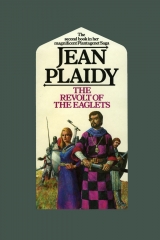

Текст книги "The Revolt of the Eaglets"

Автор книги: Jean Plaidy

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 15 (всего у книги 24 страниц)

The King was determined to bring home the lesson.

‘When my sons turned against me,’ he said, ‘they went to the King of France for aid and he gave it to them. Yet when the son of the King of France seeks to rob him of his authority, his wife the Queen asks my help. I am prepared to give it.’

‘It is noble of you, my lord,’ said young Henry.

His father burst out laughing. ‘Noble! Kings cannot afford to be noble. Kings must consider what is good for their kingdoms and if nobility is, then so much the better. If not, then that king who served his country ill in order to be noble would be a fool. Nay, I shall go to the aid of Louis and Adela, because I am determined to curtail the power of the Count of Flanders and his minion the King of France. I am going to make sure that Normandy is safe. So I will go to the aid of my erstwhile friend Louis and forget the ill service he did me when I was in like case. Your hold on the crown must be your first consideration, my son. Keep it firm. Then you will be a good king and however noble you are, consider it not.’

‘Shall we set out at once then?’

‘We shall. Alas, you will not be accompanied by your good friend, William the Marshall. You sent him back to England when you could ill afford to lose his services.’

Young Henry was silent. As usual his father succeeded in humiliating him.

When Philip of Flanders heard that the King of England had landed he took fright. This was not what he had wanted. He knew very well that he and young Philip could not stand out against that doughty warrior. Another thing he knew was that Louis’s ministers were becoming a little uneasy and that if it came to war they would not be ready to support him.

The Count cursed young Henry for going to his father; it was some sort of revenge he supposed, because he had advised him to get rid of William the Marshall. Ill luck again. He had failed to dominate young Henry and if he were not careful he would fail with Philip. Once Henry Plantagenet arrived with his armies in defence of Queen Adela and her brothers, he would find no one ready to face them with him. One thing was certain, the Count must not lose his influence over Philip.

The boy was foolishly blustering when he heard that the King of England had set sail.

‘Let him come,’ he cried. ‘He will find my armies waiting for him.’

The Count nodded but he was very uneasy. But he did see a way in which he could keep his influence over the King.

There was never any event which secured an alliance more firmly than marriage. Count Philip had often cursed the barren state of his wife but never more than at this time. If only he had a daughter whom he could marry to Philip. Then he would be the father of the Queen of France and could in truth call himself the King’s father.

He did, however, have a niece. She was only a child but then Philip was not very old.

‘Now you are indeed King of France you should have a queen,’ he suggested.

Philip considered the idea. It appealed to him.

‘My niece Isabel is a very charming girl. What would you think of such a marriage? You would have Flanders in due course and Vermandois.’

Philip said he would like to see Isabel.

‘You shall,’ said the Count.

When the meeting was arranged, Philip expressed himself agreeable to the prospect, for Isabel had been well primed by her uncle to behave in a manner to please the young King, which was of course to be overawed by him and behave as though she were in the presence of a young god.

It was not difficult then for the Count to arrange an early marriage and coronation.

Here there was a difficulty, as naturally the one to perform the ceremony should be the Archbishop of Rheims, Queen Adela’s brother, who was in the same position in France as the Archbishop of Canterbury was in England.

Count Philip found himself getting deeper into a troublesome situation. With the two Henrys of England on the march, and the people of France becoming restive, young Philip might soon begin to realise that he had not been as wise as he thought he had in placing his fate in the hands of the Count of Flanders.

The Archbishop of Sens must be made to see that it would go ill with him if he did not perform the coronation of Queen Isabel and no sooner had he done so than the Archbishop of Rheims saw his chance of breaking the influence of the Count of Flanders. The right to crown the Queen of France was his and although his sister Queen Adela and his brothers were being treated so badly, the Pope could not fail to support him over this last piece of folly.

