watched the door close behind his science advisor, and sighed again. There were times when he wondered if all the fight he’d had to get to this office had been worth it; if he wouldn’t be happier back in Congress. He’d always liked politics, but the oval office was a pretty big job for an Iowa farm boy.

It would be pretty big for anybody, he thought. And the man who had wanted it, the man I defeated to get it—God, no. “Mary Lynn, who do we have next?”

“Secretary of the Interior, sir.”

“Very good. Send him in.”