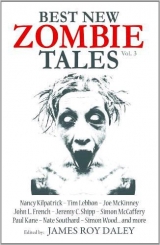

Текст книги "Best new zombie tales, vol. 3"

Автор книги: James Daley

Жанр:

Ужасы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 8 (всего у книги 20 страниц)

"You say that now. Let's see if you ask me again in five minutes."

"Maybe I'm not your normal clientele."

He sighs. "No, we don't feel much pain, so clear your fucking conscience."

"Are you just telling me that or do you mean it?"

He runs his hand down his face. "Look, man. You can either do this or go home. But no one ever goes home, so just face the fucking music and get on with it."

So I do. I start off by slapping him hard across the face, and go from there. Five minutes later, I'm not asking, "Is this hurting you?"

Five minutes later, I'm straddling his chest, smashing his mangled face in with my bloody fists, over and over and over. He's shouting, "Stop it!" and I'm loving every second of it.

Hafwen's nickname is Zippy. She likes to skip and sing about the dishes as she's washing them, and write poetry with waterproof paper in the rain. She'll call me up just to tell me that she's discovered the name for those imprints left in the skin when you press it against a textured surface too long. A frittle.

So when I see her sitting cross-legged on my bed, motionless, not frowning, but not smiling, I know something's wrong.

I sit beside her and kiss her. "What's up, Haf?"

She doesn't look at me. "I have to tell you something."

My insides erupt. I'm afraid.

I'm afraid her feelings for me were just a frittle in her heart and now she wants to end what we have before I even have the chance to tell her I love her.

"Tell me," I say. I try to sound brave, but I fail.

"My mom," she says. "She's a Remade-American."

"Oh," I say. "I didn't know Cambree wasn't your real mom."

"No, Hadley. Cambree is my real mom. She's a Remade-American."

"Oh god... I'm so sorry. When did this happen? I saw her last week."

"No, Hadley. She was a Remade since before she married my dad."

"Oh."

"I'm a Remade, Hadley."

"But..." I can't think of anything else to say except, "You don't look like one of them."

"One of them?"

"I'm sorry. I..."

She looks at me now. "I should've told you before we started going out, but... I liked you so much. I wanted you to get to know me first before you... you know... decided."

"Oh."

"I told myself that I wasn't lying to you, because I never said that I was alive, but keeping this from you was deceitful and I'm sorry. I understand if you're angry at me. I'm angry at me too."

"I'm not angry," I say, and that's true. I'd have to be feeling anything to feel angry."

"I don't know if that's a good sign or a bad one," she says.

"Me neither."

She puts her face in the bowl of her hands and makes crying sounds. No tears come out, obviously.

I almost put my arm around her, but I don't.

"I can't keep living this way, Hadley," she says. "I'm a Remade. I'm tired of hiding it."

I want to tell her, "Don't worry."

I want to tell her, "I'll love you no matter what."

But I fail.

I thought Hafwen was happy before. But she tells me she wasn't. She says she was smiling on the outside and crying on the inside.

Now, she cries a lot.

Now she's pale, because she's stopped wearing makeup. She's cold, because she's stopped wearing heated clothing. Her hair is white, because she's stopped dyeing it. She looks dead, and says she's the happiest she's ever been.

I should be happy for her. Instead, I keep thinking about how someone else used to inhabit her body. I can't look at her the same way anymore.

She's used.

Second-hand.

Impure.

She says a lot of Remade girls try to pass for living, because they're ashamed of who they are. They buy into the whole natural is ugly paradigm. But natural isn't ugly, she says. Death isn't ugly.

Whether she's right or not, I don't know.

If there is a beauty in death, I don't want to see it.

I hate death. I hate that my mom died of thirst in a ditch on the side of the road. People drove by, but they didn't see her. They didn't hear her. Now when Hafwen stands right in front of me, I try to look through her. When she talks to me, I try to tune out her voice. Deep down, I know she doesn't deserve this kind of treatment. I also know that Porter doesn't deserve the beatings I give him every Tuesday morning.

I just don't care.

"Animal brains have to be illegal," I say. I say it with conviction, but I don't really know what I'm talking about. I defend the living and the systems controlled by the living only because doing otherwise would feel like a betrayal. "They're a gateway to human brains."

Hafwen laughs. "You really think there are hordes of Remades out there feasting on the brains of the living?"

"I don't know," I say. "It could happen."

