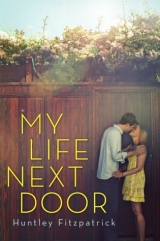

Текст книги "My Life Next Door"

Автор книги: Huntley Fitzpatrick

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 18 (всего у книги 19 страниц)

“There’s a witness, and it’s me,” I point out.

Clay tilts his head, looking at me, nods once. “Right. I forgot that you had no problem betraying your mom.”

“That line’s straight out of Cheesy Villain School too,” I tell him.

Mom buries her head in her hands, her shoulders shaking. “There’s no point,” she says. “The Garretts will hear and they’ll do what they’ll do and there’s nothing to be done about it.” She lifts her face, teary, to Clay. “Thank you for trying, though, honey.”

Reaching into his pocket, he pulls out a handkerchief and gently dabs her lashes dry. “Grace, sugar, there’s always a way to play it. Have a little faith. I’ve been in this game a while.” Mom sniffs, her eyes cast down. Jase and I exchange disbelieving looks. Game?

Clay hooks his thumbs in his pockets, coming around in front of the desk again, starting to pace. “Okay, Grace. What if you call the press conference– with the Garretts. You speak first. Confess everything.

This terrible thing happened. You were wracked by guilt, but because your daughter and the Garrett boy were personally involved”—he pauses to smile at us, as if bestowing his blessing—“you kept quiet. You didn’t want to taint your daughter’s first true love. Everyone will identify with that—we all had that—and if we didn’t, we sure wish we had. So you kept quiet for the sake of your daughter, but…” He paces a little more, brow puckered. “… you couldn’t honorably represent the people with something of this magnitude on your conscience. This way’s riskier, but I’ve seen it work. Everybody loves a repentant sinner. You’d have your family there—your daughters standing by their mom. The Garretts, salt-of-the-earth types, the young lovers—”

“Wait just a minute here,” Jase interrupts. “What Sam and I feel about each other isn’t some”—he pauses, searching for words—“marketing tool.”

Clay tosses him an amused smile. “With all due respect, son, everyone’s feelings are a marketing tool.

That’s what marketing is all about—hitting people in the gut. Here we have the young lovers, the working family struck with an unexpected crisis—” He stops pacing, grins. “Gracie, I’ve got it. You could also use the moment to introduce some new legislation to help working families. Nothing too radical, just something to say Grace Reed has come through this experience with even more compassion for the people she serves. This all makes perfect sense to me now. We could get Mr. Garrett—the wounded blue-collar man—to say he wouldn’t want Senator Reed’s good work to be destroyed by this.” I look at Jase. His lips are slightly parted and he’s staring at Clay in fascination. Sort of the way you’d look at a striking cobra.

“Then you could appeal to the people, ask them to call or write or send e-mails directly to your office if they still want you as their senator. We in the business call that the ‘Send in Your Box Tops’ speech.

People get all het up and excited because they feel part of the process. Your office gets besieged—you lay low for a few days, then call another conference and humbly thank the citizens of Connecticut for their faith in you and pledge to be worthy of it. It’s a killer moment, and at least fifty percent of the time, it makes you a shoo-in at election time,” he concludes, grinning at Mom triumphantly.

She too is staring at him with her mouth open. “But…” she says.

Jase and I are silent.

“C’mon,” Clay urges. “It makes perfect sense. It’s the logical way to go.” Jase gets to his feet. I am pleased to notice that he’s taller than Clay. “Everything you say makes sense, sir. I guess it’s logical. But with all due respect, you’re out of your fucking mind. Come on, Sam. Let’s go home.”

Chapter Fifty

The day has dimmed into twilight by the time we leave the house. Jase’s long legs eat up the driveway and I’m nearly jogging to keep up with him. We’ve almost reached the Garretts’ kitchen steps before I come to a standstill. “Wait.”

“Sorry. I was practically towing you along. I feel like I need a shower after all that. Holy hell, Sam.

What was that?”

“I know,” I say. “I’m sorry.” How could Clay have said all that, smooth as Kentucky bourbon, and Mom just sitting there as if she’d already drunk the bottle? I rub my forehead. “Sorry,” I mutter again.

