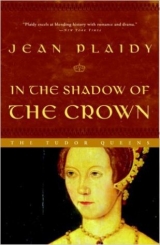

Текст книги "In the Shadow of the Crown "

Автор книги: Jean Plaidy

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 33 страниц)

Table of Contents

COVER

COPYRIGHT

1 – The Betrothal

2 – Reginald Pole

3 – Enter Elizabeth

4 – The Betrayal

5 – The Arrival of Edward

6 – Two Wives

7 – The Queen in Danger

8 – The Planned Escape

9 – At Last–The Queen

10 – Rebellion

11 – The Spanish Marriage

12 – Waiting for the Child

13 – The Queen is Dead–Long Live the Queen

BIBLIOGRAPHY

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

A READER'S GUIDE

ALSO BY JEAN PLAIDY

COPYRIGHT

COPYRIGHT

Copyright © 1988 by Jean Plaidy

All rights reserved.

Published by Three Rivers Press, New York, New York.

Member of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc.

www.crownpublishing.com

THREE RIVERS PRESS is a registered trademark and the Three Rivers Press colophon is a trademark of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Plaidy, Jean. 1906–1993.

In the shadow of the crown / Jean Plaidy. Includes bibliography.

1. Mary I, Queen of England, 1516–1558—Fiction. 2. Great Britain—History—Mary I, 1553–1558—Fiction. I. Title.

PR6015.1314 1989

823'.914—dc19

88-31924

eISBN: 978-0307496140

v3.0

I HAVE TAKEN FOR MY MOTTO “TIME UNVEILS TRUTH,” AND I believe that is often to be the case. Now that I am sick, weary and soon to die, I have looked back over my life which, on the whole, has been a sad and bitter one, though, like most people, I have had some moments of happiness. Perhaps it was my ill fortune to come into the world under the shadow of the crown, and through all my days that shadow remained with me—my right to it; my ability to capture it; my power to hold it.

No child's arrival could have been more eagerly awaited than mine. It was imperative for my mother to give the country an heir. She had already given birth to a stillborn daughter, a son who had survived his christening only to depart a few weeks later, another son who died at birth, and there had been a premature delivery. The King, my father, was beginning to grow impatient, asking himself why God had decided to punish him thus; my mother was silently frantic, fearing that the fault was hers. None could believe that my handsome father, godlike in his physical perfection, could fail where the humblest beggar in the streets could succeed.

I was unaware at the time, of course, but I heard later of all the excitement and apprehension the hope of my coming brought with it.

Then, at four o'clock on the morning of the 18th of February in that year 1516, I was born in the Palace of Greenwich.

After the first disappointment due to my sex being of the wrong gender, there was general rejoicing—less joyous, of course, than if I had been a boy, but still I was alive and appeared to be healthy and, as I believe my father remarked to my poor mother, who had just emerged from the exhaustion of a difficult labor, the child was well formed, and they could have more…a boy next time, then a quiverful.

Bells rang out. The King and Queen could at least have a child who had a chance of living. Perhaps some remembered that other child, the precious boy who had given rise to even greater rejoicing and a few weeks later had died in the midst of the celebrations for his birth. But I was here, a royal child, the daughter of the King and Queen, and until the longed-for boy arrived to displace me, I was heir to the throne.

I enjoyed hearing of my splendid baptism from both Lady Bryan, who was the lady mistress of the Household, and the Countess of Salisbury, who became my state governess. It had taken place on the third day after my birth, for according to custom christenings must take place as soon as possible ble in case the child did not survive. It took place in Greyfriar's Church close to Greenwich Palace, and the silver font had been brought from Christ Church in Canterbury, for all the children of my grandparents, Henry VII and Elizabeth of York, had had this silver font at their baptisms, and it was fitting that it should be the same for me. Carpets had been laid from the Palace to the font, and the Countess of Salisbury had the great honor of carrying me in her arms.

