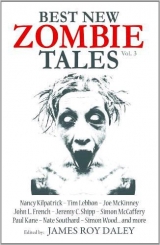

Текст книги "Best new zombie tales, vol. 3"

Автор книги: James Daley

Жанр:

Ужасы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 16 (всего у книги 20 страниц)

For Razor, it has always been satisfaction. Circumstances have only magnified this desire, altered the means by which his satisfaction is achieved. Now, satisfaction means escape, running away, hopping on the metaphysically mutated freight train raging through his body. He vaguely remembers some ancient classic rock performer's nasal bleat and cackle: All Aboard !

Razor uses the needle end to roll the cotton ball around, making sure to get everything. He puts the flat end of the needle on the cotton ball, drawing the plunger back. He raises the syringe to eye level, admiring the yellowish color. He pulls down on the plunger again, taps the syringe with his forefinger, and watches the bubbles rise. Sweat trickles down the sides of his face. Razor firmly presses the plunger back up. He clenches and unclenches his fist, tightens the belt around his upper arm. The veins protrude like mountains on a relief map. The needle pierces flesh. Razor gets the register; he is perfect as always: blood flows into the syringe. He inhales and exhales, emitting an audible sigh of pleasure.

Now: Razor presses the plunger, slowly ( teetering[patient])–Hold it ( this is better than ),hold it ( any heaven they ... who are they ?),hold it ( could promise ),pulling back on the plunger ( in the afterlife: 1. death 2. hunger ...),jacking off (that's what Metal Fred called it, milking the high, lingering before surrender: teetering...), so good, so good... pressing in again, fully, the freight train in overdrive ( All Aboard! Hahahahaha ...)–Pounding on the door– shit, the cops–yanking the needle from his arm–

SHITSHITSHIT! (pounding–no, wait– scratching... )

derailed by paranoia, by...

( scratching ?)

cops?

~

eyelids

quiver in defense

light streaming in like sandpaper ( abrasive–WAKE UP!)

SOUND: scratching at the door, muffled pounding– the cops? Confusion. Why don't they say something? Why don't they –( WAKE UP !)

There are no dreams, only memories... and Reality !

The door splints from the pressure. They– the dead–slowly shamble through the opening; a throng of arms and legs and gaping maws converge to fill the allotted space. Like excrement forcing its way through an ever-widening sphincter, the bodies fill the doorway with disregard toward everything but the purpose at hand: the acquisition of food. They are scavengers driven by the hunger. That is all that they are.

Rubbing his eyes, Razor back-peddles on his rump to as neutral a corner as possible, gagging on their abhorrent stench. His eyes are watery but clear, lucidly soaking in the true Reality manifesting before him. A Reality he had so tried to avoid... to escape from...

The dead, in all their revivifying glory, tear the baby– what was her name ?–to pieces, clutching and yanking with selfish fingers more akin to vulture's talons. Eyes glazed like slivers of shattered stained-glass hope, patches of skin gray with putrefaction... if there is any skin at all; they are nothing more than the urge: to feed. This point is made abundantly clear by the constantly flexing jaws, chewing air, in desperate search of meat. And when meat is procured, momentarily sated by a fistful of flesh, stringy entrails, or once vital organs: grist for the bone mill.

Sara's scream cuts through the monotony, a jagged, agonizing wail, much like the rotting teeth that penetrates her flesh and unconsciousness. Razor cringes, impotent to react, eyelids slamming shut, fingers plugging ears, trembling. It is not as if he cares; his body coils inward–closing himself off out of a learned, well-oiled reflex of denial. She squirms, but already too many bony fingers dig into the freshly excavated cavity in her abdomen. They scoop her intestines into their dust dry mouths, sucking as a child would on a plate of spaghetti. Her farewell refrain is a gurgling confirmation of participation in the ultimate physical travesty: to be eaten alive, a violation beyond reciprocation. The gurgling coda is eclipsed by one of the androgynous dead–gender and genitals having been withered by the passage of time–as it chews her tongue right out of her mouth.

