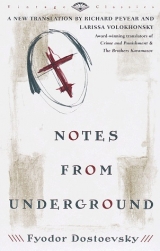

Текст книги "Notes from Underground"

Автор книги: Fyodor Dostoevsky

Соавторы: Fyodor Dostoevsky

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 10 страниц)

FYODOR DOSTOEVSKY

NOTES FROM UNDERGROUND

NOTES FROM UNDERGROUND

INTRODUCTION

LEV SHESTOV

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

CHRONOLOGY

1821

1823-31

1825

1831

1833-7

1834

1835

1836

1837

1839

1840

1841

1842

1843).

1845

1846

1847

1848

1849

1850

1851

1853-6

1855

1857

1859

1860

1861

1862.

1863

1864

1865

1865-9

1866

1867

1868

1869

1870

1871

1871-2

1872

1875

1875-8

1876

1878

1879

1880

1881

I*

II

III

IV

VI

VII

VIII

IX

X

XI

PART TWO

I

II

III

IV

VI

VII

VIII

IX

X

NOTES

18. "To domestic animals" (French).

FYODOR DOSTOEVSKY

Notes from Underground

Translated from the Russian by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volkhonsky with an Introduction by Richard Pevear

Copyright © 1993 by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky

ISBN: 1400041910

NOTES FROM UNDERGROUND

CONTENTS

Introduction – ix

Select Bibliography – xxiii

Chronology – xxvi

NOTES FROM UNDERGROUND

Part One Underground – 3

Part Two Apropos of the Wet Snow – 39

Notes – 121

INTRODUCTION

The ellipsis after the opening sentence of Notes from Underground is like a window affording us a first glimpse of one of the most remarkable characters in literature, one who has been placed among the bearers of modern consciousness alongside Don Quixote, Hamlet, and Faust. What we see is a man glancing at us out of the corner of his eye, very much aware of us as he speaks, very much concerned with the impression his words are making. In fact, we do not really see him, we only hear him, and not through anything so respectable as a window, but through a crack in the floorboards. He addresses the world from that crack; he has also spent a lifetime listening at it. Everything that can be said about him, and more particularly against him, he already knows; he has, as he says in a typical paradox, overheard it all, anticipated it all, invented it all. "I am a sick man… I am a wicked man." In the space of that pause Dostoevsky introduces the unifying idea of his tale: the instability, the perpetual "dialectic" of isolated consciousness. The nameless hero – nameless "because T is all of us," the critic Viktor Shklovsky suggested – is, like so many of Dostoevsky's heroes, a writer. Not a professional man of letters (none of Dostoevsky's "writers" is that), but one whom circumstances have led or forced to take up the pen, to try to fix something in words, for his own sake first of all, but also with an eye for some indeterminate others – readers, critics, judges, fellow creatures. He is a passionate amateur, a condition that marks the style and structure as well as the content of the book. Where the master practitioner would present us with a seamless and harmonious verbal construction, the man from underground, who literally cannot contain himself, breaks decorum all the time, interrupts himself, comments on his own intentions, defies his readers, polemicizes with other writers. The literariness of his "notes" and the unliterariness of his style are both results of his "heightened consciousness," his hostility to and dependence upon the words of others. Thus the unifying idea of Notes from Underground, embodied in the person of its narrator, is dramatized in the process of its writing. The controlling art of Dostoevsky remains at a second remove.

This man who may be trying to write his way out of the underground, originally read his way into it. "At home," he says, "I mainly used to read. I wished to stifle with external sensations all that was ceaselessly boiling up inside me. And among external sensations the only one possible for me was reading. Reading was, of course, a great help – it stirred, delighted, and tormented me." That was during his youth, in the 1840s. He read, he dreamed, and he engaged in "little debauches." These were his three diversions, and it is interesting that he puts them together. What did he read? At various points in his account he compares himself with Byron's Manfred, with characters from Pushkin and Lermontov – all romantic figures. He refers more than once to Rousseau. Farther in the background, but looming large, stand Kant and Schiller, representing German philosophical and poetic idealism, summoned up in the phrase "the beautiful and lofty," which had become a commonplace of Russian liberal criticism of the 1840s. His reading was, in other words, that of the typical educated Russian of the time. Reading nourished his dreaming, and even found its way into his little debauches "in exactly the proportion required for a good sauce." And so it was that he evaded the petty squalor and inner anguish of his daily life; so it was, as he confesses sixteen years later, that he "defaulted on his life through moral corruption in a corner." One main thematic strand of the book is the underground man's denunciation of the estranging and vitiating influence of books, so that from his perspective of the 1860s, when he begins to write, the word "literary" has become one of the most sarcastic he can utter. To all the features for an antihero purposely collected in Motes from Underground there are added all the features for an antibook.