“It’d be good if you’d stop apologizing right about now,” he tells me.

I take a deep breath, looking down at his shoes. “It’s about all I’ve got. To fix things.” Jase has these huge feet. They dwarf mine. He’s wearing his usual sneakers, and I’m in flip-flops. We stand toe to toe for a minute, then he edges one big foot in between my smaller ones.

“You were great back there,” I say, hanging on to what’s true.

He jams his hands in his pockets. “Are you kidding? You were the one who called him on his bullshit every time I started to get hypnotized by his wrong-is-right, up-is-down arguments.”

“Only because I’d heard ’em all before. It took me weeks to see through the hypnotism.” Jase shakes his head. “Suddenly the whole thing was a photo op. How’d he even do that? I get why Tim was so mental about that guy.”

We’re quiet, looking back at my house.

“My mother,” I start, then stop. Despite what Clay says, that I’m a casual turncoat daughter, this isn’t easy. How can Jase ever know, really understand, all those years when she did teach us well? Or the best she could.

But he waits, patient and thoughtful, until I can say more.

“She’s not a monster. I want you to know that. It doesn’t really matter because what she did was so wrong. But she’s not an evil person. Just”—my voice wobbles—“not all that strong.” Jase reaches out, pulls the elastic band from my hair, letting it slip free over my shoulders. I’ve missed that gesture so much.

I didn’t look over at Mom when we walked out. No point to it. Even before, when I did look at her face, I had no idea what to read there. “I’m guessing Mom won’t want me showing up for dinner at the B

and T tonight. Or when I’ll be welcome at home.”

“Well, you’re welcome in mine.” He draws me in close, hipbone to hipbone. “We can just listen to that suggestion of George’s. You can move into my room, sleep in my bed. I thought that was a brilliant idea the minute he came up with it.”

“George just mentioned the room, not the bed,” I say.

“He did tell you I never peed in my bed. That was incentive right there.”

“There are those of us who would take clean sheets as a given. We might need more incentive.”

“I’ll see what I can do,” Jase says.

“Sailor Supergirl!” George shouts through the screen. “I’m going to have a baby brother! Or a sister, but I want a brother. We have a picture. Come see, come see, come see!” I turn to Jase. “It’s confirmed, then?”

“Alice shook it out of Mom with her ninja nurse tactics. Kind of like Tim with you, I guess.” George returns to the screen, squashing some printout against it. “See. This is my baby brother. He kinda looks like a storm cloud now, but he’s gonna change a lot because that’s what Mommy says babies do best of anything..”

Jase says, “Stand back, buddy,” nudging the door open wide enough for us to pass through.

I haven’t seen Joel for a while. Where he once projected all laidback cool, now he’s edgy, stalking around the kitchen. Alice churns out pancakes and the younger kids sit at the table, watching as if their older siblings are Nickelodeon.

We walk in just as Joel’s asking, “Why does Dad have that thing in his windpipe? He was breathing fine. Are we going backward?”

Alice edges a small, flat, very dark pancake off the pan. “The nurses explained all this.”

“Not in English. Please, Al, translate?”

“It’s because of the deep vein thrombosis—kind of a clot he got. They put him in those inflatable boots for that, because they didn’t want to give him anti-coag drugs—”

“English,” Joel reiterates.

“Stuff that makes his blood thinner. Because of the head injury. They put him in the boots, but someone ignored or didn’t notice the order that they were to go on and off every two hours.”

“Can we sue this someone?” Joel asks angrily. “He was talking, getting better, now he’s worse off than ever.”

Alice chips four more skinny charcoal briquette-looking pancakes off the pan, then adds some butter.

“It’s good they caught it, Joey.” She looks up, seeming to notice for the first time that I’m standing beside Jase.

“What are you doing here?”

“She belongs here,” Jase says. “Drop it, Alice.”

Andy starts to cry. “He doesn’t look like Dad anymore.”

“He does so. Look like Dad,” George insists stoutly. He hands me the computer printout. “This is our baby.”

“He’s very cute,” I tell George, scrutinizing what does, indeed, look like a hurricane off the Bahamas.