My father had decreed that I should be named after his sister Mary. She had always been a favorite of his, even after her exploits in France the previous year which had infuriated him. It showed the depth of his affection for her that he could have given me her name when she had so recently displeased him by marrying the Duke of Suffolk almost immediately after the death of her husband, Louis XII of France. She was more or less in exile at the time of my christening, in disgrace and rather poor, for she and Suffolk had to pay back to my father the dowry which he had paid to the French. In the years to come I liked to remind myself of that unexpected softness in his nature, and I drew a little comfort from it.

My godfather was Cardinal Wolsey who, under the King, was the most important man in the country at that time. He gave me a gold cup; from my Aunt Mary, the wayward Tudor after whom I was named, I received a pomander. I loved it. It was a golden ball into which was inserted a paste of exquisite perfumes. I used to take it to bed with me and later I wore it at my girdle.

The best time of my life was my early childhood before I had an inkling of the storms which were to beset me. Innocence is a beautiful state when one believes that people are all good and one is prepared to love them all and expect that love to be returned. One is unaware that evil exists, so one does not look for it. But, alas, there comes the awakening.

A royal child has no secret life. He or she is watched constantly, and it is particularly so if that child is important to the state. I say this as no conceit. I was important because I was the only child of the King, and if my parents produced the desired boy, my importance would dwindle away. I should not have been watched over, inspected by ambassadors and received their homage due to the heir to the throne. It is difficult to understand when one is young that the adulation and respect are not for oneself but for the Crown.

There are vague memories in my mind, prompted no doubt by accounts I heard from members of my household; but I see myself at the age of two being taken up by my father, held high while he threw me up and caught me in his strong arms and held me firmly against his jewel-encrusted surcoat. I had felt no qualms that he would drop me. I never knew anyone exude power as my father did. As a child I believed him to be different from all others, a being apart. Of course, I had always seen him as the most powerful person in the kingdom—which undoubtedly he was—and my childish mind endowed him with divine qualities. He was not only a king; he was a god. My mother and Sir Henry Rowte, my priest, chaplain and Clerk of the Closet, might instruct me in my duties to One who was above us all, but in my early days that one was my father.

I was so happy to be held in his arms and to see my beloved mother standing beside me, laughing, happy, beautiful and contented with me.

I remember my father's carrying me to a man in red robes who reverently took my hand and kissed it. My father regarded this man with great affection, and it seemed wonderful to me that he should kiss my hand. It meant something. It pleased my father. I knew by that time that he was my godfather, the great Cardinal Wolsey.

That had been when I was exactly two years old. I think the ceremony must have been in recognition of that fact. It was not only the great Cardinal who kissed my hand. I was taken to the Venetian ambassador and he was presented to me. I had been told I had to extend my hand for him to kiss, which I did in the manner which had been taught me, and I knew this caused my father's mouth to turn up at the corners with approval. Several people were presented to me afterward and I believe I remember something of this. While I was in my father's arms, I saw a man in dark robes among the assembly. I knew him for a priest. Priests, I had been told, were holy men, good men. I was drawn to them all throughout my life. I wanted to see this one more closely, so I called out, “Priest, Priest. Come here, Priest.”

There was astonishment among the company, and my father beckoned to the man to come forward. He did and stood before me. He took my hand and kissed it. I touched his dark robes and said: “Stay here, Priest.” The man smiled at me and, basking in my approval, he overcame his awe of the King and stammered out that the Princess Mary was a child of many gifts and the most bright and intelligent of her age he had ever seen.

People remember that occasion more for the manner in which I summoned the priest than that it was my second birthday and that the King was showing his love for me and that he was becoming reconciled to the fact that he might never have a legitimate son to follow him, which would make me, his daughter, his heir.

I was at that time at Ditton in Buckinghamshire. On the other side of the river was Windsor Castle and there was frequent traffic between the two places. I looked forward to those occasions when the ferryman rowed us across the river. I had my household governed by the Countess of Salisbury, who was a mother to me when my own beloved mother was not able to be with me. She deplored these absences, I knew, and had made me understand that she loved me dearly, and in spite of my reverence for my father, she was the person I loved best in the whole world.

