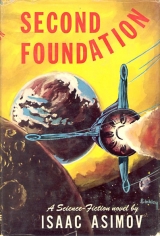

Текст книги "Second Foundation"

Автор книги: Isaac Asimov

Соавторы: Isaac Asimov

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 6 (всего у книги 14 страниц)

(She had written "intricacies" here also, but decided not to risk it a second time.)

complications. All our planets still revere their memories although centuries have passed.

"Eventually, the Foundation established a commercial system which controlled a large portion of the Siwennian and Anacreonian sectors of the Galaxy, and even defeated the remnants of the old Empire under its last great general, Bel Riose. It seemed that nothing could now stop the workings of Seldon's plan. Every crisis that Seldon had planned had come at its appropriate time and had been solved, and with each solution the Foundation had taken another giant stride toward Second Empire and peace.

"And then,

(Her breath came short at this point, and she hissed the word, between her teeth, but the Transmitter simply wrote them calmly and gracefully.)

with the last remnants of the dead First Empire gone and with only ineffectual warlords ruling over the splinters and remnants of the decayed colossus,

(She got that phrase out of a thriller on the video last week, but old Miss Erlking never listened to anything but symphonies and lectures, so she'd never know.)

there came the Mule.

"This strange man was not allowed for in the Plan. He was a mutant, whose birth could not have been predicted. He had strange and mysterious power of controlling and manipulating human emotions and in this manner could bend all men to his will. With breath-taking swiftness, he became a conqueror and Empire-builder, until, finally, he even defeated the Foundation itself.

"Yet he never obtained universal dominion, since in his first overpowering lunge he was stopped by the wisdom and daring of a great woman

(Now there was that old problem again. Father would insist that she never bring up the fact that she was the grandchild of Bayta Darell. Everyone knew it and Bayta was just about the greatest woman there ever was and she had stopped the Mule singlehanded.)

in a manner the true story of which is known in its entirety to very few.

(There! If she had to read it to the class, that last could he said in a dark voice, and someone would be sure to ask what the true story was, and then – well, and then she couldn't help tell the truth if they asked her, could she? In her mind, she was already wordlessly whizzing through a hurt and eloquent explanation to a stern and questioning paternal parent.)

"After five years of restricted rule, another change took place, the reasons for which are not known, and the Mule abandoned all plans for further conquest. His last five years were those of an enlightened despot.

"It is said by some that the change in the Mule was brought about by the intervention of the Second Foundation. However, no man has ever discovered the exact location of this other Foundation, nor knows its exact function, so that theory remains unproven.

"A whole generation has passed since the death of the Mule. What of the future, then, now that he has come and gone? He interrupted Seldon's Plan and seemed to have burst it to fragments, yet as soon as he died, the Foundation rose again, like a nova from the dead ashes of a dying star.

(She had made that up herself.)

Once again, the planet Terminus houses the center of a commercial federation almost as great and as rich as before the conquest, and even more peaceful and democratic.

"Is this planned? Is Seldon's great dream still alive, and will a Second Galactic Empire yet be formed six hundred years from now? I, myself, believe so, because

(This was the important part. Miss Erlking always had those large, ugly red-pencil scrawls that went: 'But this is only descriptive. What are your personal reactions? Think! Express yourself! Penetrate your own soul!' Penetrate your own soul. A lot she knew about souls, with her lemon face that never smiled in its life-)

never at any time has the political situation been so favorable. The old Empire is completely dead and the period of the Mule's rule put an end to the era of warlords that preceded him. Most of the surrounding portions of the Galaxy are civilized and peaceful.

"Moreover the internal health of the Foundation is better than ever before. The despotic times of the pre-Conquest hereditary mayors have given way to the democratic elections of early times. There are no longer dissident worlds of independent Traders; no longer the injustices and dislocations that accompanied accumulations of great wealth in the hands of a few.

"There is no reason, therefore, to fear failure, unless it is true that the Second Foundation itself presents a danger. Those who think so have no evidence to back their claim, but merely vague fears and superstitions. I think that our confidence in ourselves, in our nation, and in Hari Seldon's great Plan should drive from our hearts and minds all uncertainties and

(Hm-m-m. This was awfully corny, but something like this was expected at the end.)

so I say-"

That is as far as "The Future of Seldon's Plan" got, at that moment, because there was the gentlest little tap on the window, and when Arcadia shot up to a balance on one arm of the chair, she found herself confronted by a smiling face beyond the glass, its even symmetry of feature interestingly accentuated by the short, vertical fine of a finger before its lips.

