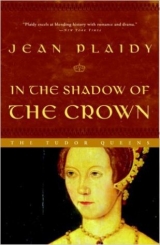

Текст книги "In the Shadow of the Crown "

Автор книги: Jean Plaidy

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 15 (всего у книги 33 страниц)

How could I have been so blind as to rejoice because Philip of Bavaria was a young and presentable man… when he was a heretic?

I could not marry him. Yet it might be that I must. I prayed. I called on my mother in Heaven to help me. But what could I do? If my father—and Cromwell—desired this marriage, I was powerless to prevent it.

My dream of possible happiness was fading away. I was weak. I was helpless—and I was about to be married to a heretic. I did think about him a good deal. I had wanted this marriage…I was tired of spinsterhood. I had dreams of converting him to the true Faith. I encouraged that dream because I wanted to marry, and it was only with such a project in mind that I could do so with a good conscience.

ON THE 27TH of December Anne of Cleves left Calais to sail for England. When she landed at Deal, she was taken to Walmer Castle and, after a rest there, she proceeded to Dover Castle where, because the weather was bitterly cold and the winds were of gale force, she stayed for three days. Then she set out for Canterbury, where she was met by a company of the greatest nobles in the land, including the Duke of Norfolk. She must have been gratified by the warmth of her welcome and perhaps looked forward with great pleasure to meeting the man who was to be her husband.

Poor Anne! When I grew to know her, I felt sorry for her; and I often pondered on the unhappiness my father brought to all the women who were close to him.

He forgot that he was ageing, that he was no longer the romantic lover. He was excited. Pretending to be young again, going forth to meet the lady of Holbein's miniature and to sweep her off her feet with his passionate courtship. He had brought a gift for his bride: the finest sables in the kingdom to be made into a muff or a tippet.

It was at Rochester where they met. Unable to curb his impatience any longer, my father rode out to meet her cavalcade. He sent his Master of Horse, Anthony Browne, on ahead to tell Anne that he was there and wanted to give her a New Year's present.

I wished that I had seen that first meeting. I will say this in his favor. He did not convey to her immediately his complete and utter disappointment. He curbed his anger and made a show of courtesy. But she must have known. She was never a fool.

I did hear that, when he left her, he gave vent to his anger. There were plenty who heard it and were ready to report it. He was utterly shocked. The woman he saw was not in the least like Holbein's miniature, he complained. Where was that rose-tinted skin? Hers was pitted with smallpox scars. She was big, and he did not like big women. She was supposed to be twenty-four, but she looked more like thirty. Her features were heavy, and she was without that alluring femininity which so appealed to his nature.

He did not stay long with her. It would have been too much to keep up the pretense of welcome when all the time he wanted to shout out his disappointment.

Lord Russell, who witnessed the scene, said he had never seen anyone so astonished and abashed. As soon as he left her, his face turned purple with rage and he mumbled that he had never seen a lady so unlike what had been represented to him. “I see nothing… nothing of what has been shown to me in her picture. I am ashamed that I have been so deceived and I love her not.”

He could not bring himself to give her the sables personally but, as he had mentioned a New Year's gift, he sent Sir Anthony Browne to give them to her.

Meanwhile he raged against all those who had deceived him. She was ugly; her very talk grated on his ears. He would never speak Dutch—and she had no English. They had brought him a great Flanders mare.

I wondered what she thought of him. His manners might have been courtly enough during that brief meeting; his voice was musical, though of a high pitch. But he was now overweight, lame and ageing; though he still had a certain charm; and he would always retain that aura of royal dignity.

It is well known now how my father tried to extricate himself, how he sought to prove that Anne had a pre-contract with the Duke of Lorraine and was therefore not free to marry.

Nothing could be proved. Anne swore that there had been no precontract. Glaring at Cromwell as though he would like to kill him, the King said, “Is there none other remedy that I must needs, against my will, put my neck in this yoke?”

A few days after Anne's arrival, my father invested Philip of Bavaria with the Order of the Garter. It was a moving ceremony, and Philip looked very handsome and dignified. I was proud of him. People commented on his good looks and his reputation for bravery. I was learning more about him. He was called “Philip the Warlike” because he had defended his country some years before against the Turk and scored a great victory. And…I was liking him more every day.