Whenever she visited the household, she and the Countess would talk of me. My mother wanted to know everything I did and said and wore. She made me feel cherished; and the greatest sorrow of my early life was due to those occasions when we had to part.

She would say: “Soon we shall be together again and when I am not here the lady Countess will be your mother in my place.”

“There can only be one mother,” I told her gravely.

“That is so, my child,” she answered. “But you love the Countess as she loves you, and you must do everything she tells you and above all remember that she is there… for me.”

I did understand. I was wise for my years. I had, as Alice Wood, the laundress used to say, “an old head on little shoulders.”

Soon after that, when I was two years and eight months old, my first betrothal took place.

A son had been born to François Premier, the King of France, and my father and the Cardinal believed that it would strengthen the friendship between our two countries if a marriage was arranged for us. Although I was almost exactly two years older—the Dauphin was born on the 28th of February 1518—we were of an age. I had no notion of what this was all about. I do vaguely remember the splendid ceremony at Greenwich Palace, largely because of the clothes I had to wear. They were heavy and prickly; my gown was of cloth of gold, and my black velvet cap so encrusted with jewels that I could scarcely support its weight. My prospective bridegroom, being only eight months old, was naturally spared the ceremony and a somewhat solemn-looking Admiral Bonnivet represented him. I remember the heavy diamond ring he put on my finger.

The great Cardinal celebrated Mass. I was too uncomfortable in my unwieldy garments to be anything but pleased when it was all over.

The Countess told me that it was a very important occasion and it meant that one day I should be Queen of France. I need not be alarmed. The ceremony would not be repeated until the Dauphin was fourteen years old– by which time I should be sixteen… eons away in time. Then I should go to France to be prepared for the great honor of queenship.

My mother did not share in the general rejoicing. I learned at an early age that she did not like the French.

I was three years old when an event took place which was of the greatest importance to my mother and therefore to me, although, of course, at this stage of my life I was blissfully ignorant of it and of the storms which had begun to cast a cloud over my parents' marriage.

Later I heard all about it.

I had sensed that there had been a certain disappointment at my birth because I was not a boy, and I was aware some time before my third birthday that there was an expectancy in the Court which had seeped into my household. People whispered. I caught a word here and there. I think I must have been rather precocious. I suppose any child in my position would have been. I did not know what the undercurrents meant but I did somehow sense that they were there.

My mother was ill and I heard it murmured that this was yet another disappointment, though “it” would only have been a girl. The King was angry; the Queen was desolate. It was yet another case of hope unfulfillled.

“Well, there is time yet,” I heard it said. “And after all there is the little Princess.”

And then a boy was born—not to my mother, though. He was a very important boy, but he could not displace me. He was flawed in some way. He was—I heard the word spoken with pity and a touch of contempt—a bastard.

But there was something special about this bastard.

I learned the story later. Bessie Blount was not the King's first mistress. How my poor mother must have suffered! She, the daughter of proud Isabella and Ferdinand, to be forced to accept such a state of affairs. Men were not faithful… kings in particular… but they should veil their infidelities with discretion. I heard many tales of Bessie Blount; how she was the star of the Court, how she sang more prettily and danced more gracefully than any other; and how the King, tiring of his Spanish Queen who, in any case was more than five years his senior, was like every other man at Court fascinated by her.

There had been another woman before Bessie Blount's arrival on the scene. She was the sister of the Duke of Buckingham and was at Court with her husband. The Duke of Buckingham considered himself more royal than the Tudors. His father was descended from Thomas of Woodstock, who was a son of Edward III, and his mother had been Catherine Woodville, sister to Elizabeth, Queen of Edward IV. So he had good reasons—particularly as the Plantagenets were inclined to regard the Tudors as upstarts. My own dear Countess of Salisbury was very proud of her Plantagenet ancestry but she was wise enough not to talk of it.

However, the erring lady's sister-in-law discovered what was happening and reported it to her husband the Duke, who was incensed that a member of his family should so demean herself as to become any man's mistress, even if that man was the King. Being so conscious of his heritage, he was not the man to stand aside and had gone so far as to upbraid the King. It was really quite a storm and I could imagine the interest it aroused throughout the Court and the anguish it brought to my mother.