With the slight pause necessary to assume an attitude of bepuzzlement, Arcadia dismounted from the armchair, walked to the couch that fronted the wide window that held the apparition and, kneeling upon it, stared out thoughtfully.

The smile upon the man's face faded quickly. While the fingers of one hand tightened whitely upon the sill, the other made a quick gesture. Arcadia obeyed calmly, and closed the latch that moved the lower third of the window smoothly into its socket in the wall, allowing the warm spring air to interfere with the conditioning within.

"You can't get in," she said, with comfortable smugness. "The windows are all screened, and keyed only to people who belong here. If you come in, all sorts of alarms will break loose." A pause, then she added, "You look sort of silly balancing on that ledge underneath the window. If you're not careful, you'll fall and break your neck and a lot of valuable flowers."

"In that case," said the man at the window, who had been thinking that very thing – with a slightly different arrangement of adjectives– "will you shut off the screen and let me in?"

"No use in doing that'" said Arcadia. "You're probably thinking of a different house, because I'm not the kind of girl who lets strange men into their… her bedroom this time of night." Her eyes, as she said it, took on a heavy-lidded sultriness – or an unreasonable facsimile thereof.

All traces of humor whatever had disappeared from the young stranger's face. He muttered, "This is Dr. Darell's house, isn't it?"

"Why should I tell you?"

"Oh, Galaxy– Good-by-"

"If you jump off, young man, I will personally give the alarm." (This was intended as a refined and sophisticated thrust of irony, since to Arcadia's enlightened eyes, the intruder was an obviously mature thirty, at least – quite elderly, in fact.)

Quite a pause. Then, tightly, he said, "Well, now, look here, girlie, if you don't want me to stay, and don't want me to go, what do you want me to do?"

"You can come in, I suppose. Dr. Darell does live here. I’ll shut off the screen now."

Warily, after a searching look, the young man poked his hand through the window, then hunched himself up and through it. He brushed at his knees with an angry, slapping gesture, and lifted a reddened face at her.

"You're quite sure that your character and reputation won't suffer when they find me here, are you?"

"Not as much as yours would, because just as soon as I hear footsteps outside, I'll just shout and yell and say you forced your way in here."

"Yes?" he replied with heavy courtesy, "And how do you intend to explain the shut-off protective screen?"

"Poof! That would be easy. There wasn't any there in the first place."

The man's eyes were wide with chagrin. "That was a bluff? How old are you, kid?"

"I consider that a very impertinent question, young man. And I am not accustomed to being addressed as 'kid.'"

"I don't wonder. You're probably the Mule's grandmother in disguise. Do you mind if I leave now before you arrange a lynching party with myself as star performer?"

"You had better not leave – because my father's expecting you."

The man's look became a wary one, again. An eyebrow shot up as he said, lightly, "Oh? Anyone with your father?'

"No."

"Anyone called on him lately?'

"Only tradespeople – and you."

"Anything unusual happen at all?"

"Only you."

"Forget me, will you? No, don't forget me. Tell me, how did you know your father was expecting me?"

"Oh, that was easy. Last week, he received a Personal Capsule, keyed to him personally, with a self-oxidizing message, you know. He threw the capsule shell into the Trash Disinto, and yesterday, he gave Poli – that's our maid, you see – a month's vacation so she could visit her sister in Terminus City, and this afternoon, he made up the bed in the spare room. So I knew he expected somebody that I wasn't supposed to know anything about. Usually, he tells me everything."

"Really! I'm surprised he has to. I should think you'd know everything before he tells you."

'I usually do." Then she laughed. She was beginning to feel very much at ease. The visitor was elderly, but very distinguished-looking with curly brown hair and very blue eyes. Maybe she could meet somebody like that again, sometimes, when she was old herself.

"And just how," he asked, "did you know it was I he expected."