There were many opportunities of meeting him, and Margaret Bryan said I was fortunate. It was not many royal princesses who had the blessing to fall in love with their husband before their marriage.

Margaret was now looking after Edward and, as she had Elizabeth with her, she was happy. Moreover, my position had improved so considerably that she no longer felt the anxieties she once had with her charges.

How I wished that the Countess could be with me! I should have loved to visit her in the Tower and take some comforts to her, but that of course was out of the question. I could not get news of her, much as I tried. She was constantly in my thoughts though.

Young Edward's household was at this time at Havering-atte-Bower. He was quite a serious little boy, already showing an interest in books. He adored Elizabeth, who was so different from himself. Full of vitality, she was so merry and constantly dancing; she was imperious and demanded Edward's attention, which he gave willingly.

“You should see his little face light up when his sister comes in,” said Margaret fondly.

I did see what she meant. There was that quality about Elizabeth.

I was happy to be part of this family, scattered as it was, and living, as I often thought, on the edge of disaster. Neither Elizabeth nor I knew when we would be in or out of favor.

The New Year was a pleasant one, apart from those recurring memories of the Countess and a slight apprehension about my prospective bridegroom and his heresy… though I had to admit that, so charming was he, I was lulling myself into an acceptance of that. I would convert him to the true Faith, I promised myself, which helped me indulge in daydreams of what marriage with him would be like.

I enjoyed being with the family that Christmas and New Year.

Elizabeth was always short of clothes, and Margaret was in a state of resentment about this; she was constantly asking for garments for her and grew very angry when there was no response. So, for a New Year's gift, I gave the child a yellow satin kirtle. It had been rather costly but I was glad I had not stinted in any way when I saw how delighted she was. I have never known anyone express her feelings so openly as Elizabeth did. Her joy was spontaneous. She held the kirtle up to her small body and danced round the room with it. Edward watched her and clapped his hands; and Margaret fell into a chair laughing.

For Edward I had a crimson satin coat, embroidered with gold thread and pearls. He was just past two at this time and a rather solemn child, completely overpowered by Elizabeth. Elizabeth declared the coat was magnificent. She made him put it on and, taking his hands, danced with him round the chamber.

Margaret watched with some apprehension. Everyone was perpetually worried that Edward might exert himself too much. If he had a slight cold they were all in a panic. They feared the King's wrath if anything should happen to this precious child.

Elizabeth was very interested to hear about the new Queen.

“I want to meet her,” she said. “She is, after all, my stepmother, is she not? I should meet her.”

I often wondered how much she knew. She was only a child—not seven years old yet; but there was something very mature beneath the gaiety– watchful almost. She was certainly no ordinary six-year-old.

When I was alone with Margaret, she told me that Elizabeth had begged her to ask her father's permission to see the new Queen. The King had replied that the Queen was so different from her own mother that she ought not to wish to see her; but she might write to Her Majesty.

And had she done this? I asked Margaret.

“She never misses an opportunity. I have the letter here but I have not sent it yet. I suppose it is all right to send it as she has the King's permission; but I should like you to see it and consider that it is the work of a child not yet seven years old.”

She produced the letter.

“Madam,” Elizabeth had written, “I am struggling between two contending wishes—one, my impatient desire to see Your Majesty, the other that of rendering the obedience I owe to the King, my father, which prevents me from leaving my house until he has given me permission to do so. But I hope that I shall shortly be able to gratify both these desires. In the meantime, I entreat Your Majesty to permit me to show, by this billet, the zeal with which I devote my respect to you as my Queen, and my entire obedience to you as my mother. I am too young and too feeble to have power to do more than felicitate you with all my heart in this commencement of your marriage. I hope that Your Majesty will have as much good will for me as I have zeal for your service…”

It was hard to believe that one so young could have written such a letter.

“Surely someone helped her,” I said.

“No…no…it is not so. She would be too impatient. She thinks she knows best.”

I marvelled with Lady Bryan but she told me that she had ceased to be surprised at Elizabeth's cleverness.

