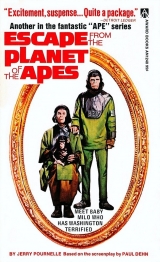

Текст книги "Escape from the Planet of the Apes"

Автор книги: Jerry Pournelle

Жанры:

Альтернативная история

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 10 страниц)

ESCAPE FROM THE PLANET

OF THE APES

The time indicator raced back through the years—from 3955 to 1973. The spacecraft held the Earth's future inhabitants—three survivors of a devastating cataclysm.

The capsule's occupants included Cornelius, his mate Zira, and Dr. Milo—three Apes, the thinking, speaking descendants of the species that had dominated Man and the Earth for centuries.

The world of 1973 welcomed them at first, pampered them when it realized their unusual qualities, threatened them later when it was learned that Zira carried the seed of the future ascendance of Ape over Man.

They had to be killed! But first . . .

20th Century-Fox Presents

An Arthur P. Jacobs Production

ESCAPE FROM THE PLANET

OF THE APES

Starring

RODDY McDOWALL • KIM HUNTER

BRADFORD DILLMAN • NATALIE TRUNDY

ERIC BRAEDEN • WILLIAM WINDOM • SAL MINEO

and

RICARDO MONTALBAN

as Armando

Produced by

APJAC PRODUCTIONS

Directed by

DON TAYLOR

Written by

PAUL DEHN

Based on Characters from

PLANET OF THE APES

Music by

JERRY GOLDSMITH

ESCAPE FROM THE PLANET OF THE APES

FIRST AWARD PRINTING January 1974

Copyright © 1971, 1973 by

Twentieth Century-Fox Film Corporation.

All rights reserved

AWARD BOOKS are published by

Universal-Award House, Inc., a subsidiary of

Universal Publishing and Distributing Corporation,

235 East Forty-fifth Street, New York, N.Y. 10017

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

CONTENTS

Title

Copyright

Dedication

About the Author

ESCAPE FROM THE PLANET

OF THE APES

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-One

Twenty-Two

Twenty-Three

TO: P. Schuyler Miller

and L. Sprague de Camp

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Jerry Pournelle is currently president of the Science Fiction Writers of America. He is the recipient of the John W. Campbell Memorial Award for the best new science fiction writer since 1971. His novella, The Mercenary, has been nominated for a 1973 Hugo Award.

Mr. Pournelle was intimately involved in the U.S. space program from 1956 to 1968. He is married, the father of four boys, and his wife teaches in a correctional institution. Unlike many of his SF writer friends he prefers dogs to cats, and has a Husky named Klondike. Mr. Pournelle is currently writing a regular science fact column for Galaxy magazine.

ONE

It was two o’clock in the afternoon with bright sunshine and cloudless skies over Omaha. A gentle wind flowed out of the northwest, and the temperature was seventy, nearly perfect weather. It would have been a marvelous day for a picnic.

Major General Raymond Hamilton, USAF, knew this because the weather over each of his Strategic Air Command bases was displayed on the command status board above his desk in the hole. Otherwise, Omaha’s weather wouldn’t interest him for another six hours. It would be night before he went off duty and home to his wife and two boys and the red brick house originally built for the U.S. Cavalry before the turn of the century. Now the cavalry wasn’t needed to stand guard over Omaha. Instead, the old fort was Offutt Air Force Base, home of SAC, and SAC stood guard over the world.

General Hamilton’s desk was three stories underground. It rested on a glassed-in balcony overlooking the main SAC command post, and two floors further down, directly below and in front of Hamilton’s balcony, were the Air Force personnel who could put him in communication with any SAC base. They could also launch enough nuclear firepower to destroy half the world.

Among the telephones on Hamilton’s desk were two in color. The gold phone would instantly reach Executive One—the president. Next to it was the red phone that could launch the force.

Ray Hamilton wasn’t thinking about the red phone at two in the afternoon. The president’s summit conferences had been successful, and although Ray, like all SAC generals, believed the Russians were planning something and had to be watched at all times, he didn’t believe the “Big One” was coming just yet. If SAC stayed alert, it might never come. Ray was relaxed in his easy chair, leafing through a murder mystery. He grimaced as he realized he’d read it before and faced the afternoon with nothing to do.