In the midst of the upheaval caused by this matter, Henry of England arrived.

Such was the reputation of Henry Plantagenet that when he came at the head of an army terror filled the hearts of all those whom he considered his enemies.

It was therefore with great relief that Philip of Flanders received a message that the King of England wished to speak with him and Philip of France before he went into battle against them.

‘We should meet the King of England,’ said the Count.

‘Why so?’ demanded young Philip. ‘How dare he come over here threatening me! I am the King, am I not?’

‘You are, but soon might not be if Henry moved against us. Louis still lives and we have many enemies. Let us be cautious. We should certainly not go to war against Henry Plantagenet if we can help it.’

‘Young Henry is with him. I thought he was my friend and he is false … quite false.’

‘Do not think too harshly of him. He will one day be the King of England, it will be well to keep on good terms with him.’

‘My father never really trusted the King of England.’

‘Nor should you. We will meet them and outwit them, which is a cleverer way of dealing with an opponent than fighting in battle.’

But Henry refused to allow the Count of Flanders to join them. He now wished to speak to young Philip alone, he insisted, and the Count was forced to accede to the wishes of the King of England.

When the meeting took place Henry studied the young King of France. A poor creature, he thought, and could not help comparing him with his own sons. There was not one of them who was not handsome. Poor Louis! He had staked everything on this boy and what had he got? A stripling so eager for power that he was snatching the crown from his father’s head before he was dead. His own were as bad, he knew; but at least they looked like men.

And Philip of Flanders … an ambitious man! Well, he could understand that. The Count would have liked to be a king, and since he was not he was doing his best to make himself one. He would have to be watched. Henry had more respect for him than he had for the young King.

‘My lord King,’ he said kindly, ‘I would speak to you as a father. I beg of you take care how you act. Your mother is sorely distressed. Your uncles too. These people wish you well. You cannot treat them churlishly as you have been doing. This is not worthy of you.’

Young Philip glowered. Who was this man? To whom did he think he was talking?

He said: ‘The Duke of Normandy is somewhat bold.’

The King burst out laughing. ‘I come not to you as the Duke of Normandy to pay homage to my overlord, but as the King of England who is brother to the King of France and at this time sees that brother in sore need of help.’

‘I understand you not,’ replied Philip.

‘Then let me explain. My good friend King Louis of France lies on his sick bed. While he lives there can only be one King of France in fact although another – and rightly – bears the title too and when the time is ripe should take the crown. There are worthy men in your kingdom who do not care to see the Queen and her family humiliated.’

‘Is it for them to like what I do?’

‘Kings rule by the will of the people.’

‘It surprises me to hear the King of England speak so.’

‘A strong king rules his people and if he does it well, however strict his laws, if they be just the people will accept them and welcome his rule. A strong good king is respected by his people and without that respect the crown sits uneasily on his head.’

Philip lowered his eyes. He knew that he was no match for the King of England.

‘Now,’ went on Henry, ‘you should become reconciled to your mother. The people do not like to see you harsh with her. The mothers of the nation will turn against you and they may persuade their sons to do the same. You need the services of men such as your uncles. Bring them to Court. Listen to what they say. A king does not necessarily take the advice of his ministers but he listens to them.’

It was not easy for young Philip to withstand Henry’s arguments and before the interview was over he had decided to call back his mother and receive his uncles at Court.

When the Count of Flanders heard what had taken place he knew that he had lost and must temporarily retire from the field.

It was at this time that Louis’s illness took a more serious turn.

On a September night he became very ill and it was obvious that the end was not far off. Adela was with him at the end and that seemed to comfort him. Philip knelt by his bedside and wept with remorse, for now that he had been obliged to accept the return of his uncles and was friendly with his mother again he realised how rash he had been and what a bad impression he had made on his subjects by trying to take the crown while his father still lived.

As for Louis he lay back with a smile of serenity on his face.