Later, when they did meet, Anne was completely charmed. I daresay she had been eager to meet the six-year-old writer of that letter. Her affection for the child was immediate, and she told me that if the Princess Elizabeth had been her daughter, it would have given her greater happiness than being Queen. Of course, being Queen brought her little happiness, but she did mean that she had a very special feeling for Elizabeth, and as soon as she was acknowledged as my father's wife she had the girl seated opposite her at table and accompanying her at all the entertainments.

It was decreed that I should spend some time with her. I was to talk to her in English and try to instruct her in that language. I should acquaint her with our customs. This I did and came to know her very well; I grew fond of her and, during that time when she was wondering what would become of her, because it was quite clear that she did not please the King, having suffered myself, I could sympathize with her.

I was wondering whether my father would actually marry her. But there was no way out. It had been proved that Anne had entered into no contract with any man and therefore was perfectly free. My father's three previous wives were all dead. There was no impediment.

My father must have been the most reluctant bridegroom in the world. He said to Cromwell just before the ceremony, “My lord, if it were not to satisfy the world and my realm, I would not do what I have to do this day for any earthly thing.”

Words which boded no good to Cromwell, who had been responsible for getting him into this situation—nor to his poor Queen, who was the victim of it.

I was present at the wedding. My father looked splendid in his satin coat, puffed and embroidered and with its clasp of enormous diamonds; and he had a jeweled collar about his neck. But even the jewels could not distract from his gloomy countenance.

Anne was equally splendid in cloth of gold embroidered with pearls; her long flaxen hair was loose about her shoulders.

And so the marriage was celebrated.

There was feasting afterward. I soon learned that the marriage had not been consummated. It was common knowledge, for the King made no secret of it. In his own words, he had no heart for it, and he was already looking for means of ridding himself of Anne.

Because I was close to her at that time, I knew of her anxieties. The King was no longer trying to hide the revulsion she aroused in him. She was quite different from all his other wives. She was not learned like my mother; she was not witty and clever like Anne; she was not pretty and docile like Jane.

I sensed the speculation in the air. What did he do with wives when he wanted to be rid of them? Would he dare submit her to the axe? On what pretext? He was adept at finding reasons for his actions. Was her brother, the Duke of Cleves, powerful enough to protect her? Hardly, when the Emperor Charles had not been able to save his aunt.

I knew what it felt like to live under the threat of the axe. I myself had done so for a number of years. We were none of us safe in these times.

When we sat together over our needlework, she would ask me questions about the King's previous wives. I talked to her a little about my mother, and it was amazing to me that there could be such sympathy between us, because she was a Lutheran; yet this made little difference to our friendship.

I think she was most interested in my mother and Anne Boleyn—the two discarded wives. Jane had not reigned long enough for her to meet disaster; and she had been the only one to produce a son. I knew what was in her mind. The King wanted to be rid of her, and we had examples of what he did with unwanted wives.

At times there was a placidity about her, as though she were prepared for some fearful fate and would accept it stoically; at others I glimpsed terror.

There was something else I noticed. It was at table. There was a young girl there—very pretty, with laughing eyes and a certain provocative way with her, and the King often had his eyes on her.

I asked one of the women who she was.

“She's the old Duchess of Norfolk's granddaughter, Catharine Howard.”

“She is very attractive.”

“Yes…in a way,” said the other.

I thought if she was related to the Howards she must be a connection of Anne Boleyn. There was something about these Howard women.

I put the matter out of my mind. After all, the King had always had an eye for a certain type of woman.

I did not realize then how great was my father's passion for this girl. She was small, young and childlike—very pretty in a sensuous way, with doe-like eyes and masses of curly hair. There was a look of expectancy about her, a certain promise, which I understood later when I learned something of what her life had been.

As for Anne of Cleves, she had none of that quality about her at all; she was pleasant-looking; she was tall, of course, and perhaps a little ungainly; her features were a trifle heavy, but her eyes were a beautiful brown, and I thought her flaxen hair charming.

However, my father would have none of her, and his growing passion for Catharine Howard made him determined to be rid of her.