The woman was taken to a convent by her brother and kept there. The King and the Duke quarrelled, with the result that Buckingham left the Court for a while. I suppose it was not considered to be a very serious incident but I believe it was the first time my mother had been aware that the King looked elsewhere for his comfort.

The Bessie Blount affair was quite another matter—no hole in the corner affair this. My father was now petulantly showing his discontent. All those years of marriage and only one child—and that a girl—to show for it! Something was wrong and, as my father could never see any fault in himself, he blamed my mother. He convinced himself that he had nobly married his brother's widow; when she was helpless, he had played the gallant knight as he loved to do in his masques and charades, and out of chivalry he had married her. And how had she repaid him? By producing children who did not survive…apart from one daughter. It was unacceptable in his position. He must have heirs because the country needed them. He had been cheated.

There was no longer pleasure to be found in the marriage bed. God had not made him a monk, so it was only natural that he, so bitterly disappointed in his marriage, should turn aside for a little relaxation to enable him to deal effectively with matters of state.

So there was the delectable Bessie, the star of the Court, so enchanting, desired by many. It was natural that she should comfort my father.

Perhaps it would not have been so important if Bessie had not become pregnant; and even that in itself could not have made such a stir. But Bessie produced a boy—a healthy boy! The King's son—but, alas, born on the wrong side of the blanket, as they say.

A ripple of excitement ran through the Court, so obvious that even I, a child of three years, was conscious of it.

When my mother visited me, I noticed a sadness in her. It grieved me momentarily but when she saw this she was determined to hide it and became more merry than she usually was.

I forgot it. But later, of course, looking back, I saw that it was, in a way, the beginning.

The boy was named Henry after his father. He was a bright and goodlooking child, and the King was proud of him. He was known as Henry Fitzroy so that none should forget whose son he was. Bessie was married to Sir Gilbert Talboys, a man of great wealth, for it was considered fitting that as she was a mother she should be a wife. The boy must have the best and his father saw much of him. My mother used to talk to me about it during those dark days when the King's Secret Matter was, in spite of this appellation, the most discussed subject at Court.

When I was four years old, my parents went to France. There was a great deal of excitement about this visit because it was meant to mark a new bond of friendship between France and England. The King of France and my father were going to show the world that they were allies; but mainly they were telling this to the Emperor Charles, who was the rival of them both.

I wondered whether they would take me with them. But they did not. Instead I was sent to Richmond. This was a change from Ditton, although I had my household with me and the Countess and Lady Bryan were in charge. But the Countess did try to impress on me that it was different because my parents were out of the country and that put me into a more important position than I should have been in if they were here. I tried to grasp what this meant but the Countess seemed to decide that she could not explain. I heard her say to Lady Bryan, “How can this be expected of a child?”

There was a great deal of talk about what was happening in France and there were descriptions of splendid tournaments and entertainments. The occasion was referred to as “The Field of the Cloth of Gold,” which conjured up visions of great grandeur in my mind. My mother told me later that it was not all they had thought it was while it was in progress.

I have always deplored the fact that I missed great events and that they came to me by hearsay. I often told myself that, if I had been present, if I could have experienced these important occasions when they happened, I could have learned much and been able to deal more skillfully with my own problems when they arose.

It was while my parents were in France that three high-ranking Frenchmen came to the Court.

This threw the Countess into an agony of doubt. I heard her discussing the matter with Sir Henry Rowte.

“Of course, we have to consider her position. But such a child…Oh, no, it would be impossible, and yet…”

Sir Henry said, “Her extreme youth must be considered by everyone. Surely…”

“But who is to receive them? She is… who she is…”

I understood that they were talking about me.

A decision was arrived at. The Countess came to my schoolroom where I was having a lesson on the virginals.

“Princess,” she said, “important gentlemen have come from France. If the King or Queen were here, they would receive them, but as you know, they are in France. So … as their daughter … you must greet these arrivals.”

