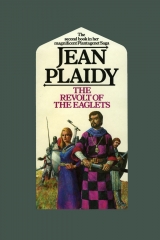

Текст книги "The Revolt of the Eaglets"

Автор книги: Jean Plaidy

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 19 (всего у книги 24 страниц)

She longed to see him and when she heard that he was considering his return to England her spirits rose. He was on his way and with him came their now heavily pregnant daughter Matilda and her husband. It was time for Eleanor to leave Salisbury.

With what joy she greeted her daughter!

Matilda was twenty-eight years old, her husband, the Duke, many years older; and now Matilda was pregnant and she told Eleanor how comforted she was to see her.

They spent much of their days together and Matilda often marvelled at the youthful looks of her mother.

‘I have spent so many years in confinement that I have been able to preserve myself,’ laughed the Queen.

‘You will see changes in the King when you see him,’ Matilda warned her.

‘Shall I see him, I wonder? He has said nothing about our meeting.’

‘He is very upset over the death of Henry.’

‘Has it changed him?’

‘The loss of a son would not change him very much. Only the loss of his crown would do that.’

‘So he shows the years?’

‘You know that he was never one to care for his appearance. I am sure he is often mistaken for the humblest of his servants for it is only on rare occasions that he pays heed to his dress.’

‘He was always so,’ said Eleanor. ‘I used to tell him that he looked like a serf.’

She wanted to hear so much of him but she had to curb her curiosity. She did not wish even Matilda to know how much she thought of him.

They sat together, Matilda embroidering a garment for her baby and Eleanor singing or playing the lute.

‘When I was in Salisbury new songs were brought to me,’ she said. ‘So much of the news came to me through them. Minstrels would sing to me of what was happening to your father and your brothers.’

Eleanor loved the children – Henry, Otto and little Matilda. She watched Matilda’s health with maternal care and herself made many of the preparations for her confinement.

What was going to happen in Saxony? she asked Matilda, but Matilda could not say. Her husband, known as Henry the Lion, had not wished to make war on Italy as the Emperor Barbarossa wanted him to and for this reason the Emperor had turned against him. The result – exile. ‘How thankful I am that we could turn to my father,’ said Matilda.

Her husband was so many years older than herself, Eleanor pointed out. Was she happy with him?

Matilda was as happy as royal princesses could expect to be, she answered.

‘Perhaps I expected too much,’ commented Eleanor. ‘I married your father for love, you know.’

‘And look where it ended,’ pointed out Matilda. ‘You were soon hating each other and all these years he has kept you a prisoner.’

‘At least it was love at the start. And although I never loved Louis, he loved me, I believe, until the day he died.’

‘But you are different from the rest of us, Mother. You guide your own fate. Ours overtakes us.’

‘And as you say I was overtaken by imprisonment in the end. Perhaps it is better to have our marriages made for us and be good docile wives. Is your Henry a good husband?’

‘He is jealous.’

‘It is often so with older men. With older women too. I was twelve years older than your father and I think that was one of the reasons which began the discord between us. He was unfaithful and I could not endure it.’

‘Yet you were unfaithful in your first marriage.’

‘That was Louis. It was different. Louis could have been unfaithful to me and I would not have cared. But perhaps I lie. I can say that, because he never would have been. No, I do not think I would have tolerated infidelity in either of my husbands, and when I discovered it in Henry that was the start of the trouble between us.’

‘My Henry was angry over Bertrand de Born,’ said Matilda. ‘He wrote love poems to me. Henry discovered and banished him from the Court.’

‘He is a great poet,’ said Eleanor. ‘He is compared with Bernard de Ventadour. I would not have his verses sung in Salisbury though, because he did much to harm your brother Richard.’

‘You know why. He fell in love with my brother Henry.’

‘I thought he was in love with you?’

‘He made verses to me but it was Henry whom he loved. If you had seen the verses he wrote to Henry you would have realised how much he loved him. He thought my brother the most beautiful creature he had ever seen and you know how these poets worship beauty. When my father had taken his castle and he stood before him, his prisoner, my father goaded him with this much flaunted cleverness and asked him what had happened to his wit now. Do you know what he replied. “The day your valiant son died I lost consciousness, wits and direction.”’

‘At which your father laughed him to scorn I doubt not.’

‘Nay, Mother, so deeply moved was he, that he restored his castle to him.’

‘He can be sentimental still about his sons,’ mused Eleanor.

‘He loved Henry dearly. Henry was always his favourite. Again and again Henry played him false and every time he forgave him and wanted to start again. He wanted Henry to love him. His death was a great blow to him.’