This was the end. He was not sorry, for it had not been an easy life. Ever since he had known that his destiny was to wear the crown he had been afraid, often he had longed for the peace which he believed would have come to a man of the Church. The way had often been stormy. He would never forget the cries of men and women dying in battle. He had been haunted by them throughout his life. There had been good moments – with Eleanor in the beginning; with his children and particularly with Philip.

But it was all over.

‘My son …’ he murmured.

Philip kissed his hand.

‘God bless you, my son. A long and happy reign. Farewell, Philip, farewell France.’

Then Louis closed his eyes and died.

Chapter XIII

Chapter XIII

BERENGARIA

Side by side with his good friend Sancho, Prince of Navarre, rode Richard, Duke of Aquitaine. It was rarely that he took time off from the continual battle to hold the Dukedom, but he considered this a political mission for he had a favour to ask of the King of Navarre.

Sancho, that Prince known as the Strong, had invited him to a tournament which was being held in Pampeluna and Richard was noted for his skill in the joust; moreover, he and Prince Sancho had a good deal in common, for besides being brave warriors they were also poets.

In the court of Sancho the Wise – father of Sancho the Strong – the troubadours flourished as they did in Aquitaine. So as the two young men rode south they had much to talk of.

Richard made a fine figure on his horse, being so tall and with those blond good looks which were rare in this part of the country. Although he suffered periodically from a distressing disease known as the quartan ague he was otherwise very strong and healthy. He had picked up this ague when he was in his early teens and it was no doubt due to sleeping so often on the damp ground when in camp. His limbs would tremble and the effect was extraordinary for the fierceness of his cold blue eyes belied this trembling. It was said among his soldiers that when the ague was on him he was at his most fierce, and those who did not know him well, thinking it might be the outward sign of some inner weakness, soon learned to the contrary. There seemed to be a compulsion within him to belie the trembling. His ruthlessness increased, and he became noted for his cruelty. If a prisoner was brought before him and showed signs of believing he might take advantage of him because he was seen to tremble, that man would be condemned to have his eyes put out that he might never more look on Richard’s trembling. The people of Aquitaine were beginning to fear him, and he had not yet understood that, although they were not by nature warlike and their love of soft living and poetry and song was their main characteristic, they were not of a nature to accept tyranny; and resentment, fanned by the verses of their poets, was smouldering and ready to burst into flame. There was trouble brewing in Aquitaine. The people did not want this Norseman to rule them – for although his mother might be their own Eleanor and his father the son of Geoffrey of Anjou on his mother’s side he was descended from the Conqueror and those barbarians who had sailed from the Northern lands to pillage and conquer.

Richard himself knew that the only way to establish peace in Aquitaine was to bring back his mother. She was their Duchess. In their eyes her marriage to Henry Plantagenet had been a disaster. She had made him their Duke, a fact which they had never accepted; and borne sons – such as Richard – who brought to Aquitaine a way of life which was unacceptable.

There would be no end to conflict; and because he realised this, he had decided to accept this invitation to Pampeluna, that he might get away to think more clearly of the situation which faced him.

As they rode side by side, their followers behind them, they sang, often songs of their own composition. Sancho’s songs glowed with the warmth of the South; but those who listened detected as others had before them, a hint of the North in Richard’s songs. Those of the South were languorous, those of the North filled with vigour.

Even those closest to Richard thought: He is not one of us.

When they came into Pampeluna travellers were already arriving for the tournament which was to take place in a large meadow outside the castle walls. The inns were overflowing; beggars stood by the wayside, pathetic and cunning; thieves and vagabonds mingled with the respectable citizens, all looking for a picking. Stalls had been set up on which were all kinds of wares: girdles and buckles, purses, laces, brooches, razors, dice, rasps for scratching itchy skin, otter skins for making pelisses, and furs made into garments, pestles, wine, wool, barley – in fact goods of all kinds were laid out for show.