They were uneasy days. Philip had gone back to Bavaria after taking a loving farewell and telling me we should soon be together. I was sorry to see him go. I had liked to have him near me. I had had so little of that attention he bestowed on me, and it made me feel attractive and desirable like other women; and as one day I planned to convert him back to the true Faith, I was able to still my conscience about his religious views.

Cromwell was created Earl of Essex in April. I wondered why, for my father was blaming him more and more for his marriage.

Politics were changing, too. Chapuys told me with some amusement that my father's interest in the German princes was waning, and he was veering now toward the Emperor. My cousin was a man of whom my father was afraid more than of anyone else—and with good reason, too. Charles was proving himself to be the most astute monarch in Europe; his power was increasing, and it was not good to be on bad terms with him. My mother being dead meant that there was no great reason for contention between them. I was being treated with a certain respect, so there was no quarrel on that score. Of course, the Emperor would not approve of my betrothal to Philip of Bavaria any more than he had liked the alliance with Cleves, but my father did not like it either—so he and the Emperor were in agreement about that.

Who had forged the German alliance? Cromwell. Who had brought the King a bride he disliked? The same.

The King had never liked Cromwell, and, like Wolsey's, Cromwell's swift rise from humble origins had angered many at Court; moreover, Cromwell's enemies were as numerous as those who had helped Wolsey to his fall.

There were two things my father ardently desired: to rid himself first of all of his wife, and secondly of Cromwell And those who looked for favors would help him to attain both those ends.

The alliance with the petty German princes had been a mistake; and Cromwell had made that mistake. He had, it was said, received bribes; he had given out commissions without the King's knowledge; he had trafficked in heretical books. There was rumor that he had considered marrying me and setting himself up as king, an idea which shocked me considerably, even though I did not, for one moment, believe it.

He was tried, and as all those present knew what verdict the King wanted, they gave it.

I was horrified. Whatever else Cromwell had done, he had worked well for the King. It appalled me that he could have come to this. I knew that Cromwell's vital mistake was to have arranged the marriage with Anne of Cleves. But was it his fault that her physical appearance did not please the King?

I felt sorry for the man…to have risen so high and to fall so low. There was only one to say a good word for him and that was Cranmer. Cranmer, though, was not a bold man. He asked the King for leniency but was abruptly told to be silent, and immediately he obeyed.

Cromwell languished in prison, not knowing whether he would be beheaded or burned at the stake. He did implore the King to have mercy, but my father was intent on one thing, and that was to bring his marriage to Anne of Cleves to an end.

Norfolk was sent to visit Cromwell in the Tower, and there Cromwell revealed to him the content of several conversations he had had with the King disclosing intimate details of the latter's relationship with Anne of Cleves which made it clear that the marriage had not been consummated.

As a result it was declared null and void.

I was with Anne at Richmond when the deputation arrived. She went to the window and saw Norfolk at the head of it. She turned very pale.

“They have come for me,” she said. “They have come as they came for Anne Boleyn.”

I stood beside her, watching the deputation disembark at the stairs and come toward the palace.

“You should leave me,” she said.

I took her hand and pressed it firmly. “I will stay with you,” I told her.

“No, no. It is better not. They would not allow it … Better to leave me.”

I knew her thoughts. She was seeing herself walking out to Tower Green as her namesake had gone before her. She must have thought during the last months of this possibility, and she had considered it with a certain calm, but when it was close… seeming almost inevitable, she felt, I believe, that she was looking death straight in the face.

I could see that my presence distracted her. So I kissed her gently and left.

I learned that when the deputation was presented to her, she fainted.

THEY HAD GONE.

I went to her apartments. I had already heard of the faint and was surprised when she greeted me with exuberance.

“I am thanking God,” she said.

“But you were ill…”

“I am well now. I am no longer the Queen.”

I stared at her, as she began to laugh.

“I …” she spluttered. “I am the King's sister!”

I could see that she needed to recover from the shock she had suffered when the deputation had arrived, for she had been sure they had come to conduct her to the Tower. But no… they had come to tell her that she was no longer the King's wife. In future she would be known as his sister.

“How can this be?” I asked.

“With the King,” she said, still hovering between laughter and tears, “they do anything he wishes. I was his queen and now he has made me his sister. How can that be? you ask me. It can be because he says it is so.”

“And you…you are safe.”