When Razor harnesses the courage to open his eyes again, it is to the same bleak scenario that closing his lids had blotted out. With dull, machine-like precision, the dead continues to strip the last of Sara's meat from her bones, slurping the final droplets of blood from the hardwood floor. Some even suckle on her clothing–much as a baby would its mother's bosom–drawing blood from fabric, or possibly even sustenance from the very scents that lingered within.

Razor whimpers. It's all his body can muster as a response to the cruel play before him: an improvisation of insanity. All he wants is to be away from this ramshackle theater of the macabre. It, too, is a violation beyond reciprocation, a reiteration of the reality in which he is trapped. Scrunched into the corner, he wishes he were wood, wishes he were able to blend into the wall. His eyes flicker to and fro, still looking for a means of escape... when he spots one.

It glimmers, a winking reflection of light, a light at the end of the tunnel: the hypodermic syringe. Equidistant between the gorging horde and him laid the needle. Naked and singing, singing to him !He instantly becomes transfixed on it, focusing to a point of blocking out the madness. The bogus barrier his mind creates gives the impression that it had eradicated the obscene exhibition, bringing down the curtain, but not in the purest sense. He can still see them, but now it is as if they are behind a TV screen–their usual mode of intrusion, cameras poking out of windows, or on top of buildings, peering down on the deluge–their heinous acts being transmitted from some place far beyond the confines of the studio apartment. They are real– TV never lies–but are no longer his immediate concern.

Razor crawls toward the syringe, oblivious to everything but the hypnotic lure of the needle. A needle that serenades him with promises of escape, of attaining the state of sweet nothingness he so covets. As his fingers pluck the syringe from its solemn resting place in the middle of the room, his wrist is roughly accosted by one of the dead. Illusory TV screens melt into pools of stark reality. A gasp squeaks from his larynx, a gasp of shock and futility. Worse than the cold, bony grip on his wrist, though, is the revelation within the syringe: it was empty. The promises it tendered, all counterfeit.

So why was it still singing?

Razor breaks free from the skeletal grip, breaking a couple of bony fingers in the process, scampering rat-like to his corner. But it is too late. His scent is the only enticement they need as they crawl and stumble toward him. Intoxicated: caught in the forever feeding frenzy.

He jabs the needle into his arm. Something sharp to set him free– that is all he ever wanted anyway–but nothing. Again he jabs, repeatedly puncturing himself, ripping many holes like tiny, lipless mouths, lipless and laughing ( HAHAha)... They all laugh ( HAHA), drowning out the spiking pain. (Drowning...) Blood trickles like crimson streamers, decorating his arm with the appropriate attire indicative of the sullen celebration. Disillusionment blossoms on his face; a serrated slash devoid of verbal release blooms from his mouth. He continues to assail his arm with the needle; many more tiny, lipless ( mocking) mouths join in the chorus of laughter ( HAHAhaHA-HAHAhaha) that fills his head. The dead paws him, and swiftly indulge. Razor is impervious to everything but the morbid quest at hand, desperately jamming the needle with vicious intensity into his now mutilated arm, knowing full well that death is near–its imminence assails his nostrils, dulls his brain, his motivation quickly disintegrates into listless, automated repetition–and not wanting to face it. Not realizing that in death he will finally be set free.

( HAHAhahaHAHAHAha...)

~

"...as another day comes to a close, my friends, another day like all the rest, accumulating as scratch marks on the wall. I can only hope your day was as uneventful as mine. A tepid plea, I know, my friends. After all, misery loves company, but suffering is integrated into our very souls, woven into the very fabric of each of our lives. A neck within a noose– waiting..."

Memory Bones

MICHAEL STONE

The sickly butcher's shop smell got stronger as he ascended the stairs. The carpet stuck to his feet.

"It be the bedroom on the left, Doctor."