That book is the underground man's book, not Dostoevsky's, though the two coincide almost word for word. Indeed, the sharp personality of the underground man, the intensity of his attacks and confessions, the apparent lack of critical distance in the first person narrative, have given many readers the impression that they have to do here with a direct statement of Dostoevsky's own ideological position, and much commentary has been written on the book in that light. Much has also been said about the tragic (or at least "terribly sad") essence of its vision. Both notions seem to overlook the humor

– stylistic, situational, polemical, parodic – that pervades Notes from Underground. Dostoevsky certainly put a lot of himself into the situations and emotions of his narrator; what distinguishes his book from the narrator's is an extra dimension of laughter. Laughter creates the distance that allows for recognition, without which the book might be a tract, a case history, a cry of despair, anything you like, but not a work of art. Notes from Underground has been called the prelude to the great novels of Dostoevsky's last period, and it is so partly because here Dostoevsky first perfected the method of tonal distancing that enabled him to present characters and events simultaneously from different points of view, to counter empathy with intellection.

The underground man's book is a personal outpouring

– harsh, self-accusatory, defiant, negligently written, loosely structured – a long diatribe, followed by some avowedly random recollections ("I will not introduce any order or system. Whatever I recall, I will write down.") It claims to be genuine, if artistically crude. "No longer literature, but corrective punishment," the narrator finally decides. Nietzsche thought he could hear "the voice of the blood" in it.

Dostoevsky's novel is something quite different. It is a tragicomedy of ideas, admirable for the dramatic expressiveness of its prose, which gives subtle life to this voice from under the floorboards with all its withholdings, second thoughts, loopholes, special pleadings; and admirable, too, for the dynamics of its composition, the interplay of its two parts, which represent two historical moments, two "climates of opinion," as well as two images of the man from underground, revealed by different means and with very different tonalities.

The two parts of Notes from Underground were first published in 1864, in the January and April issues of Epoch, a magazine edited by Dostoevsky's brother Mikhail, the successor to their magazine Time, which had been suppressed by the censors in

1863. The note Dostoevsky added to the first part insists on the social and typical, as opposed to personal and psychological, aspects of the man from underground: "such persons as the writer of such notes not only may but even must exist in our society, taking into consideration the circumstances under which our society has generally been formed." His view of those circumstances would have been familiar to readers of his articles in Time over the previous few years, particularly "Winter Notes on Summer Impressions," an account of his first trip to Europe in 1862, which had appeared in the February and March issues of Time for 1863. There he discussed Russia's "captivation" with the West:

Why, everything, unquestionably almost everything that we have -of development, science, art, civic-mindedness, humanity, everything, everything comes from there – from that same land of holy wonders! Why, our entire life, even from very childhood itself, has been set up along European lines.

Russian society had been formed by decades of imported "development" and "enlightenment," words that acquire a sharply ironic inflection in Dostoevsky's later work. Some sources of this ideology have already been mentioned – Rousseau, Schiller, Kant. To this list may be added the names of such French social romantics as Victor Hugo, Eugene Sue, George Sand, and the Utopian socialists Fourier and Saint-Simon. In Dostoevsky: The Stir of Liberation, Joseph Frank points to the presence of these "influences" in the theme of the redeemed prostitute, which was a favorite among Russian liberals of the 1840s (the poet Nikolai Nekrasov, for example), and which Dostoevsky parodies brilliantly in the second part of Notes from Underground. The parody is, of course, Dostoevsky's, not the underground man's. The latter, on the contrary, had taken all these influences to heart; they had made him into a "developed man of the nineteenth century," a man of "heightened consciousness." It was the attempt to live by them that drove him "underground." In the social displacement of an imported culture, Dostoevsky perceived a more profound human displacement, a spiritual void filled with foreign content.