General Hamilton was bored. If he worried about anything, it was about his son’s bicycle. That was the third ten-speed stolen from his family in less than two years, and it irritated him to think that SAC could guard the free world, but SAC’s Air Police couldn’t catch a bicycle thief. The boy had to ride a mile to high school and would need a new bike, and that would cost money Ray Hamilton didn’t have at the moment.

A phone rang. A black one. Hamilton picked it up. “SAC Duty Commander.”

“SAC, this is Air Defense. We have a bandit re-entry coming in over the South Pole. I say again we have a bandit on re-entry course over the South Pole. Probable place of impact, vicinity of San Diego, California. Estimated time, plus 26 minutes.”

Hamilton tensed. “NORAD, this is SAC. Are you sure you have a bandit?”

“Affirmative, SAC. We have no previous plot. Bandit has no previous orbital flight. Launch point unknown. This is a big one. Estimated excess of 35,000 pounds.”

“My God!” Ray Hamilton looked across at the enormous screens on the opposite wall. His staff had already projected a map of the Western Hemisphere and the predicted path of the intruder. The red dotted line led from the bandit’s position over Chile up to a large circle just north of San Diego. Hamilton scowled. The Soviets had tested a 100 megaton bomb, and a vehicle that size could carry one. That thing would take out most of Southern California, including Oceanside. Hamilton’s status board showed Executive One in residence at the Western White House.

Suddenly he felt very calm. His voice was unemotional as he spoke into the black phone. “NORAD, this is SAC. Thank you. Send any additional update information. SAC out.” He laid the black phone down and hesitated a second. Then he lifted the red one.

A siren blared through the hole. Red lights flashed. That phone was no joke. Hamilton’s throat was dry as he spoke in the unemotional voice of command, “All units, this is SAC. EWO, EWO. Emergency War Orders. This is no drill. Yellow alert. All units, Yellow alert. March Air Base, generate your aircraft wings. I say again, March Air Force Base only, generate the force. SAC out.” He nodded, and the duty officers below him began feeding the authentication codes that would confirm his orders.

Across the country men responded. Pilots tumbled from their ready-room bunks and raced across runways to their ships. Within minutes the B-52’s and B-58’s were cocked and ready, engines idling, as their pilots waited for the orders that would launch them toward the north. Each carried maps to half a dozen targets around the world. They would learn which to head for once they were airborne.

In forty holes across the northern United States, USAF officers took keys from around their necks and inserted them into gray consoles. They did not, as yet, turn the keys. Above them, sergeants locked steel doors three feet thick into place; the missile commanders were sealed in and would be until the alert was over. Around the missile farms the Minuteman missiles came alert, gyros hummed, computers took in last-second data.

At March Air Force Base, Riverside, California, a wing of B-52’s rolled down the runway and took off, the last airborne less than fifteen minutes from the time Ray Hamilton gave his orders. Each ship carried four twenty megaton bombs in its belly, and two more in stand-off missiles hung under the wings. The ships left faint vapor trails in the California sky as they flew northward toward their rendezvous with the tankers. Navigators handed up course data to the pilots, then looked back at their charts. On each chart was a dark black line. When the planes reached that line, they would turn back—unless they had received orders from the president to go on in. The pilots flew grimly, silent, waiting, some praying, hoping for cancellation orders . . .

General Ray Hamilton lifted the black phone again. “NORAD, do we have any additional bandits?”

“Negative, SAC. It’s a single object on a ballistic re-entry, automatic sequencing. Not under command so far as we can tell. Pretty big to be a bomb. Too open. I think it’s experimental.”

“So do I.” Hamilton waited. He could call the president, but there’d be no point. If that was a bomb set to detonate at optimum altitude over Oceanside it would take out the president, March AFB, San Diego Navy Yards, Miramar, Long Beach, and a lot of Los Angeles. There would be no way to get the president out in time. And if it blew, there’d be no question about a hostile move against the United States.

It probably wasn’t. It was too big and too open. Probably the force would be recalled, and SAC would have had another drill. They had them every week anyway.

“All right, NORAD,” Hamilton ordered. “Give me what you get as it comes in. Have you got an intercept launched yet?”

“Affirmative, SAC.”

“Patch me in.”

“Roger, SAC.”