"Well, who else could it be? He was expecting somebody in so secrety a way, if you know what I mean – and then you come gumping around trying to sneak through windows, instead of walking through the front door, the way you would if you had any sense." She remembered a favorite line, and used it promptly. "Men are so stupid!"

"Pretty stuck on yourself, aren't you, kid? I mean, Miss. You could be wrong, you know. What if I told you that all this is a mystery to me and that as far as I know, your father is expecting someone else, not me."

"Oh, I don't think so. I didn't ask you to come in, until after I saw you drop your briefcase."

"My what?"

"Your briefcase, young man. I'm not blind. You didn't drop it by accident, because you looked down first, so as to make sure it would land right. Then you must have realized it would land just under the hedges and wouldn't be seen, so you dropped it and didn't look down afterwards. Now since you came to the window instead of the front door, it must mean that you were a little afraid to trust yourself in the house before investigating the place. And after you had a little trouble with me, you took care of your briefcase before taking care of yourself, which means that you consider whatever your briefcase has in it to be more valuable than your own safety, and that means that as long as you're in here and the briefcase is out there and we know that it's out there, you're probably pretty helpless."

She paused for a much-needed breath, and the man said, grittily, "Except that I think I'll choke you just about medium dead and get out of here, with the briefcase."

"Except, young man, that I happen to have a baseball bat under my bed, which I can reach in two seconds from where I'm sitting, and I'm very strong for a girl."

Impasse. Finally, with a strained courtesy, the "young man" said, "Shall I introduce myself, since we're being so chummy. I'm Pelleas Anthor. And your name?"

"I'm Arca– Arkady Darell. Pleased to meet you."

"And now Arkady, would you be a good little girl and call your father?"

Arcadia bridled. "I'm not a little girl. I think you're very rude – especially when you're asking a favor."

Pelleas Anthor sighed. "Very well. Would you be a good, kind, dear, little old lady, just chock full of lavender, and call your father?"

"That's not what I meant either, but I’ll call him. Only not so I'll take my eyes off you, young man." And she stamped on the floor.

There came the sound of hurrying footsteps in the hall, and the door was flung open.

"Arcadia-" There was a tiny explosion of exhaled air, and Dr. Darell said, "Who are you, sir?"

Pelleas sprang to his feet in what was quite obviously relief. "Dr. Toran Darell? I am Pelleas Anthor. You've received word about me, I think. At least, your daughter says you have."

"My daughter says I have?" He bent a frowning glance at her which caromed harmlessly off the wide-eyed and impenetrable web of innocence with which she met the accusation.

Dr. Darell said, finally: "I have been expecting you. Would you mind coming down with me, please?" And he stopped as his eye caught a flicker of motion, which Arcadia caught simultaneously.

She scrambled toward her Transcriber, but it was quite useless, since her father was standing right next to it. He said, sweetly, "You've left it going all this time, Arcadia."

"Father," she squeaked, in real anguish, "it is very ungentlemanly to read another person's private correspondence, especially when it's talking correspondence."

"Ah," said her father, "but 'talking correspondence' with a strange man in your bedroom! As a father, Arcadia, I must protect you against evil."

"Oh, golly – it was nothing like that."

Pelleas laughed suddenly, "Oh, but it was, Dr. Darell. The young lady was going to accuse me of all sorts of things, and I must insist that you read it, if only to clear my name."

"Oh-" Arcadia held back her tears with an effort. Her own father didn't even trust her. And that darned Transcriber– If that silly fool hadn't come gooping at the window, and making her forget to turn it off. And now her father would be making long, gentle speeches about what young ladies aren't supposed to do. There just wasn't anything they were supposed to do, it looked like, except choke and die, maybe.

"Arcadia," said her father, gently, "it strikes me that a young lady-"

She knew it. She knew it.

"-should not be quite so impertinent to men older than she is."

"Well, what did he want to come peeping around my window for? A young lady has a right to privacy– Now I'll have to do my whole darned composition over."

"It's not up to you to question his propriety in coming to your window. You should simply not have let him in. You should have called me instantly – especially if you thought I was expecting him."

She said, peevishly, "It's just as well if you didn't see him – stupid thing. Hell give the whole thing away if he keeps on going to windows, instead of doors."

"Arcadia, nobody wants your opinion on matters you know nothing of."