A second theme from "Winter Notes" reappears in Motes from Underground – that of the "crystal palace," which is as central to the polemics of the novel's first part as the redeemed prostitute is to the parody of the second. The crystal palace in the travel article is the cast-iron and glass exhibition hall built in London in 1851 for the Great Exhibition. It appeared to Dostoevsky as a terrifying structure, a symbol of false unity, of "the full triumph of Baal, the ultimate organization of an anthill." The tones in which he speaks of it will be echoed almost twenty years later by the Grand Inquisitor in The Brothers Karamazov:

But if you saw how proud is that mighty spirit who created this colossal setting and how proudly convinced this spirit is of its victory and of its triumph, then you would shudder for its pride, obstinacy, and blindness, but you would shudder also for those over whom this proud spirit hovers and reigns.

This mighty spirit is the spirit of industrial capitalism, and the crystal palace is its temple. In Motes from Underground the same structure comes to stand for the future organization of socialism. It remains an image of false unity, but is denounced in rather different terms: the underground man puts his tongue out at it, calls it a tenement house and a chicken coop.

The two time periods of the novel represent two stages in the evolution of the Russian intelligentsia: the sentimental, literary 1840s and the rational and utilitarian 1860s; the time of the liberals and the time of the nihilists. One of Dostoevsky's constant preoccupations in his later work was the responsibility of the liberal generation for the emergence of the nihilists, an idea he embodied literally in the novel Demons (1871-72) in the figures of the dreamy individualist Stepan Verkhovensky and his deadly utilitarian son Pyotr. In Motes from Underground the same evolution is reflected in the mind of one man: the polemicist of the first part grew out of the defeated dreamer of the second. The inverted time sequence of the two parts seems to lead us to this discovery.

However, the underground man is hardly a typical "rational egoist," any more than he had been a typical romantic. There is a quality in him that sets him apart, which he himself defines on the last page of the book: "Excuse me, gentlemen, but I am not justifying myself with this allishness. As far as I myself am concerned, I have merely carried to an extreme in my life what you have not dared to carry even halfway." Submitted to the testing of full acceptance, the testing of this irreducible human existence, the "heightened consciousness" of the rationalist, like the sentimental impulses of the romantic, runs into disastrous and comic reversals. Hence the paradoxically defiant double-mindedness of the underground man, and his intransitive dilemma.

The "gentlemen" he addresses throughout his notes, when they are not a more indeterminate "you," are typical intellectuals of the 1860s. More specifically, they are presumed to be followers of the writer Nikolai Gavrilovich Chernyshevsky, the chief spokesman and ideologist of the young radicals. N. G. Chernyshevsky was the author of a number of critical works, notably The Anthropological Principle in Philosophy (1860), in which he propounded the abovementioned doctrine of "rational egoism," an adaptation of the "enlightened self-interest" of the English utilitarians. His programmatic Utopian novel What Is to Be Done?, written in prison following his arrest in 1862 for revolutionary activities and published in 1863, immediately became a manual for social activists. Several decades later, V. I. Lenin, who dubbed Dostoevsky a "superlatively bad" writer, could testify that What Is to Be Done? had made him into a confirmed revolutionary. The nature of Chernyshevsky's hero and his ideas may be deduced from the following passage:

Yes, I will always do what I want. I will never sacrifice anything, not even a whim, for the sake of something I do not desire. What I want, with all my heart, is to make people happy. In this lies my happiness. Mine! Can you hear that, you, in your underground hole?

This is the voice of the healthy rational egoist, the ingenuous man of action. Dostoevsky took up the challenge.

Though Chernyshevsky is not mentioned by name in Motes from Underground, his theories, and in particular his novel, are the most immediate targets both of the underground man's diatribes and of Dostoevsky's subtler, more penetrating parody. Dostoevsky had intended originally to write a critical review of What Is to Be Done? for the first issue of Epoch, but was unable to produce anything. The strained conditions of his personal life at that time and the problems of starting the new magazine do not explain the difficulty he faced. Evidently it was not enough for him simply to counter Chernyshevsky's arguments; more was at stake than a conflict of ideas – there was a question of the very nature of the human being who was to be so forcibly made happy. Dostoevsky's response had to take artistic form. He was challenged to reveal "the man in man," precisely in and through the ideas of the new radicals themselves.