Messinger turned to acknowledge the speaker but he had already ducked from view. He muttered his thanks and continued up the stairs, his Gladstone bag bumping against his leg. A dust-dimmed window let in just enough light for him to make out two doors, one on each side of the tiny landing. He pushed open the door to the left.

The room stank of open wounds and wet bandages. Wrinkling his nose, Messinger peered myopically into the darkness, trying to discern edges and corners in the flat grayness.

"You must be the doctor."

Messinger faced the voice and a bed coalesced in the gloom. "Ahh. Mr. Lode, I presume." The attempt at humor didn't bring any response. He asked politely if he could draw back the curtains. "I need to see you if I'm to examine you."

"Aye." The speaker sounded hoarse. "If you must. It's just that my eyes are very sensitive at present."

"I shall take a look at them in a moment, Mr. Lode." He parted the heavy drapes to let in a chink of light.

"That's enough! No more than that."

There was just enough sunlight for Messinger to see a man propped by pillows, his body hidden by a high-collared, ankle-length nightshirt. The doctor smiled wanly. The nightshirt looked to be the source of the bad smell that pervaded the room. The patient's age was difficult to determine–his hair was as thin and colorless as melting snow, but his long face was unlined, the skin around his jaw smooth and tight. Lode's pupils were pinpricks in pools of baby blue.

Messinger sidled to the bed and eased himself down, placing his Gladstone bag between his feet where it clanked on a bedpan. It was then he noticed the scratches in the wall behind the bed: reminiscent of a prison cell, hundreds of short vertical strokes with a diagonal slash denoting groups of five covered an area of wall larger than the bed's headboard.

"So what seems to be the problem, Mr. Lode?"

"It's not me you've come to see, Doctor."

"Oh! I do apologize. I was told the patient was in this room. By your brother, would it be?"

Lode nodded. "Aye, he weren't having you on." Lode reached out and gripped Messinger's wrist. "You've taken over old Dr. Dimmock's practice, yes?"

Messinger nodded.

"Did he mention me?"

"No, but I didn't actually have the pleasure of meeting Dr. Dimmock. I was appointed by a selection committee after he retired."

"Pity. He was a good man, Dimmock. Open-minded. Are you a broad-minded sort of lad?"

"Well, yes, I suppose I am." Messinger tried to smile.

"Good, because I want you to listen to me. Right?"

Messinger nodded, although he felt things were far from right: Lode's grip was surprisingly strong.

The grip lessened and Lode settled back on the pillow, his blue eyes never leaving Messinger's. "How old do you think I am, lad? You won't find the answer in your notes so don't bother looking."

Messinger straightened up. "And why won't I find any mention of it in my notes?"

"Because your predecessor made up a name and date of birth for me, that's why. Like I said, he was a good doctor; I'm hoping you'll be the same. Now answer the question: how old do you think I am?"

Messinger considered arguing that Dimmock wouldn't have falsified Lode's details because of the minefield of National Insurance, NHS records, vaccination programs and the like, but decided to humor the man. Maybe that was what Dimmock had done; humored him. It was a fact that consultations went smoother once one had gained the patient's confidence.

Messinger's eyes were becoming adjusted to the dim and dusty light now, giving him a better opportunity to observe the patient's features: the unlined face and clear blue eyes that contrasted sharply with the thin hair and liver-spotted hands. "If I had to guess at your age, I'd venture that you're somewhere in your early fifties, perhaps."

Lode laughed. "Way off, lad, way off. Actually, I'm 149!" He laughed again, throwing his head back. Messinger noticed that his teeth were unusually small, very white and even. Lode's laughter snapped off suddenly as he looked squarely at the doctor. "You think I'm mad?"

Messinger gave a non-committal smile. "That's not within my remit," he said smoothly. "However, I'm a busy man with a lot of patients to see this morning, so can we stop playing around?"

"You ought to show some respect for your elders!" barked Lode.

