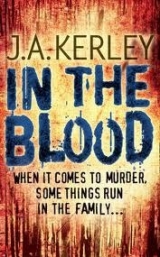

Текст книги "In The Blood"

Автор книги: Jack Kerley

Жанры:

Полицейские детективы

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 16 (всего у книги 20 страниц)

Chapter 39

We found Douthitt alone in a small employee lounge on the third floor, eating a bag of chips from one of the machines lining the wall. The room smelled like cigarette smoke. He was leaning back in a chair with his feet on the table, cramming chips in his mouth from his palm, licking it afterward.

“Where is she, Michael?” Harry said.

“Who?”

Harry’s hand lashed out like a cobra, grabbed Douthitt’s collar, pulled him to standing.

“The kid you helped kidnap.”

“I didn’t do nothing. Fuck you.”

Harry reached down and grabbed Douthitt’s long sleeve, pulled it high. Tats: eighty-eights and SS knives and a swastika on his forearm for good measure.

“You like them?” Douthitt sneered. “They don’t like you.”

I grabbed Douthitt by the arm and yanked him away from Harry before my partner could strangle him.

“Michael Douthitt,” I said, pulling out my cuffs, “you’re under arrest. Accomplice to kidnapping in the first degree. And one attempted kidnapping.”

I saw thoughts tumble through Douthitt’s head, calculations followed by puzzlement. And sudden fear.

“I didn’t do nothing but answer a phone call,” Douthitt said. “And not this time. Book me and I clam tight, call my lawyer. First-class, special-ordered, just for me. I’m bailed fast, out and laughing.”

What the hell did Not this time mean? And the bit about the phone call? I felt a prickle up my back; something was haywire.

I turned to Harry, winked twice. Our signal that I was about to go into Oscar-nominee mode.

“Give us a little time here,” I said, brusque, giving Harry an order from the Alpha Dog, showing Douthitt who was in charge. “I wanna get some things straight with Mike. Wait in the hall, wouldya?”

Harry did dumb. “Huh? What you gonna do with –”

“Beat it.” I shot a thumb towards the door. “Go grab a coffee an’ I’ll call you when I need you.”

Harry mumbled, slouched his shoulders, and sullenly shuffled away. Wentworth had mentioned that Douthitt wasn’t bright. A guy in his mid thirties making minimum wage pushing food carts? I figured the human resources director was right.

When Harry left, I went to the door and looked right and left as if making sure it was just Mike and me, two amigos, members of the same tribe. I closed the door and grinned ear to ear.

“I didn’t see you at Arnold’s rally last night, Mike.”

Douthitt’s mouth fell open.

“Jesus fuckin’ Christ. I was there. You was there, too?”

“Arnold is God,” I said. “I never miss a chance to see him. It was fuckin’ incredible, right? Arnold roaring in behind that Harley escort, speaking from high up on that van, the fire burning below. An inspiration to white people everywhere. And wasn’t that band the hottest?” I did few headbanger bows while singing “Fuck the spics.”

Douthitt grinned. “Goddamn…you really were there.”

Douthitt had been there too, pretty much nixing him for the grab. But he’d said something about “not this time”. Had he meant the abduction? The advance work? I checked the door again, leaned close to Douthitt.

“Lotsa guys on the force are sympathizers, Mike. I’m the one in charge of going to the meetings, bringing back the news. My pipeline to Arnold used to be Donnie Kirkson, but now I’m tied direct to Boots.”

His eyes widened as much as his gaping, gold-filled mouth.

“Holy shit!” he bayed. “Boots Baker?”

I winced. “Shhhhh!”

“Sorry.”

I sat beside him like a counselor, put my hand on his shoulder. “What went down last night, Mike?”

“Nothing, brother. I was as surprised as everyone else when I got to work today and heard the kid had been grabbed.”

“But the first attempt to snatch the kid…you were in on that, right? The inside man?”

“I got a phone call asking where the kid was. That was all.”

“You don’t know who made the grab last night? You being straight with me?”

He put one hand out, palm down, the other beside his head, like he was swearing on a bible in court. “I swear I got no idea who did the snatch. Not this time. Musta been someone else tipping them off.”