People stood in awe as the cavalcade passed. They gazed at their handsome Prince Sancho and they felt a little apprehensive at the sight of Richard of Aquitaine. There was something repelling about him, while yet fascinating. He was so tall; they rarely saw such a tall man in these parts and he sat his horse as though he and the animal were one – some strange being from Heaven or hell. His reputation had travelled ahead of him. Richard, son of Henry Plantagenet and Eleanor of Aquitaine, a man who had set the whole of his Duchy up in arms, a man who sought to subdue them by terror.

There had been many rumours. He was as great a fighter as his father and his father was a great-grandson of the mighty Conqueror whose name continued to reverberate through the land even though it was years since he had died. It was said of Henry Plantagenet that he had many sons. There were four born of Eleanor and many more he had got of other women. Rumour had it that they were not indeed sons of the Plantagenet but of the Devil. To see this tall man with the hair which was not exactly red nor yellow but somewhere in between and the eyes that were blue and cold as ice was to believe there could be some truth in the story.

It was said that when he sacked a town he took the women and indulged in debauchery and when he had had enough of them he turned them over to his men. It was hard to believe this of the cold-looking man and it was well known that a man’s enemies would tell any tale to discredit him. That he was cruel they could well believe.

The women smiled at Sancho warmly. How different was their handsome young Prince! It was true he seemed insignificant beside the other, but they loved him all the more for that. He was Sancho the Strong, who had excelled in battle and gave them such pleasure in the joust.

‘Long live Sancho the Strong,’ they cried.

The King of Navarre greeted Richard warmly. It delighted him, he said, to have the son of King Henry and Queen Eleanor at his Court. His son Sancho had told him often of Richard’s talents and he had wanted to meet him.

The tournament would begin on the following day and he trusted that Richard would add to the pleasure of the spectators by taking part in it. Richard declared his intention of doing so.

‘This night,’ said the King, ‘we shall feast in the hall and later I hope you and your attendants will enchant us with some of the melodies for which you are renowned.’

Richard replied that he was eager to hear the songs of Navarre which he was assured equalled in charm and beauty those of Aquitaine.

‘You shall be our judge,’ said Sancho. ‘My son and my two daughters shall sing for you.’

Sancho, King of Navarre, was by descent Spanish, his ancestor being the Emperor of Spain. He had married Beatrice who was the daughter of King Alphonso of Castille. He was extremely proud of his family – his beautiful wife, his son named after him who already had a reputation for valour and had earned the soubriquet of ‘The Strong’, and his two lovely daughters Berengaria and Blanche.

Richard as guest of honour sat on the King’s right hand and next to Richard sat the King’s daughter, Berengaria. She was very young, dainty and with a promise of beauty.

They feasted and drank while Richard watched the lovely young girl at his side. She was a child in truth but her intelligence astonished him and later when she sang he was enchanted by her and found it difficult to withdraw his gaze from her.

Her father, watching, was aware of this and he thought that if Richard were not betrothed to Alice of France there might have been a match between them.

Richard sang songs of love and war and somehow it seemed he sang of war more frequently than he did of love. Sancho the younger was different. This hero who had distinguished himself in battle against the warlike Moors made all aware by the trembling passion of his songs that he was also a lover.

The King remained at Richard’s side and he told him that he knew of the state of affairs in Aquitaine and was sorry for them.

‘The people want your mother back. There is no doubt of that.’

‘I know it well,’ replied Richard. ‘I would to God my father would see the reason of this.’

‘It seems so unnatural … a husband to make a prisoner of his wife.’

‘My father can be a most unnatural man.’ There was a venom in Richard’s voice which startled Sancho. It was true then, he supposed, that the sons of the King of England hated him. He looked at his own handsome Sancho and his lovely daughters and thanked God.

‘Yet if he realised that the people of Aquitaine will never settle while she remains a prisoner, it might be that he would see the wisdom of releasing her.’