There was a lot of static and several squeals; then Hamilton could hear the pilot of the interceptor flying above the probable area of the bandit’s impact. Ray glanced at his status board. The March AFB wing of 52’s was on its way and out of the danger area. At other bases the ships waited still. His SAC force was poised like a cocked crossbow, and the red phone could launch the greatest concentration of firepower in the history of the world.

Not without permission from Executive One, of course. Ray waited; in a few minutes, he’d know. There would be no point in launching, or Executive One wouldn’t care. SAC would own its own planes and missiles again, and SAC would take a terrible vengeance for the president.

“NORAD, this is Red Baron Leader. I have visual on the bandit,” came the interceptor pilot’s voice, cold and unemotional.

“Roger, Red Baron Leader. Describe.”

“Bandit is lifting body spacecraft with NASA markings. Spacecraft is descending with air speed approximately mach 2.6 slowing rapidly. Spacecraft appears oriented properly for splashdown with low g-stress.”

“Red Baron Leader, say again ID of spacecraft.”

“Spacecraft appears to be United States NASA lifting-body ship. I can see the NASA insignia. I say again, spacecraft has US NASA markings. It’s going to splash. It looks to be under control.”

“Red Baron Leader, follow that spacecraft down to splash and stand by to direct Navy recovery team to your location. MIRAMAR, this is NORAD. We have an unscheduled NASA spacecraft splashing in your air defense area. Can you get a recovery team out there pronto, interrogative?”

“Roger NORAD, this is Miramar. Helicopter recovery team will be on the way in five minutes. We will notify Fleet to send out a recovery ship.”

“SAC, this is NORAD. Get all that?”

“Roger, NORAD.” Hamilton shook his head slowly, then watched his status boards. The timers clicked off to zero; bandit was down. He heard the chatter of Red Baron Leader. The spacecraft had made a perfect landing and was afloat. Hamilton waited another minute, then lifted the red phone.

Again the sirens wailed. “All units, this is SAC. Cancel EWO. I say again, cancel Emergency War Orders. Return to alert status. March wing, return to base. SAC out.” He laid the red phone down and breathed deeply.

An unscheduled spacecraft screaming in for splashdown off San Diego from re-entry over the South Pole. Somebody in NASA was going to get his hide roasted for this. Hamilton hoped he’d be around to see it. In fact, he’d like to do the roasting. The incident had scared him, he would admit now that it was over.

In all his years in the Air Force, he’d been through plenty of alerts, but this was the first real one he’d commanded. Ray Hamilton said a short prayer that it would be the last. There wouldn’t be many survivors of a nuclear war.

TWO

The gold telephone rang, and the president hesitated a moment before answering. There were several of those gold phones throughout the U.S., and they didn’t all mean war, but he was scared every time it rang. He wondered what other presidents had thought when they heard it, and if they ever got used to it. Certainly he hadn’t, and he’d been in office over a year now. The phone rang again, and he lifted it.

“Yes.”

“Mister President, this is General Brody.” The president nodded. Brody was White House Chief of Staff. He wouldn’t be calling with a war message. “Sir, we’ve got a small problem out your way. One of NASA’s manned space capsules came in over the Pole and splashed just offshore from you, and SAC went to Yellow Alert.”

“What’s their status now?” he asked quickly.

“Back to normal alert status, Mister President.”

“A NASA spacecraft—I don’t recall that we’ve launched any manned capsules recently, General.”

“I don’t either, Mister President. Nor does NASA. But there’s sure as hell one up there—well, down now. Anyway, the Navy’s helicopter boys think this could be one of the ships lost a year ago. Colonel Taylor’s, for instance.”

“Eh?” The president pulled his lower lip. It was a famous gesture and he’d used it so often that it was genuine enough now, even if he had been advised to adopt it by his managers back when he was still in Congress. “What are the chances of its really being one of our ships? With the crew alive?”

“None, Mister President. That ship maneuvered into the water. It came in on automatic, but there was a pilot working the controls just before it splashed. Colonel Taylor’s been missing over a year. There weren’t enough supplies to keep the crew alive that long. No, sir, it can’t be our people coming back.”

“I see.” The President pulled his lip again. “Have you thought of this possibility, General—that the Russians retrieved one of our missing spacecraft and have now manned it with their own cosmonauts. Could there be Russians aboard that ship?”

