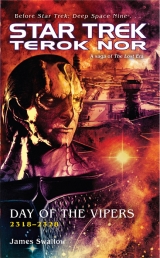

Текст книги "Days of the Vipers"

Автор книги: James Swallow

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 2 (всего у книги 30 страниц)

“And what about Cardassia’s good?”

Ico sighed inwardly. The priest did not know when to be silent. Ignoring Hadlo’s hand on his arm, he turned to face Kell, his cheeks darkening with anger. A more seasoned man might have known that this conversation was on a downward spiral, but Bennek was not a seasoned man. Ico knew that there was only one way this meal would end now, and it would not be quietly.

“Instead of sending ships to blockade Talaria, why not use the taxes paid to build them to construct hospitals and fabricators instead?” Bennek continued. “Then there would be no hungry millions, Gul Kell. If there were no great Cardassian war machine, there would be no need for the poor to starve! There would be no need for this mission, for us to seek aid from worlds like Bajor!”

“We do not seek aid from Bajor,” Hadlo broke in, “only a partnership in kind that will—”

Kell glared over his glass at the young man, ignoring the old cleric’s words. “Oh yes, there would be such peace and riches if only the Central Command did not squander our Union’s scarcity of wealth on warships,” he said in an arch voice. “How many times have I heard that from the lips of fools who have never left the homeworld, fools with their noses buried in scrolls full of dusty old legends!” He put down his drink hard and aimed a finger at the priest. “Oh, there would be such peace, Bennek, such peace indeed, and food aplenty for even the lowest commoner to gorge upon! Perhaps your utopia might last a week, a month at the most, before our worlds were crushed under the boot heels of invaders! Tholians, Breen, Tzenkethi, whichever ones got there first…And the people would ask you ‘Where are our defenders, Bennek? Where are our swords and shields?’ And you would have to tell them that you traded their safety for a few full stomachs!” He drew himself up, his dark duty armor glinting dully in the dining chamber’s muted orange lights. “You are right about one thing, boy. Cardassia islean and hungry, and it must remain that way. A fat, content animal is a slow one, a victim in waiting. A hungry animal is a predator, feared by the herd.”

Ico kept her face neutral, but beneath her placid expression she wanted to laugh at the man’s retort. Kell’s armor did only a passing job of hiding a well-fed girth that showed the gul’s leanings toward indulgence and excess.

“You mistakenly believe that your participation in this mission allows you a degree of leeway, of input.” Kell glared at Bennek and his master. “It does not. You Oralians, with your chanting and your ridiculous masks, you think your rituals have great majesty and import, but they are meaningless to me. You are aboard the Kornaireon my sufferance, because I have been ordered to take you to Bajor.”

Hadlo gaped. It was clear to Ico that the cleric had never expected Kell to speak so bluntly in front of his aide. “This delegation…” Hadlo said, struggling to recover some dignity. “The Detapa Council asked the Oralian Way to initiate this diplomatic mission! We are leading it!”

“As a way of building bridges between our two peoples,” the gul said dismissively. “Yes, yes, I recall the words of the First Speaker. And as far as the Bajorans will know, that is the truth. But the reality—the Cardassian reality—is much different. This operation is wholly under the guidance of Central Command, not your Way, not the Detapa Council. The military alone will decide how events will play out,” he sniffed, leaning toward Bennek. “So remember that, boy. And remember your place.”

With brittle grace, Hadlo used a napkin to wipe the corners of his lips and stood up, his meal completely untouched. Bennek followed suit, the young man wired with pent-up anger. “If it pleases the gul, we will take our leave of you,” said the cleric tightly. “We must prepare for the evening’s recitations.”

Kell waved them away, his attention turning to the table to find a succulent seafruit.

Ico stared at the door after it closed on the priests’ backs. She found herself wondering if Kell realized that he was as much wrong as he was right about who was really directing the mission to Bajor.