She gripped my hands, and I knew how great her fear had been.

“I am no longer the King's wife,” she said soberly. “And that is something to be very happy about. Ah, I must be careful. They would call that treason. But you will not betray me, dear Mary.”

“Be calm, Anne,” I said. “You have been so wonderfully calm till now.”

“It is the relief,” she replied. “I did not know how much I wanted to live. Think of it! I am free. I do not have to try to please him. I wear what I like. I am myself. I am his sister. He is no longer my husband. Can you imagine what that is like?”

“Yes,” I told her. “I believe I can.”

“That poor woman… think of her…in her prison in the Tower, waiting for the summons… waiting for death… she was Anne…as I am. I know what it is like.”

“I understand, too.”

“Then you rejoice with me.”

“I rejoice,” I told her.

“I am to have a residence of my own and £3,000 a year. Think of that.”

“And he has agreed to this?”

“Yes…yes…to be rid of me. If only he knew how I longed for him to be rid of me. Three thousand a year to live my own life. Oh, I am drunk on happiness. He is no longer my husband. There is a condition. I am not to leave England.” She laughed loudly. “Well if I tell you the truth, my dear Mary, it is that I do not want to leave England.”

“Shall you be content to stay here always?”

“I think so.”

“He does not want you to go out of England for fear you marry some foreign prince who will say you are Queen of England and have a right to the throne.”

She laughed again. “I am happy here. I have my little family … my sweet Elizabeth and you, dear Mary. To be a mother to you, Elizabeth and the little boy… that is to me greater happiness than to be a queen.”

I never saw a woman so content to be rid of a husband as Anne of Cleves was. My father was at first delighted by her mild acceptance of her state, but later he began to feel a little piqued at her enjoyment of her new role. How-ever, by this time he was so enamored of Catharine Howard that he could not give much thought to Anne of Cleves.

The alliance with the German princes was at an end; and that meant that there was no question of a betrothal to Philip of Bavaria.

THE YEAR 1540 was a terrible one for death. My father was filled with rage against those who defied him. He was probably worried now and then about the enormity of what he had done; it was not only that he had denied the Pope's supremacy and set himself up in his place in England; he had suppressed the monasteries and taken their wealth. His rule became more despotic and those about him obeyed without question, anticipated his desires and did everything possible to avoid offending him. But it was different with the people; and when those men who called themselves holy had the effrontery to deny him and to suggest that he was not the head of his own country's Church, his rage overflowed.

He wanted vengeance and would have it. Respected men were submitted to humiliating and barbarous torture on the scaffold, men who, the people knew, had led blameless lives, like Robert Barnes the divine and Thomas Abell, were submitted to this horrible death with many others.

I thought of these things and shuddered. My father had indeed changed. Where was the merry monarch now? He was irritable, and the pain in his leg sometimes sent him into maddened rages.

When I heard that Dr. Featherstone had been treated in the same manner, I was deeply distressed and I was glad that my mother was not alive, for she would have been very distressed if she knew what was happening to her old chaplain. He had taught me when I was a child, and I could well remember his quiet kindliness and his pleasure when I learned my lessons. I could not bear to think of such a man being submitted to that torture. And all because he had refused to take the Oath of Supremacy. How I admired those brave men, and how I deplored the fact that it was my father who murdered them.

People were burned at the stake in such numbers that in the streets of London one could not escape from the smell of martyrs' flesh and the sight of martyrs' bodies hanging in chains to feed the carrion crows.

Rebellion was at the heart of it. My father had broken with Rome but that did not mean he was no longer a Catholic. The old religion remained; the only difference was that he was head of the Church instead of the Pope. He wanted no Lutheran doctrines introduced into England. People must watch their steps … particularly those in vulnerable positions. I was one of those.

Cromwell lost his head on the very day my father married Catharine Howard; that changed him for a while. How he doted on the child…she was little more. They looked incongruous side by side—this ageing man with the purple complexion and the bloodshot eyes, fleshy and irascible, biting his lips till the blood came when the fistula in his leg pained him. And she … that dainty little creature with her wide-eyed innocence which seemed somehow knowledgeable, with her curls springing and feet dancing, a child in her teens… and yet not a child, a creature of overwhelming allure for an ageing, disappointed man.

