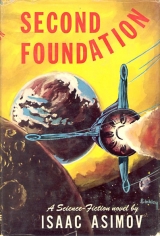

Текст книги "Second Foundation"

Автор книги: Isaac Asimov

Соавторы: Isaac Asimov

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 8 (всего у книги 14 страниц)

"Well?"

"Well, why is that so? At times like these, nothing happens without a reason. What if it is not superstition only that makes the Mule's palace inviolate? What if the Second Foundation has so arranged matters? In short what if the results of the Mule's five-year search are within-"

"Oh, p… poppycock."

"Why not?" demanded Anthor. "Throughout its history the Second Foundation has hidden itself and interfered in Galactic affairs in minimal fashion only. I know that to us it would seem more logical to destroy the Palace or, at the least, to remove the data. But you must consider the psychology of these master psychologists. They are Seldons; they are Mules and they work by indirection, through the mind. They would never destroy or remove when they could achieve their ends by creating a state of mind. Eh?"

No immediate answer, and Anthor continued, "And you, Munn, are just the one to get the information we need."

"I?"*** It was an astounded yell. Munn looked from one to the other rapidly, "I can't do such a thing. I'm no man of action; no hero of any teleview. I'm a librarian. If I can help you that way, all right, and I'll risk the Second Foundation, but I'm not going out into space on any qu… quixotic thing like that."

"Now, look," said Anthor, patiently, "Dr. Darell and I have both agreed that you're the man. It's the only way to do it naturally. You say you're a librarian. Fine! What is your main field of interest? Muliana! You already have the greatest collection of material on the Mule in the Galaxy. It is natural for you to want more; more natural for you than for anyone else. You could request entrance to the Kalgan Palace without arousing suspicion of ulterior motives. You might be refused but you would not be suspected. What's more, you have a one-man cruiser. You're known to have visited foreign planets during your annual vacation. You've even been on Kalgan before. Don't you understand that you need only act as you always have?"

"But I can't just say, 'W… won't you kindly let me in to your most sacred shrine, M… Mr. First Citizen?’ "

"Why not?"

"Because, by the Galaxy, he won't let me!"

"All right, then. So he won't Then you'll come home and we’ll think of something else."

Munn looked about in helpless rebellion. He felt himself being talked into something he hated. No one offered to help him extricate himself.

So in the end two decisions were made in Dr. Darell's house. The first was a reluctant one of agreement on the part of Munn to take off into space as soon as his summer vacation began.

The other was a highly unauthorized decision on the part of a thoroughly unofficial member of the gathering, made as she clicked off a sound-receiver and composed herself for a belated sleep. This second decision does not concern us just yet.

10. Approaching Crisis

A week had passed on the Second Foundation, and the First Speaker was smiling once again upon the Student.

"You must have brought me interesting results, or you would not be so filled with anger."

The Student put his hand upon the sheaf of calculating paper he had brought with him and said, "Are you sure that the problem is a factual one?"

"The premises are true. I have distorted nothing."

"Then I must accept the results, and I do not want to."

"Naturally. But what have your wants to do with it? Well, tell me what disturbs you so. No, no, put your derivations to one side. I will subject them to analysis afterward. Meanwhile, talk to me. Let me judge your understanding."

"Well, then, Speaker – It becomes very apparent that a gross overall change in the basic psychology of the First Foundation has taken place. As long as they knew of the existence of a Seldon Plan, without knowing any of the details thereof, they were confident but uncertain. They knew they would succeed, but they didn't know when or how. There was, therefore, a continuous atmosphere of tension and strain – which was what Seldon desired. The First Foundation, in other words, could be counted upon to work at maximum potential."

"A doubtful metaphor," said the First Speaker, "but I understand you."

"But now, Speaker, they know of the existence of a Second Foundation in what amounts to detail, rather merely than as an ancient and vague statement of Seldon's. They have an inkling as to its function as the guardian of the Plan. They know that an agency exists which watches their every step and will not let them fall. So they abandon their purposeful stride and allow themselves to be carried upon a litter. Another metaphor, I'm afraid."

"Nevertheless, go on."

"And that very abandonment of effort; that growing inertia; that lapse into softness and into a decadent and hedonistic culture, means the ruin of the Plan. They must be self-propelled."

"Is that all?"