Pa’Dar blinked and ate some more of his broth, unsure of how to proceed. Finally, he changed the subject. “Any news from home? The communications feeds we receive on the lab decks are quite sparse.”

“Censorship is commonplace in the military,” Dukat replied. “You learn to read through it after a while.” He toyed with the bread. “I know the question you really want to ask me, Kotan.” He nodded. “This mission remains classified for the moment.”

“Oh, no,” said the scientist, lying poorly. “I was not concerned for myself. I was just wondering…what with the news of the famine in the southern territories just before we left home orbit. Have things improved at all?” He managed a weak smile. “Your family are there, isn’t that so?”

Dukat’s lips thinned, and without really being aware of it, the officer’s hand strayed to the cuff of one of his sleeves. There was a small pocket there, and inside it a holograph rod. He didn’t need to look at it to remember the images encoded there: a woman, his wife Athra, her amber eyes a mix of joy and concern; and the child, his son, swaddled in the birthing blanket that Skrain himself had once been carried in. He thought of the sallow cast to the baby’s cheeks beneath the fine definition of the Dukat lineage’s brow, and a sharp knife of worry lanced through him. It showed in the flicker of a nerve at his eye, and the dalin knew immediately that Pa’Dar had seen it.

In front of any other crewman, if he had been in the company of Gul Kell or any of the others, he would have hated himself for revealing such a moment of weakness, but Pa’Dar simply nodded, understanding. “Family is all that we are,” intoned the scientist, the ancient Cardassian adage coming easily to his lips.

“Never a truer word spoken,” agreed Dukat. “The famine continues,” he went on. “The First Speaker has authorized the transfer of supplies from the stockpiles in Tellel Basin and Lakarian City. It is hoped that will lessen the problem. I admit I am not as convinced of that as the Council appears to be.”

Pa’Dar seemed to sense the dark turn the conversation was taking and covered with a sip of water. “My family believe I am assisting the Central Command in a mapping exercise near the Amleth Nebula.”

“As good a cover as any.”

The scientist eyed him. “Amleth is perfectly well mapped as it is, Skrain. Such an assignment is an obvious fake, and if my family know that, they may believe the worst—that I am in harm’s way, sent into Talarian space or off toward the Breen Arm on some secret errand.” He blew out a breath. “I don’t want them to be afraid.”

“Then you should be glad. Bajor is hardly a conflict zone. I doubt we’ll face anything more threatening there than the weather. I understand it’s rather intemperate.”

“For Cardassians,” noted Pa’Dar. “Although apparently the coastal regions along the equator do have a temperature range we would consider more favorable.” He nodded toward one of the many padds on the table before them, and Dukat noted the image of a green-white world turning slowly in a time-lapse simulation. “Your family is from Lakat, yes? In the colder climes?” asked the scientist. “You’ll probably find Bajor not too dissimilar to your home in the depths of the winter months. Our reports on their climate show it’s less arid than Cardassia, likely with an extended growing season. It certainly appears more verdant.”

“Indeed.” Dukat studied the alien planet. It reminded him of a ripe fruit on the vine, heavy with seeds and juice. Absently, he licked his lips and looked away, returning to his earlier point. “Think how pleased your family will be when you return to Cardassia after this mission is complete,” the dalin told the other man. “You’ll be well, unhurt, and more worldly from your travels, and with luck on our side we will come home with the glory of a new ally for the Cardassian Union.”

“An ally,” repeated Pa’Dar. “‘Cardassia always leads, never walks in step.’ Isn’t that how the maxim goes? Do the Bajorans know that? Do they even know we are coming?” Doubt clouded the young man’s face.