‘They hate each other,’ said Richard. ‘They have for years. I was aware of it in my nursery. He brought his bastard in to be brought up with us. It was something my mother’s pride would not stomach.’

‘That is understandable.’

‘Indeed it is. When they married my mother’s position was higher than his. Then he became King of England. She would have been beside him to help him … but he spoilt that … with his lechery she used to say. I used to listen to them, taunting each other.’

‘You love your mother dearly, I believe.’

‘I would do a great deal to bring about her release. I plan to reduce my father to such a state that he will have to listen to my terms and the first of these shall be the freedom of my mother.’

Sancho nodded sympathetically but he thought: You would never bring Henry Plantagenet to his knees.

‘At this time it might be better to persuade him what her release would do for Aquitaine.’

‘I have done this. He will not listen. He sees me as my mother’s partisan and he believes that she is only capable of treachery towards him.’

‘Perhaps if another were to put the case to him.’

Richard’s heart leaped with joy. It was for this he had come to Navarre.

‘You mean … you would?’

‘I mean I could try.’

‘By God’s teeth, he would listen to you.’

‘Then let me try. I will send a message to him. I will tell him that as an outside observer I see how matters stand in Aquitaine and that the people there will never be at peace while the Duchess is a prisoner.’

‘If you could do this, you would be of great service to me and to Aquitaine.’

Sancho the Wise said: ‘Then I shall do my best.’

That night Richard exchanged tokens with young Sancho and took the oaths of chivalry with him. From this time on they would be fratres jurati, sworn brothers.

On the dais beside her father, young Berengaria sat watching the brilliant array in the meadow before her. The trumpets sounded, the gay pennants fluttered in the wind, and her heart beat fast with the excitement of watching for one particular knight. She would know him at once, even though according to practice his visor would be down. There was no one among the company so tall and straight, who sat his horse with such distinction, no one but this most perfect of all knights.

She had told Blanche that she had never seen anyone to compare with him. Blanche agreed that he was indeed a handsome knight. He was so different from all the men they had ever seen, most of whom were dark-haired, dark-skinned and of smaller stature. But Richard, Duke of Aquitaine, was of a different race it seemed.

So had the gods looked, Berengaria believed – those who had once inhabited the earth.

She glanced at her father; he was in his jewelled crown today, for it was such a great occasion. He would not ride into the lists. Her brother would do that for the honour of the crown. She hoped Sancho would not tilt against Richard for then she would be torn as to whom she must pray for, and hope to be the conqueror.

‘They will not,’ she whispered to Blanche, for she had spoken her thoughts aloud. ‘They are sworn brothers. So they would not tilt against each other on this day.’

‘’Tis not a battle,’ replied Blanche. ‘Only a tournament.’

‘Yet they will not,’ said Berengaria.

What a glorious day with a cloudless blue sky and a dazzling sun shining down on the colourful scene! How the armour of those gallant knights glittered and how the eyes of every lady shone as they rested on the knight who wore her colours, proclaiming to the world that she was his lady and his valiant deeds that day were done in honour of her.

What excitement when the first of the matches was heralded and the contestants rode into the lists. They seemed to be clad in silver and how gay were the colours of the ladies’ dresses as they sat gracefully on their dais, their eyes never leaving the colourful field stretched out before them!

And there he was – outstanding as she had known he would be – different from all the others because he was so tall. She was sure his armour shone more brightly than the rest.

She felt faint with joy, for upon his helm he wore a small glove with a jewelled border. She knew that glove well for it belonged to her.

What ecstasy! This wonderful godlike creature had this day taken the field in honour of her!

Of course he was victorious. It would have been embarrassing if he were not, since he was their guest of honour. But there need have been no fear of that. He was more bold, more skilled, more daring in every way.

He rode to the dais where the King sat with his wife and two daughters. He bowed on his horse, and Berengaria took one of the roses which adorned the balcony and threw it to him. He caught it deftly, kissed it and held it against his heart.