Eleanor played the lute and Matilda sang some of the songs which had come to Normandy from the Court of France and Aquitaine. They told of the conflict between the King’s sons and the love of knights for their ladies.

In due course Matilda’s child was born. The confinement was easy and the little boy was called William.

Eleanor, who loved little babies, delighted in caring for him.

Christmas was approaching.

To Eleanor’s amazement and secret delight, a message from the King arrived. He was summoning his sons to Westminster and he invited his wife to join them there. Matilda with her husband and children would accompany the Queen and it should be a family reunion.

The grey mists hung over Westminster on that November day, and in the palace there was an air of expectancy. This was an occasion which would be remembered by all concerned for as long as they lived. The King, the Queen and their sons would be together there.

When Eleanor came riding into the capital the people watched her in silence. This Queen had been a captive for ten years. She amazed them as she had in the days of her youth. There was something about her which could attract all eyes even now. She was an old woman but she was a beautiful one still; and the years had not robbed her of her voluptuous charm. In her gown of scarlet lined with miniver, adjusted to her special taste and with that unique talent which had stylised all her clothes, she looked magnificent.

The watchers were overawed.

Then came the King – so different from his Queen, yet, though he lacked her elegance there was about him a dignity which must impress all who beheld him. His cloak might be short and worn askew, his hair was greying and combed to hide the baldness, although by his garments he might be mistaken for a man of little significance, his bearing and demeanour proclaimed him the King.

She was waiting for him and they studied each other for some moments in silence.

By God’s eyes, he thought, she is a beautiful woman still. How well she hides her age!

The years have buffeted him, she thought gleefully. Why, Henry, you are an old man now. Where is the golden youth who took my fancy? How grey your hair is and no amount of dressing it can hide the fact that it is thinning. Does your temper still flare up? Do you suffer the same rages? Do you lie on the floor and kick the table legs? Do you bite the rushes? But what was the point in mocking? She knew that he was still the King and that men trembled before him.

He bowed to her and she inclined her head.

‘Welcome to Westminster,’ he said.

‘I thank you for your welcome and for the gifts you sent to me.’

‘It is long since we have met,’ he said. ‘Now let it be in amity.’

‘As you wish. You, my lord, now decide in what mood we meet.’

‘There must be a show of friendship between us,’ said the King. He turned away. ‘Grief has brought us together.’

They stood looking at each other and then the memory of Henry, their dead son, seemed too much for either of them to bear.

The King lowered his eyes and she saw the sadness of his face. He said: ‘Eleanor, our son …’

‘He is dead,’ she said. ‘My beautiful son is dead.’

‘My son too, Eleanor. Our son.’

She held out her hand and he took it and suddenly it was as though the years were swept away and they were lovers again as they had been at the time of Henry’s birth.

‘He was such a lovely boy,’ she said.

‘I never saw one more handsome.’

‘I cannot believe he has gone.’

‘My son, my son,’ mourned Henry. ‘For long he fought against me, but I always loved him.’

She might have said: If you had loved him you would have given him what he most wanted. He asked for lands to govern. You could have given him Normandy … or England … whichever you preferred. But no, you must keep your hands on everything. You would give nothing away. Even as she reproached him she knew she must be fair. How right he was not to have given power to the fair feckless youth.

‘We loved him, both of us,’ she said. ‘He was our son. We must pray for him, Henry. Together we must pray for him.’

‘None understands my grief,’ he said.

‘I understand it because I share it.’

They looked at each other and he lifted her hand to his lips and kissed it.

Their grief had indeed brought them together.

But not for long. They were enemies, natural enemies. Both knew the bonds must loosen. They could not go on mourning for ever for their dead son. It was not for mourning that Henry had allowed her to come. She quickly realised that. He had not released her from her prison because he wished to show some regard for her, because he had repented his harshness towards her. No, he had his motive as Henry always would.

He had brought her here for varying reasons that did not concern her comfort or well being.

In the first place she had heard through Richard that Sancho of Navarre had requested it and he wished to be on good terms with Navarre. The main reason, though, was that Henry’s death had made the reshuffle of the royal heritage necessary and he needed her acquiescence on certain points, mainly of course the re-allocation of Aquitaine.

She was overjoyed when Richard arrived at Westminster. Her eyes glowed with pride at the sight of this tall man who had the look of a hero.

They embraced each other and Richard’s eyes glowed with a tenderness rare in him.

‘Oh, my beloved son!’ cried Eleanor. ‘How long the years have been!’

‘I have thought of you constantly,’ Richard told her, and because she knew her son so well she could believe him. Her dear bold honest Richard who did not dissemble as the rest of her family did. Richard on whom she could rely; whose love and trust in her matched hers for him.