Dukat sensed the faint reproach in the civilian’s words, and for the first time he wondered if he might have been in error befriending the scientist. Perhaps he had been too open, perhaps he should have maintained the aloofness of his fellow officers; but it was too late now to concern himself with such thoughts. “The Bajorans know us,” he began carefully. “We’ve crossed paths with their people on occasion, on their outer worlds, in the reaches of unclaimed space. This will be a formal first contact, Kotan. An event of great import for both races. And I’m sure the Bajorans will immediately understand the enormous benefits that Cardassia’s friendship can bring.” The mere thought that any other outcome was possible seemed so unlikely to Dukat as to be hardly worth considering. He dismissed the dour look of doubt on Pa’Dar’s face. “You’ll see, Kotan. It will be a great opportunity for all of us. How often does someone of your status get the chance to take part in a delegation of this kind?”

“Yes,” admitted the other man. “You are correct on that point. I admit, I am quite intrigued by the prospect of learning more about these aliens.”

Dukat nodded again. “Just so.” He felt a tension in his fingers and covered it by taking another spoonful of the broth. He did not doubt that Pa’Dar was a far more intelligent man than he, but for all his academic knowledge Pa’Dar lacked an understanding of the realities of things. Bajor would become an ally of the Cardassian Union, simply because Cardassia required it. The path that would bring them to that destination was unclear to the dalin for the moment, but he had no doubt that it would open to him as time went by. Dukat felt a certainty of purpose about the mission, a determination that coiled hard and cold in his chest; he thought of his wife and his child at home, of their modest accommodation in the extended family quarters of his father’s house in Lakat, and that determination became firmer still. It was for them that they were doing this, it was for them that he would see the Kornaire’s mission a success.

Ico poured another glass of rokassafor herself and then one more for Kell. “Was that really necessary? You gain nothing by alienating the ecclesiasts.”

The gul made a face. “Incorrect, my dear Rhan. I gain some entertainment for myself on this most ordinary of voyages. If I have no pirates or border violations to take my frustrations out on, then these Oralians will do just as well. I’m only sorry I’m not allowed to space the whole band of insufferable prigs.”

She sighed. “At least promise me you will not antagonize Hadlo’s aide any further. When we reach Bajor, it would not do for the first sight the aliens have to be Bennek’s hands about your throat.”

“Let him try. Soft little priest with his soft little hands. I’d soon teach him that blind zealotry is no substitute for focus of will.” Kell took a gulp of the fluid.

“Like it or not, we need them. We need that zeal.”

He nodded with a grimace. “Yes, I suppose so. And so I will tolerate them, for Cardassia.” He saluted the name with his glass. “At least until this is over. Once they’ve served their purpose, the Union can go on about the business of erasing them from our society.”

Ico paused as she ate and cocked her head. “You really do detest the Oralians, don’t you, Danig?”

He stared into his drink, musing. “They’re the worst of us. The very last vestiges of the old race we were before Cardassians came to understand their place in the universe. Throwbacks, Rhan, nothing but anachronisms.” Kell’s lip curled. “That arrogant young whelp, he’s a perfect example. He has the nerve to accuse the military of impoverishing our nation, we who defend it!” The gul tapped a balled fist on his chest plate, touching the copper sigil of the Second Order affixed there. “But it’s his religion that is to blame! They’re the ones responsible for the state of Cardassia, not us!” He turned in his seat, his ire building again, and fixed her with a look. “How many centuries were our people forced to live under the yoke of the Oralian Way? With every measure of wealth, every stone and scrap of jevonite going to build towers of worship? Places where the people could huddle and listen to hollow promises of salvation and redemption, when there was nothing!” Kell waggled a finger at Ico. “They repressed us, kept Cardassia from advancing. If Hadlo and his kind had their way, we would still be living in crude huts, our learning stunted by their dogma. You, Rhan, what would you be? Not a scientist! Some temple servant, perhaps, or a doting wife walking ten paces behind your husband!”