It did not occur to me that this would be difficult, and I suppose, as I felt no fear, I carried off the meeting in a manner which, on account of my youth, surprised all who beheld it. I knew how to hold out my hand to be kissed. I knew that I must smile and listen to what was said and, if I did not understand, merely go on smiling. It was easy.

I was aware of their admiration, and the Countess looked on, pursing her lips and nodding her head a little as she did when she was pleased.

One of the gentlemen asked me what I liked doing most. I considered a while and then said that I liked playing on the virginals.

Would I play for him? he asked.

I said I would.

I heard afterward that everyone marvelled at my skill in being able to play a tune without a fault. They said they had never known one so young such a good musician.

The Countess was gratified. She said my parents would be delighted to hear how I had entertained their guests during their absence.

Often during the years that followed, I would look back on those early days and fervently wish that I had never had to grow up.

In due course my parents returned from France. There was still a great deal of talk about the brilliant meeting of the two kings. I kept my ears open and heard scraps of conversation among the courtiers when I was with the Court. I learned how the two kings had vied with each other, how they were determined to show the world—and the Emperor Charles—that they were the best of friends. When they were in church together, each king had stood aside for the other to kiss the Bible first, and at length the King of France had prevailed on the King of England to do so, as he was a guest on French soil. My mother and the Queen of France had been equally careful of each other's feelings. I knew my mother had great sympathy with Queen Claude. I heard the whispers: François was a libertine with whom no woman was safe, and poor crippled Claude had a great deal to endure.

That occasion when the King of France had forced his way into my father's bedroom when he was in bed was much discussed. My father had said, “I am your prisoner,” but the King of France had charmingly replied, “Nay, I am your valet.” And he had handed him his shirt. It was all elaborate play-acting to show the amity there was between them and to warn the Emperor Charles—who was a most ambitious young man—that he would have to face the might of the two countries, so he had better not think about attacking one of them.

On that occasion my father gave François a valuable jeweled collar, and François responded by giving him a bracelet of even greater value. That was how it was at the Field of the Cloth of Gold. Each king had to outdo the other; and because of the shift in interests, because of the wily and unpredictable games they played, very soon it became clear to both participants that the entire venture had been an enormous waste of time and riches.

When my mother returned from France, young as I was, I detected that she was not happy. I understood later that she did not like the French; she did not trust François—and how right she was proved to be in that. Moreover, she had been most uneasy because the entire farce of the Field of the Cloth of Gold had been an act of defiance against the Emperor Charles. My mother was Spanish and, although she was devoted to my father, she could not forget her native land. She had loved her mother as passionately as I was to love her and she me. It could not give her any pleasure, considering her strong family feeling, to witness her husband joining up with an ally in order to stand against her own nephew.

At this time there were three men of power astride Europe; they were François Premier of France, Charles, Emperor, the ruler of Spain, Austria and the Netherlands, and my father, the King of England. They were all more or less the same age—young, ambitious, determined to outdo each other. There was a similarity between François and my father; Charles was different. Not for him the extravagances, the lavish banquets, the splendid tournaments, the glittering garments. He was quiet and serious.

My mother was torn between husband and nephew. It grieved her greatly to think of them as enemies. She could not, of course, explain this to me at that time.

When my parents returned from France, after a short stay with them I went back to Ditton Park; but the following Christmas I was with them. Although I dearly loved the Countess of Salisbury, Lady Bryan and all my household, I looked forward with great pleasure to being with my parents. My father was such a glittering figure, and it delighted me, even at that early age, to see how he inspired a certain awe in everyone near him; even the greatest men, like the Cardinal, whom all respected and feared, bowed to my father. He had a loud laugh and when he was merry his face would light up with joy and everyone around him would be happy. I had seen him, though rarely, in a less than merry mood. Then his eyes would be like two little points of blue ice and his mouth would be such a small thin line that I thought it would disappear altogether. A terrible fear would descend on the company, and it appeared to me that everyone would try to shrink out of sight. It was awesome and terrible. Someone usually hurried me out of the way at such times.