‘We must talk alone,’ she whispered to him.

‘I will see that we do,’ he replied.

He came to her bedchamber and she felt young again as she had when he was but a child and she had loved him so dearly and beyond her other children, as she still did.

‘You know why your father has brought me here?’

He nodded. ‘He wants to take Aquitaine from me and give it to John.’

‘You are the heir to the throne of England now, Richard, England, Normandy and Anjou.’

‘He has said nothing of making me his heir.’

‘There is no need for that. You are the eldest now and the rightful heir. Even he cannot go against the law.’

‘He is capable of anything.’

‘Not of this. It would never be permitted. It would plunge the country into war.’

‘He is not averse to war.’

‘You do not know him. He has always deplored war. He hates wasting the money it demands. Have you not seen that if there is a chance to evade war he will evade it? He likes to win by deceit and cunning. He has done it again and again. That, my son, is what is known as being a great king.’

‘I would never stoop to it. I would win by the sword.’

‘You are a born fighter, Richard. A man of honesty. There could not be one more unlike your father. Perhaps that is why I love you.’

‘What think you of him? He has aged, has he not?’

‘Yes, he has aged. But I remember him as a young man … a boy almost when I married him … not twenty. He was never handsome as you and Henry and Geoffrey … and even John.’

‘We get our handsome looks from you, Mother.’

‘’Tis true. Although your grandfather of Anjou was reckoned to be one of the most handsome men of his day. Geoffrey the Fair they called him.’ She smiled reminiscently. ‘I knew him well … for a time very well. A man of great charm and good looks but no great strength. Not like his son. But what has your father become now? An old man … a stout old man. He always tended to put on weight. That was why he would take his meals standing and in such a manner as to suggest he did so out of necessity rather than pleasure. Of course that unrestrained vitality of his kept down his corpulence in his youth but it was bound to catch up with him. I notice he often uses a stick when walking now.’

‘One of his horses kicked him and he has a toe nail which has turned inwards and causes him pain now and then.’

‘Poor old man!’ mocked Eleanor. ‘He should have taken better care of himself. He is never quite still. One cannot be with him long without sensing that frenzied determination to be doing something. In that he has not changed. And how untidy he is! His garments disgrace him.’

‘He never cared for them. “I am the King,” he says, “and all know it. None will fear me the more because I wear a cloak of velvet and miniver.”’

‘In the days of his love for Thomas à Becket when Thomas was his Chancellor and they went about together one would have thought Thomas the King and he the servant.’

‘Yet Thomas died and he lives on and now he proclaims that Thomas loves him even more than he did when they were young and that he keeps an eye on him in Heaven.’

‘That is like him,’ said Eleanor, not without a touch of admiration. ‘He would turn everything to his advantage. But we waste our time talking of him. We know him so well, both of us, and that is good for we are aware of the man with whom we have to deal. What of Aquitaine, Richard?’

‘I shall never give it up.’

‘You have had a troublous time there.’

‘But I have brought it to order. They think me harsh and cruel but just. I have never murdered or maimed for sport. I have meted out terrible punishments but they have always been deserved.’

She nodded. ‘In the days of my ancestors and during my own rule life was happy in Aquitaine. We were a people given to poetry and song.’

‘Poetry and song have done much to inflame the people. You know that Bertrand de Born made it possible for Henry to come against me.’

‘I know it. They loved me. They would never have harmed me. Why could they not have accepted my son, the one I chose to follow me?’

‘They never really believed that I was on your side. They hate my father and they look on me as his son, not yours. But I have won my place by my sword and I shall keep it. I would rather be Duke of Aquitaine than King of England. I shall never give up Aquitaine to John.’

‘He has made John his favourite. That is reckless of him. Do you think John will love him any more than the rest of you did?’

‘I know not. John is like him in one way. He has that violent temper.’

‘That speaks little good for him. Henry would have done well to curb his. I wonder if he has inherited his lust?’

‘I hear it is so.’

‘Let us hope that John has inherited his shrewdness too or it will go hard with him. But it is of you I wish to speak, Richard. You will be King of England when Henry dies.’

‘And Duke of Aquitaine, for I shall never give it up. And when I am King, Mother, my first concern will be for you. Before anything else, you shall be released and beside me. I swear that.’

‘God bless you, Richard. There is no need to swear. I know it will be so. There is another matter. You are no longer a boy and still unmarried. What of your bride?’

‘If you mean Alice, she is still in the King’s keeping.’

‘Still his mistress! How faithful he is to her. What has she to hold him? She’s another Rosamund, I’ll swear. You’ll not take your father’s cast-off, Richard?’