"Hadley, animal brains are illegal because Remades eat them. They make us feel good."

"Have you ever eaten any?"

"No, but that's not the point. The point is, prisons are filled with Remades, and most of them are there just because they've eaten animal brains. The government sells these prisoners to corporations to use for manual labor, and every living person involved makes a lot of money. Doesn't this seem wrong to you?"

"I guess," I say. "But you have to admit, violent Remade crime is a big problem."

"If you read the statistics, you'd know that violent living crime is an even bigger problem. It only seems like a Remade problem because the media publicizes Remade crime a lot more often. A lot."

"I don't want to talk about this anymore."

"But we are talking about it, Hadley. It's important to me."

A few days ago, Hafwen told me the story of her parent's divorce. I expected her to say that her mother lied about being a Remade, and when her father found out the truth he left her.

But that's not how it happened.

Her father, Barry, knew her mother was a Remade from the very beginning. He was an activist for Remade rights and that's how they met in the first place. He loved Cambree and he wanted to start a family with her. So they had a baby. Her name was Bronwyn. Since she was born from a Remade mother, Barry and Cambree knew that at any time she could pass away and be Remade with a new personality. This happened when Bronwyn was 19 years old. Barry loved Bronwyn, and refused to connect with Hafwen in any meaningful way, and all the while he blamed Cambree for his daughter's death. One day he left for work and never came home again.

Now, this story buzzes in my head. I know that Hafwen's just looking for some living person to listen to her. To understand her. To say, "You're right. These things are very unfair."

But instead I say, "I'm going to bed."

This is our coffee-shop, Hafwen's and mine. Neither of us drink coffee but we enjoy the comity and the photographs of dancing mannequins on the walls.

Today, I don't invite her. I've never seen a Remade in here before, though I tell myself the reason I don't call her is because I need some alone time.

A man and a woman at the next table converse in loud whispers.

I stare at my book like I'm reading.

"I'm no racist," the woman says. "But they have no legal right to be here."

"I say send them back to where they came from," the man says. "Start paving all the cemeteries and let that be the end of it."

At least I'm not them. I don't want to get rid of the Remades. I'm all for equal rights. Hell, I'm even dating one of them.

I'm not a terrible person. So why do I feel like such a monster?

Minutes later I'm in my car making a call.

"Porter?" I say.

"Yeah," he says. "Hey, man."

"Do you want to hang out?"

"Hang out?"

"Yeah. We could go bowling or something."

"I hate bowling."

"Whatever you want."

"I don't know, man. I don't usually hang out with clients."

"Come on."

"Alright."

Fifteen minutes later, and I'm in a Remade bar. My mind spins, but I still notice that this is a shitty place. Like it hasn't been cleaned since it opened. Maybe that's true.

The waitress, who's either a living person or one of those Remades who buy into the natural is ugly paradigm, hands me my chai, and gives Porter a wad of tin foil.

"Thanks, man," he says to the girl.

She smiles and walks away.

Porter unwraps the foil.

"What is that?" I say.

"Brains," he says.

"I know that. I mean, what kind?"

"Human."

"Oh." I swallow.

"I'm just fucking with you, man. They're pig. Want to try some?"

"No!" I'm louder than I expect.

"Calm down, man."

I try.

Porter nibbles at the brains. He trembles.

After a few sips of my tea, I say, "Is it really so bad being dead?"

"What do you mean?" he says, gazing at his hands.

"I mean, why do so many Remades eat brains? Is it such a horrible existence?"

"No, man. Being dead is cool."

"Then why do you eat brains?"

His expression changes to one that I've never seen on him before. It's one of the looks my mother used to give me, when she was disappointed in me, but showed sympathy at the same time. "Figure it out yourself, man," he says, very quietly.

"Fuck you!" I say, standing.

"Let go of me."

I realize my hand is squeezing his arm. My other hand, it's in a fist.

"I think you should go, man," he says.

Part of me wants to stay and beat the non-living shit out of him. I want to blame him. Not just for how I'm feeling right now, but for everything. My mother's death. The state of the world.

Everything.

Instead, I release him and say, "Yeah."

Say you're lost in the orange groves behind your apartment complex because you're not ready to go home again, and you find three guys dragging a tied-up young woman toward a hole in the ground, with three shovels nearby. They're alive and she's not. You tell yourself that if they were dead and she wasn't, the scene wouldn't be so disturbing, because it's supposed to be the dead who do things like this. Deep down you know that's not true.