I patted his shoulder like he’d been a good dog. “You got your directions, right, Mike? For if you got caught?”

He tapped his wallet. “I got a lawyer’s number.”

“Call him, pronto. You’re gonna be fine. You gave some directions into a phone, talking casually, right? For all you knew, it was a parent or guardian, right? Getting directions to see the kid?”

Douthitt grinned, thinking I was feeding him lines. He shot some idiot damn Nazi-aryan salute.

I said, “You’re cool, brother, a non-participatory involuntary participantosa. It’s legal shit that means you were involved, but you had no malice aforethought.”

I walked to the door, opened it, peered out. Harry looked at me from a dozen feet away, making sure no one disturbed the conversation in the break room. I turned back inside.

“Tell me something, Mike. Why didn’t you make the grab the first time?”

“They wanted me to, but I wasn’t taking no chance of going to the pen for kidnapping. They said, ‘If you can’t get the kid out, kill it.’ I said, ‘Now I’ve got a murder charge. No way.’ A few days went past, they called and said they’d prepared some guy to do the grab – Bailes. All I had to do –”

“Back up. ‘Prepared’? Your word or theirs?”

“That’s what they said: prepared, like food.”

Bailes being prepped with the lie that he had terminal cancer? Bailes had been prepared, all right; cooked like a goose.

Douthitt continued: “Bailes called, said, ‘Where’s the kid?’ I told him how to slip up the back stairs to the fourth floor, the PICU. The kid was third in a line of five.”

“No calls after Bailes failed?”

“Nothing. I swear.”

I gave Douthitt a long side-eyed glance, like I was gauging his worth for the truth.

“The caller let you in on why the kid had to go, Mike? They told you the story, right? It’s scary.”

A pure fishing expedition. I wondered if Douthitt’s handler had given him a reason for Noelle’s abduction, or if he was an ideological soldier, an automaton.

“Oh wow, man, yeah. I heard the kid was something a doctor made in a laboratory, like a Frankenstein nigger or something. It was a threat to the movement and had to be stomped out.”

Frankenstein. The drooling wreck Spider had used that word. And similar ones, ending with the exhortation to destroy Noelle.

“You were checking the kid that day you rammed the cart into me?”

He nodded. “When I saw two cops, I banged my cart into you for a little fun.” He held out his hand. “No hard feelings?”

I took it, making a mental note to wash my hand in disinfectant first chance I had. “None, brother. You gave directions and that was it. Like I said, Inparticipatory involitudinal nonparticipitude. Or, as we say in the biz, ‘Scott-free’.”

I winked, put a solemn mask over my face, opened the door. Harry came in, cuffs already in hand.

He said, “So, Mikey, you ready to take the walk?”

Douthitt smacked his lips on his palm and blew a smooch at Harry. “I’m a nonparticipational particulator,” he grinned. “So you can kiss my white ass, nigger.”

Three seconds later Douthitt was kissing the wall as Harry applied the cuffs. I wandered off to find some disinfecting hand soap.

Chapter 40

We booked Douthitt, gave him his phone call. I convinced Harry to wait and see who showed as counsel, since Douthitt’s lawyer was special-ordered. Most of these guys used bargain-basement attorneys who had grubby offices squeezed between the bail bondsmen by the courthouse.

Instead, the guy who showed up was a slender, bespectacled guy in his thirties with a tailored pinstripe suit and a creamy leather briefcase that probably cost more than thirty of the canvas satchels I used to tote around papers. Lawyer-boy was using a gold pen to scribe his name into the visitor’s log.

“I know that guy from somewhere,” I said.

“So do I,” Harry said. “Why?”

The image formed, Mr Briefcase standing silently by as a bald bulldog barked at me through a cloud of musk.

I said, “I’m pretty sure he was with Scaler’s lawyer, Carleton, the day we first interviewed Mrs Scaler.”

“Hey,” I called across the room to the guy. “What group of shysters you practice with?”

The guy looked up, pursed his lips. Ignored me. I nodded to Harry and we walked over, stood at his side. We were both taller.