“Dad’s all skinny,” Andy continues. “He smells like the hospital. Looking at him freaks me out. It’s like he’s this old man suddenly? I don’t want an old man. I want Daddy.” Jase winks at her. “He just needs more of Alice’s pancakes, Ands. He’ll be fine then.”

“Alice makes the worst pancakes known to humankind,” Joel observes. “These are like coasters.”

“I’m cooking,” Alice observes sharply. “You’re what? Critiquing? Doing a restaurant review? Go get takeout, if you want to be useful. Ass-hat.”

Jase glances around at his siblings, then back at me. I understand his hesitation. Though things at the Garretts’ are unbalanced—mealtimes off, everyone more cranky, it all still seems normal. Not right to detonate the bomb of some big announcement. Like barging into Mr. and Mrs. Capulet’s argument about whether they are overpaying the nurse with “We now interrupt this ordinary life with an epic tragedy.”

“Yo.” The screen door opens, letting in Tim, laden with four pizza boxes, two cartons of ice cream, and the blue-zipped bag in which the Garretts keep the contents of the till from the hardware store balanced on top.

“Hello, hot Alice. Wanna put on your uniform and check my pulse?”

“I never play games with little boys,” Alice snaps without turning around from her position at the stove, where she’s still doggedly turning out pancakes.

“You should. We’re full of energy. And mischief.”

Alice doesn’t bother to answer.

Taking the boxes, Jase begins piling them on the table, batting away his younger siblings’ questing hands. “Wait till I get plates, guys! Jeez. How was the take at the end of the day?”

“Actually, surprisingly good.” Tim hauls a wad of paper napkins out of his pocket and fans them out on the table. “We sold a wood chipper—that freaking big one in the back that was taking up all the space.”

“No way.” Jase pulls a gallon of milk out of the fridge, carefully distributing it into paper cups.

“Two-thousand-dollar way.” Tim flips slices of pizza onto plates, shoving them in front of Duff, Harry, Andy, George, and the still-scowling Joel.

“Hey, kid. Good to see you here.” Tim smiles at me. “Back where you belong, and all that crap.”

“Mines!” Patsy shouts, pointing at Tim. He goes to her, rumples her scanty hair.

“See, hot Alice? Even the very young feel the pull of my magnetism. It’s like an irresistible urge, a force like gravity, or—”

“Poop!”

“Or that.” Tim removes Patsy’s hand, which is now tugging up his shirt. Poor girl. She really hates drinking from bottles.

He grins at Alice. “So, hot Alice. Whaddya think? How about putting on that uniform and checking my reflexes?”

“Stop putting the moves on my sister in our kitchen, Tim. Jesus. Just so you know, Alice’s nurse’s uniform is a pair of green scrubs. She looks like Gumby,” Jase says, returning the gallon of milk to the fridge.

“I’m starving, but I don’t want pizza,” Duff says heavily. “That’s all we ever eat anymore. I’m sick of pizza and Cheerios, and those used to be my two favorite things on the planet.”

“I used to think it would be fun to watch TV all the time,” Harry says. “But it’s not, it’s boring.”

“I stayed up until three last night, watching Jake Gyllenhaal movies, even the R-rated ones,” Andy offers. “Nobody even noticed or told me to go to bed.”

“Are we all sharing grievances now?” Joel says. “Should I get out the talking stick?”

“Well, actually,” Jase begins, and then there’s a knock on the door.

“Joel, did you order out even though you knew I was making pancakes?” Alice asks angrily.

Joel raises his hands in self-defense. “God knows I wanted to, but I hadn’t gotten around to it. I swear.” The knock sounds again, and Duff opens the screen door to let in…my mother.

“I wondered if my daughter was here.” Her gaze drifts over everyone at the table, Patsy with her hair smeared with butter, syrup, and tomato sauce; George without his shirt, little rivulets of syrup edging down his chest; Harry lunging for more pizza; Duff at his most truculent, the teary Andy. Jase, who freezes in his tracks.

“Hi, Mom.”

Her eyes settle on me. “I thought I’d find you here. Hi, sweetheart.”