The line hummed a moment as General Brody listened to a background voice the President couldn’t quite hear. Then his Chief of Staff came back on. “Sir, there could be anybody aboard that thing. The Navy’s bringing the capsule onto their recovery ship right now. Have you any instructions?”

“Yes. If there’s anyone alive on that thing, welcome them to the United States. Or to Earth, if they’re—uh, there’s always that possibility, isn’t there? That they’re little green men? Have Admiral Jardin use his judgment, General. Meanwhile, you get those NASA scientists to go over that ship with whatever’s the scientific equivalent of a fine-toothed comb. When they know anything, tell me. And General, I want full security on this operation.”

“Yes, sir.”

“You do understand me, don’t you, General? This is not for the networks.”

“Yes, sir.” General Brody cradled the phone and swore. He couldn’t blame the president. There’d been a lot of leaks to the press. The heavy sarcasm was probably deserved. Still, there were a lot of people who were easier to work for.

He lifted another telephone and dialed; then, as it was ringing, shouted, “Sergeant, where’s that TV monitor?”

“Coming up, General.” Three uniformed men rolled a color TV set into General Brody’s office. They fussed with the dials, and a picture formed. The camera was atop the island on the aircraft carrier, looking down onto the flight deck. Brody could just see waves over the side of the ship—a calm sea.

A crane lifted the space capsule out of the water and over the deck. There was no mistaking the NASA markings on the sides and the vertical stabilizer. Ugly ship, Brody thought. No wings. Just the body of the craft, bent, so that it would provide lift at high speeds. Pilots told him it had all the glide characteristics of a rock, but they were all willing to fly in it. With the cutbacks in the space program, there were five astronauts for every mission anyway.

The capsule was lowered to the deck with a thump. Sailors clustered around it. Brody’s phone rang and he answered absently.

“Admiral Jardin, sir,” the voice on the phone said.

“Put him on.” Brody continued to watch the spacecraft on the TV set. No one wanted to open it. Two Navy surgeons stood outside the hatch, watching, saying nothing. Admiral Jardin, with a phone, stood with them. Brody spoke into his phone. “You going to open that thing, Admiral? I’ve got a TV monitor here, I’m watching. The president says you’re to use your own judgment, but keep the reporters away.”

“We were wondering about quarantine, General,” Admiral Jardin said. The voice was gruff and hard, rasping. “Both ways. What might we catch from them, of course, but if they’ve been a long time in space they have been in a sterile environment. What might they catch from us? Whoops!”

“I beg your pardon?”

“Excuse me, General, the problem’s not ours anymore. Whoever’s inside is opening the hatch. See it?”

“Yes.”

The hatch cover opened very slowly. Brody watched as it swung all the way, and a ladder was rolled up. Three figures climbed out. A bit clumsy, Brody thought. Why not? They were a long time in space. Only how had they managed that? Could that be Colonel Taylor and his crew?

The astronauts wore complete space gear: full pressure suits, coveralls over that, helmets with mirrored visors dogged into place. They’d be roasting in there, Brody thought. A man sealed into a full pressure suit and disconnected from cooling air can quickly generate enough heat to cook himself to death, and there is no place for the heat to go.

A Navy flight surgeon came forward and gestured at the helmets. The astronauts nodded and reached up to the latches, began undogging the faceplates.

“Welcome aboard, gentlemen,” Admiral Jardin said.

The helmets opened. Brody’s TV screen gave a perfect view into each faceplate. His sergeant was watching intently too. He looked at the astronauts and roared with laughter. “Monkeys!” he shouted. “Holy clout, General, they caught themselves three monkeys in space suits!”

“Admiral Jardin,” Brody said quietly into the phone. His voice was the same deadly calm that Ray Hamilton had used when he alerted SAC. “Admiral—”

“Yes, General. You are seeing it. That is what you wanted to ask, isn’t it? I’m seeing it too,” the Admiral said. “No question about it, our astronauts are chimpanzees.”

“And just where the devil did they come from?” Brody demanded.

“I’ll just ask them, shall I?”

“Admiral, I have to report to the president. I do not need your jokes.”

“Sorry, Len. Well, have you any suggestions? This is a bit stranger than I’d expected. I’m at a loss.”