"No, there is more. The majority reaction is as described. But a great probability exists for a minority reaction. Knowledge of our guardianship and our control will rouse among a few, not complacence, but hostility. This follows from Korillov's Theorem-"

"Yes, yes. I know the theorem."

"I'm sorry, Speaker. It is difficult to avoid mathematics. In any case, the effect is that not only is the Foundation's effort diluted, but part of it is turned against us, actively against us."

"And is that all?"

"There remains one other factor of which the probability is moderately low-"

"Very good. What is that?"

"While the energies of the First Foundation were directed only to Empire; while their only enemies were huge and outmoded hulks that remained from the shambles of the past, they were obviously concerned only with the physical sciences. With us forming a new, large part of their environment, a change in view may well be imposed on them. They may try to become psychologists-"

"That change," said the First Speaker, coolly, "has already taken place."

The Student's lips compressed themselves into a pale line. "Then all is over. It is the basic incompatibility with the Plan. Speaker, would I have known of this if I had lived – outside?"

The First Speaker spoke seriously, "You feel humiliated, my young man, because, thinking you understood so much so well, you suddenly find that many very apparent things were unknown to you. Thinking you were one of the Lords of the Galaxy; you suddenly find that you stand near to destruction. Naturally, you will resent the ivory tower in which you lived; the seclusion in which you were educated; the theories on which you were reared.

"I once had that feeling. It is normal. Yet it was necessary that in your formative years you have no direct contact with the Galaxy, that you remain here, where all knowledge is filtered to you, and your mind carefully sharpened. We could have shown you this… this part-failure of the Plan earlier and spared you the shock now, but you would not have understood the significance properly, as you now will. Then you find no solution at all to the problem?"

The Student shook his head and said hopelessly, "None!"

"Well, it is not surprising. Listen to me, young man. A course of action exists and has been followed for over a decade. It is not a usual course, but one that we have been forced into against our will. It involves low probabilities, dangerous assumptions – We have even been forced to deal with individual reactions at times, because that was the only possible way, and you know that Psychostatistics by its very nature has no meaning when applied to less than planetary numbers."

"Are we succeeding?" gasped the Student.

"There's no way of telling yet. We have kept the situation stable so far – but for the first time in the history of the Plan, it is possible for the unexpected actions of a single individual to destroy it. We have adjusted a minimum number of outsiders to a needful state of mind; we have our agents – but their paths are planned. They dare not improvise. That should be obvious to you. And I will not conceal the worst – if we are discovered, here, on this world, it will not only be the Plan that is destroyed, but ourselves, our physical selves. So you see, our solution is not very good."

"But the little you have described does not sound like a solution at all, but like a desperate guess."

"No. Let us say, an intelligent guess."

"When is the crisis, Speaker? When will we know whether we have succeeded or not?"

"Well within the year, no doubt."

The Student considered that, then nodded his head. He shook hands with the Speaker. "Well, it's good to know."

He turned on his heel and left.

The first Speaker looked out silently as the window gained transparency. Past the giant structures to the quite, crowding stars.

A year would pass quickly. Would any of them, any of Seldon's heritage, be alive at its end?

11. Stowaway

It was a little over a month before the summer could be said to have started. Started, that is, to the extent that Homir Munn had written his final financial report of the fiscal year, seen to it that the substitute librarian supplied by the Government was sufficiently aware of the subtleties of the post – last year's man had been quite unsatisfactory – and arranged to have his little cruiser the Unimara – named after a tender and mysterious episode of twenty years past – taken out of its winter cobwebbery.

He left Terminus in a sullen distemper. No one was at the port to see him off. That would not have been natural since no one ever had in the past. He knew very well that it was important to have this trip in no way different from any he had made in the past, yet he felt drenched in a vague resentment. He, Homir Munn, was risking his neck in derring-doery of the most outrageous sort, and yet he left alone.

At least, so he thought.

And it was because he thought wrongly, that the following day was one of confusion, both on the Unimara and in Dr. Darell's suburban home.

It hit Dr. Darell's home first, in point of time, through the medium of Poli, the maid, whose month's vacation was now quite a thing of the past. She flew down the stairs in a flurry and stutter.

The good doctor met her and she tried vainly to put emotion into words but ended by thrusting a sheet of paper and a cubical object at him.