Ico said nothing. The years when the church had been the governing force behind Cardassian society were long gone, but there were many who still carried a strong resentment toward the customs of the old credo. It mattered nothing to Kell that Hadlo’s faith was now only a pale shadow of the religion that had once dominated Cardassia’s pre-spaceflight era. The gul’s ignorance of the tenets of the Oralian Way was obvious by his words, but she knew that correcting him would gain her nothing. She simply nodded and let him continue.

“The future for Cardassia lies out here,” he growled, jerking a thumb at the oval viewport high on the wall, at the stars outside turned to streaks of color by the ship’s warp velocities. “Not in some ancient doctrine.” He grimaced again. “Were I First Speaker, I’d have fed the lot of them to the Tzenkethi by now. They held us down, they wasted our resources. If not for the military, we would still be a downtrodden and backward people. Now every day we have to struggle to claw back the time those foolish priests cost us.”

“And yet here they are, with us on this most sensitive of assignments. Do you find the irony in that as I do, Kell?”

The gul eyed her. “The Detapa Council believes those ridge-faced primitives on Bajor will be better disposed toward a Cardassia that exhibits some of the same childish fealty to religion that they do. Hadlo and his band of fools are only here to maintain that fiction. To mollify the aliens, nothing more.”

She nodded. “From a certain point of view, such a tactic might be seen as a desperate one.”

“What do you mean?”

Ico took another sip. “Has the Central Command grown so unsure of itself that it must enlist priests to help it gain a foothold on Bajor? Are our proud warfleets spread so thin that we cannot simply take Bajor by force of arms?” She gestured around. “One ship, Danig. Is that all the Orders can spare from the wall of vessels protecting our space?” She knew the answer to those questions as well as Kell did, but neither of them would dare to say it aloud. Not here. Not yet.

His eyes narrowed. “I would advise you to watch your tone, Professor.”

“Forgive me, Gul Kell,” she replied. “In my line of work, it is the nature of a scientist to make suppositions and voice theories.”

Kell looked away without even bothering to grace her with a response.

2

B’hava’el was low in the sky across the rooftops of the dockyards and the port hangars, throwing warm orange light through the clouds, but the chill of last night’s storm down from the mountains was still hugging the ground. For most people in Korto, the day hadn’t really begun. Trams on the main thoroughfare were filled with workers coming in from the habitat districts, the rail-riders passing equally full carriages going the other way packed with night servants, cleaners, and members of professions that shunned the light of morning. Darrah Mace walked the edge of the city’s port field, occasionally glancing to his right to watch the highway traffic on the other side of the chain-link fence, but for the most part keeping his gaze northward, across the hangars and landing pads, over the grassy spaces around the runways. Ships clicked and ticked to themselves as he passed around them, some vessels dripping with runoff from the rain, others bleeding warmth from atmospheric reentry. He raised a hand and threw a wan salute at a group of laborers clustered around the impulse nacelle of a parked courier; they were using a crude steel plate to fry eggs on the ship’s heat exchangers. One of them offered him a greasy slice, but Darrah shook his head good-naturedly and walked on. The scent of the makeshift cooking lingered in the air, following him on gusts of wind that made his overcoat twist and flap.

He’d heard there had been some trouble here last night, something about a fight interrupted, threats, and an issue or two unresolved. It was hardly atypical for the port. Darrah experienced a moment of memory from his childhood, triggered by the cook-smell: walking along after his father to go see the big lifter ships where the old man had worked, the loaders and dockers all laughing against the grim exertion of their chores. Then an argument had broken out, and one man had beaten another with a bill-hook. His mother had been furious that the boy had been allowed to see that. She’d never let Mace follow his dad to work again. She’d never understood that the blood, the violence, hadn’t frightened him. Mace had been with his father, who protected him. He thought about his own children for a moment, about hisjob; a bitter smirk formed on his lips as he imagined what Karys would say if Nell or little Bajin asked to follow himto work. “She’d pitch a fit,” he said aloud.