You think, "Get your fucking hands off her."

Say all of this happens. You'd be here too, like me. You'd crouch down behind the nearest trunk you can find, waiting and watching, with a wrenching knot in your gut.

For a moment I consider racing out into the clearing, bellowing and swinging my fists. But these guys, they're not like Porter. They'd fight back. They'd kill me.

So I watch them bury the poor girl. I listen to her muffled screams.

They dump her in the hole and start shoveling.

They say things like, "You like that dirt in your face, don't you, bitch?" and "Fucking zombie whore."

I try to study their faces, so that I can identify them later, but it's so dark. And I'm crying too much.

When they finish with the dirt, they pound the backs of their shovels against the grave, over and over and over. They laugh, and high-five.

Finally, they leave.

I dive onto the ground and start digging with my bare hands.

What I'm uncovering isn't just a young dead girl.

From deep within myself, I pull out a truth that I've always known but never wanted to admit. Remades don't eat brains because of the pain of being dead. The real pain comes from how the living treat them. How I treat them.

I pull her out of the hole. I remove the gag.

She looks at me with fear in her eyes.

I'm afraid she's going to scream.

I'm afraid she thinks I'm one of them.

But her face changes. It's one of the looks my mother used to give me, after I did something bad and then made things right. "Thank you," she says, very quietly.

I put my arm around her, and in my heart I'm embracing Hafwen at the same time.

I see her when I close my eyes. She's beautiful.

I'm ready to go home.

The Traumatized Generation

MURRAY J.D. LEEDER

Land sniffed at the air. He felt a kind of peace out here, so different from the city thick with industrial fumes and soldiers. The prairies sprawled in every direction, wilder and more overgrown than they had been in more than a century, and the Rockies were lost in a pink haze to the west. All of it sent Land back to a childhood spent traipsing around the countryside, when he didn't need to be worried about what might be hiding in the wheat.

He rapped on the front door. Eventually a woman answered in her nightgown, slightly older than him, and glowering. She knew what was happening, and Land's heart sank when he realized what he was about to do.

"Mrs. March? I'm Michael Land, Paul's homeroom teacher. I'm here to pick him for today's..." He hesitated. "Today's field trip."

"I didn't give permission for any field trip," she snorted, and Land put his hand against the door to stop her from closing it.

"I'm afraid the school board doesn't require parental permission when the field trip has been made mandatory by the government of Canada."

"The government," she said. "You mean the military, don't you? Either way, I'm not about to send my son away to be traumatized by your bloodshow."

"Mrs. March," he told her. "In that car is the sergeant they sent to escort me up here. If Paul doesn't come out of this house in ten minutes, she'll have to come and talk to you herself. Nobody wants that."

There was desperation in her voice. "Mr. Land, you and I remember a time before the military controlled our lives. You're an educator... how can you stand idly by and–"

"Just get your son, Mrs. March. Please. Just get Paul."

Mrs. March breathed in deeply. "Wait here," she said. "I can't believe I'm doing this."

She returned a few minutes later with the round-faced, serious little boy, dressed in unfashionable garments that made him a target for jeers too often.

"It's good to see you, Paul," Land said, and the boy half-smiled up at him. Land knew the boy all too well–smart, shy, sensitive, and far too vulnerable for this world. Just like the young Michael Land, back when CNN reported that the dead were rising from their graves.

The car door opened and Sgt. Hazelwood walked over to the door just as Paul was slipping on his coat. She was blond and beautiful but Land disliked her intensely. She was just the kind of rhetoric-spouting career army type that Land had encountered too often during his own tour of duty in Alaska. "All ready to go?" she asked, wearing a false smile that Mrs. March did not return. Ignoring the sergeant's presence, Mrs. March dropped to her knees and embraced her son.

"Remember not to be too scared," she said, and Paul nodded uncertainly.

"Do something for me," Mrs. March said to Land. "Promise me you'll sit by him. Try to keep him from being too scared. He has a weak heart."

Land nodded; before he could speak Hazelwood interrupted. "Then we'll just have to strengthen up that heart a bit," she said, ushering the trembling boy toward the car.

As Land looked back at Mrs. March he wanted to gaze into her eyes and assure her that everything would go all right, whether it was true or not, but found that he couldn't do it.