"I do, too. It's the Second Foundation, that's what it is."

There was a silence. Even Arcadia felt a little nervous stirring in her abdomen.

Dr. Darell said, softly, "Where have you heard this?"

"Nowheres, but what else is there to be so secret about? And you don't have to worry that I’ll tell anyone."

"Mr. Anthor," said Dr. Darell, "I must apologize for all this."

"Oh, that's all right," came Anthor's rather hollow response. "It's not your fault if she's sold herself to the forces of darkness. But do you mind if I ask her a question before we go. Miss Arcadia-"

"What do you want?"

"Why do you think it is stupid to go to windows instead of to doors?"

"Because you advertise what you're trying to hide, silly. If I have a secret, I don't put tape over my mouth and let everyone know I have a secret. I talk just as much as usual, only about something else. Didn't you ever read any of the sayings of Salvor Hardin? He was our first Mayor, you know."

"Yes, I know."

"Well, he used to say that only a lie*** that wasn't ashamed of itself could possibly succeed. He also said that nothing had to be true, but everything had to sound true. Well, when you come in through a window, it's a lie that's ashamed of itself and it doesn't sound true."

"Then what would you have done?"

"If I had wanted to see my father on top secret business, I would have made his acquaintance openly and seen him about all sorts of strictly legitimate things. And then when everyone knew all about you and connected you with my father as a matter of course, you could be as top secret as you want and nobody would ever think of questioning it."

Anthor looked at the girl strangely, then at Dr. Darell. He said, "Let's go. I have a briefcase I want to pick up in the garden. Wait! Just one last question. Arcadia, you don't really have a baseball bat under your bed, do you?"

"No! I don't."

"Hah. I didn't think so."

Dr. Darell stopped at the door. "Arcadia," he said, "when you rewrite your composition on the Seldon Plan, don't be unnecessarily mysterious about your grandmother. There is no necessity to mention that part at all."

He and Pelleas descended the stairs in silence. Then the visitor asked in a strained voice, "Do you mind, sir? How old is she?"

"Fourteen, day before yesterday."

"Fourteen? Great Galaxy– Tell me, has she ever said she expects to marry some day?"

"No, she hasn't. Not to me."

Well, if she ever does, shoot him. The one she's going to marry, I mean." He stared earnestly into the older man's eyes. "I'm serious. Life could hold no greater horror than living with what she'll be like when she's twenty. I don't mean to offend you, of course."

"You don't offend me. I think I know what you mean."

Upstairs, the object of their tender analyses faced the Transcriber with revolted weariness and said, dully: "Thefutureofseldonsplan." The Transcriber with infinite aplomb, translated that into elegantly, complicated script capitals as:

"The Future of Seldon's Plan."

8. Seldon's Plan

MATHEMATICS The synthesis of the calculus of n-variables and of n-dimensional geometry is the basis of what Seldon once called "my little algebra of humanity"… Encyclopedia Galactica

Consider a room!

The location of the room is not in question at the moment. It is merely sufficient to say that in that room, more than anywhere, the Second Foundation existed.

It was a room which, through the centuries, had been the abode of pure science – yet it had none of the gadgets with which, through millennia of association, science has come to be considered equivalent. It was a science, instead, which dealt with mathematical concepts only, in a manner similar to the speculation of ancient, ancient races in the primitive, prehistoric days before technology had come to be; before Man had spread beyond a single, now-unknown world.

For one thing, there was in that room – protected by a mental science as yet unassailable by the combined physical might of the rest of the Galaxy – the Prime Radiant, which held in its vitals the Seldon Plan – complete.

For another, there was a man, too, in that room – The First Speaker.

He was the twelfth in the line of chief guardians of the Plan, and his title bore no deeper significance than the fact that at the gatherings of the leaders of the Second Foundation, he spoke first.

His predecessor had beaten the Mule, but the wreckage of that gigantic struggle still littered the path of the Plan– For twenty-five years, he, and his administration, had been trying to force a Galaxy of stubborn and stupid human beings back to the path-It was a terrible task.

The First Speaker looked up at the opening door. Even while, in the loneliness of the room, he considered his quarter century of effort, which now so slowly and inevitably approached its climax; even while he had been so engaged, his mind had been considering the newcomer with a gentle expectation. A youth, a student, one of those who might take over, eventually.