“Yo Gracie.” Tim drags an armchair from the living room to the kitchen island. “Take a load off. Let your hair down. Have a slice.” He cuts a glance at my face, then Jase’s, eyebrows lifting.

Jase is still staring at Mom, that confused look he had in her office returning. My mother regards the boxes of pizza as though they are alien artifacts from Roswell, New Mexico. Her preferred pizza toppings, I know, are pesto, artichoke hearts, and shrimp. Nonetheless, she sinks into the chair. “Thank you.”

I look at her. This is neither the broken woman in the silk robe nor the brittle hostess offering Jase a beer. There’s something in her face I haven’t seen before. I glance over to find Jase still studying her too, his expression impassive.

“So, you’re Sailor Supergirl’s mommy.” George struggles to talk around a mouth full of pizza. “We never saw you up close before. Only on TV.”

My mother gives him a tiny smile. “What’s your name?”

I rush through introductions. She looks so stiff and uncomfortable, immaculate and out of place in the comfortable chaos of this kitchen. “Should we go home, Mom?” She shakes her head. “No. I’d like to meet Jase’s family. Goodness. Is this all of you?”

“’Cept my daddy, cause he’s in the hostible,” George says chattily, getting up from the table and circling over to Mom. “And Mommy, cause she’s taking a nap. And our new baby, because he’s in Mommy’s belly drinking her blood.”

Mom pales.

Rolling her eyes, Alice says, “George, that’s not how it works. I explained when you asked how the new baby ate. Nutrients go through the umbilical cord, along with Mom’s blood, so—”

“I know how the baby got in there,” announces Harry. “Someone told me at sailing camp. See, the dad puts—”

“Okay, guys, enough,” Jase interrupts. “Settle down.” He looks over at Mom again, drumming his index finger on the countertop.

Silence.

A little awkward. Not to mention unusual. George, Harry, Duff, and Andy are busy eating. Joel has unzipped the cash register bag and is sorting through the bills, separating by denomination. Tim’s opened one of the cartons of ice cream and is eating directly out of it.

Which gets Alice’s attention. “Do you have any idea how unsanitary that is?” He drops the spoon guiltily. “Sorry. I didn’t think. I just needed sugar. All I do these days is eat sweets.

I may be sober, and not smoking much, but morbid obesity is my future.” Alice actually smiles at him. “That’s part of the withdrawal process, Tim. Completely normal. Just…

get yourself a bowl, okay?”

Tim grins back at her and there’s this funny stillness there before Alice turns away, reaching into a drawer. “Here.”

“I want ice cream. I want ice cream.” George bangs his own spoon on the table.

Patsy, getting into the spirit, whacks her high chair with her hands. “Boob,” she yells. “Poop.” Mom frowns.

“Her first words,” I explain hastily. Then shame prickles my face. Why do I feel as though I have to explain away Patsy?

“Ah.”

Jase meets my eyes. His are stormy with bafflement and pain so intense it hits me like a slap.

What is she doing here now? Jase and I were fine, we were connected, and here she is. Why?

He jerks his head toward the door. “We’d better get some more ice cream from the freezer in the garage. Come on, Sam.”

There are two full cartons on the table. Alice looks down at them, then at Jase. “But—” she starts.

He shakes his head at her. “Sam?”

I follow him out. I can see a muscle jump in his jawline; feel the tension in the set of his shoulders as though they are part of my own body.

As soon as we’ve cleared the steps, he wheels on me. “What is this? Why is she here?” I stumble back. “I don’t know,” I say. My mom’s acting so normal, so calm, the friendly neighbor dropping by. But nothing is normal. How can she be calm?

“Is this more of Clay’s bullshit?” Jase demands. “Is he having her come over here and act all nicey-nice, before everyone else finds out?”

My eyes prickle, tears so close. “I don’t know,” I say again.

“Like maybe my family will think that this sweet lady could never do something so bad, and I’ve just lost it or something and—”

I grab his hand.

“I don’t know,” I whisper. Could this be yet another part of Clay’s game? Of course it could. I’d been thinking, somehow, that Mom was making a gesture in there…a peace offering, but maybe it is just another political tactic. My stomach coils. I don’t know what to think. I don’t know what to feel. The tears I’ve been fending off spill over. I scrub at my cheeks angrily.