~

The huge chain-link fence encircling Calgary was intended to keep the zombies out, which it did, but it also served to keep the people in. The rule of law didn't need to enforce this, for few wanted to leave. Officers waived Sgt. Hazelwood's transport through the military checkpoint at the city's north gate. They continued down the vacant Deerfoot Trail, bound for the Saddledome. In the distance Calgary's downtown was silhouetted against the morning sky, postcard pristine, like a snapshot from Land's childhood.

Paul was quiet the entire time. His parents certainly taught him to avoid talking to anyone in a uniform. Land felt like he was ferrying a prisoner to an execution. He always hated this day, the worst of any school year. Nothing he'd seen up in Alaska bothered him half as much as the sight of ten thousand schoolchildren screaming for gore.

Yellow school buses dotted the Saddledome's parking lot, and Hazelwood weaved through the crowds of kids before they found Mr. Land's grade-seven class. Land hoped they'd arrive first, to spare Paul the humiliation of arriving under military escort, but no such luck. Built for the 1988 Olympics, the Saddledome had served for years as sports arena and concert venue. Now the military had appropriated it and remade it into their modern-day Coliseum.

"You get out here," Hazelwood said. "I'll go park in the barracks and join you inside."

"What?" Land said. "Isn't your duty here finished?"

"No." The sergeant flashed him an unreadable smile. "I'm with you for the whole day."

Land coughed in disgust. She probably thought he'd let Paul slip away from the show at the first occasion. She was probably right.

The rest of the class caught sight of them as they stepped out of the military vehicle. Land saw Bruce Tomasino say something to Jason Barrows, and they sent their whispers all along the line.

"Don't worry about them, Paul," Land said softly. "Just take your place in the line."

His student dutifully shuffled over to the uneven row of students. Land addressed them: "I don't want to see any shoving or shouting. When we get the signal, I want us to go in a straight line inside and take our seats. Any questions?"

"I got a question," asked chubby Jimmy Schwab. "Is it true... I mean, we heard a rumor that Zombie Bob will be here."

Please, no,Land thought. That would make it even worse; the presence of a TV celebrity would change this field trip from a military demonstration to a rock concert. Robert Smith Harding went with a camera crew behind the lines in lost cities and in infested countryside, found zombies and inevitably killed them in daredevil ways. His weapons of choice ranged from a jackhammer to a katana. The kids loved him, wore his picture, talked about him constantly. Land watched Paul's face grow grimmer still at this news.

A whistle blew somewhere across the parking lot, and the rows of students started proceeding up the concrete stairs and into the Saddledome itself. A uniformed officer waved Land's class ahead, and he took up the end of the line to watch them keep their course. Amid all the noise of kids gabbing away, he could barely hear Bruce and Jason talking about Paul. He made out one sentence: "That corpse-hugger's going to wet his pants when he sees this."

Land was always impressed by how little the Saddledome had changed since his childhood. This wasn't a real surprise; though the military owned it now, it was still a sports arena of sorts. The floors were still sticky and the plastic seats still painful. The Jumbotron was still there too, leftover from hockey games. Now it flashed messages like "ENJOY THE SHOW" and "THIS IS FOR YOU KIDS."

The most visible changes were the sideboards. The protective glass now went up much higher than in the old days, and they needed to be cleaned of splattered blood and brain meat nightly. As usual, the arena was covered with a layer of freshly tilled dirt. At one end there was a raised platform with a few microphones, and at the other there was a black velvet drape, which hid the zombie cage. A trained crew with cattle prods were ready to send the zombies into the arena on cue.

When the students took their seats, Land called for Paul to come sit with him by the aisle. He'd wished he could have done this more subtly–Paul didn't need to be a teacher's pet on top of a zombie-lover–however, he did agree to sit with the boy. As the other students chatted away, he asked Paul: "What do you think of all this?"

"I don't know," the boy said. "I've never been anywhere like this before."

"Your parents didn't want you to come here," Land said. "You know that."

"But they made you get me."

Land nodded. "The military thinks it's important that you be here."

"Why?"

The question caught Land by surprise. It was a good question–why? Why did one child deserve all this special attention? He stammered, searching for an answer, before one was provided.

"Because someday you'll be called to the service, and we think it's best you know what it's all about." Sgt. Hazelwood stood in the aisle, grinning down on them both. She had changed from her green field outfit into a brown dress uniform that accentuated her curves.

That's not a real answer,Land though, but he couldn't say anything here.

"Got room for one more?" Hazelwood asked.

Land looked at the empty seat next to him and tried to think of an excuse to keep her from sitting there, but could not. "Sure," he said. "Have a seat."