The young man stood uncertainly at the door, so that the First Speaker had to walk to him and lead him in, with a friendly hand upon the shoulder.

The Student smiled shyly, and the First Speaker responded by saying, "First, I must tell you why you are here."

They faced each other now, across the desk. Neither was speaking in any way that could be recognized as such by any man in the Galaxy who was not himself a member of the Second Foundation.

Speech, originally, was the device whereby Man learned, imperfectly, to transmit the thoughts and emotions of his mind. By setting up arbitrary sounds and combinations of sounds to represent certain mental nuances, be developed a method of communication – but one which in its clumsiness and thick-thumbed inadequacy degenerated all the delicacy of the mind into gross and guttural signaling.

Down – down – the results can be followed; and all the suffering that humanity ever knew can be traced to the one fact that no man in the history of the Galaxy, until Hari Seldon, and very few men thereafter, could really understand one another. Every human being lived behind an impenetrable wall of choking mist within which no other but he existed. Occasionally there were the dim signals from deep within the cavern in which another man was located-so that each might grope toward the other. Yet because they did not know one another, and could not understand one another, and dared not trust one another, and felt from infancy the terrors and insecurity of that ultimate isolation – there was the hunted fear of man for man, the savage rapacity of man toward man.

Feet, for tens of thousands of years, had clogged and shuffled in the mud – and held down the minds which, for an equal time, had been fit for the companionship of the stars.

Grimly, Man had instinctively sought to circumvent the prison bars of ordinary speech. Semantics, symbolic logic, psychoanalysis – they had all been devices whereby speech could either be refined or by-passed.

Psychohistory had been the development of mental science, the final mathematicization thereof, rather, which had finally succeeded. Through the development of the mathematics necessary to understand the facts of neural physiology and the electrochemistry of the nervous system, which themselves had to be, had to be, traced down to nuclear forces, it first became possible to truly develop psychology. And through the generalization of psychological knowledge from the individual to the group, sociology was also mathematicized.

The larger groups; the billions that occupied planets; the trillions that occupied Sectors; the quadrillions that occupied the whole Galaxy, became, not simply human beings, but gigantic forces amenable to statistical treatment – so that to Hari Seldon, the future became clear and inevitable, and the Plan could be set up.

The same basic developments of mental science that had brought about the development of the Seldon Plan, thus made it also unnecessary for the First Speaker to use words in addressing the Student.

Every reaction to a stimulus, however slight, was completely indicative of all the trifling changes, of all the flickering currents that went on in another's mind. The First Speaker could not sense the emotional content of the Student's instinctively, as the Mule would have been able to do – since the Mule was a mutant with powers not ever likely to become completely comprehensible to any ordinary man, even a Second Foundationer – rather he deduced them, as the result of intensive training.

Since, however, it is inherently impossible in a society based on speech to indicate truly the method of communication of Second Foundationers among themselves, the whole matter will be hereafter ignored. The First Speaker will be represented as speaking in ordinary fashion, and if the translation is not always entirely valid, it is at least the best that can be done under the circumstances.

It will be pretended therefore, that the First Speaker did actually say, "First, I must tell you why you are here," instead of smiling just so and lifting a finger exactly thus.

The First Speaker said, "You have studied mental science hard and well for most of your life. You have absorbed all your teachers could give you. It is time for you and a few others like yourself to begin your apprenticeship for Speakerhood."

Agitation from the other side of the desk.

"No – now you must take this phlegmatically. You had hoped you would qualify. You had feared you would not. Actually, both hope and fear are weaknesses. You knew you would qualify and you hesitate to admit the fact because such knowledge might stamp you as cocksure and therefore unfit. Nonsense! The most hopelessly stupid man is he who is not aware that he is wise. It is part of your qualification that you knew you would qualify."

Relaxation on the other side of the desk.

"Exactly. Now you feel better and your guard is down. You are fitter to concentrate and fitter to understand. Remember, to be truly effective, it is not necessary to hold the mind under a tight, controlling barrier which to the intelligent probe is as informative as a naked mentality. Rather, one should cultivate an innocence, an awareness of self, and an unself-consciousness of self which leaves one nothing to hide. My mind is open to you. Let this be so for both of us."