Darrah hesitated at the edge of the landing apron, his chilly amusement turning swiftly into a frown. There was nothing here, and he’d done his part by just turning up, just taking a stroll around the port so people knew he was there. The laborers had seen him. They’d spread the word that Darrah had been around. That was probably enough. He pivoted on his heel, hesitating just for a moment as engine noise caught his ears. He stopped to watch as a slim, wire-framed freighter rose up on vertical thrusters from one of the elevated pads, turning a snake-head prow toward the sky. With a sharp report of ion ignition, gouts of smoky exhaust puffed from the ship’s engine bells and it shot away like a loosed arrow, roaring right over his head toward the south and the ocean. He watched it go, receding to a dot, for a moment being the young boy again; and then he realized that the noise of the liftoff had been hiding something else. Angry voices, from close by.

Darrah went quickly through the maze of alleyways between the day-rental hangars and forced himself to slow to a casual walk as he rounded the corner, bringing the site of the dispute into view. He took in the crescent-shaped ship sitting half in and half out of the hangar, and faltered. He recognized the craft instantly, and for a moment he considered just turning and walking away, leaving the situation to play out as the Prophets intended. But only for a moment. The vessel was an odd bird, the fuselage of a decommissioned Militia impulse raider married to a brace of refurbished warp drives off an Orion schooner. It had a mutant, misshapen air to it, as if the craft were the result of some unfortunate mechanical crossbreeding experiment. It didn’t look like it should be flying, but Darrah knew full well that the pilot encouraged that appearance in a vain attempt to make it draw less attention. And the pilot in question, well, he was being pressed into the side of his ship by a man who had twice his mass, wearing dark clothes and a gaudy Mi’tinoearring. Darrah frowned. In his experience, clans from the Mi’tinocaste always had a sense of entitlement about them that made for poor relationships with anyone they considered a “lesser.” Like, for example, a skinny shuttle jockey in an ill-fitting tunic.

Darrah cleared his throat, and the Mi’tinoman paused with his fist cocked to punch his victim squarely in the gut. The pilot caught sight of Darrah for the first time, and his face flushed with relief, some color returning to his nasal ridges. “Ha!” The pilot managed. “You’re gonna regret this now! Do you know who that is? He’s only—”

“Syjin, shut up,” snapped Darrah. “What are you doing?”

“What am Idoing?” Syjin retorted, coughing because the big guy had him by the throat. “What are youdoing, standing there and watching this lugfish manhandle me?”

Darrah stroked the stubble on his chin thoughtfully. “I’m sure it isn’t anything you don’t deserve. Let me take a wild stab in the dark here and say that you’re the person who was in danger of getting his head caved in here last night?”

“Yes,” said the pilot. “Possibly. It’s a big port.”

“Hey,” began the man in the dark jacket, angry at the new arrival. “Get lost!”

“Not that big.” Darrah kept talking, ignoring Syjin’s assailant. “I bet you deserve it. Can’t you keep out of trouble for one single day? I mean, would that be too much to ask?” He was advancing as he spoke, letting his coat fall open a little. “Remember old Prylar Yilb at temple school? He was right about you. You’re on a road straight to the Fire Caves, my friend. Damnation eternal.”

“Hey,” repeated the Mi’tino,but they weren’t listening to him.

Syjin’s eyes widened. “Yeah, right after you, Darrah Mace! I’m not the one who broke the icons in the vestry! I’m not the one he made write out all of Gaudaal’s Lament a hundred times!”

Darrah threw up his hands. “Oh, this again?I was nine years old! Are you going to keep bringing up that story forever?”

Finally, the act of being ignored by the two men was too much for Syjin’s attacker, and he turned on Darrah, still holding the pilot in place. “Hey!” he shouted. “I told you to get lost! Who the kosstdo you think you are?”

Without moving too fast, Darrah pushed back his coat to reveal the earth-toned uniform he was wearing underneath it, the duty fatigues of a law enforcement officer in the Bajoran Militia. “I’m the police, friend. And that man, sadly, is a Korto citizen, and so I have to reluctantly consider him under my protection.” He nodded at Syjin. “Why don’t you stop choking him there and we’ll try to settle this with some decorum?”