“Carleton & Associates, right?” I bayed, slapping a heavy hand over the poor guy’s skinny shoulder. “Your firm handles all the Scaler enterprises? Why’s a white-shoe hotshot like your fine self even looking at a piece of shit like Michael Douthitt?”

The lawyer flinched at my touch. He looked like he wanted to ditch the fancy briefcase and pen and sprint to the street for safety. I wondered if he’d ever been inside a jail before.

“I’m trying to make partner,” the lawyer said, eyes pleading to be left alone. “I just do what I’m told.”

We headed back to the detectives’ room. Harry was agitated but trying to hold it together. We needed full investigative mode, and that meant emotionless. Emotion crippled logic, and only logic could blaze a path to the heart of this maze. Still, Harry was having a hard time keeping his heart from eclipsing his brain.

“Carson? What if she’s…”

He couldn’t finish. The unspoken was that Noelle might well be at the bottom of Mobile Bay, or in a hole at the edge of a festering swamp.

“She’s fine, Harry. Hold on to that.”

“What did she ever do to anyone?”

“Keep it tight, bro.” I think he’d said the same thing to me a few days back. I hadn’t kept it tight at all.

Harry took a deep breath, began: “Assume the tithe envelope ties Noelle to some aspect of Scaler’s enterprises. That he or someone in the Scaler organization knew who was in the torched house. Maybe put them there. Someone who knew there was a baby out there that was, in some strange way, special.”

“And?”

“Now we’ve got a group of white supremacists who’ve kidnapped her. Possibly targeting her for death.”

“I read you,” I said. “But why didn’t the overseers giving the orders check with Douthitt before making the second, successful attempt? How did they know Noelle was still in the third incubator? Or in the PICU, for that matter? Doc Norlin said she was ready to head to the regular neonatal-care unit.”

“Another pair of eyes in the hospital?”

“Possibility,” I mulled. “But if Douthitt did the job right the first time, why not just use him?”

“That’s nuts-and-bolts stuff,” Harry growled. “We’ve got to come up with what’s underneath this vat of slime. Who’s keeping it cooking?”

“I think you’re on the righteous road, bro,” I consoled. “Every time we learn something, it’s touching the past. Did you get that Meltzer grew up in the county adjoining the county Scaler came up in? And how about Tut? He goes back thirty years with Scaler. Meltzer, Scaler, Tut…all about the same age, mid fifties. Carleton, too.”

Tom Mason knocked at the door. Tom frowned, held up a call message.

“I just got word that Dean Tutweiler’s dead.”

“What?” Harry and I said in unison.

Tom shook his head. “The Dean was found in his home about fifteen minutes ago. How about the two of you go take a look?”

Tutweiler owned an impressive multi-columned house in west Mobile, not far from the college. The house stood alone at the end of a street, an acre of yard surrounded by deciduous woods.

The uniforms who’d responded when the body was discovered by Tutweiler’s housekeeper – did everyone have a maid but me? – had the sense to realize the potential of the situation, choosing to call the death in on a personal cellphone and not over the air and thus susceptible to police-band-monitoring media types. There were no news vans, no neighbors milling on the lawn with cellphones in hand.

Clair was on the scene as the rep from the ME’s office, which showed the weight of the event. Clair only worked a scene if there was something new she might learn, or the case carried political or celebrity-style weight. Tutweiler, unfortunately, qualified as both.

Tut was sprawled in red silk boxers on a couch. His mouth was open, his tongue lolling. His eyes looked heavenward, which I found ironic. White foam had dried on his cheek. The living room boasted expensive furniture and decorations, but not a touch of personality. It was as if a door-to-door ambience salesman had sold the Dean a pre-selected grouping: the Yawn Suite.

Clair was standing by the body. She looked up from her notes. I saw a split-second struggle over whether to look concerned or nonchalant, opting for the latter.

“Hi, Carson,” she said, the blue eyes as dazzling as always. “How are you?”

“Engaged in the moment,” I said. “I’m here. What you got?”

“An OD by the looks. That’s so far. I’ll know more when we get him to the morgue. Check the pillow beside him.”