The bed squeaked as Messinger pushed himself to his feet. He heard a corresponding creak on the landing.

Lode shouted. "It's all right, Eustace; the young man is not going anywhere!"

Messinger heard footsteps retreating down the stairs. Disquieted, he sat down.

"I amone 149 years old. When I was born, Victoria was on the throne and Britain was at war with Russia. Just accept that. I could verify it by telling you loads of historical details but you would dismiss them as mere fancies learned from books. My bones are as full of memories as yours are of marrow jelly, lad.

"When I was in my mid-forties–I forget exactly how old I was–something strange happened. I fell under a carriage. It ran straight over my arm here," Lode indicated a point below his left elbow, "severing it completely. I picked it up and ran home to my wife. Screamed my bloody head off, I did!" Lode chuckled at something he'd said before fixing Messinger with a searching stare. He shook his head. "Regular little doubting Thomas, aren't we, lad?" He rolled the left sleeve of his nightshirt up to reveal a thick, ropey scar that circumscribed his forearm.

Messinger peered closer. "There's no way they could have stitched your arm back on in the 1890s," he said. "They didn't have the know-how."

"Nobody stitched it on. It grew back!"

"Of course," Messinger sighed. "Silly me. It grew back."

"Don't get sarcastic, lad, I'm warning you."

"And what became of the arm? Did that grow into a pet?"

"I buried it in the compost heap."

"Pity, you could have hand-reared it."

Lode's lips tightened.

Messinger sighed. "You were saying, Mr. Lode."

By way of answer, Lode leaned forward and raised the hem of his nightshirt to reveal his knees.

Messinger recoiled. "Jesus Harry... who did that?"

"Eustace."

"The bastard must have used a lump hammer!"

"A sledgehammer, actually. Every other Thursday. He seems to think I might run away." Lode sucked on his teeth. "There are times when he might have been right."

Messinger jumped to his feet, unclipping a cell phone from his belt. He saw again the scratches on the wall behind the bed, and again he thought of a prisoner counting the interminable days of incarceration. The fives were arranged in columns of ten, and there were fourteen completed columns... making over 700. But 700 what? Days, weeks? Surely not months?

"If that's what I think it is, put it away, lad."

Messinger put the phone to his ear.

"If you don't put it away, I shall call in Eustace." Lode let the threat hang in the air.

Messinger shot a nervous glance at the door as a floorboard creaked, and felt the fight in him drain away. "Ah, sorry. Wrong number. Yeah, my mistake. Bye." He broke the connection.

"Now come and sit down." Lode patted the side of the bed. "Come on, lad."

He sat down. "But why–" he began.

Lode held up a hand. "All in good time, lad."

"But this is crazy."

Lode's face softened. "Aye, lad, I know I'm asking a lot of you." He looked at the doctor from under lowered eyelids and chuckled. "The best is yet to come."

"I can't wait."

"I'll ignore that. Anyway, Bessie and me, we kept the arm incident a secret. I lay low, hardly venturing out while the arm and hand were growing back. We nearly starved to death, with me not being able to go to work. Times were different then. That's when we started the vegetable garden, all the way back then."

Lode's eyes clouded over. "Bess died in 1919 of 'flu. Bloody terrible, that was. You young 'uns don't know you're born, I swear. We weren't any more able to cope with grief then as you are now, you know? Just because folks lost babies to disease and brothers and husbands to war, it don't mean we became immune. I was one of twelve children. Only eight of us reached adulthood. My mother used to keep daisies in four little jam jars. 'One for each of my little mites in Heaven,' she used to say.

"But when Bessie died, I don't know, I just couldn't cope with it. I was an old man, what did I have to live for? In the end, I went down to the Cotton End Bridge." Lode indicated behind him with a thumb. Messinger realized the man was referring to a bridge over a railway line that had served the local collieries. The track was long gone. He hadn't even known before now that it had a name.

"And?"