The counterarguments of the "gentlemen" in the later chapters of the first part, for example, are clearly Cherny-shevskian, based on his notions of normal interests, natural law, and the denial of free will. The crystal palace, too, in its reappearance here, has been transmuted by its passage through "The Fourth Dream of Vera Pavlovna," the section of What Is to Be Done? that presents Chernyshevsky's vision of mankind made happy. The pseudoscientific terms and even a certain clumsy use of parentheses, as Joseph Frank has shown, are the narrator's deliberate mockery of Chernyshevsky's writing. Frank has also shown that the attack is not limited to Part One: two of the three main episodes in the second part of Notes – the episode of the bumped officer and the episode with the prostitute Liza – are in fact parodic developments of episodes from Chernyshevsky's novel. The latter episode, which is the climactic episode of the novel as a whole, gives fullest play to Dostoevsky's criticism through comic reversal. But the reversal is not a simple contrary; it is the puncturing of a literary cliche by a truth drawn from a different source, from what the narrator comes in the end to call "living life."

Dostoevsky's reply to Chernyshevsky is both ideological and artistic, the implication being that the two are inseparable, and the further implication being that the indispensable unity of artistic form reflects a more primordial unity of the living person. Those who favored Chernyshevsky's ideas, however, were able to separate them from the form of their expression. Even the conscientious old radical Alexander Herzen, though he found Chernyshevsky's novel "vilely written" and could not help noting that it ends with "a phalanstery in a brothel," immediately added: "On the other hand there is much that is good and healthy." (An interesting pair of adjectives when one recalls the opening lines of Motes.) These remarks of Herzen's are passed on to us by Fyodor Godunov-Cherdyntsev, the narrator of Vladimir Nabokov's The Gift (1938), whose monograph on the life of Chernyshevsky makes up the fourth of the novel's five chapters. Godunov-Cherdyntsev notes a certain "fatal inner contradiction" in Chernyshevsky's own reflections on art, what he describes as the dualism of the monist Chernyshevsky's aesthetics – where "form" and "content" are distinct, with "content" pre-eminent – or, more exactly, with "form" playing the role of the soul and "content" the role of the body; and the muddle is augmented by the fact that this "soul" consists of mechanical components, since Chernyshevsky believed that the value of a work was not a qualitative but a quantitative concept, and that "if someone were to take some miserable, forgotten novel and carefully cull all its flashes of observation, he would collect a fair number of sentences that would not differ in worth from those constituting the pages of works we admire."

Indeed, there could hardly be a more thorough denial of artistic unity than this last quoted passage. The naive blithe-ness of its expression is characteristic of Chernyshevsky and thinkers like him (utilitarians, nihilists; then Lenin, Lunachar-sky, the theorists of "socialist realism"). It is defined by Nabokov's narrator in terms of a decomposition of the human person. The metaphor comes quite naturally; the aesthetic question immediately brings with it the human question – or, rather, they are the same.

As a writer and thinker, Chernyshevsky was the embodiment of what in Russian is called bezdarnost' – giftlessness – and was thus the perfect foil for that minutely observant, wondering, grateful, and form-revealing intelligence that Nabokov celebrates in The Gift. Giftlessness, as Dostoevsky feared and Nabokov knew, became the dominant style in Russia; it eventually seized power, and in the process of "making people happy" destroyed them by millions, leaving its vast motherland broken and desolate. "The triumph of materialism has abolished matter," the poet Andrei Bely said in the famine– ridden 1920s. Godunov-Cherdyntsev gives a more detailed formulation:

Our overall impression is that materialists of this type fell into a fatal error: neglecting the nature of the thing itself, they kept applying their most materialistic method merely to the relations between objects, to the void between objects and not to the objects themselves; i.e. they were the naivest metaphysicians precisely at that point where they most wanted to be standing on the ground.

A fatal error, a fatal contradiction. In this respect the greatest foresight was shown by long-eared Shigalyov, the radical theoretician in Dostoevsky's Demons: "I got entangled in my own data, and my conclusion directly contradicts the original idea I start from. Starting from unlimited freedom, I conclude with unlimited despotism. I will add, however, that apart from my solution to the social formula, there is no other." A direct line leads from metaphysical naivety to murder; a direct line leads from the anti-unity of utilitarian aesthetics to the false unity of the crystal palace. Dostoevsky perceived these relations more clearly than anyone else of his time. The perception coincided with, and in fact constituted, the maturity of his genius. He recognized that his opposition to the "Chernyshev-skians" could not be a struggle for domination, that what was in question was the complex reality of the human being, the whole person, the "thing itself," and that a true articulation of that reality could only come as the final "gift" of an artistic image. Mikhail Bakhtin noted in his study of Dostoevsky's poetics: "Artistic form, correctly understood, does not shape already prepared and found content, but rather permits content to be found and seen for the first time."