“Yeah. So am I. Well, the president wants an examination of that capsule made. Immediate and thorough. Meanwhile, take the—uh, the passengers somewhere secure. Someplace that knows how to take care of them. You got any labs around there? A university maybe?”

“Not secure.” Admiral Jardin was quiet for a moment. “I have a friend in the LA Zoo Commission. I expect we could get them lodged there without anybody’s knowing it. We can’t keep this secret very long, General. The whole crew of this ship knows . . .”

“Yeah. But the president decides when to break this, and to whom. Right? OK, take ’em to the zoo. That seems an appropriate place for chimps. Get somebody to examine them. Somebody with clearances.”

“You save the easy jobs for the Navy, don’t you?” Jardin said sourly.

Brody made a face at the phone. “You think you have troubles? I’ve got to report to the president. He’s going to just love this.”

THREE

Admiral George “Snapper” Jardin was not a happy man. What made things worse was that none of these problems were his own fault. His Navy people had performed flawlessly. Within minutes of the signal that an unscheduled spacecraft was going to splash down, he had a Navy interceptor fighter in the air over the predicted splash area, a rescue helicopter airborne and on the way, and a recovery carrier speeding to the scene at twenty-eight knots. The chopper crew put inflation collars around the spacecraft and kept it upright and afloat. His carrier came alongside and hoisted it aboard. Everything went fine—until the astronauts turned out to be chimpanzees. Snapper Jardin shuddered again. How did they get in the ship? “Where have we got them now?” he asked his aide.

“In the wardroom, Admiral,” Lt. Commander Hartley said. “We had them in sick bay, but there are too many things they might get hold of down there. They could hurt themselves.”

“I bet the ship’s officers like having monkeys in their wardroom. Did anybody object?”

“No, sir.” How could anyone object? Hartley wondered. They hadn’t been asked. In his experience, nobody ever asked in the Navy; the brass sent down The Word, and that was that.

“Did you get the LA Zoo?”

“Yes, sir,” Hartley said. “They’re ready. Tight security. The apes can go into the sick bay. Nothing in there right now, except a mauled fox cub, a deer with pneumonia, and a depressed gorilla who’s lost his mate. The apes will be out of sight, quarantined, and there’ll be plenty of facilities for medical and psych examinations.”

“Sounds good.” Jardin lifted the phone by the chart table. “Bridge? My compliments to the Skipper, and please take this ship into Long Beach Navy Station, standard cruising speed.” He turned back to his aide. “You found the experts yet?”

“Sir, there are a couple of animal psychologists on the UCLA staff. There’s some Army grant or other funding their work, so they’ve got clearances. They’ll start in on the apes tomorrow morning.”

“Good.” Jardin stood. “Let’s go see those apes, anyway. Has anybody fed them? There ought to be steaks aboard this ship—would they want them raw or cooked?”

“Sir, I’m told that chimpanzees are pretty much vegetarians.”

“Oh. Well, we can’t let them starve.”

“No, sir. I’ve got a sack full of oranges. One of the pilots had a supply. I thought I’d take those below.”

“Good thinking.” They walked through the ship and down two levels to the wardroom. A Marine sentry stood outside the door.

“You have them alone in there, Corporal?” Admiral Jardin demanded.

“No, sir. The surgeon’s inside with them, sir. But—”

“But what, Corporal?”

“You better look for yourself, Admiral. Them apes ain’t normal, sir. Not like any apes I ever saw.” He opened the wardroom door.

Surgeon Lt. Commander Gordon Ashmead, USNR, stood in one corner of the wardroom staring at the chimpanzees. The three apes were seated at the wardroom table. On the floor between them was a large valise.

Three full pressure suits lay stretched out on the Wardroom floor. Coveralls were hung across chairs. As the admiral entered, two of the chimps stood, exactly as a junior officer might stand when an admiral enters; the third chimpanzee struggled to close a zippered housecoat.

“Excuse me,” Admiral Jardin said. “I didn’t mean—good Lord. What am I saying?” He looked at the apes, then at Ashmead. “Good afternoon, Lieutenant Commander,” Jardin said. “I see you’ve undressed them.”

“No, sir. They took off the suits themselves.”