“I’m sorry,” Jase says, pulling me to him so my cheek rests against his chest. “Of course you don’t. I just…seeing her sitting there in the kitchen, eating pizza as if everything’s all great, it makes me—”

“Sick,” I finish for him, shutting my eyes.

“For you too. Not just Dad. For you too, Sam.”

I want to argue, repeat again that she’s not a bad person. But if she really has come over here at Clay’s bidding to show the “softer side of Grace,” then…

“Got that ice cream?” Alice calls out the door. “I didn’t think it was possible, but we’ll actually be needing it.”

“Uh…just a sec,” Jase calls back, hastily lifting the garage door. He reaches into the Garretts’ freezer case, always loaded from Costco, and takes out a carton. “Let’s get back in before they eat the bowls.” He tries for his old, easy smile, falls short.

When we return to the kitchen, George is saying to Mom, “I like this cereal called Gorilla Munch on top of my ice cream. It’s not really made of gorillas.”

“Oh. Well. Good.”

“It’s really just peanut butter and healthy stuff.” George searches around in the box, tipping it, then heaps cereal into his bowl. “But if you buy boxes of cereal, you can save gorillas. And that’s really good,

’cause otherwise they can get instinct.”

My mother looks at me for translation. Or maybe salvation.

“Extinct,” I supply.

“That’s what I meant.” George pours milk on top of his cereal and ice cream, then stirs it vigorously.

“That means they don’t mate enough and then they are dead forever.” Silence falls again. Heavy silence. Dead forever. That phrase seems to reverberate in the air, at least for me. Mr. Garrett lying facedown in the rain, that image Jase added to the echo of that sickening thud.

Does Mom see it too? She puts down her slice of pizza, her fingers tight on a paper towel as she dabs at her lips. Jase is staring at the floor.

My mother stands up so abruptly that her chair almost overturns. “Samantha, will you come outside with me for a moment?”

Dread snags at me. She’s not going to march me home to face Clay’s arm-twisting again. Please no. I glance at Jase.

Mom bends over the table so she’s eye to eye with George. “I’m sorry about your father,” she tells him.

“I hope he feels better soon.” Then she rushes out the door, sure I’ll trail after her, even after everything.

Go, Jase mouths at me, lifting his chin toward the door. A look at those eyes and it’s clear; he has to know everything.

I hurry after my mom as her sandals click down the driveway. She stills, then turns slowly. It’s almost fully dark now, the streetlamp casting a shallow puddle of light on the driveway.

“Mom?” I search her face.

“Those children.”

“What about them?”

“I couldn’t stay any longer.” The words drag slowly out; then, in a rush. “Do you know Mr. Garrett’s room number? He’s at Maplewood Memorial, yes?”

Melodramatic scenarios crowd my mind. Clay will go there and put a pillow over Mr. Garrett’s face, an air bubble in his IV. Mom will…I no longer have any grasp of what she’ll do. Could she really come over and eat pizza and then do something terrible?

But she already has done something terrible, and then showed up with figurative lasagna. Here I am, your good neighbor. “Why?” I ask.

“I need to tell him what happened. What I did.” She compresses her lips, her gaze drawn back to the Garretts’ house, the light a perfect square in the screen door.

Oh thank God.

“Right now? You’re going to tell the truth?”

“Everything,” she replies in a small, soft voice. She reaches into her purse, taking out a pen and her tiny

“flag this” notebook. “What’s his room number?”

“He’s in the ICU, Mom.” My voice is sharp—how can she not remember? “You can’t talk to him. They won’t let you in. You’re not family.”

She looks at me, blinks. “I’m your mother. ”

I stare at her, completely confused, but then I realize. She thinks I meant she wasn’t my family. In the moment, it feels true. And I suddenly know I’m standing somewhere very far away from her. All my strength, all my will, is diverted into defending this family. My mom…What she’s done…I can’t defend her.

“They won’t let you into the room,” is all I say. “Only his immediate relatives.” Her face twists and, with a jerk of my stomach, I interpret her expression. Some shame. Mainly relief.

She won’t have to face him.