He took them unwillingly and said: "What's wrong, Poli?"

"She's gone, doctor."

"Who's gone?"

"Arcadia!"

"What do you mean, gone? Gone where? What are you talking about?"

And she stamped her foot: 'I don't know. She's gone, and there's a suitcase and some clothes gone with her and there's that letter. Why don't you read it, instead of just standing there? Oh, you men!"

Dr. Darell shrugged and opened the envelope. The letter was not long, and except for the angular signature, "Arkady," was in the ornate and flowing handwriting of Arcadia's transcriber.

Dear Father:

It would have been simply too heartbreaking to say good-by to you in person. I might have cried like a little girl and you would have been ashamed of me. So I'm writing a letter instead to tell you how much I'II miss you, even while I'm having this perfectly wonderful summer vacation with Uncle Homir. I'II take good care of myself and it won't be long before I’m home again. Meanwhile, I'm leaving you something that's all my own. You can have it now.

Your loving daughter,

Arkady.

He read it through several times with an expression that grew blanker each time. He said stiffly, "Have you read this, Poli?"

Poli was instantly on the defensive. "I certainly can't be blamed for that, doctor. The envelope has 'Poli' written on the outside, and I had no way of telling there was a letter for you on the inside. I'm no snoop, doctor, and in the years I've been with-"

Darell held up a placating hand, "Very well, Poli. It's not important. I just wanted to make sure you understood what had happened."

He was considering rapidly. It was no use telling her to forget the matter. With regard to the enemy, "forget" was a meaningless word; and the advice, insofar as it made the matter more important, would have had an opposite effect.

He said instead, "She's a queer little girl, you know. Very romantic. Ever since we arranged to have her go off on a space trip this summer, she's been quite excited."

"And just why has no one told me about this space trip?"

"It was arranged while you were away, and we forgot It's nothing more complicated than that."

Poli's original emotions now concentrated themselves into a single, overwhelming indignation, "Simple, is it? The poor chick has gone off with one suitcase, without a decent stitch of clothes to her, and alone at that. How long will she be away?"

"Now I won't have you worrying about it, Poli. There will be plenty of clothes for her on the ship. It's been all arranged. Will you tell Mr. Anthor, that I want to see him? Oh, and first – is this the object that Arcadia has left for me?" He turned it over in his hand.

Poli tossed her head. "I'm sure I don't know. The letter was on top of it and that's every bit I can tell you. Forget to tell me, indeed. If her mother were alive-"

Darell, waved her away. "Please call Mr. Anthor."

***

Anthor's viewpoint on the matter differed radically from that of Arcadia's father. He punctuated his initial remarks with clenched fists and tom hair, and from there, passed on to bitterness.

"Great Space, what are you waiting for? What are we both waiting for? Get the spaceport on the viewer and have them contact the Unimara."

"Softly, Pelleas, she's my daughter."

"But it's not your Galaxy."

"Now, wait. She's an intelligent girl, Pelleas, and she's thought this thing out carefully. We had better follow her thoughts while this thing is fresh. Do you know what this thing is?"

"No. Why should it matter what it is?'

"Because it's a sound-receiver."

"That thing?"

"It's homemade, but it will work. I've tested it. Don't you see? It's her way of telling us that she's been a party to our conversations of policy. She knows where Homir Munn is going and why. She's decided it would be exciting to go along."

"Oh, Great Space," groaned the younger man. "Another mind for the Second Foundation to pick."

"Except that there's no reason why the Second Foundation should, a priori, suspect a fourteen-year-old girl of being a danger – unless we do anything to attract attention to her, such as calling back a ship out of space for no reason other than to take her off. Do you forget with whom we're dealing? How narrow the margin is that separates us from discovery? How helpless we are thereafter?"

"But we can't have everything depend on an insane child."

She's not insane, and we have no choice. She need not have written the letter, but she did it to keep us from going to the police after a lost child. Her letter suggests that we convert the entire matter into a friendly offer on the part of Munn to take an old friend's daughter off for a short vacation. And why not? He's been my friend for nearly twenty years. He's known her since she was three, when I brought her back from Trantor. It's a perfectIy natural thing, and, in fact, ought to decrease suspicion. A spy does not carry a fourteen-year-old niece about with him."

"So. And what will Munn do when he finds her?"