Hence the formal inventiveness of Notes from Underground: its striking language, unlike any literary prose ever written; its multiple and conflicting tonalities; the oddity of its reversed structure, which seems random but all at once reveals its deeper coherence – "chatter… resolved by an unexpected catastrophe," as Dostoevsky described it to his brother. ("All Dostoevsky's novels were written for the sake of the catastrophe," the critic Konstantin Mochulsky observed. "This is the law of the new 'expressive art' that he created. Only upon arriving at the finale do we understand the composition's perfection and the inexhaustible depth of its design.") The catastrophe that resolves Notes from Underground, with its resoundingly symbolic slamming door, is at the same time the moment of its origin. There, in a sudden confusion of tenses, the narrator cries out from the past into the future: "and never, never will I recall this moment with indifference." It is a fleeting moment, but it has determined the narrator's life and gives the edge of passion to his attack, his outburst, after all his years "underground." Coming at the end of the book, it sends us back to the beginning; thus the round of the underground man's ruminations is given form, and this whole "image" Dostoevsky holds up to us as a sign.

There may, however, have been a more directly opposing idea in the book as Dostoevsky originally wrote it, a sort of ideological climax in Part One to match the narrative climax in Part Two. When the first part appeared in Epoch, Dostoevsky complained in a letter to his brother that the tenth chapter -"the most important one, where the essential thought is expressed" – had been drastically cut by the censors. "Where I mocked at everything and sometimes blasphemed for form's sake – that is let pass; but where from all this I deduced the need of faith and Christ – that is suppressed."

The published version of the chapter, according to its author, was left "full of self-contradictions." Indeed, the reader will notice that in the third paragraph the "crystal edifice" ceases all at once to represent the ideas of the narrator's opponents and becomes instead something that he himself has possibly invented "as a result of certain old nonrational habits of our generation," something, he says, that "exists in my desires, or, better, exists as long as my desires exist." Obviously there have been major cuts here, removing the transition from one crystal edifice to the other – the word "mansion" being left us as a clue to its nature. We must try to imagine what would have transformed the "chicken coop" into a mansion, what would have made it more than "a phalanstery in a brothel," what would have turned it from an embodiment of the "laws of nature" into a contradiction of those very laws, and how from all this "the need of faith and Christ" was deduced. Dostoevsky never restored the cuts, as he never restored similarly drastic cuts in Crime and Punishment and Demons. Various explanations have been offered for this circumstance, some practical (lack of time, reluctance to confront the censors), others aesthetic (a recognition that the cuts were improvements). We do not know. But if we look at Dostoevsky's outlines of his ideas for novels in his notebooks and letters and then at the novels themselves, we will realize at least that the scheme barely hints at the surprises of its development. However it was that Dostoevsky "deduced the need for faith and Christ" in this chapter, we may be sure that he did not add it on as an external "ideological" precept, but drew it from the materials of the work itself.

The man from underground refutes his opponents with the results of having carried their own ideas to an extreme in his life. These results are himself. This self, however, as the reader discovers at once, is not a monolithic personality, but an inner plurality in constant motion. The plurality of the person, without any ideological additions, is already a refutation of l'homme de la nature et de la verite, the healthy, undivided man of action who was both the instrument and the object of radical social theory. Unity is not singularity but wholeness, a holding together, a harmony, all of which imply plurality. What the principle of this harmony is, the underground man cannot say; he has never found it. But he knows he has not found it; he knows, because his inner disharmony, his dividedness, which is the source of his suffering, is also the source of consciousness. Here we come upon one of the deep springs of Dostoevsky's later work – not his thinking (Dostoevsky was not a thinker, or, rather, he was a plurality of thinkers), but his artistic embodiment of reality. The one quality his negative characters share, and almost the only negative his world view allows, is inner fixity, a sort of death-in-life, which can take many forms and tonalities, from the broadly comic to the tragic, from the mechanical to the corpselike, from Pyotr Petrovich Luzhin to Nikolai Stavrogin. Inner movement, on the other hand, is always a condition of spiritual good, though it may also be a source of suffering, division, disharmony, in this life. What moves may always rise. Dostoevsky never portrays the completion of this movement; it extends beyond the end of the given book. We see it in characters like Raskolnikov and Mitya Karamazov, but first of all in the man from underground.