The man in the dark jacket swore a particularly choice curse that suggested Darrah’s mother should take congress with farm animals, and what little of Darrah’s good mood remained instantly evaporated. He lunged, quick enough to take the man off guard, and caught him in a viselike grip, his hand pulling hard on the assailant’s right ear. Darrah twisted and pulled at the earring denoting the Bajoran’s D’jarracaste, putting savage pressure on the lobe. The man howled and stumbled away, releasing Syjin and flailing.

“Something else Prylar Yilb used to say was, you could tell a lot about a man from the way his paghflowed,” Darrah growled. “Let’s see what we can learn about you, huh?” He gave the ear a hard yank, and the man overbalanced and fell into a heap on the thermoconcrete landing pad. Darrah let him go and shot Syjin a look. “Hm. Not much. The ear of any good Bajoran is supposed to be the seat of their Prophet-given life force, but our friend here doesn’t seem to have anything there but wax.” He made a face and wiped his hand on his coat.

“Bloody Mi’tino!”wheezed the pilot. “You think you can push me around because your D’jarra’s higher up the wheel than mine?” Syjin rocked back and forth on his heels, emboldened by Darrah’s presence. “I might just be Va’telo,but I still deserve respect!” He nodded to himself and attempted to straighten his clothing.

“This isn’t about that!” snarled the man, getting to his feet with one hand pressed to his pain-reddened ear. “This is about you sleeping with my wife!”

“I didn’t sleep with her!” Syjin blurted. “It’s your brother who’s doing that! I just flew her out to meet him on Jeraddo!”

The redness unfolded across the man’s entire face as anger overwhelmed his reason. “You little maggot! I’ll kill you!” Out of nowhere a glitter of silver slid from a pocket in the sleeve of the man’s jacket, and suddenly he was holding a shimmerknife.

Darrah felt a familiar, icy calm wash over him, and by reflex his hand dropped to the holster on his belt. “Don’t do this,” he said.

“I’ll kill you both!” roared the husband, blind fury propelling him forward. The knife came up in a line of bright metal; then the phaser pistol was in Darrah’s hand and the short, sharp keening of an energy bolt crossed the distance between them. The man hit the deck for a second time, the small vibrating blade skittering away from his nerveless grip.

With a heavy sigh, Darrah reached inside his coat and tapped the oval communicator brooch on the right breast of his uniform tunic. “Precinct, this is Darrah. I need a catch wagon down at the port, hangar nineteen. Got a sleeper here, aggravated assault.”

“Confirmed, Senior Constable Darrah,”said the voice of the synthetic dispatcher. “Unit responding. Remain on-site. Precinct out.”

“Wah,” said Syjin, “you shot him. Thanks, brother. He would have murdered us both.”

“Don’t ‘brother’ me, you crafty son of a Ferengi. You’re not family, you’re my bloody penance.”

Syjin pulled a hurt face and leaned down to examine the unconscious man. “Oh. Charming. Old Yilb used to say that all men are brothers in the Celestial Temple.” He reached for a pocket on the other man’s jacket, and Mace smacked his hand.

“Yeah, well, if you ever find it, you can start calling me brother then, not before.” He blew out a breath, studying the man. “Poor idiot. His wife cuckolded him, no wonder he was furious.”

“That’s why I steer clear of the ladies,” Syjin said sagely. “Never let myself get tied down.” He patted his ship. “This is the only mistress for me.”

“Right,” Darrah said dourly, “but you’re more than happy to take a woman’s money to fly her away for some offworld adultery. I’m sure if I looked hard enough I could find a law against that.”

Syjin’s smile froze. “Ha,” he managed. “Oh, before I forget. I’ve got something for you and the children.”