“Uh?” Jardin frowned. There was nothing easy about getting out of a full pressure suit. They fit like gloves, and had dozens of snaps and laces that had to be loosened. “With no help?”

“They helped each other, sir.”

“And now they’re pretending to dress,” Jardin’s aide said.

“Pretending hell,” Admiral Jardin snapped. “They are dressing. Doctor, where did they get those clothes?”

“They brought them with them, sir. In that valise.”

“Now just a bloody minute,” Jardin protested. “You’re telling me that three chimpanzees got out of a space capsule carrying a suitcase. They brought that suitcase down here, took off their pressure suits, and out of their suitcase they took clothes that fit. Then they put on the clothes.”

“Yes, sir,” Ashmead said emphatically. “That is precisely what I am telling you, Admiral.”

“I see.” Jardin looked at the three chimps. They had all resumed their seats at the wardroom table. “Do you think they understand what we’re saying, Doctor?”

Ashmead shrugged. “I doubt it, sir. They are very well trained, and chimps are the most intelligent of the animals. Except, perhaps, for dolphins. But all attempts to teach them languages have failed. They can learn signals but not syntax.”

“I don’t understand.”

“Well, sir, a dog, for instance, can understand commands. The command is a signal. When he hears it, he does something. But you can’t tell the dog to go around the block and up the stairs, then execute the command. You could train him to do it that way, of course, but you couldn’t tell him to do it. He wouldn’t understand. That would take language.”

“They sure look like they’re listening to us,” Admiral Jardin said. He turned to his aide. “Greg, give them their oranges. Maybe they’re hungry.”

“Yes, sir.” Hartley laid the bag on the wardroom table. One of the chimpanzees took it and carefully lifted out each orange. Another reached into the valise and took out a small pocket knife.

“Here now! Wait a second,” the Marine shouted. He advanced toward the chimpanzee.

“Hold it,” Dr. Ashmead said. “It’s all right, Corporal. The knife’s very short and not sharp at all. It’s the second tool they’ve employed—they used a small pick to untie a knot in one of their suit laces.”

“Um.” Admiral Jardin nodded to the Marine. “It’s all right if the Lt. Commander says it is, son. Look, you go out and arrange for an MP van to meet us at the docks, uh? We’ll want to take these critters to the zoo.”

The chimpanzee carefully peeled the first orange and passed it to another ape. She began peeling a second.

“That’s an interesting behavior pattern too, Admiral,” Ashmead said. “Usually apes won’t share. Occasionally a male will offer something to a female, and of course the big alpha males demand and get whatever they want from the smaller males, but I don’t think I’ve ever heard of a female offering a male a peeled orange.”

“She’s giving the next one away, too. Very nice manners, eh Greg?”

“Yes, sir,” Jardin’s aide said automatically. He couldn’t care less about the manners of a chimpanzee. He wanted to get back to San Diego where a blonde go-go dancer was waiting. She wouldn’t wait long. She didn’t have nice manners at all, but she had other compensations.

“Now what’s she doing?” Jardin asked. The chimpanzee had eaten the third orange, and was beginning to peel more for the others. She kept the peelings in a neat pile. “Greg, shove that wastebasket over there and see what she does, will you?”

“Yes, sir.” The chimp pushed the peelings off into the basket. One fell to the deck and she carefully leaned over to pick it up and drop it in with the rest.

“They sure are well trained, Admiral,” Dr. Ashmead said. “I’d almost think they were somebody’s house pets.”

One of the chimpanzees snorted loudly.

Admiral Jardin frowned. “Well, it’s not my problem. For all I care they could stay in the Long Beach Station Hospital—only haven’t I heard you can’t toilet train an ape? Is that right, Doctor?”

“I don’t think anybody has yet,” Ashmead answered. “Bit out of my line, though.”

“I suppose the nurses wouldn’t care for apes in their hospital,” the Admiral said.

“No, sir.”

Jardin looked at the chimpanzees and shook his head. He’d had sailors with worse manners—there were sailors on this ship with worse manners, he told himself. “Well, they’ll be happier in the zoo, anyway. They’ll even have company. I’m told there’s a gorilla in the next cage.”

The female chimpanzee slammed the pocket knife to the wardroom table.

Admiral Jardin laughed. “You’d almost think she understood me and doesn’t like gorillas, wouldn’t you?”