"I threw myself under a goods train. When I came to, I couldn't see. I was blind." He looked at Messinger, obviously checking that he was paying attention. "I staggered for a short distance and then gave up and lay down where I was. I could tell by my sense of touch that I was among those tall weeds, the ones with the pink flowers."

"Rosebay willow herbs," supplied Messinger automatically.

"Right. And I could also tell by touch that my head was missing."

Messinger blinked, then slumped and covered his eyes. "Jesus Christ! You had me sucked into your crazy little world then. For a moment, I actually believed."

"And so you should," said Lode. "It's all true."

Messinger shook his head. "Oh no. You're not catching me out again. I'm off." He started to rise.

Lode grabbed his wrist.

"You're leaving without examining your patient? What sort of doctor are you, eh?"

"A sane one," he retorted.

"You think I'm insane? I've been crippled and bedridden since 1952; what d'yer expect? My only contact with the outside world is through Eustace." Lode's eyes flicked meaningfully at the bedroom door. He sat back, breathing heavily. "Please, lad. Stay a little longer."

Messinger sagged. He hated himself for it, but he wanted to hear the end of the story. He knew that all he had to do was peel back that high collar and examine Lode's neck, but he wouldn't–it would be an admission of gullibility. And on a deeper, more primitive level, he couldn't."Okay, but it's against my better judgment."

"Good boy." Lode patted the side of the bed again.

Messinger sat down obediently.

"My head grew back," Lode continued, "just as my arm had. I had no idea how long I lay there among them pink weed things."

"Rosebay willow herbs."

Lode took the correction graciously. "I recovered enough to find my way here and recuperated over a period of several months."

"Forgetting for the moment the sheer implausibility of you surviving decapitation and any subsequent regeneration," Messinger allowed himself a smile, "if what you are saying is true, you wouldn't have any memories. You had grown a completely new brain from scratch. You would, mentally, have been like a newborn. Your story has a plot hole I could drive a bus through."

"We pondered long and hard on that one, me and Dr. Dimmock. He suggested that as cerebral fluid surrounds the spinal cord, it could act as a repository of memories." Lode shrugged and spread his gnarled hands as if he really didn't care. "Anyway, while my body was growing a new head, my old head had been busy growing a new body. Eustace turned up. Eustace, like all my brothers, is me. A clone. It was Eustace that started to call me Mr. Lode. It's a joke, you see–I wasEustace Orr but now he is and I'm the lode. He keeps me crippled and when he wants another brother–"

"He removes your head and grows another. Brilliant! Can I go now please?"

"You are being very rude, Dr. Messinger."

"Frankly Mr. Lode, Orr, whoever you are, I think I'm entitled to be rude after all the crap I've had to take from you." Messinger grabbed his bag and stood. "I shall be sending for an ambulance as soon as I have left here, thereby discharging my obligations to you."

Lode raised a shoulder and let it fall, a one-shouldered shrug that said it was Messinger's loss if he left now. "Before you go, take a look out of that window, lad. Tell me what you see."

"What's out there, the tooth fairy?"

"Just look, will you?"

Messinger rested his hands on the windowsill and gazed out, blinking at the change of light. "There are a few old guys at the bottom of the garden. Weeding by the looks of it."

"They'll be tending the vegetables. We grow our own as much as we can. Look closer at them. Notice anything unusual?"

Messinger narrowed his eyes. He turned back to the man in the bed. He did a double take out of the window and then back at Lode.

Lode's smile was that of the cat that has found the cream. He indicated the scratches on the wall. "I have spawned 738 of us so far, with another on the way. And some of them have become lodes too, I daresay."

Messinger licked his lips with a dry tongue. "Why?"

"Why what?"

"Why would you want to create so many clones of yourself?" Messinger thought about what he had just said, and added: "That's assuming your story had a single grain of truth in it, which it doesn't, of course."