‘I will not. I am determined to tell him that he can keep his mistress and make his peace with Philip. I know not how. There could be war over this.’

‘I doubt not he would find some way out. He has the cunning of the fox and slithers out of trouble with the smoothness of a snake.’

‘Mother, I have seen a woman I would marry.’

‘And she is?’

‘The daughter of the King of Navarre. Berengaria. Her father has intimated that if I were free of Alice he would welcome the match. Berengaria is very young. She can wait a while.’

The Queen nodded. ‘Say nothing of this. We will continue to plague him over Alice. I would I knew whether he clings to her because he finds her so irresistible or whether it is because he fears what might happen if it were known he had seduced his son’s betrothed and is afraid she might betray this. Gh, Richard, this is an amusing situation. You and I stand together against his marriage with Alice. If neither of us was here he would marry her and take her dowry and the matter would be settled. I wonder if he would be faithful to her? It is possible that he might now that he is so fat and walks with a stick and has trouble with legs and feet. Morality sets in with disabilities.’

‘You hate him still, Mother.’

‘For what he has done to you and to me, yes. It could have been different, Richard. All our lives could have been different. If he had not betrayed me with other women I would have worked for him and with him. I would have made sure that my sons grew up respecting and admiring him. He has himself to blame. But perhaps that applies to us all. Oh, Richard, how good it has been to talk with each other.’

‘One day,’ said Richard, ‘we shall be together. On the very day I am King, your prison doors will be flung wide open and I shall let all men know that there is no one I hold in higher esteem than my beloved mother.’

The King announced that Christmas should be celebrated at Windsor and that the Queen should be of the party. Eleanor was delighted. It would be the first Christmas she had spent out of captivity for a good many years. She was in high spirits. It had been wonderful to see Richard again and while she mourned for Henry she must be aware of the turn in her fortunes, for Richard was to be trusted. What he promised he would do. He was Richard Yea and Nay. God bless him! He would always be his mother’s friend.

For Christmas they must forget their enmities. They must join with the revellers. There would be feasts and music and for once the King would be forced to sit down and behave as though this was a festival and that they were not on the verge of a battle.

Eleanor and he had watched each other furtively. Neither trusted the other. That was the nature of their relationship and it could not be otherwise. He was planning to rob Richard of Aquitaine and give it to John. John was going to be as well endowed as any of them. Why not? John had never taken up arms against his father as the others had. A man must have one son to love.

What an uneasy family they were. In his heart he no more believed he could trust John than he could any of the others. There they were all at the same board, and all ready to work against one another.

What strength would have been theirs if they had worked together! And there at his table was his Queen. How did she remain so young-looking and elegant? Was it through witchcraft? That would not surprise him.

How beautifully she sang – songs of her own composing. She sang of love. She should know much of that. How many lovers had she had including her uncle and a heathen Saracen? All those troubadours who had surrounded her when she kept court with him, how many had been her lovers?

And how often had he strayed from the marriage bed? So many times; there were numbers of women whose names he could not remember. Two he would cherish for ever – Rosamund and Alice.

Oh, Alice, fair Alice. A woman now. Twenty-three years of age. She had been but twelve when he had first taken her. And she had been his ever since. He had loved Rosamund and he had loved Alice – only those two had he truly loved. What it had been with Eleanor he was unsure. There had always been conflict between them. What exciting conflict though, in the beginning when no other woman had satisfied him as she had. And of course there was Aquitaine which went with her.

With Alice there would be the Vexin, that land so vital to the defence of Normandy. God in Heaven, why would not Eleanor die! She was old enough to be dead. She had lived long enough. Did she want to go on in captivity? For by God’s eyes he had seen enough of her to know that after this spell of freedom she must go straight back to her prison.

He would never again trust her to roam free. It would be foolish to give her the opportunity.

The King sent for Richard. ‘Are you determined,’ he said, ‘that you will never give up Aquitaine?’

‘I am,’ answered Richard.

‘Then go back there.’

Richard was astonished. This could surely only mean that the King had decided not to interfere with his control of the Duchy.

When he said farewell to his mother she warned him to beware of his father. His promises were not to be trusted and if he agreed now to let him keep Aquitaine he might change his mind the next week.

Richard left, assuring his mother of his devotion which would never change.

Next the King sent for his son Geoffrey.

‘You will return to Normandy,’ he said, ‘and keep peace there.’ He then proceeded to give Geoffrey more power than he had ever had before.

Eleanor was watchful. What did this mean? Was he saying that if Richard was so determined to hold on to Aquitaine he could forgo the crown of England?