*

How much the mere tone of Notes from Underground is worth!

LEV SHESTOV

The philosopher Shestov, the critic Mochulsky, and most Russian readers agree that the style of Notes from Underground is, in Shestov's words, "very strange." Bakhtin describes it as "deliberately clumsy," though "subject to a certain artistic logic." A detailed discussion of the matter is not possible here, but we can offer a few comments on the style of our translation, pointing to qualities in the original that we have sought to keep in English for the sake of "mere tone," where they have been lost in earlier translations.

Though he likes to philosophize, the underground man has no use for philosophical terminology. When he picks up such words, it is to make fun of them; otherwise he couches his thought in the most blunt and even crude terms. An example is his use of the rare word khoteniye, a verbal noun formed from khotet', "to want." It is a simple, elemental word, with an almost physical, appetitive immediacy. The English equivalent is "wanting," which is how we have translated it. The primitive quality of the word appears to have alarmed our predecessors, who translate it as "wishing," "desire," "will," "intention," "choice," "volition," and render it variously at various times. The underground man invariably says "wanting" and "to want." He plays on the different uses of the word ("Who wants to want according to a little table?"); there is one passage running from the end of Chapter VII to the start of Chapter VIII in the first part where "want" and "wanting" appear eighteen times in two paragraphs – the stylistic point of which is blunted when other words are used.

Another of the underground man's words is vygoda, which means "profit" (gain, benefit), and only secondarily "advan– tage," as it is most often translated. "Profit" has very nearly the same range of uses in English as vygoda has in Russian. It is also a direct, unambiguous word, with an almost tactile quality: you have an advantage, but you get a profit. And like vygoda, with its strongly accented first syllable, "profit" leaps from the mouth almost with the force of an expletive, quite unlike the more unctuous "advantage" or its Russian equivalent preimushchestvo. Again, the narrator insists on his word and plays with it. Thus we arrive at the full music of this underground oratorio:

And where did all these sages get the idea that man needs some normal, some virtuous wanting? What made them necessarily imagine that what man needs is necessarily a reasonably profitable wanting? Man needs only independent wanting, whatever this independence may cost and wherever it may lead.

Repetition is of the essence here. When the underground man speaks of consciousness and heightened consciousness, it is always the same word: "consciousness," not "intellectual activity" as one translator has it, not "awareness" as another offers, and never some mixture of the three. The editorial precept of avoiding repetitions, of gracefully varying one's vocabulary, cannot be applied to this writer. His writing is emphatic, heavy-handed, rude: "This is my wanting, this is my desire. You will scrape it out of me only when you change my desires." To translate the scullery verb v yskoblit' ("to scrape out") as "eradicate" or "expunge," as has been done, to exchange the "collar of lard" the narrator bestows on the wretched clerk in Part Two for one that is merely "greasy," is to chasten and thus distort the voice of this man who is nothing but a voice.

There is, however, one tradition of mistranslation attached to Motes from Underground that raises something more than a question of "mere tone." The second sentence of the book, Ya zloy chelovek, has most often been rendered as "I am a spiteful man." Zloy is indeed at the root of the Russian word for "spiteful" (zlobnyi), but it is a much broader and deeper word, meaning "wicked," "bad," "evil." The wicked witch in Russian folktales is zlaya ved'ma (zlaya being the feminine of zloy). The opposite of zloy is dobryi, "good," as in "good fairy" (dobraya feya). This opposition is of great importance for Notes from Underground; indeed it frames the book, from "I am a wicked man" at the start to the outburst close to the end: "They won't let me… I can't be… good!" We can talk forever about the inevitable loss of nuances in translating from Russian into English (or from any language into any other), but the translation of zloy as "spiteful" instead of "wicked" is not inevitable, nor is it a matter of nuance. It speaks for that habit of substituting the psychological for the moral, of interpreting a spiritual condition as a kind of behavior, which has so bedeviled our century, not least in its efforts to understand Dostoevsky. Besides, "wicked" has the lucky gift of picking up the internal rhyme in the first two sentences of the original.