“Don’t try and change the subject!” Darrah snapped, but the pilot was already inside his ship.

A moment later he returned with a hard-sided cargo container. “Here. This is for you and Karys and the little ones.”

Darrah opened the box and inside he saw a few seal-packs of exotic alien foodstuffs. Agnamloaf and methrineggs, a bottle of tranyaand some hydronic mushies, the kind that Nell loved. “Where’d you get this? Is this a bribe?”

“No!” Syjin said hotly. “Can’t a man give his old friend a gift? You’re so suspicious!”

“Suspicion is what makes me a policeman. And, let’s be honest, you have always had a rather elastic relationship with the law.”

The pilot folded his arms. “It is the Gratitude Festival this week, isn’t it? I thought I’d give you a small something to be grateful for. The Prophets smile on men who share their good fortune, right?”

Darrah felt slightly chagrined by his initial reaction. “Oh. Thank you.” He looked up as a police flyer drifted in over the tops of the hangars and angled to land nearby. “As you’re on-planet, are you going to come to the house? The kids would love to see you.”

“I shouldn’t,” said Syjin. “You know Karys thinks I’m a bad influence on them.” His expression turned more serious. “Besides, I think the little ones would rather spend the holiday with their mother and father than silly Uncle Syjin.”

A frown crossed Darrah’s face. “Festivals don’t police themselves,” he said defensively. “I have to keep on top of it. Besides, a wife, a home, and two growing cubs…Constable’s pay can only go so far. I need the extra duties.” He nodded as Proka, one of the duty watchmen, climbed out of the flyer.

“There are other ways to earn latinum,” said the pilot airily as Darrah walked away.

“That’s true,” Darrah said over his shoulder, “and if I catch you doing one of them, I’ll put you in the blocks and grind up that tub of rust for spares.”

“Thank you very little,” Syjin snorted, and went back into his vessel.

The Kornaire’s hangar bay was one of the few areas on board the starship where the ceiling didn’t hang low over the crew’s heads. It was a peculiarity of this variety of vessel; unlike the newer Galor-class ships, the Selek-class heavy cruiser appeared to have been designed by a man of shorter stature. Dukat had heard the enlisted men making jokes when they thought he couldn’t hear them, that Gul Kell kept his flag on the Kornairenot because he’d commanded the ship for so many years, but because striding the vessel’s corridors made him feel taller. Dukat felt fairly indifferent about the ship himself; Kell’s vessel had too many memories attached to it for the dalin, too many recollections of incidents and tours of duty that didn’t sit well with him. Not for the first time, Dukat considered what kind of vessel he would take when his promotion to gul finally came. Something more impressive than this old hulk,he told himself.

Crossing behind one of the Kornaire’s space-to-surface cutters, he found Kotan Pa’Dar waving a tricorder over the drum-shaped shuttle on the tertiary pad. The tan-colored ship was a sorry sight, most of the forward quarter a mess of compacted metal and broken fuselage. The drop-ramp hatch at the rear was open, and inside Dukat could see the bodies wrapped in thick white cloths, piled against the bulkhead like stacked firewood.

Pa’Dar nodded to him. “Skrain,” he said, by way of greeting. “Do you require something of me?”

Dukat shook his head. “Just making my rounds,” he explained. The dalin gestured at the wreck. “All is well?”

The scientist peered at the tricorder’s readout. “We made sure the drive cores were pulled before the craft was brought on board. There’s no residual radiation or isolytic leakage, but it never hurts to check.” He shrugged. “It is alien technology, after all. We can’t be certain we’ve accounted for everything.”

The officer walked to the hull of the ship and placed a hand on it. “Bajorans breathe the same sort of air as us. They have the same sort of gravity, eat compatible foodstuffs…It’s no surprise their ships are not that different from ours.” His fingers found a fitting on the fuselage, a bolt and pinion connection that had been sheared off. Dukat frowned, unable to identify it.