What a devious mind that was! And he had never liked Richard. It occurred to the Queen that if the King could take from Richard what was his by right and give it to his other sons, he was capable of doing that. What was he planning to give to John?

Finally he sent for his son John and told him to prepare to take over his dominion of Ireland. John seized the opportunity with alacrity. He would be ready to leave in the spring.

The King then set out with the Queen and his Court for Winchester.

Winchester – the palace of many memories, second only to that of Westminster. Here he had kept Rosamund for a time when he had ceased to keep their liaison secret. Here Alice had been with him. And now Eleanor came.

She was delighted with the place; she always had been. She admired the herb garden which had recently been made and picked many of its contents which she declared were the best of their kind.

She wondered how long she would be allowed her freedom. She knew in her heart it would not last. How could it? Their interests must certainly clash. Nothing could stop her intriguing with Richard against him when the time came, and he would know it. Well, she would rather go back to her prison than allow him to think that he had subdued her, or that she would cease to demand her rights for the sake of freedom.

He had had many decorations painted on the walls of this castle. He was rather fond of allegory, and they were adorned with scenes from his life. He would want future generations to know that he was the one who had restored it and made it beautiful.

One day when she walked through the castle she came to a room and went silently in. To her amazement she saw that the King was standing there.

The light from the narrow slit of a window showed his face drawn and sad. His carelessly donned clothes, his slovenly stance, the manner in which he leaned on his stick made her feel half sorry for him while at the same time she thought: It will not be long before Richard is the King of England. My beloved son you and I will be together. And yet she was conscious of a sadness. Ever since she had known Henry she had never wished to contemplate a world without him. She could never forget the first time she had seen him – the son of her lover, for she had shared his father’s bed once or twice. Geoffrey the Fair had never been the most beloved of her admirers though he was an exceptionally good-looking man and a virile one too. But when she had seen the son, she wanted no more of the father. Henry, lover, and husband for whom she had divorced the King of France, father of their troublesome brood, the lion and the cubs who from their earliest days had planned his downfall.

He was aware of her and without taking his eyes from the walls he said: ‘’Tis you then?’

‘This room has changed since I knew it long ago.’

‘I have had it newly painted.’

‘And you admire it evidently.’

‘Come and look at this picture.’

She went and stood beside him. ‘An eagle and four eaglets,’ she said.

‘Yes. Look closer. See how the young prey on the old bird. Do you see anything familiar in their faces?’

She turned to look at him and she saw the glaze of tears in his eyes.

Henry Plantagenet in tears! It was impossible.

‘I am the eagle,’ he said. ‘The four eaglets are my sons.’

‘You have caused this picture to be painted.’

He nodded. ‘I look at it often. See how they prey upon me. My three sons, Henry, Richard and Geoffrey. And see the fourth poised on my neck. That is John. I tell you this, that he, the youngest, the one I love so tenderly, is waiting for the moment when his brothers have laid me low; then he will pluck out my eyes.’

‘I am surprised that you torment yourself with such a picture.’

‘There must be somewhere where I face the truth. I feign to believe them. I am their father. I have been over-tolerant with them. I let them deceive me and I deceive myself that they must love me because they are my own sons.’

‘You should never have put a crown on Henry’s head.’

‘I know it well.’

‘You did it to spite Thomas of Canterbury. You wanted a coronation in which he should not partake.’

‘Yes. But I did it too because I feared God might take me in battle and I wanted no bloodshed. I wished it to be that when the King died, there was a new King ready waiting.’

‘It was a foolish act.’

‘Unworthy of a shrewd king,’ he agreed. ‘And here I look at this picture and face the truth.’

‘It is not too late. Trust your sons. Take Richard to your heart. He is your heir. Give him the power he needs.’

‘That he might take my crown from me?’

‘He will not take it until it is right and proper for him to do so.’

‘The eaglets are impatient,’ he said.

‘Because the eagle has kept them in the nest too long.’

‘You turned them against me,’ he accused. ‘You are the source of all my troubles.’

‘Had you been the husband I wanted, I would have loved you to the end.’

‘You wanted to rule.’

‘Aye. We both wanted it.’

‘And between us we bred the eaglets.’

He turned away at the door and looked back at her.

‘This painting will be copied and I shall have it in my chamber at Windsor. There I shall look at it often and I shall remember.’ His voice shook slightly and he said suddenly: ‘Oh, God, Eleanor, why was it not different? What would I not give just for one loving son.’

Then he was gone. She listened to the sound of his stick on the stone flags.

She laughed quietly. Poor Henry, the great king, the seducer of women, the lover whom none could resist. He had failed where she had succeeded for she had one son who loved her.