I looked down, saw a syringe and an umarked bottle of solution.

“That’s what makes you think OD? Maybe it’s medication of some sort.”

“Look here. His feet.”

I bent as Clair carefully spread the Dean’s long blue-white tootsies, the nails in need of trimming. I saw punctures between the digits. Clair said, “Standard low-profile junkie injection sites. He’s hidden them in other places as well.”

William S. Burroughs claimed being a junkie was no big deal if you had enough money to guarantee access to good dope. You were like anyone else, except you pumped a feel-good substance into your veins. Burroughs believed the deleterious effects of junk weren’t the drug’s doing, but caused by the typical junkie lifestyle of malnutrition and disease and living in a city’s danger zones.

“So our boy’s had a monkey riding him for a while?” I suggested.

“Years, maybe. His feet are riddled. Hips, too.”

“Is Tut married?” I asked, looking around. No sense of a woman’s presence, hardly a sense of a man’s.

Harry shook his head. “Everything on the web said he’s always been single. His standard line was that he was married to his service to God.”

Harry stood beside the couch, bounced up and down. I heard squishing. Harry bent and patted the carpet.

“There’s water on the floor. The carpet’s wet.”

I crouched over the carpet and sniffed. “Just like at Scaler’s scene and Chinese Red’s. I’m taking bets it’s sea water.”

No one bet against me.

I looked out the window, saw a dark-suited James Carleton stalking toward the house all by his lonesome, his deep-blue M-Benz in the drive. He stopped and talked to a group of uniforms for a few seconds, then pressed past, heading for the door.

No knock. He stepped inside like everywhere was his house. I turned, widened my eyes in false delight, clapped my hands.

“Look who’s here, Harry – Jimmy Carleton. Lookin’ good, Jimmy!” I brayed, treating the upmarket lawyer like the thirty-buck-an-hour ambulance chasers we schmoozed in the courthouse halls.

Carleton eyed us like something unpleasant into which he’d planted the soles of his five-hundred-buck Italian loafers.

“Nothing can be taken from this house without direct linkage to the scene,” he barked, cranking into payday mode, on the clock. “Any and all items taken must be entered in a –”

“How’d you know?” I said.

He scowled. I’d interrupted his cash flow. “Know what?”

“About Tutweiler’s death. No one knows but us chickens here on the scene. It hasn’t been broadcast.”

The face blanked. “I didn’t know until a minute ago,” he said. “I had some papers for Dean Tutweiler to sign. Official papers. I saw the cars, the police. I parked and ran up, heard the terrible news. It’s a horrendous shock.”

I couldn’t read his face. “Could you show me the papers?” I asked.

“Papers?”

“The ones you were going to have the Dean sign. You must have some papers in that fancy briefcase with a dotted line for the Dean to sign on, right?”

He pulled the case closer. “Anything I have in this briefcase is subject to attorney-client privilege.”

“I’m not looking for the secret recipe for Coca-Cola,” I prodded. “I’m just interested in seeing a dotted line ready for the Dean’s pen point.”

Carleton did what lawyers and politicians do when confronted by an unruly question: changed the subject, looking at his watch and shooting me a glare.

“I suppose this will be in the news within the hour, just like the sordid details of Richard’s sad death. Don’t you people have any clamps on your leaks? It’s a matter of humanity, for God’s sake.”

“Guess not,” I shrugged. “Do you know how the Dean died, Mr Carleton?”

“How would I know? I just got here. A heart attack, I’d imagine. The stress of the past week.”

Carleton retreated to the front porch as Harry and I inspected the scene. It seemed a typical OD, like Chinese Red’s. Only this one was a world away from the apartment in the Hoople, no matter how nicely the benighted Mr O’Fong, scion of the world, had appointed his small space.

“You think Carleton knew Tutweiler was dead? Harry asked when we finally signed the body over to Clair and her people.

“Interesting question,” I said.

I bid farewell to Clair, politely. As I climbed in the car I saw her shoot a glance at Harry. While yawning nonchalantly, he slipped his hand out the window and gave her some kind of signal.

Clair smiled at whatever it was.