Dr. Darell heaved his eyebrows once. "I can't say – but I presume she’ll handle him."

But the house was somehow very lonely at night and Dr. Darell found that the fate of the Galaxy made remarkably little difference while his daughter's mad little life was in danger.

The excitement on the Unimara, if involving fewer people, was considerably more intense.

***

In the luggage compartment, Arcadia found herself, in the first place, aided by experience, and in the second, hampered by the reverse.

Thus, she met the initial acceleration with equanimity and the more subtle nausea that accompanied the inside-outness of the first jump through hyperspace with stoicism. Both had been experienced on space hops before, and she was tensed for them. She knew also that luggage compartments were included in the ship's ventilation-system and that they could even be bathed in wall-light. This last, however, she excluded as being too unconscionably unromantic. She remained in the dark, as a conspirator should, breathing very softly, and listening to the little miscellany of noises that surrounded Homir Munn.

They were undistinguished noises, the kind made by a man alone. The shuffling of shoes, the rustle of fabric against metal, the soughing of an upholstered chair seat retreating under weight, the sharp click of a control unit, or the soft slap of a palm over a photoelectric cell.

Yet, eventually, it was the lack of experience that caught up with Arcadia. In the book films and on the videos, the stowaway seemed to have such an infinite capacity for obscurity. Of course, there was always the danger of dislodging something which would fall with a crash, or of sneezing – in videos you were almost sure to sneeze; it was an accepted matter. She knew all this, and was careful. There was also the realization that thirst and hunger might be encountered. For this, she was prepared with ration cans out of the pantry. But yet things remained that the films never mentioned, and it dawned upon Arcadia with a shock that, despite the best intentions in the world, she could stay hidden in the closet for only a limited time.

And on a one-man sports-cruiser, such as the Unimara, living space consisted, essentially, of a single room, so that there wasn't even the risky possibility of sneaking out of the compartment while Munn was engaged elsewhere.

She waited frantically for the sounds of sleep to arise. If only she knew whether he snored. At least she knew where the bunk was and she could recognize the rolling protest of one when she heard it. There was a long breath and then a yawn. She waited through a gathering silence, punctuated by the bunk's soft protest against a changed position or a shifted leg.

The door of the luggage compartment opened easily at the pressure of her finger, and her craning neck-

There was a definite human sound that broke off sharply.

Arcadia solidified. Silence! Still silence!

She tried to poke her eyes outside the door without moving her head and failed. The head followed the eyes.

Homir Munn was awake, of course – reading in bed, bathed in the soft, unspreading bed light, staring into the darkness with wide eyes, and groping one hand stealthily under the pillow.

Arcadia's head moved sharply back of itself. Then, the light went out entirely and Munn's voice said with shaky sharpness, "I've got a blaster, and I'm shooting, by the Galaxy-"

And Arcadia wailed, "It's only me. Don't shoot."

Remarkable what a fragile flower romance is. A gun with a nervous operator behind it can spoil the whole thing.

The light was back on – all over the ship – and Munn was sitting up in bed. The somewhat grizzled hair on his thin chest and the sparse one-day growth on his chin lent him an entirely fallacious appearance of disreputability.

Arcadia stepped out, yanking at her metallene jacket which was supposed to be guaranteed wrinkleproof.

After a wild moment in which he almost jumped out of bed, but remembered, and instead yanked the sheet up to his shoulders, Munn gargled, "W… wha… what-"

He was completely incomprehensible.

Arcadia said meekly, "Would you excuse me for a minute? I've got to wash my hands." She knew the geography of the vessel, and slipped away quickly. When she returned, with her courage oozing back, Homir Munn was standing before her with a faded bathrobe on the outside and a brilliant fury on the inside.

"What the black holes of Space are you d… doing aboard this ship? H… how did you get on here? What do you th… think I'm supposed to do with you? What's going on here?"

He might have asked questions indefinitely, but Arcadia interrupted sweetly, "I just wanted to come along, Uncle Homir."

"Why? I'm not going anywhere?"

"You're going to Kalgan for information about the Second Foundation."

And Munn let out a wild howl and collapsed completely. For one horrified moment, Arcadia thought he would have hysterics or beat his head against the wall. He was still holding the blaster and her stomach grew ice-cold as she watched it.