My eyes fall on the van, the driver’s-side door. I know who deserves the truth just as badly as Mr.

Garrett, though.

Mom’s hand moves convulsively to smooth the skirt of her dress.

“You need to talk to Mrs. Garrett,” I say. “Tell her. She’s home. You can do it now.” Again that snap of a gaze at the door, then a sharp turn of her head, as though the whole house is the scene of the accident. “I can’t go in there again.” Mom’s hand is rigid in mine as I pull at her, trying to urge her back up the driveway. Her palm is damp. “Not with all those children.”

“You have to.”

“I can’t.”

My eyes draw back to the door too, as though I’ll find the solution waiting there.

And I do. Jase, with Mrs. Garrett standing next to him. His shoulders are set, his arm tight around her.

The screen door opens and they come out.

“Senator Reed, I told my mom you had something to say.”

Mom nods, her throat working. Mrs. Garrett is barefoot, her hair sleep-rumpled, her face tired but composed. Jase can’t have told her.

“Yes, I—I need to speak with you,” Mom says. “In private. Would you—care to come have some lemonade at my house?” She dabs at her upper lip with one knuckle, adding, “It’s very humid tonight.”

“You can talk here.” Jase obviously doesn’t want his mother within range of Clay’s hypnotism. She raises her eyebrows at his tone.

“You’re more than welcome to come inside, Senator,” Mrs. Garrett’s own voice is soothing and polite.

“It will be just the two of us,” Mom assures Jase. “I’m sure my other company has left.”

“Right here will be fine,” he repeats. “Sam and I will keep the kids occupied inside.”

“Jase—” Mrs. Garrett begins, her cheeks flushing at her unaccountably rude child.

“That’s fine.” Mom takes a deep breath.

Jase opens the screen door, motioning me back in. I stand for a moment, looking from my mom to Mrs.

Garrett and back again. Everything about the two women profiled in the driveway is poles apart. Mom’s sunny yellow sheath, her pedicured feet, Mrs. Garrett’s rumpled sundress and unpolished toenails. Mom’s taller, Mrs. Garrett younger. But the pucker between each of their brows is nearly identical. The apprehension washing over their faces, equal.

Chapter Fifty-one

I don’t know how my mother said it, if the truth gushed or seeped from her lips. Neither Jase nor I could hear above the clatter of the kitchen, only see their silhouettes in the deepening darkness when we had a moment to steal a look as we cleaned up pizza boxes, shooed the kids into bath or bed or toward the hypnotic mumble of the television. What I know is that after about twenty minutes, Mrs. Garrett opened the screen door of the kitchen, her face giving nothing away. She told Alice and Joel she was headed to the hospital and needed them to come with her, then turned to Jase. “You’ll come too?” When they’ve gone, and Andy, obviously still suffering from the aftereffects of her Jake Gyllenhaal marathon, falls asleep on the couch, I hear a voice call from the back porch.

“Kid?”

I peer out the screen at the ember glow from Tim’s cigarette.

“Come on out. I don’t want to smoke indoors in case George wakes up, but I’m chaining, I can’t stop.” I step out, surprised by how fresh the air smells, the leaves of the trees shifting against the darkened sky. I feel as though I’ve been locked in stale rooms, unable to breathe, for hours, days, eons. Even at McGuire Park, I couldn’t take a deep breath, not with knowing what I had to say to Jase.

“Want one?” Tim asks. “You look like you’re gonna puke.” He offers me the crumpled pack of Marlboros.

I have to laugh. “I definitely would if I did. Too late for you to corrupt me, Tim.”

“Corrupt” comes back to slap me—the Garretts know now. Have they called the police? The press?

Where’s Mom?

“So.” Tim flicks the lighter open, crushing the previous butt under his flip-flops. “The truth is out there, huh?”

“I thought you’d gone home.”

“I booked it outside when you and Grace left. Thought Jase was going to spill it all, and it was a family time and all that shit.”

Yes, a nice little family gathering.

“But I didn’t want to go home in case, you know, somebody needed me for something. A ride, a punching bag, sexual favors.” I must make a face, because he bursts out laughing. “Alice, not you.