Lode laughed that bitter short laugh of his. "Haven't you ever dreamed of a world without divides? A world where everyone agreed with one another? One religion, one government, one mind; everyone living in harmony? Eustace has watched the world go to hell in a handcart, watched history repeat its mistakes–correction, he's watched peoplerepeat their mistakes. He's taking steps to put things right."

Messinger rubbed his eyes. "My predecessor must have been a gullible old fool if he went along with this lunacy. I'm leaving now, and when I get back to my surgery I shall remove the names Lode and Eustace Orr from my panel. As from this moment, you are no longer my patient."

"I've told you, it's not me you've come to see."

Messinger made a show of scanning the room. "So where's my patient?"

Lode motioned with his chin at a deep chest of drawers. "Top drawer," he said. "He's a slow developer, this one. We're a bit worried about him."

Messinger dropped the bag carelessly and crossed to the drawer in question. Glaring angrily at the heavy-looking brass handles, he gripped them tightly to still the quivering in his hands, his nostrils full of the almost overpowering stench of blood and disinfectant. On the limit of hearing he could hear a gentle sighing, a sound like a damp paper bag being slowly inflated. Was it the soft swish of his own blood pulsing in his ears, or the rhythmic rasp of raw, embryonic lungs pulling air? He whipped his head round and glared at Lode, sitting in the shadows... who grinned right back at him expectantly, his teeth a string of pearls in a peach-fuzzy face.

I have spawned 738 of us so far, with another on the way.

"Bullshit," Messinger growled. Annoyed with himself for even hesitating, he snatched open the drawer...

Going Down

NANCY KILPATRICK

Shortly after the Deadies got up to stroll the boards on Manitoulin Island, Paddy ran out of meds.

She'd been on largactyl for years–brain mangulations, dry gut ruttings, critical BO. The stuff stripped polish off floors and tasted rat-poison sweet so her insides undoubtedly resembled the arm of a kid she'd seen gnawed by a combine. She could've lived with that, though. But when everybody started coming back from the dead and chomping on everybody else, what was the point of taking drugs, even if she had any, with so much good film noir available?

Still, those asphyxiation-blue tabs had propped up everything crumbling inside her skull. Like the retaining wall that kept water from swallowing the land, her wall had worked pretty good most of the time. But nothing aired on TV anymore. Or radio. The movie theater closed. Her retaining wall was eroding fast.

Paddy opened Daddy's channel changer and twisted the wires so she could corkscrew holes in her wrist. The vein kept jumping out of the way and she ended up with ten round oozing bloodeyes. She sucked and tasted fresh flesh. Shit, she thought, now that the Deadies trudge the pebbles on the lakefront around the clock, nobody's left to ferry to the mainland. She'd seen all the videos and DVDs on the island. The pills from the drugstore might be gone, but residue floating in her blood stream still broadcast too loud and clear. Anyway, the second Marilyn Monroe got back, that signal would dim. Marilyn would like the Deadies, at least Paddy thought she would.

God knows, Paddy liked them. She'd tried to join their club before there was a club and if she'd done it right she'd have been a charter member. ODs. Hemp slung over the beam in Daddy's root cellar, where he used to lower his pants and pull down her... She'd dropped her eyelids once and the screen went blank. Marilyn's steady hand plunged the bread knife into her heart.She missed the projector and Paddy'd been pissed. Her lung felt like badly spliced videotape and that's all. Marilyn refused to visit Paddy the whole time she was in General Hospital. Paddy'd thrown a fit until they gave her more drugs and a new flat-screen TV.

Life had been tabula rasa with no chalk. But then the Deadies started. Right away Paddy saw they were luckier than her. They never worried about getting aced in the butt by stray emissions and they didn't have to memorize lines. Anyway, did they care why they were chained to this rocky poor-reception island, or wonder who would rip out their liver this week in 3-D, or make them sit in a hair seat and suck in a teen comedy then fuck them doggie style with blurry trailers, or any of the other stuff Paddy worried about all the time? All they thought about was grabbing somebody with their slimy green hands to snack on. She could handle that. She could be a Deadie.