He went on. "It is not an easy thing to be a Speaker. It is not an easy thing to be a Psychohistorian in the first place; and not even the best Psychohistorian need necessarily qualify to be a Speaker. There is a distinction here. A Speaker must not only be aware of the mathematical intricacies of the Seldon Plan; he must have a sympathy for it and for its ends. He must love the Plan; to him it must be life and breath. More than that it must even be as a living friend.

"Do you know what this is?"

The First Speaker's hand hovered gently over the black, shining cube in the middle of the desk. It was featureless.

"No, Speaker, I do not."

"You have heard of the Prime Radiant?"

"This?" – Astonishment.

"You expected something more noble and awe-inspiring? Well, that is natural. It was created in the days of the Empire, by men of Seldon's time. For nearly four hundred years, it has served our needs perfectly, without requiring repairs or adjustment. And fortunately so, since none of the Second Foundation is qualified to handle it in any technical fashion." He smiled gently. "Those of the First Foundation might be able to duplicate this, but they must never know, of course."

He depressed a lever on his side of the desk and the room was in darkness. But only for a moment, since with a gradually livening flush, the two long walls of the room glowed to life. First, a pearly white, unrelieved, then a trace of faint darkness here and there, and finally, the fine neatly printed equations in black, with an occasional red hairline that wavered through the darker forest like a staggering rillet.

"Come, my boy, step here before the wall. You will not cast a shadow. This light does not radiate from the Radiant in an ordinary manner. To tell you the truth, I do not know even faintly by what medium this effect is produced, but you will not cast a shadow. I know that."

They stood together in the light. Each wall was thirty feet long, and ten high. The writing was small and covered every inch.

"This is not the whole Plan," said the First Speaker. "To get it all upon both walls, the individual equations would have to be reduced to microscopic size – but that is not necessary. What you now see represents the main portions of the Plan till now. You have learned about this, have you not?"

"Yes, Speaker, I have."

"Do you recognize any portion."

A slow silence. The student pointed a finger and as he did so, the line of equations marched down the wall, until the single series of functions he had thought of – one could scarcely consider the quick, generalized gesture of the finger to have been sufficiently precise – was at eye-level.

The First Speaker laughed softly, "You will find the Prime Radiant to be attuned to your mind. You may expect more surprises from the little gadget. What were you about to say about the equation you have chosen?"

"It," faltered the Student, "is a Rigellian integral, using a planetary distribution of a bias indicating the presence of two chief economic classes on the planet, or maybe a Sector, plus an unstable emotional pattern."

"And what does it signify?"

"It represents the limit of tension, since we have here" – he pointed, and again the equations veered – "a converging series."

"Good," said the First Speaker. "And tell me, what do you think of all this. A finished work of art, is it not?"

"Definitely!"

"Wrong! It is not." This, with sharpness. "It is the first lesson you must unlearn. The Seldon Plan is neither complete nor correct. Instead, it is merely the best that could be done at the time. Over a dozen generations of men have pored over these equations, worked at them, taken them apart to the last decimal place, and put them together again. They've done more than that. They've watched nearly four hundred years pass and against the predictions and equations, they've checked reality, and they have learned.

"They have learned more than Seldon ever knew, and if with the accumulated knowledge of the centuries we could repeat Seldon's work, we could do a better job. Is that perfectly clear to you?"

The Student appeared a little shocked.

"Before you obtain your Speakerhood," continued the First Speaker, "you yourself will have to make an original contribution to the Plan. It is not such great blasphemy. Every red mark you see on the wall is the contribution of a man among us who lived since Seldon. Why… why-" He looked upward, "There!"

The whole wall seemed to whirl down upon him.

"This," he said, "is mine." A fine red line encircled two forking arrows and included six square feet of deductions along each path. Between the two were a series of equations in red.

"It does not," said the Speaker, "seem to be much. It is at a point in the Plan which we will not reach yet for a time as long as that which has already passed. It is at the period of coalescence, when the Second Empire that is to be is in the grip of rival personalities who will threaten to pull it apart if the fight is too even, or clamp it into rigidity, if the fight is too uneven. Both possibilities are considered here, followed, and the method of avoiding either indicated.