"No." She shook her head. "You sit there, and I'll sit on the other side of Paul."

Land wanted to protest but thought better of it. He stood, and as she slipped past he felt her body against his, her holstered pistol rubbing against his thigh.

She took her place next to the boy and smiled at him. "Your parents don't let you have a TV, do they?" she asked.

Paul shook his head.

"Then you don't know who Zombie Bob is?"

"Well, I know who he is because the other kids..."

"Oh good," she said. "It just so happens that I'm a friend of Bob's, and after the show I could take you to meet him backstage."

"Well," said Paul, "I don't really know if..."

"Just you, out of all these kids." She gestured at the thousands of schoolchildren around them. "That could really help you could make friends, Paul. They'll want to know you for sure after that."

Land shot her a disapproving look, but she only grinned. Fortunately, the lights began to dim. He heard Hazelwood whisper "We'll talk about this later" as a hush settled over the Saddledome.

A spotlight sprang into life, illuminating a lone figure on the platform. It was a silver-haired man in a brown dress uniform, metals dangling at his pocket. His image appeared a thousand times larger on the Jumbotron above.

"Howdy, kids," he said. "I'm Colonel Patrick Simonds. I recently got back from directing the troops on the coast, and the top brass said to me, 'Pat, you've done such a great job in Vancouver. When you get back, just you name it and it's yours.' And I said, 'I want to be the one who talks to the kids at the Saddledome."

Simonds wore a politician's smile he was never seen without. Affable and grandfatherly, he was just the kind of public face the military needed as it pressed its endless, costly war against an enemy that neither thought nor planned.

"Yup," Simonds, went on, "that's my favorite duty, because it's so important for the future. Once we recapture Vancouver and Toronto the real challenges will be open to us. New York, LostAngeles..." he paused briefly as some of the audience chuckled at the popular pun, "maybe even London, Tokyo. That's where you kids will be fighting the zombies. You should think of this day like a 'thank you' in advance. I think the very least we can do is show you how to do it."

Another spotlight suddenly cut through the darkness, lighting the black drape at the opposite side of the arena. Out stumbled a putrescent walking corpse, flailing its arms and awkwardly making its way forward. Its jaw was slack, its tongue lolling out in anticipation of its next meal. A collective sigh filled the arena.

"Look at it," Simonds said. "I bet this is the first zombie most of you kids have ever seen. That says something about how far we've come. It's hard to imagine, but there was a time when zombies even walked the streets of Calgary. But thanks to the vaccine, developed right here in Canada, none of us will ever be zombies. Remember that: kill a zombie, and that's one closer to killing them all.

"That disgusting creature you're looking at was somebody's brother, father or son once. I'm not going to lie to you about that. But he isn't no more; in fact, he's not a heat all, but an it!"

The colonel pulled his service pistol from its holster and carefully aimed at the brightly lit target, before firing. It sounded little more potent than a cap gun, but Paul twitched in his seat anyway. The bullet struck the zombie's shoulder, and it barely even noticed as it kept shambling forward.

"Ah, I didn't quite get him, did I?" Simonds said. "I've seen zombies lose all their limbs and keep on going. Their brain and their hunger drives them forward. They want to eat our flesh. That's all they want. And they never hesitate before they strike."

The zombie lurched steadily forward, having made it almost halfway to the podium. Many children clenched their teeth with the tension, but Land knew it would take a minor miracle for that zombie to actually reach the colonel.

"Now," said Simonds, "some people say, because these things were once our loved ones we shouldn't kill them. We all know people like this. These zombie-lovers think zombies are trainable–maybe we can toss them the odd steak to keep them happy, and teach them to fetch our slippers. But I challenge anyone to look in the eyes of the dead and see anything worth saving. Fellas, can we focus in on that?"

The Jumbotron zoomed in until the zombie's twisted, drooling face filled the screen.

"No life. No intelligence. In humans we see some kind of spark of life; I don't know what it is, but it's always there. You don't see that in zombies. That's what zombies are: humans minus a certain spark, and that's what makes them a perversion in the face of God. There's only one thing to do to them!"

Simonds fired again. This time it struck the zombie square in the head, a perfect killshot. There was a splash of bright red blood, and the creature fell. The Saddledome erupted with cheers and shrill whistles.

The house lights came up. "Pretty cool, eh?" Sgt. Hazelwood whispered to Paul.