Chapter 41

We drove past Carleton, sitting in his massive chunk of German engineering with a phone to his ear, the darkened windows tight.

“Stop,” I said to Harry.

He pulled beside Carleton’s driver’s window. I made the roll-down-your-window motion. It slid down as if tracking on wet butter.

“What?” he demanded.

“How old are you, Mr Carleton?”

“Fifty-four,” he said. “Why?”

“Just taking a survey. I’m thirty-six, Harry’s forty-something.” I decided to drop a bomb, see what it took down. “How old do you think Arnold Meltzer is?”

His eyes reacted, but not his face. A good lawyer can do that.

“We know you know him,” I said, expecting another blank-faced Who? or What are you talking about?

“So the fuck what?” he said.

I nodded toward the house.

“First Scaler, now Tutweiler. What’s Meltzer’s connection?”

“I don’t have the slightest idea what you’re talking about. Reverend Scaler, the poor sick man, died of a heart attack. It appears that Dean Tutweiler killed himself. The pretty lady in there said as much.”

“No,” I said. “The pretty lady in there is my girlfriend. And the pretty lady is a professional. She’d never leap to such a conclusion. I think that’s what you’re planning on – suicide. Where did you get your forensic training, Mr Carleton?”

“I’ll thank you to remove yourself from my presence before I talk to your Chief.”

“How do you know Arnold Meltzer?”

“Anything I might say about Arnold Meltzer is under privilege. Now, if you’ll excuse me.” The window started to roll up.

“Privilege?” I said. “So Meltzer’s your client.”

“Everyone is entitled to representation under the law,” he said, his voice like oil over an eel. “You might try reading the Constitution, Detective. It actually affects parts of law enforcement.”

The window closed. I heard Harry’s door open. The blue Mercedes moved ahead a yard, stopped dead.

Harry was standing in front of its grille. The window dropped.

“Get out of my way,” Carleton barked. “This is harassment.”

Harry put his foot on the bumper. Leaned toward the window. “Not harassment,” he said, his voice as cold as wind from hell. “A warning. If anything happens to that little girl, I’ll cut everyone involved down like a scythe.”

“I h-have absolutely no idea what you’re t-talking about,” Carleton sputtered, putting the car in reverse and backing away.

We drove off feeling that somehow we were shaking things loose. We didn’t know what, but experience had taught us that when high-priced mouthpieces look scared, we were doing something right.

“What next, Sherlock?” Harry said. He hadn’t called me that in weeks.

“Aim for the Hoople Hotel,” I said. “I got a hunch and that starts with H.”

The room clerk, Jaime Critizia, shot a frightened look when we entered the Hoople.

“Stay seated, Jaime,” Harry said. “It’s like before, just a conversation. No La Migre if you level with us.”

Critizia relaxed, nodded his understanding.

“Chinese Red, your dead boarder?” I made a syringe-plunge motion with my fingers above my forearm. “I need to know if he ever had friends over here.”

“He had some friends that were…not friends. They came because Mr Red was handsome.”

“They came for sex?”

Critizia wrinkled his nose as if smelling something even worse than the lobby of his workplace. “Ees a bad job here, but I have a sick back and cannot work the chickens or fields or gardens. I must have money for my family in Ecuador, and I can sit in this job. The pay ees no so good as the chickens factory or fields, but I can work long hours to make up.”

Critizia was telling us he only worked at the Hoople because he had no other choice. I figured he’d been a good, upstanding Catholic back in rural wherever, had seen more vice in his first day at the desk of the Hoople than he’d seen in his life. And he wasn’t part of those goings-on.

“Si. For the sex.”

“One of the people who might have come for the sex,” I said. “Did he look at all like this…?”

I held out a photo of Tutweiler pulled from the net. Critizia took a long look before he nodded.

“He dressed to look different. A light hair thing.” Critizia wiggled his fingers over his head, meaning a wig. “And always sunglasses, even when it rains.”

“He was here how many times?”

“One time every week, usually Wednesday in the night. Sometimes he would be here on Sunday.”

“A new meaning for Sunday services,” I said.