Babysitting, whatever. Any of my many talents.”

I’m touched. No Nan, but here is Tim. And after so much time away.

He seems to interpret my feelings, because he rushes to continue. “The sexual favor part is purely self-interest. Also, I fucking hate going to my house, so there’s that…Where’s Gracie?” Being read her rights?

My eyes fill. I hate this.

“Hell. Not this again. Stop it.” Tim waves his hand at my face frantically, as if he can shoo the emotions away like flies. “Did she go to the hospital to ’fess up?” I explain about the ICU. He whistles. “I forgot about that. Well, is she home?” When I tell him I have no idea, he drops the cigarette to the ground, mashes it, sets his hands on my shoulders, and turns me toward my own yard. “Go find out. I’ll man the fort here.” I walk down the Garretts’ driveway. Mom isn’t answering her cell. Maybe it’s been confiscated by the police who have already patted her down and fingerprinted her. It’s ten o’clock. The Garretts left here over an hour ago.

There are no lights on at our house. No sign of Mom’s car, but that could be in the garage. I climb the porch steps, planning to go through the side door and check for it, when I find her.

She’s sitting on the wrought iron bench by the front door, the one she bought to reinforce the fact that we should sit there and take our shoes or boots off outdoors. She’s wrapped her arms around her bent knees.

“Hi,” she says, in a quiet, listless voice. Reaching beside herself, she picks something up.

A glass of white wine.

Looking at it, I feel sick again. She’s sitting on the steps with chardonnay? Where’s Clay? Heating up the focaccia?

When I ask, she shrugs. “Oh, I imagine he’s halfway back to his summer house by now.” I remember her saying that if I told, she’d lose him too. Clay plays for the winning team. Mom takes another sip, swirls the glass, looking into it.

“So…did you guys…break up?”

She sighs. “Not in so many words.”

“What does that even mean?”

“He’s not very happy with me. Though he’s probably coming up with a good ‘resignation from the race’ speech. Clay does thrive on a challenge.”

“So…you kicked him out? Or he left? Or what?” I want to pull the glass out of her hand and toss it off the porch.

“I told him the Garretts deserved the truth. He said truth was a flexible thing. We had words. I said I was going over to talk to you. And the Garretts. He gave me an ultimatum. I left anyway. When I came back, he was gone. He did text me, though.” She reaches into the pocket of her dress, pulling out her phone as if it’s proof.

I can’t read the screen, but Mom continues anyway.

“Said he was still friends with all his old girlfriends.” She makes a face. “I think he meant ‘previous’

girlfriends, since I was probably the oldest. Said he didn’t believe in burning bridges. But it might be good if we ‘took a little time to reassess our position.’” Damn Clay. “So he’s not going to work with you anymore?”

“He has a friend on the Christopher campaign—Marcie—who says they could use his skills.” I bet. “But…but Ben Christopher’s a Democrat!”

“Well, yes,” Mom says. “I mentioned the same thing in my little text back. Clay just said, ‘It’s politics, sugar. It’s not personal.’” Her tone’s resigned.

“What changed?” I point at the bay windows of her office, curving gracefully out to the side of our house. “In there…you and Clay were on the same page.”

Mom licks her lips. “I don’t know, Samantha. I kept thinking of his speech about how I’d done it for you. To protect you and that Garrett boy.” She reaches out, sliding her palms down either side of my face, looking me in the eye, finally. “The thing is…you were the very last thing on my mind. When I thought of you…” She rubs the bridge of her nose. “All I thought was that if you hadn’t been there, no one would know.” Before I can respond or even let that sink in, she holds up a hand. “I know. You don’t have to say anything. What kind of mother thinks that? I’m not a good mother. That’s what I realized. Or a strong woman.”

My stomach hurts. Though I’ve thought this myself, though I’ve just recently said it aloud to Jase, I feel sad and guilty. “You told now, Mom. That’s strong. That’s good.” She shrugs, brushing off the sympathy. “When I first met Clay this spring, I stalled on mentioning I had teenagers. The truth was just…inconvenient. That I was in my forties with nearly grown daughters.” She gives a little rueful laugh. “That seemed like a big issue then.”