So, while I worshipped him, I did experience a little fear even in those days. But that only made him the more godlike.

With my mother I felt safe and happy always. She was dignified and aloof, as became a queen, but always warm and loving toward me and while I was proud to have such a glittering, all-powerful father, I was more deeply contented in the love of my mother.

That Christmas I spent with them was one I remember well. There were so many presents—not only from my parents but from the ladies and gentlemen of the Court. I remember the gold cup because it came from the Cardinal, and the silver flagons I think were from Princess Katharine Plantagenet, who was quite old, being the daughter of my great-grandfather, King Edward IV. In contrast to these valuable presents was one from a poor woman of Greenwich. She had made a little rosemary bush for me all hung with gilt spangles. It gave me as much pleasure as any.

My mother made it a Christmas to delight me and sent for a company of children to act plays for me. I remember some of those plays well. They were written by a man called John Heywood who was later to make quite a success with his dramatic works.

Those early years were spent mainly in the calm serenity of Ditton, with occasional visits to my parents. These memories are of laughter, music and dancing, of cooks and scullions rushing hither and thither with great dishes of beef, mutton, capons, boars' heads and suckling pigs, and in fact any meat it was possible to think of; of eating, drinking and general merrymaking, with my father always at the center. He could sing and hold the company spellbound—perhaps as much by his royalty as his talent; but there was no doubt that in the dance he could leap higher than any; he was indefatigable. No stranger, seeing him for the first time, could have doubted that he was the King and master of us all.

I was proud to be his daughter, and if I could have had one wish it would have been that my sex might be changed, so that I could be the boy who would have delighted him as Henry Fitzroy did and so rid my mother of that look of anxiety which I saw more and more frequently in her face.

But perhaps Henry Fitzroy felt something of the same, for he could not give my father complete pleasure because he was illegitimate. So he was flawed even as I was.

Shortly after my parents returned from France, something happened which caused anxiety to my godmother, the Countess of Salisbury. At my tender age I was aware only of a ripple of disturbance, and it was not until later that I understood what it meant.

It concerned Edward Stafford, Duke of Buckingham, whose rank brought him close to the King, and on the surface they were good friends. Just before the party went to France, Buckingham had entertained the King lavishly at Penshurst. I heard people talking about the masques and banquets which had been of such splendor as to surpass even those given by the King himself.

Buckingham was not a wise man. He could never forget his royal descent and would remind people of it in any way which offered itself. He should have remembered that, although he was so proud of it, in the mind of a Tudor it could arouse certain suspicions. A clever man would have been more subtle, but from what I heard of Buckingham he had never been that. The King might enjoy the entertainments while they lasted, but afterward might he not ask himself: Why should this man seek to outdo royalty? The answer was, because he regarded himself as equally royal… no, not equally, more so.

It was true that the Tudors' grip on the crown was not as secure as they would wish. My grandfather, Henry VII, had seized it when he defeated Richard III at Bosworth Field in 1485; and many would have said that his claim to it was not a very strong one. Buckingham was one of those. Later I was to see my father's eyes narrow as he contemplated such men. At that time he was more tolerant than he became later. Then he delighted in the approval of his subjects, but later he only wished them to accept his rule. It was up to them to like it or risk his displeasure. My father was a man who changed a great deal over the years. At this time he was only just passing out of that phase in which he appeared to be full of bonhomie and good will toward men, which made him the most popular monarch men remembered. It was the growing discord in his marriage which was changing him; he was turning from a satisfied man to a disgruntled one, and that affected his nature and consequently his attitude toward his subjects.

Buckingham had powerful connections in the present as well as the past. He was married to a daughter of the Percys, the great lords of the North. His son—his only one—had married the Countess of Salisbury's daughter, so that made a family connection between him and my godmother. Small wonder that she was worried. He had three daughters, one of whom had married into the Norfolk family, one to the Earl of Westmorland and the third to Lord Abergavenny. So it was clear that Buckingham was well connected.