Heading outside, we saw Shanelle emerging from a minimart across the street, eating a sloppy po’boy from wax paper. Her green dress had required less cloth than my handkerchief. The gold clogs had turned to sparkly red pumps like she was ready to tap dance over the rainbow.

She saw us and ran over.

“Harry, you look sweet as honey today. How ’bout you and me get tickets for Rio and fly away some night and –”

Harry held up his hand.

“Gotta talk serious here, Shanelle. How well did you know Chinese Red?”

“We was friends, Harry. We’d go to the docks and talk. It’s so unfair he’s gone.”

“Tell me about his last days.”

“Red got clean, Harry. He kicked. He was getting better.”

“But still selling himself, right?”

“When he had to, and only to a couple of high-price clients. He was putting the money away and not in his veins. He was gonna start his own detail shop next year.”

“You’re sure, Shanelle?”

“I ain’t ever been sure of much, Harry. But that’s one of the few things I know for fact.”

Score one for Ryan’s optimism, I thought as we drove away.

“Tut was a regular customer of Chinese Red,” Harry said, rolling up the window. “If someone who knew of the unholy alliance between Dean Tutweiler and Red suddenly needed a way to destroy Scaler’s reputation, putting Scaler with a gay black man with a history of prostitution…”

“Was the kind of inspired move I’d expect of a guy like Arnold Meltzer,” I finished. “But Meltzer lacks the balls to slice pepperoni. He delegates. Which probably means we need to know more about Deputy Baker,” I said, pulling my phone.

I made my call to Ben Belker as Harry drove. Ben was out having lunch and I told Wanda Tenahoe we needed everything Ben had on Boots Baker. She knew who I was talking about, judging by the Ugh when I mentioned Baker’s name. Ben would call back soon, she promised.

With nothing else to do, Harry and I picked up po’boys and headed for the causeway. He didn’t want to eat, but I shoved the sandwich into his hands, let instinct take over.

We leaned against the car and ate without a word, watching the boats and herons and pelicans.

“Has it ever gotten to you, Harry?” I said. “I mean, before today?”

My cell interrupted. It was Ben Belker. He said, “Can rattlesnakes catch hydrophobia, Carson?”

“Why?”

“That’s how I describe Delbert aka ‘Boots’ Baker. He got the nickname from kicking people’s faces to a pulp. While others held them, of course. He’s a rattlesnake with rabies.”

“You know he’s a county sheriff’s deputy?”

“I’ll add that to his file. He must have gotten fired from his last job, guarding at a Mississippi prison. Maybe they found out about his previous prison work.”

“You lost me, Ben.”

“Baker was a guard at Abu Ghraib. One of the worst of a bad lot, a sadist. You heard about water-boarding? Baker invented watersheeting.”

“Watersheeting?”

“Not a bad idea, as first conceived. Soak a sheet or blanket in water, wrap it around someone you want to move – a mummy wrap. Ever try and wriggle from wet fabric, Carson?”

I thought of how hard it was to pull off a wet sweatshirt.

“I can imagine it.”

“Except Baker wrapped prisoners and did things like add a bit of electricity to the mix. They got pain, he got pleasure, and no proof was ever left on the bodies.”

I pictured Baker’s system in my mind. “Because the wet blankets acted as a soft restraint. The prisoners didn’t flail around and contuse themselves.”

“Yep. Just laid there like screaming burritos.”

I shook my head. Saw Harry slipping on water at Scaler’s death scene. The wet floor at Chinese Red’s apartment. Glenn Watkins delivering the verdict of sea water and petrochemicals, like water found near boat traffic.

“You know where Baker lives, Ben?”

“Address is 432 Grayson Court. It’s along the Intercoastal Waterway.”

The waterway was a canal running through the southern half of Mobile county, heavily used by commercial traffic: barges, tows, shrimp boats. The water was often shiny with oil.

“Thanks, Ben.”

I hung up. Looked at Harry. Told him we were heading south.