But he was disappointed no longer; he was rejuvenated; he had regained something of his old physical energy: he was dotingly, besottedly in love.

I felt sickened by it. I remembered his treatment of my mother and Anne of Cleves; to those two worthy women he had behaved with the utmost cruelty, and yet, here he was, like a young lover, unable to take his eyes from this pretty, frivolous little creature whose doe's eyes had secrets behind them.

A horrifying incident happened that year. I shall never forget my feelings when I heard. Susan, whom, happily, I had been able to keep with me, came to me one day. I guessed she had something terrible to tell me and was hesitating as to whether it would be better to do so or keep me in the dark.

I prevailed on her to tell me. I think I knew beforehand whom it must concern because she looked so tragic.

“My lady,” she said when I insisted, “you must prepare yourself for a shock.” She looked at me with great compassion.

I stared at her, and then my lips formed the words, “The…Countess… what of the Countess?”

She was silent. I tried to calm myself.

She said, “It had to come. It is a wonder it did not come before.”

“Tell me,” I begged.

“She is dead…is she not?” “She had been suffering all these months in the Tower. She was wretched there. It is best for her. Cold, miserable, lacking comfort. Heartbroken… grieving for her sons…”

“If only I could have gone to her.”

Susan shook her head. “There was nothing you could have done.”

“Only pray for her,” I said.

“And that you did.”

“I always mentioned her in my prayers. Why… why? What had she done? She was innocent of treason.”

“That insurrection of Sir John Neville… such things upset the King.”

“I know. He wants the people to love him.”

“Love must be earned,” said Susan quietly.

I went on, “But there have been so many deaths…so much slaughter… fearful, dreadful deaths. And the Countess… what had she done?”

“She was a Plantagenet…”

I covered my face with my hands as though to shut out the sight of her. I could see her clearly, walking out of her cell to East Smithfield Green, which is just within the Tower precincts.

“She was very brave, I know,” I said.

“She did not die easily,” Susan told me.

“I would I had been with her.”

“You would never have borne it.”

“And she died with great courage. She… who had done no harm to any. She who had had the misfortune to be born royal.”

“Hush,” said Susan. “People listen at times like this.”

“Times like these, Susan. Terrible … wicked times. Did she mention me?”

“She was thinking of you at the end. You were as a daughter to her.”

“She wanted me to be her daughter in truth…through Reginald.”

“Hush, my lady,” said Susan again, glancing over her shoulder.

I wanted to cry out: I care not. Let them take me. Let them try me for treason. They have come near enough to it before now.

“She did mention you. She asked all those watching to pray for the King and Queen, Prince Edward … and she wanted her god-daughter, the Princess Mary, to be specially commended.”

“So she was thinking of me right to the end.”

“You can be sure of it.”

“How did my dear Countess die?”

Susan was silent.

“Please tell me,” I begged. “I want to hear of it from you. I shall learn of it later.”

“The block was too low, and the executioner was unaccustomed to wielding the axe.”

“Oh … no!”

“Do not grieve. It is over now, but several blows were needed before the final one.”

“Oh, my beloved Countess. She was my second mother, the one who shared my sorrows and my little triumphs during those early years. Always she had been there, comforting me, wise and kind…”

I could not bear the thought of her dear body being slaughtered by a man who did not know how to wield an axe.

All through the years I had not seen her I had promised myself that we should meet one day.

The realization that we never should again on Earth filled me with great sorrow and a dreadful foreboding. How close to death we all were.

MY FATHER WAS in a merry mood those days. He was delighted with his fifth wife. He watched her every movement, and he did not like her to be out of his sight. He took a great delight in her merry chatter. I thought she was rather silly.

When I remembered my father's turning from my mother, from Anne of Cleves, even from Anne Boleyn, I marvelled. All of them were endowed with qualities which this silly little girl completely lacked. Yet it was on her that his doting eyes turned again and again.

Queen of England she might be, but I could not treat her with respect. To me she was just a frivolous girl. It could only have been her youth which appealed to him. He was fifty and she was about seventeen; and he was desperately trying to share in the radiant youth which was hers.