"Watch out – Take it easy -" was all she could think of to say.

But he struggled back to relative normality and threw the blaster on to the bunk with a force that should have set it off and blown a hole through the ship's hull.

"How did you get on?" he asked slowly, as though gripping each word with his teeth very carefully to prevent it from trembling before letting it out.

"It was easy. I just came into the hangar with my suitcase, and said, 'Mr. Munn's baggage!' and the man in charge just waved his thumb without even looking up."

"I'll have to take you back, you know," said Homir, and there was a sudden wild glee within him at the thought. By Space, this wasn't his fault.

"You can't," said Arcadia, calmly, "it would attract attention."

"What?"

"You know. The whole purpose of your going to Kalgan was because it was natural for you to go and ask for permission to look into the Mule's records. And you've got to be so natural that you're to attract no attention at all. If you go back with a girl stowaway, it might even get into the tele-news reports."

"Where did you g… get those notions about Kalgan? These… uh… childish-" He was far too flippant for conviction, of course, even to one who knew less than did Arcadia.

"I heard," she couldn't avoid pride completely, "with a sound-recorder. I know all about it – so you've got to let me come along."

"What about your father?" He played a quick trump. "For all he knows, you're kidnapped… dead."

"I left a note," she said, overtrumping, "and he probably knows he mustn't make a fuss, or anything. You'll probably get a space-gram from him."

To Munn the only explanation was sorcery, because the receiving signal sounded wildly two seconds after she finished.

She said: "That's my father, I bet," and it was.

The message wasn't long and it was addressed to Arcadia. It said: "Thank you for your lovely present, which I'm sure you put to good use. Have a good time."

"You see," she said, "that's instructions."

Homir grew used to her. After a while, he was glad she was there. Eventually, he wondered how he would have made it without her. She prattIed! She was excited! Most of all, she was completely unconcerned. She knew the Second Foundation was the enemy, yet it didn't bother her. She knew that on Kalgan, he was to deal with a hostile officialdom, but she could hardly wait.

Maybe it came of being fourteen.

At any rate, the week-long trip now meant conversation rather than introspection. To be sure, it wasn't a very enlightening conversation, since it concerned, almost entirely, the girl's notions on the subject of how best to treat the Lord of Kalgan. Amusing and nonsensical, and yet delivered with weighty deliberation.

Homir found himself actually capable of smiling as he listened and wondered out of just which gem of historical fiction she got her twisted notion of the great universe.

It was the evening before the last jump. Kalgan was a bright star in the scarcely-twinkling emptiness of the outer reaches of the Galaxy. The ship's telescope made it a sparkling blob of barely-perceptible diameter.

Arcadia sat cross-legged in the good chair. She was wearing a pair of slacks and a none-too-roomy shirt that belonged to Homir. Her own more feminine wardrobe had been washed and ironed for the landing.

She said, "I'm going to write historical novels, you know." She was quite happy about the trip. Uncle Homir didn't the least mind listening to her and it made conversation so much more pleasant when you could talk to a really intelligent person who was serious about what you said.

She continued: "I've read books and books about all the great men of Foundation history. You know, like Seldon, Hardin, Mallow, Devers and all the rest. I've even read most of what you've written about the Mule, except that it isn't much fun to read those parts where the Foundation loses. Wouldn't you rather read a history where they skipped the silly, tragic parts?"

"Yes, I would," Munn assured her, gravely. "But it wouldn't be a fair history, would it, Arkady? You'd never get academic respect, unless you give the whole story."

"Oh, poof. Who cares about academic respect?" She found him delightful. He hadn't missed calling her Arkady for days. "My novels are going to be interesting and are going to sell and be famous. What's the use of writing books unless you sell them and become well-known? I don't want just some old professors to know me. It's got to be everybody."

Her eyes darkened with pleasure at the thought and she wriggled into a more comfortable position. "In fact, as soon as I can get father to let me, I'm going to visit Trantor, so's I can get background material on the First Empire, you know. I was born on Trantor; did you know that?"

He did, but he said, "You were?" and put just the right amount of amazement into his voice. He was rewarded with something between a beam and a simper.