Delbert “Boots” Baker lived in a ranch-style house on a short spur of the Intercoastal Waterway. It would have been a nice-looking place except for being entirely surrounded by hurricane fencing, the fence dotted with Keep Out and No Trespassing signs. I saw two security cameras pointing toward the street, knew there would be more. I looked for signs of attack dogs, but realized people with paranoiac, possibly psychotic personalities didn’t tend toward keeping animals. They were so inwardly focused that animals distracted them from themselves.

“Looks like Deputy Baker’s built himself a fortress on the water,” Harry said.

“A paranoid,” I said. “Worse, a paranoiac wrecking ball.”

We got out and walked the fence line. The adjoining property was a scrap yard, beater cars hauled or driven in on their last legs to be sold for scrap, hulking piles of metal stacked close to the channel and awaiting passage to China or wherever was using our cast-offs these days.

The house seemed empty of life, no curtains parting. I figured Baker was on duty somewhere, like the day he’d had the confrontation with Al Bustamente. The thought almost amused me until it led to two others: Had Baker been the one to attack Al Bustamente last week? It made sudden and perfect sense: a sociopath of Baker’s ilk would have felt the burn of Bustamente’s derisive words long after the confrontation. I figured Bustamente was lucky he’d only been injured and not killed.

And had Baker been standing in the prints, not because he was ignorant, but because he was trying to destroy evidence? That he knew – or had been part of – whatever had gone down at the house in the middle of nowhere?

I filed these thoughts away, stepping over pieces of metal and car parts that had drifted over from the junkyard, half hiding in the kudzu and poison ivy.

“Look at the back of the house,” I said, pointing.

We saw a pier on the water, a sleek, thirty-foot cruiser berthed against the pilings, a boat that could cross the Gulf like I stepped over a creek. I looked to a concrete pad behind the house, saw two battered five-gallon containers, the big blue plastic jobs, short lengths of rope on the handles. I had a similar container I filled with drinking water when camping in the Smoky Mountains.

“What are you thinking, Carson?”

“I’m thinking a short walk takes Baker to his pier, filling his jugs by setting them in the water.”

The rest of the scenario unfolded: Baker, with the help of one or two of his crew, soaking a blanket from the containers, wrapping Richard Scaler when he answered the knock at his door, immobilizing him for a nighttime run to the camp. Or perhaps Scaler had been lured to the camp, immobilized there. Water had pooled beneath Scaler, suggesting they’d hung him up – struggling, but making none of the marks of struggle to alert the coroner.

“Tutweiler and Chinese Red were immobilized for heroin overdoses,” Harry said. “But what happened to Scaler? Potassium chloride? An air bubble?”

Inject either of the two into the blood and bang, heart-attack city. There was virtually no way to discern that the death was anything but a cardiac event.

“Fits,” I said. “Or maybe Scaler had a heart attack from sheer terror, saving Baker a step. They whipped his back before he died, but once Scaler was in the air, he was helpless. Tie the gag in his mouth, ram the plug into his anus. Set out some candles for effect. There was nothing to be done about the water dripping off the blanket, but they probably figured it would evaporate before the body was found – a miscalculation inside a cool house.”

“Where do you think Baker is?” Harry asked, looking at his watch. “It’s late for him to still be at work.”

“He could be working a swing-shift. Or maybe he’s out torturing small animals, the kind of hobby he’d have, I expect.”

“This place makes my skin crawl,” Harry said. “Let’s bag it for now. But make a note to come back real soon.”

We pulled away, both shooting glances in the rear-views at Baker’s waterfront fortress.

“What’s the strangest thing about this case, Carson?” Harry asked when we were back on the main highway, simultaneously veering so close to a passing gasoline truck I could have leaned out and refilled our tank.

I thought for several minutes, tumbling pictures and events through my mind.

“Why the hatchet job on Scaler’s reputation?” I said. “If someone wanted Scaler out of the way, why not just have him popped with a contract hit?”

“Then he’d just be dead,” Harry noted. “Now he’s dead and discredited. The big question is…”

“Why discredited?” I said, looking out into the night sky. “It’s always ‘Why?’”

We got to the department’s parking garage. It was quiet, the night-patrol shift out on the streets, the detectives long home.

“You going home?” Harry asked.