It was a charming knightly gesture; and from that moment Berengaria of Navarre was in love with Richard of Aquitaine.

He could not tarry long in Navarre. His absence would give his enemies the opportunities they sought. Yet he was attracted by Berengaria. She was but a child but she would grow up. He had no wish for marriage yet. He could wait. She adored him and thought of him as some superior being. That was pleasant.

He talked to her as they sat side by side at table of the beauties of Aquitaine; he told her of his growing desire to go on a crusade to drive the Infidel out of the Holy Land.

She listened, hands clasped, eyes shining. He was certain that if he married her while she was so young and innocent he could make her into the wife he wanted.

He talked to her father.

‘You have two beautiful daughters,’ he said, ‘and in particular the eldest. I would I were in a position to ask you for her hand.’

‘If you were to do so I should not deny you,’ answered Sancho.

‘You know my position. For years I have been betrothed to the daughter of the King of France.’

‘I know this. But the marriage has been long delayed.’

‘My father said it was to take place. But I have heard no more since.’

‘You wish for this marriage?’

‘Not since I have seen your daughter.’

‘Since there has been this delay, your father must have some reason for it.’

‘My mother says that he has and that it plagues him when there is insistence on its taking place.’

‘Do you think it would please him to forgo an alliance with France for the sake of one with Navarre?’

‘We have alliances with France. My elder brother is married to the daughter of a King of France.’

‘You are in a very strange position, but I am honoured that you should admire my daughter.’

Sancho was thoughtful. He was not called ‘The Wise’ for nothing.

At length he said: ‘As yet let us say nothing of the attraction you feel for my daughter. The Princess Alice has been long withheld from you. Why should you not if she should be offered withhold yourself from her? Excuses have been offered to you. Why then should you not offer excuses? If you do not wish to marry the Princess Alice you can avoid it.’

‘I will do that and in time …’

‘Berengaria is young yet … too young. Perhaps in due course …’

Richard thanked Sancho fervently.

‘I will wait,’ he said. ‘And in the meantime you will speak to my father … not of a possible marriage but of my mother’s imprisonment?’

‘This I will do,’ said Sancho. ‘I give you my word on it.’

Richard strummed his lute. Berengaria sat beside him, her eyes shining.

The song was of love and although it held the northern strain it throbbed with passion.

‘I will return,’ said Richard. ‘I shall find you here … waiting.’

He laid down his lute and smiled at her.

‘You are but a child, Berengaria.’

‘I shall soon grow up.’

‘Then we shall meet again.’

‘You will not forget me?’

‘Never will I forget you. I shall return and will you be waiting?’

‘Yes,’ she answered, ‘until I die.’

‘Long before we die we shall be together.’

‘Richard, I have heard that you are betrothed to a French Princess. Is it true?’

‘I was betrothed to her in my cradle.’

‘She is very beautiful, I have heard. Do you find her so?’

‘I cannot find her beautiful for I know not what she looks like. Although we were betrothed she has been withheld from me.’

‘Does that cause you sorrow?’

‘Now it causes me nothing but joy.’

‘What if your father arranges a marriage for you?’

‘It will not be the first time he has found me a disobedient son.’

‘You will in truth refuse to marry her?’

He smiled and nodded. ‘There is only one whom I would marry.’

‘And who is she?’

‘Her name is Berengaria and she lives at her father’s court of Navarre.’

‘Can it really be so?’

He took her hand and kissed it.

‘Does my father know?’

‘We have spoken of this.’

‘And what says he?’

‘That when you are of an age and I am free of my entanglements it could come about.’

‘I am so happy,’ she said.

He pressed her hand and took up his lute again.

When he rode away she was at the turret watching him.

‘His coming has changed my life,’ she told Blanche. ‘I shall pray for the day when we can be together.’

He turned and waved a piece of silk – a scrap from one of her gowns. He knew she would be watching.

‘Soon he must come back,’ she whispered.