"Uh-huh. My grandmother… you know, Bayta Darell, you've heard of her… was on Trantor once with my grandfather. In fact, that's where they stopped the Mule, when all the Galaxy was at his feet; and my father and mother went there also when they were first married. I was born there. I even lived there till mother died, only I was just three then, and I don't remember much about it. Were you ever on Trantor, Uncle Homir?"

"No, can't say I was." He leaned back against the cold bulkhead and listened idly. Kalgan was very close, and he felt his uneasiness flooding back.

"Isn't it just the most romantic world? My father says that under Stannel V, it had more people than any ten worlds nowadays. He says it was just one big world of metals – one big city – that was the capital of all the Galaxy. He's shown me pictures that he took on Trantor. It's all in ruins now, but it's still stupendous. I'd just love to see it again. In fact… Homir!"

"Yes?"

"Why don't we go there, when we're finished with Kalgan?"

Some of the fright hurtled back into his face. "What? Now don't start on that. This is business, not pleasure. Remember that."

"But it is business" she squeaked. "There might be incredible amounts of information on Trantor, don't you think so?"

"No, I don't."*** He scrambled to his feet "Now untangle yourself from the computer. We've got to make the last jump, and then you turn in." One good thing about landing, anyway; he was about fed up with trying to sleep on an overcoat on the metal floor.

The calculations were not difficult. The "Space Route Handbook" was quite explicit on the Foundation-Kalgan route. There was the momentary twitch of the timeless passage through hyperspace and the final light-year dropped away.

The sun of Kalgan was a sun now – large, bright, and yellow-white; invisible behind the portholes that had automatically closed on the sun-lit side.

Kalgan was only a night's sleep away.

12. Lord

Of all the worlds of the Galaxy, Kalgan undoubtedly had the most unique history. That of the planet Terminus, for instance, was that of an almost uninterrupted rise. That of Trantor, once capital of the Galaxy, was that of an almost uninterrupted fall. But Kalgan-

Kalgan first gained fame as the pleasure world of the Galaxy two centuries before the birth of Hari Seldon. It was a pleasure world in the sense that it made an industry – and an immensely profitable one, at that – out of amusement.

And it was a stable industry. It was the most stable industry in the Galaxy. When all the Galaxy perished as a civilization, little by little, scarcely a feather's weight of catastrophe fell upon Kalgan. No matter how the economy and sociology of the neighboring sectors of the Galaxy changed, there was always an elite; and it is always the characteristic of an elite that it possesses leisure as the great reward of its elite-hood.

Kalgan was at the service, therefore, successively – and successfully – of the effete and perfumed dandies of the Imperial Court with their sparkling and libidinous ladies; of the rough and raucous warlords who ruled in iron the worlds they had gained in blood, with their unbridled and lascivious wenches; of the plump and luxurious businessmen of the Foundation, with their lush and flagitious mistresses.

It was quite undiscriminating, since they all had money. And since Kalgan serviced all and barred none; since its commodity was in unfailing demand; since it had the wisdom to interfere in no world's politics, to stand on no one's legitimacy, it prospered when nothing else did, and remained fat when all grew thin.

That is, until the Mule. Then, somehow, it fell, too, before a conqueror who was impervious to amusement, or to anything but conquest. To him all planets were alike, even Kalgan.

So for a decade, Kalgan found itself in the strange role of Galactic metropolis; mistress of the greatest Empire since the end of the Galactic Empire itself.

And then, with the death of the Mule, as sudden as the zoom, came the drop. The Foundation broke away. With it and after it, much of the rest of the Mule's dominions. Fifty years later there was left only the bewildering memory of that short space of power, like an opium dream. Kalgan never quite recovered. It could never return to the unconcerned pleasure world it had been, for the spell of power never quite releases its bold. It lived instead under a succession of men whom the Foundation called the Lords of Kalgan, but who styled themselves First Citizen of the Galaxy, in imitation of the Mule's only title, and who maintained the fiction that they were conquerors too.

The current Lord of Kalgan had held that position for five months. He had gained it originally by virtue of his position at the head of the Kalganian navy, and through a lamentable lack of caution on the part of the previous lord. Yet no one on Kalgan was quite stupid enough to go into the question of legitimacy too long or too closely. These things happened, and are best accepted.

Yet that sort of survival of the fittest in addition to putting a premium on bloodiness and evil, occasionally allowed capability to come to the fore as well. Lord Stettin was competent enough and not easy to manage.