But the Deadies didn't want Paddy. She stank wrong.

" It's an insult," Marilyn assured her when she finally deigned to visit. She waved a spotless silk hanky in front of her perfect transparent nose. Paddy was hurt until Marilyn said she had an idea.

" Shove your fingers past their cold black lips, into a living porridge mouth and let things crawl over your skin. Action!" Marilyn giggled.

Paddy tried it. No cracked molars clamped. No spoiled tongue licked. The switched-off eyes didn't flicker. "I'm not good enough for them," she whined. Marilyn slapped her silly and shrieked, "I told you before, diamonds are a girl's best friend."

Paddy felt iced as the black waters rose. The volume increased. Dense moisture plugged every orifice of her body like giant chilled-wax suppositories and the world slipped away on basic hypodermic steel.

Everybody she knew got to be a Deadie.

Everybody but her.

Meryl Streep, Tom Cruise, those anonymous B-zombie brats with mouse-turded hair and kiss-my-deceased-ass grins. Everybody on the island she hated, and that was everybody but Daddy. Even Marilyn got to chat with the Deadies at the Bus Stop and they listened like she emitted extra-terrestrial short waves, but she said it was because she was an Icon and closer to them than Paddy could ever be. That made Paddy real mad, especially when Marilyn signaled Daddy.

Nobody sent signals to her Daddy but her!

Paddy tore Marilyn's white arms, legs, and ears off, and pulled the blonde hairs out of her pube until she stopped broadcasting.

~

Paddy squatted on a boulder eating a double box of Twinkies and drinking warm Upper Canada Lager from the big tins. Two Deadies lumbered after Rewind, one of the last living dogs left. The collie belonged to the Woods, who used to run the video shop. As the three got closer, Paddy saw it was the formerly living Mr. and Mrs. Woods lunging at their golden-haired pooch. Rewind bounded like he was having fun. So did the Deadie Woods. To Paddy's camera eye, they made a nice nuclear family.

Man, she thought, life is incompletely unfair. All the two-dimensionals get everything and people like me who are the truly brilliant and can satellite dish every movie channel are relegated to minor sitcoms. How'd theylike to be inside out for a living? Life always tunes you out. It's depressing as hell. She swallowed a couple of Tylenol to the third power she'd found in Mrs. Soles' medicine cabinet. At least they had codeine in them and that was better than nothing, almost.

She chucked a pill-shaped stone at the stinky mould-grey water and it skipped across the surface. One. Two. Three. Three was the right button. She clicked on a Dolly Parton song, turning up the volume on the old tape player so she could masturbate in peace. The Deadies didn't notice. Mr. Woods had caught Rewind and they were biting each other, which was fun to watch, until Mrs. Woods joined in and blocked Paddy's view.

As Rewind howled, Dolly wailed about never gettin' what you need when you need it. Yeah, don't I know it, Paddy thought. Her body spasmed. Like killing yourself's easy. She wiped sticky fingers on her filthy shirttail and shoved another Twinkie all the way into her mouth. Everybody thinks it is but that just shows you what they know. If it was easy, everybody would have been dead before she was born and Paddy'd have managed it by now too.

Shit! She kicked dirt at Fat Eddie the Deadie as he passed. He ignored her, just like he always had. She wanted to be part of the Deadies more than she'd ever wanted anything. Maybe, when Marilyn came for her next visit, shecould figure some way for Paddy to get in with them, to make them see Paddy's dead potential. Dolly sang about possibilities. If only Paddy could be a Deadie, she just knew she'd be happy forever like Miss Dolly Parton. She closed her eyes.

" Take three hundred and twelve: Norma Jean to the Rescue!" Marilyn appeared half naked and boxed Paddy's ears good until she was bored. Finally the sex goddess grabbed the last Twinkie and admitted, "I've been working on a plan."