"Now before I bring out a very special friend of mine," Simonds said, "we should all rise for the singing of our national anthem." An organ started up with O Canada; as they stood Land extended his arm behind Paul's back and nudged Hazelwood.

"Sergeant," he whispered. "We need to share a word outside."

"But Mr. Land, it's disrespectful..."

" Now," he said, just a little too loud, and he started away from the arena. She placed her drink at her feet and stomped after him. He led her outside, right onto the Saddledome's front steps, and there she began to snap at him.

"Who do you think you are that you can–"

"Who do you think you are to mess with my student like that?" Land shouted back at her. "God, a military pick-up, you hanging over his shoulder... Do you think this isn't hard enough for him anyway? The other kids will never let him hear the end of this."

"Good," Hazelwood said. "I don't want him to forget today. I want him to be traumatized as hell. He'll thank us for it later."

"When? When will he thank us?"

"When he's been dropped in some hellhole and told to kill." There was an absolute conviction in her voice.

"He'll be a man then, and better equipped to handle it than these kids are," Land argued. "Listen to them: they're whistling and cheering! It's just a show for them. That's just how you want them. They don't consider things. They don't think about things. The military doesn't want them to. I don't know who's more brain-dead, zombies or soldiers."

"How dare you!" Hazelwood cried, her throat hoarsening. "This isn't our world any more! It's theirs! We let our guard down, and they tear our throats out! Society mustbe prepared, prepared in every way, for war! It is the only way!"

Land shrunk back at the force of her argument. "Do you remember," he said, his voice cracking, "when they used to say that watching violent movies was desensitizing, and that was a bad thing?"

For a long time there was silence, and then Hazelwood said, "You've been wondering why there's so much special treatment for this one kid? What makes him so important?"

Land nodded.

"That was my idea. When I heard about Paul from your school's liaison office, I thought about the way Iwas before the zombies: a quiet, rural life. No TV. I'd never even witnessed violence. Then I watched a zombie tear my father's head off while he was working the fields. You know what I did? I didn't run, I didn't scream–I just shut off. The shock almost killed me. But that made me who I am."

Hazelwood was trembling slightly. She clenched her fists where she stood to steady herself. "Maybe you're a zombie-lover too, but you earned that right by fighting for your country up in Alaska. Mr. and Mrs. March never served, but their son will have to. Maybe it was noble once to be a conscientious objector, but now it's lunacy. The more they shelter Paul, the more they try to protect him, the more harm they do.

"I know you have stories like mine. We all do. We are the traumatized generation. A bit older and maybe we could have been better prepared for what was happening. A bit younger and we'd never have known a world without the zombies. If we are to spare the new generation what we went through, they must grow up impervious to trauma. Understand me. I value innocence. That's what Paul is. But in this world of ours, innocence kills." There were tears in her eyes. "It seems wrong, I know. Sometimes I spend whole nights crying into my pillow. But it's the only way. Let them cheer when zombies die. Better they cheer than scream."

Land turned away from Hazelwood and gazed at the skyscrapers of downtown Calgary, built so many decades ago, standing there like silent memorials to a dead world. "I wasn't made for these times," he said.

"None of us were," she answered.

Land wiped his eyes and turned back to face her. "They've probably brought out Zombie Bob by now. We should get back to Paul."

"Yes," Hazelwood agreed. "He needs our support."

Inside, the Saddledome pulsed with rock music. Land recognized the Doors' "Peace Frog," which, thanks to the tastes of a certain general, became something of a military anthem. To its steady beat Zombie Bob, dressed in full western garb with a white Stetson, wove his way between ten or so zombies, a roaring chainsaw in his hand.

It was part of Zombie Bob's appeal that it seemed like he could die at any moment.

Colonel Simonds was still on the platform, now protected by a half-dozen guards with submachine guns, offering commentary as Bob played the clown, always making it look like the zombies were just about to get him, before getting them instead.

"Careful Bob, there's another deadhead behind you," said Simonds. Bob did a cartoon-like double-take and slid the saw around to his back. Then he slid backwards on the dirt, driving the saw through the hapless zombie's midsection. Bob did a pirouette, slicing the zombie mostly in two before slamming his weapon right through its neck. A thick plume of blood shot out.

Land winced at the display. No one he had known in Alaska would attempt anything remotely like Zombie Bob's antics. He and Hazelwood slid back into their seats on either side of Paul, and Land asked the boy, "How are you doing?"